by

Arthur Chandler

Reproduced from World's Fair magazine, Volume VI, Number 2, Copyright 1986, World's Fair, Inc.

Expanded and revised versions 2000 and 2014 by Arthur Chandler

For the story of the national expositions that preceded the 1855 universal exposition, follow these links:

The First Exposition, 1798

The Napoleonic Expositions: 1801, 1802, 1806

Expositions of the Restoration: 1819, 1823, 1827

Expositions of the July Monarchy: 1834, 1839, 1844

Exposition of the Second Republic: 1849

THE SHADOW OF NAPOLÉON

Exactly ten years before the opening of the first universal exposition in Paris, the future father of the event was serving a lifetime prison term in the state military fortress at Ham. Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, nephew and adopted godson of the Emperor, had failed in his second attempt at a coup d'état against the restored monarchy of Louis Philippe. After the first attempt in 1836, the government had exiled him to America. The second attempt in 1840 earned him the detention term at Ham, behind the very walls that, over four centuries before, had held Joan of Arc captive. Many monarchists and conservatives in the Court of Peers and the National Assembly wished for terminal punishment; but the name of Napoléon was in the ascendant once again throughout France. On the very day when Charles Louis was sentenced, Emperor Napoléon's ashes were received by both royalty and the multitudes of Paris with great pomp at the church of Les Invalides. And so, rather than arouse the wrath of the still considerable number of Bonapartists, the Court of Peers determined to make the military fortress at Ham the Elba of Charles Louis.

Charles Louis Bonaparte at "The University of Ham"

It was not a harsh captivity. At this "University of Ham," as he called it, Charles Louis dreamed his dreams of empire. He passed the time writing fragments of history, proposing schemes for cutting a canal through Nicaragua, and publishing a series of articles on the abolition of pauperism. Intellectual friends, both men and women, lightened his captivity with frequent visits. He also found time to correspond with the radical political philosopher Pierre Proudhon, the flamboyant bohemian writer George Sand, and other fellow spirits. But the fortress at Ham could not restrain a man who proposed ocean-splicing canals and the eradication of poverty. Disguised as a workman, he escaped to London in 1846.

In England, the escaped pretender cut a strange figure in society. He was handsome, and the blood of the Bonapartes flowed in his veins. He had many friends and mistresses, spent their money freely on his pleasures. But he always insisted that it was his destiny to become his uncle's successor, to restore France to her former glory. Even his friends smiled with pity. Let the man dream.

But in the ensuing years, as Charles Louis's star climbed toward its zenith, his faith in his own destiny seemed justified. The restored monarchy committed blunder after political blunder in its attempt to win English favor and avoid conflicts on foreign soil. The National Assembly performed no better, losing widespread support by opposing universal suffrage. In spite of a decree banning the Bonaparte family from France forever, Charles was elected in absentia to the Assembly. He skillfully parlayed his popularity, and the halo of glory around the name Napoléon, into the presidency of the National Assembly in 1848.

President Charles Louis Bonaparte, 1848

After a parliamentary struggle with the retreating forces — supporters of the monarchy and revolutionaries who wished France to become a republic — Charles Louis took command of the army and forcibly dismissed the assembly. He was proclaimed Emperor of the French on December 1, 1851.

Napoléon III had won his throne through force of will and wiles. From the time of his youth, in exile and disgrace as a bearer of the Bonaparte name, he never doubted that he was destined for greatness. Now his time had come, and the crown was his alone. But to hold it, to give his reign legitimacy and security, he needed to demonstrate to the French people, and to the allies and enemies of France, that, in addition to the blood of the Bonapartes, he had the spirit of a true Napoléon. To this end, Napoléon III set about persuading the world of his worth with a series of dramatic gestures: marriage to a beautiful and certified aristocrat, a convincing military victory abroad, a grand plan for redesigning the very face of Paris, and a universal exposition.

AT HOME AND ABROAD

His first goal was achieved in January of 1853, when he married Eugénie de Montijo, Comtesse de Teba. His earlier marriage offers to the houses of Vasa and Hohenzollern had been rejected contemptuously. The marriage to Eugénie was a personal triumph for the new Emperor, who had yet to prove his legitimacy to the crowned heads of Europe. Through their children, Napoléon III hoped to establish the new bloodline for French royalty. Eugénie's beauty and charm made her one of the bright lights of his reign, and her strength of character sustained — some would say overwhelmed — him through the triumphant years of his reign and the final, bitter years of his exile.

The remaking of Paris began, by Napoléon III's decree, in 1855, when Baron Haussman began cutting his swath through slums and churches in order to give the Paris of the new empire the Roman grandeur of wide boulevards and focal points of monumental structures. Beneath the streets, there were new sewers and water pipes; over the water, new bridges. Even more decisively than his famous uncle, Napoléon III would leave his stamp on the very shape and infrastructure of Paris.

Napoléon III's opportunity for military glory presented itself when the French joined with the British in opposing Russia's claims in the Crimea. Here was a perfect chance for France to re-establish her reputation as a first-rank military power — a reputation that had been a shambles since Waterloo. The successes of the French army and navy in the Crimea — at Fedukhin Heights, Mamelon, and Malakoff — coincided with the exposition universelle, and lent an aura of triumph to the spirit of the whole enterprise.

On the issue of war and peace, there appeared to be a flat contradiction between the stated theme of the fair and the actions of Napoléon III. In his inaugural speech for the universal exposition at the Palace of Industry the Emperor proclaimed: "With great happiness I hereby open this temple of peace that brings together all peoples in a spirit of concord."(1) At that very moment, far away in the Crimean campaign, French, English, Turkish, Italian and Russian troops were engaged in a ferocious struggle over Russia's right to rule the Crimea.

In the minds of most citizens of the Second Empire, there was no contradiction. Peace meant peace at home. No one seriously questioned the right of any nation to keep itself strong and respected by military engagements whenever the situation warranted intervention. What was unusual was for a nation to be both warlike and benign at the same moment. Prince Napoléon summed up this achievement with a boast: "Never before has a people been privileged to be, at the same moment, great in peace and powerful in war."(2) The message to the French people was crystal clear: Napoléon III incarnates both the military might of Julius Caesar's rule, and the peaceful arts of the reign of Augustus.

It is possible that the audience at the inaugural speech thought that the Napoléon had other motives for stressing the necessity of peace at home. In the early hours of that very morning on the inaugural day of the exposition, a prisoner named Pianori was guillotined for attempting to assassinate the Emperor.

THE EMPEROR'S EXPOSITION

Napoléon III had entrusted the redesign of Paris to a talented aristocrat, and the fate of his troops to the experienced General Pélessier. But for the success of the first Paris international exposition, he turned to a close member of his own family, his cousin Prince Napoléon. The Emperor superseded the original plans for a national industrial exposition and the annual fine arts salon, both to be held in 1854, with an ambitious design for an international exposition in 1855. It was of utmost importance that this exposition compare favorably with the English Exhibition of 1851; yet the British, allies of the French for the first time in the history of either nation, were not to be antagonized by gratuitous shows of patriotism or rivalry. Prince Napoléon was named President of the Exposition with those two goals clearly before him.

When, in 1851, England shows the advantages of including exhibits from other nations, the lesson was not lost on the French. Indeed, many Parisian intellectuals felt incensed that the British had succeeded in launching the first international exposition. "The brazen imitator England has stolen from us the idea of a universal exposition."(3)

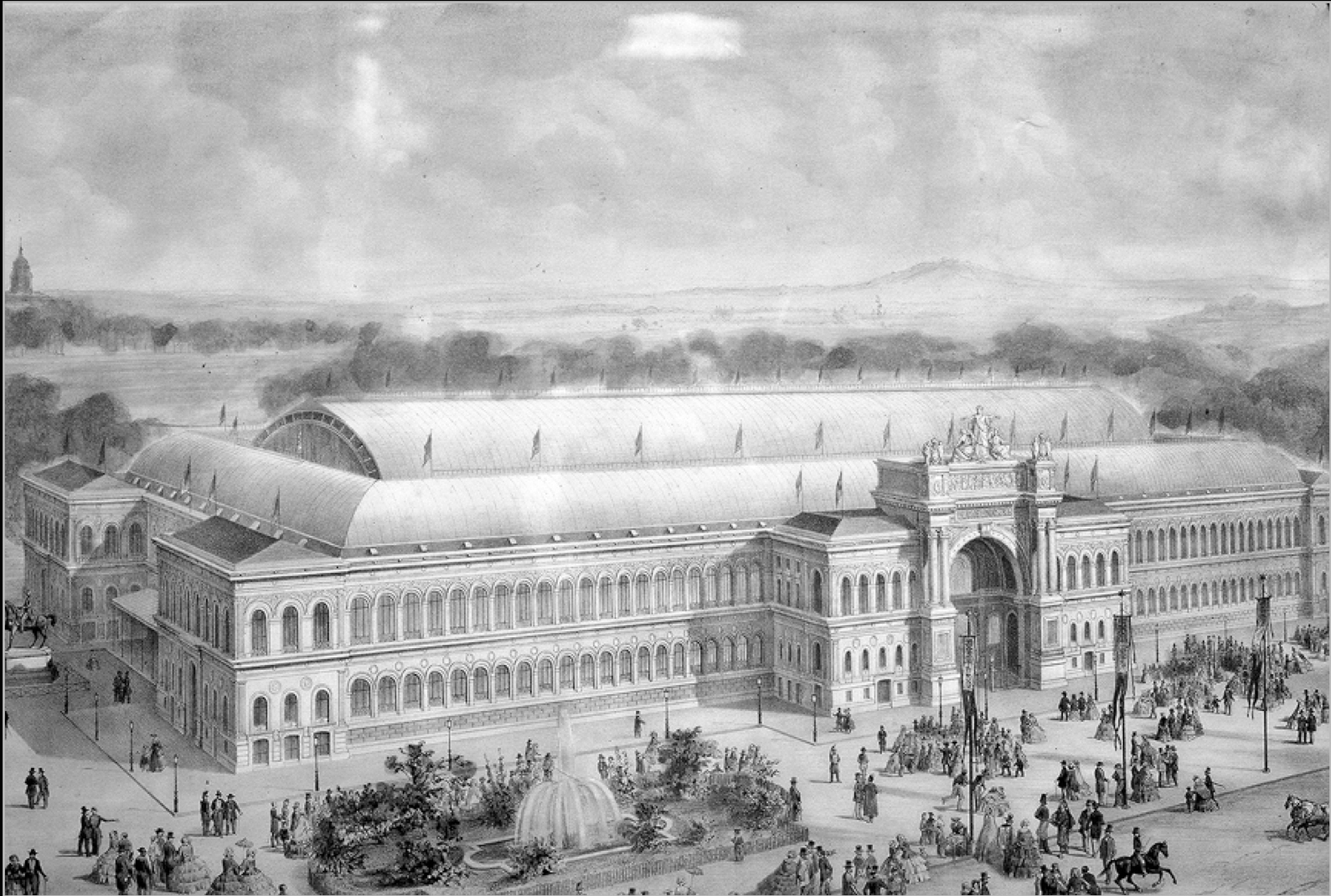

Though it was too late for France to be first, it was not too late to match or better the efforts of England. Prince Napoleon stated the matter succinctly to the Emperor: "Universal expositions are a necessity of our time."(4) A site along the Champs-Elysées was chosen for the main exhibition hall, the Palais d'Industrie, designed and built through the collaboration of architect Jean-Marie Viel and engineer Alexandre Barrault. On the Avenue Montaigne, Hector Fuel’s Palace des Beaux Arts would house the painting, sculpture, engraving and lithography. Because the main Palace of Industry was, despite its immense proportions, too small to house all the machinery exhibits, a third gallery was built along the banks of the Seine. In all, the exposition site covered 34 acres in the very heart of the city. By 1855, Paris was prepared to play host to the world — and especially to France's new allies and old rivals, the English.

Main 1855 Exposition Hall designed by Jean-Marie Viel and Alexandre Barrault

Fine Arts Building by Hector Fuel

QUEEN VICTORIA CONQUERS PARIS

As early as 1798, French financiers knew that, in questions of manufacturing and marketing, England was the nation to beat. An invitation to exhibitors in that year especially invited products which could be compared favorably with similar products of British industry. And though the French national exhibitions had grown steadily in size, importance, and prestige since that time, England seized the leadership once again by launching its successful international exhibition in 1851.

There was another agenda for the French nation in 1855: to erase the memories of the Napoleonic wars of the First Empire. Many French people were still violently antagonistic towards the English, and many Englishmen reciprocated the feelings. Emperor Napoléon himself, though, had virtually grown up in England, and found much to admire in the culture and values of his home in exile. The offer he extended to the British, therefore, was a compound of genuine affection and ancient French-English rivalry. But questions remained. If the English sent an official envoy, they would in effect be acknowledging the legitimacy of Napoleon’s regime. Would the British Empire make any steps towards reconciliation with France and official acknowledgment of the Second Empire?

No less a personage than Queen Victoria herself made the necessary first advance. The Queen's visit to the 1855 exposition was warmly received by the supporters of the Second Empire as a gesture of official recognition, by the reigning monarch of England, that Napoléon III was the legitimate Emperor of the French. It was a novel experience for the French people, for so many centuries at odds with the English, to hear the organ at Les Invalides thundering out the strains of God Save the Queen and to listen to their military band give a rousing rendition of Rule, Britannia. But, following the lead of their emperor, the French people threw themselves enthusiastically into the spirit of the occasion. Wherever she went, Victoria was greeted with thunderous applause.

The Queen of England visited the Palais des Beaux Arts on August 20, and the Palais d'Industrie on the 22nd. Such a huge crowd had accompanied the monarch to the fine arts exhibit that the Exposition authorities ruled that only season ticket holders could come on the day the Queen would visit the Palais d’Industrie. The result: in one day, over a thousand season tickets were sold. The audience was treated to a special ceremony in the Palais, where the Emperor presented Prince Albert with a magnificent Sèvres vase commemorating the London Exposition of 1851.

Sèvres Commemorative Vase, designed by Jean-Lèon Gérôme

The next day, when the Queen returned to her rooms in the Tulieries Palace, she found a special present from the Emperor. As they had toured the Palais d'Industrie, Napoléon quietly noted every exhibit that especially pleased Victoria. He then dispatched his agents to purchase the items, and delivered them all to her room. The English Queen had conquered Paris.(5) Victoria's presence marked the first time that a reigning British monarch had visited the French capitol since Henry VI's coronation in 1431. The reception of the Queen and Prince Albert at the Exposition, where British and French exhibits competed peacefully side by side, was taken by both nations as an explicit and official message that the ancient military rivalry between France and England had come to an end.

Emperor Napoleon III and Queen Victoria visit the Fine Arts Building at the 1855 Exposition

Lords of the World

At least one writer saw, in the visit of the queen of England to the French exposition, more than a mere political alliance. Critic Jean-Jacques Arnoux in his review of the exposition universelle, rose to ecstasy as he contemplated the symbolism of the event:

It is your lot, O Queen, to bring civilization to India! Your task, O Emperor, to civilize Africa! The peaceful world will not trouble our glorious labor so long as we stand united.(6)

The 1855 exposition marks the first major public display of products from the colonial empires of the world. England grouped her possessions — Ceylon, Jamaica, British Guyana, Malta, Tasmania, the Bahamas, and of course her crown jewel, India — in the gallery annex. The French proudly matched the British with substantial displays of products from the Antilles, Senegal, the island of Réunion, Madagascar, Gabon, and especially the newly-won Algeria. Of the 911 total exhibits from French colonies, 728 were from Algeria alone. The Algerian section featured exhibits of cereals, wines, tobacco, rare woods, musical instruments, and toys. "This exhibition," said Frederic Lacroix, "is worth more than ten years worth of essays and a big collection of articles in Le Moniteur. It is a palpable, material demonstration of the prodigious fecundity of Africa."(7)

The colonial section of the exposition is the first in a long series of such displays which will culminate in the exposition coloniale of 1931. Only later will we find the sentiment that all the colonies are members of the great family of France Outre-Mer. In 1855, the French attitude is a mixture of pure greed and the dawning sense of the "civilizing mission" of France: Africa will supply the raw materials; and in return, France will supply the most precious of all commodities: French civilization.

Colonial Section of the 1855 Exposition

The colonial section was linked, as the above-cited passage by Arnoux makes clear, to France’s desire to keep up with the English — to at least share, if not to dominate, the leadership of the entire world.(8) But the Emperor's task involved much more than simply keeping the English at friendly bay. There were a number of issues that Napoléon III's rise to the throne had left unresolved. He had routed the National Assembly over the question of universal suffrage. They had wanted to restrict it; citizen Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte argued forcibly for its extension. He had won his case for the people, and now he was emperor. It was the task of the new ruler to reconcile the rights of populism with the privileges of royalty.

And finally, there was the issue of French pride. After the humiliating defeat at Waterloo 40 years before, France had been torn with internal strife. The Emperor himself had been involved in two unsuccessful rebellions — and these were but minor instances among many such that clearly bespoke a loss of direction in French civilization. With the decline of governmental stability and military prowess, Paris might well cease to be a major center of European art and thought. It seemed conceivable that France, so long a dominant force in European civilization, might produce no more giants of the caliber of Descartes, Voltaire, Poussin, Rameau. The 1851 exposition in London proved to the whole world that England had become the leading industrial power of Europe. Was England now the foremost nation in the world?

To regain self-respect and the esteem of her enemies and allies: these were two of the unspoken but universally recognized goals of the first French exposition universelle.

"THE GREATEST GOOD FOR THE GREATEST NUMBER"

The exposition embodied a number of seeming paradoxes. An emperor had brought about France's first world's fair; but its stated ideals were, in many respects, democratic. Some of this incongruous blend of despotism and humanitarian ideals was the legacy of Napoléon I. But Emperor Napoléon III was also a man of liberal social convictions, and at least a partial disciple of Saint-Simon.

In his final Rapport sur l"Exposition Universelle de 1855, Prince Napoléon explicitly espoused the Utilitarian populism of Jeremy Bentham and Saint Simon. Not just the present exposition, but all future ones should, in the Prince's phrase, be dedicated to the principle of plus d'aisance au profit du plus grand nombre (9) — "the greatest good for the greatest number." Exhibits at the fair showed more than huge machines and expensive goods for wealthy buyers. There were exhibits that expressly catered to thinner purses, espousing the worth of the new idea of bon marché ("bargain goods"). Cheap goods were shown at the 1855 exposition, not simply as an attempt to exploit a new market. The bon marché displays expressed the Emperor's belief that poor, middle class, and rich alike would benefit from the industrial revolution. The huge and intricate machines on display at the Palais d'Industrie could produce inexpensive clothes and kitchen utensils as well as cannonballs and railway gears.

Prince Napoléon instituted another innovation at the 1855 exposition: price tags. Every item on display at the Palace of Industry was marked with a price, and all items could be purchased or ordered on the spot. The 1855 Exposition thereby had much more of a marketplace atmosphere than its English predecessor. In this respect, the first French international exhibition, though financed by the French government, hearkens back in spirit to the centuries-old trade fairs that flourished in the countryside, and under the aegis of Saint Denis in Paris.

The exposition committee, under Prince Napoléon's leadership, took practical measures to encourage universal attendance at the exhibition — the exact counterpart to the Emperor's longstanding support of universal suffrage. The original entrance price was lowered to two francs when it was observed that many Parisians could not afford the original five-franc fee. Special trains were chartered for the sake of provincial fair-goers. Tour groups were organized to explain the wonders of the fair to the uninitiated. Guidebooks and picture albums provided assistance for the judgement and memory of people overwhelmed with the variety and range of the exhibits. The 1855 exposition was "universal," not only in the sense of including all civilized cultures of the world, but also in the sense of applied democracy.

In this effort, the exposition was only partly successful. The "common folk" did not come in great numbers. All in all, the exposition was a stage for the wealthy, the intellectuals, and the artists. Prince Napoleon's discouragement is evident in his final report, where he urges that future expositions should beware of trying to outshine their predecessors by attracting huge, indiscriminate crowds and displaying more, but less worthy, exhibits. He concluded that in the future such events be directed primarily toward those who could comprehend the significance of what universal expositions were attempting to accomplish.

Though some critics, like Ernest Renan, feared that the French government had gone too far in pandering to common tastes, the overwhelming majority of exhibits in the Palace of Industry were quite conservative in their form and function. The luxury industries dominated the central hall: elaborately chased silver dinner services, scintillating chandeliers, Sèvres urns — all ornamented in decorative styles that drew from the eras of "classical Greece, the Renaissance, Gothic, Roman, Arabic culture, the reigns of Louis XIII, Louis XIV, Louis XV and Louis XIV — a veritable confusion of antagonistic sources producing the most divergent of effects,"(10) according to one writer.

Taken all together, the French exhibits did not surpass the British exhibits of the Crystal Palace. But victory was not the goal. The French government and the individual exhibitors wanted to show that they could compete on a par with the British, and that French ingenuity was not qualitatively inferior to that of any other nation. If a London craftsman could produce a hunting knife with 80 blades, then a Parisian inventor could make a 10 foot high percolator that brewed 2,000 cups of coffee an hour.

And in one area, at least, French superiority was incontestable: the fine arts.

THE GOLDEN THRONE

Because of the longstanding antipathy between the fine arts and industry — the "beaux-arts" and the "arts utile" — the two groups never exhibited together in any of the national industrial expositions between 1801 and 1849.(11) The English exhibition of 1851 achieved a partial rapprochement by allowing for a section of the exhibit to be devoted the sculpture — presumably because of technical processes of working with marble and bronze bore some resemblance to industrial techniques. But the Britons specifically excluded painting for the somewhat obscure reason that this art "was but little effected by material conditions."(12) The French press, already miffed that the English had stolen a march on France by hosting the first international exhibition, excoriated the English as "Philistines" for this exclusion.(13) To make matters worse, British jurors were openly shocked by what they deemed to be indecent works by French sculptor Jean-Baptiste Clésinger, and refused to honor their previous commitment to award him a bronze medal for his Bacchante.

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view of the Bacchante))

Still and all, when the final tally was taken, French artists had one more prizes than any other nation. The message to Napoleon III was clear. Since the fine arts were the one case where even the British acknowledged French supremacy, it was deemed absolutely essential that the first French universal exhibition should give a prominent place to the fine arts.

Not all art works submitted were accepted. Those rejected by the judges had the word Refusé stamped on the back of the canvas -- an action which would make it difficult for the artist to sell the work at a later time.

The first problem to be overcome was the objection of artists to exhibiting next to industrialists. At first, the objection was met by promising that the art exhibit would be held in several rooms of the Louvre. But this plan fell through; and the exposition commissioners decreed that the artists must hang their works in a long gallery attached to the Palace of Industry. To the relief of the artists, it soon became apparent that the Palace of Industry was inadequate to hold all the machinery exhibits, so the new annex was made part of the industrial exhibit, and the artists were shunted off to a temporary but graceful structure built on the Avenue Montaigne under the supervision of Hector LeFuel.

Caricatures of "The Typical Visitor to the Industrial Exhibits" and "The Typical Visitor to the Art Exhibits" at the 1855 Exposition Universelle

For the devotees of art, the fine arts section of the exposition provided a battle as thrilling as the Crimean campaign. Works of art from around the world were on display. But all eyes were on the French artists, and particularly on the rival works of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Eugène Delacroix. Praises and disparagements were hurled back and forth among the journals of the day, and gave the salons and cafés a never-ceasing supply of catalysis for argument. Ingres seemed represent all that was best in the "classic" school of French academic art: idealized subjects, painted with a fine and precise brushstroke. Delacroix was the major exponent of the Romantic school: heroic subjects, rendered in bold, dramatic colors (though Ingres complained that his rival "painted with a drunken brush").

Both artists were awarded gold medals by a jury only too happy to acknowledge a double supremacy in French art. By the end of the exposition, though, there was little doubt but that Ingres had won the palm. Delacroix was well-represented, with 35 works on exhibit; but Ingres had a larger room reserved exclusively for his 43 works. Delacroix had on display numerous scenes from Shakespeare, plus a full complement of religious and historical scenes, exotic locales, and even a still life. Ingres, though, showed more shrewdness in his choice: enticing nudes, sacred events, numerous portraits of important men and women, allegorical scenes — the choicest selection of half a century's work. At the center of the exhibit were two pictures of Napoléon I : one showing the youthful Bonaparte as First Consul; the other, an immense circular painting of The Apotheosis of Napoléon — works well-calculated to please Prince Napoléon, who headed the Fine Arts jury.

Ingres, "The Apotheosis of Napoleon" watercolor sketch. The original oil painting was destroyed in 1871.

Even critics who were temperamentally closer to Delacroix stood in awe of Ingre's calm mastery of formal arrangement and the precise confidence of line. Writers like the flamboyant Théophile Gautier bowed down before the cool grandeur of Ingres "on a golden throne at the summit of art." Prince Napoléon himself declared that the work of Ingres embodied "the very archetype of eternal beauty." As head of the fine arts jury, the Prince obtained from the Emperor a nomination to make Ingres a Grand Officier de la Légion d'honneur — the highest award attained by any exhibitor at the Exposition.

At the time, the art of Ingres seemed secure on its throne at the summit, with the work of his rival only slightly lower in elevation. But meanwhile, down in the valleys, a rustic artist submitted some 30 pictures to the selection committee. Eleven were accepted; and, though they attracted little attention in 1855, the works of Gustave Courbet would, in the passage of time, come to outshine his more respected and respectable contemporaries.

Given Courbet's new vision of the world and the painter's métier, it is a credit to the jury that they recognized his talent and allowed eleven canvases to be exhibited. But eleven was not enough for the young master — especially since the jury had rejected two works by which Courbet set great store: L'Enterrement À Ornans and L'Atelier. To show the world what he really meant to show with his works, Courbet opened a one-man show directly opposite the exposition site. For an unknown artist to hold a one-man show constituted, in 1855, an act of considerable audacity and egotism. But to open it in plain view of the exposition grounds was a gesture of stupendous arrogance, which the French intellectuals alternately mocked and applauded.

Courbet crowns himself the greatest artist of the exposition -- a satire on Courbet's presumption

Anglophiles and Anglophobes

Supremacy in the fine arts, and especially in painting, belonged incontestably to France. But contemporary French commentators about the exposition reveal a surprising Anglophilia in their remarks. Baudelaire, in his review of the art of the exposition, takes pains to tell his readers that the English are a gifted and great people:

I want to start with the glorification of our neighbors, of these people so admirably rich in poets and novelists, the country of Shakespeare,Crabbe, Byron, Maturin and Godwin and their countrymen Hogarth and Gainsborough.(14)

Baudelaire himself had learned the English language quite well — well enough to translate Edgar Allen Poe into French. But his praise of English painting — coming as it does in the middle of an essay paying respects to Ingres and Delacroix — comes as a surprise.

Delacroix himself expressed admiration for the "particular charm of the English school" of painting. But the remarks of the great French master reveal what amounts to a double agenda: sincere admiration of the English, and praise of the English as a springboard for criticizing what he sees as reprehensible in France. British painters are lauded for their "realistic touch": "landscapes, seascapes, war paintings... all charming, nicely realized and well-designed."(15) With only a few exceptions (including Meissonier, Decamps, and a few youthful works by his rival Ingres), French painting is "obtuse," "vulgar," "banal," "without intention, without warmth." He goes on to contrast what he considers to be the ineptly illustrated French l’Illustration magazine with a "a parallel journal published in England" — undoubtedly The Art Journal — "in order to get an idea of the softness and insipidity of most of our publications."(16)

Delacroix’s essay is clearly more pointed in its criticism of things French than in the praise of things English. His remarks may well be calculated more to spur French art than to please his English neighbors. But for Theophile Gautier, the English deserved praise if for no other reason that they produced William Shakespeare. Shakespeare was performed in English at Parisian theaters in 1855, and inspired Gautier to suggest that an Exposition Universelle de Shakespeare should be held to honor "that encyclopedia of the human race."

For once, the Emperor and the intellectuals were at one. Napoleon III had learned his love for English institutions first hand during the course of his early life of exile. He returned to France, not just with a general feeling of gratitude, but a genuine love of many English institutions. Baron Haussmann used to complain that all the new and revamped parks in Paris had to have "the inevitable grotto" because the Emperor had developed a passionate fondness for them in their settings in English parks.

Queen Victoria’s visit capped all these sentiments, and brought them to the general public. The French and the English were fighting side by side in the Crimea; the Emperor liked English institutions; Gautier, Delacroix, and Baudelaire found my to admire in the art and thought of France’s ancient enemy. Small wonder that the crowds cheered themselves hoarse as the queen and consort rode through the streets of Paris.

There were dissenting voices, of course. Ernest Renan saw the influence of the English idea of "comfort" on French design was a bad sign for France and the future. The English preference of "the comfortable" reflected an idea very un-French and at odds with the higher ideal of style. Renan saw a part of this struggle as the Celtic genius for spirituality versus Saxon obsession with mere things. In 1798 or 1815, the French public may well have agreed with Renan. But in 1855, his was a voice in the wilderness, crying out against Saxon vulgarity and the replacement of spiritual concerns with an obsession with mere things.(17)

THE "PHYSIOGNOMIC TRACE"

“Expressions of Pierrot: A Series of Heads”-- salt prints by Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (also known as Nadar) and his brother, Adrien Tournachon

The exposition jury awarded Adrien Tournachon a gold medal for these studies, not so much for their quality as photographic prints but as for their attempts to capture the “physiognomic traces” of human emotion. During the past several decades, writers had put forth the theory that human character was made manifest by the physical expression of emotions. (27) But before the invention of photography, such expressions were fleeting: a painter might portray them; but the result would inevitably represent the painter’s interpretation of the emotions. The expressions themselves vanish in an instant.

With the invention of the photograph, anyone could study the direct imprint of such expressions on photographic paper. A photograph could therefore, it was thought, be an objectively true record of an expression of emotion. However, cameras were large and cumbersome, and film speeds were slow. So the Tournachon brothers conceived the idea of photographing an expert mime — Charles Debureau, son of the famous Baptiste Debureau — who would compose his features into attitudes of surprise, anger, sorrow, and other primary emotions for study of the physiognomic traces captured by the camera lens. The Tournachon brothers were rewarded with the gold medal because of the positive contribution of photography to the study of human character.

There were some contemporaries, however, who were deeply suspicious of such transfer of personality to the photographic print. Balzac — whose own work excelled in conveying personality traits through minute physical descriptions of his characters (28) — believed, as Rosalind Krauss has noted, that “all physical bodies are made up entirely of layers of ghostlike images, an infinite number of leaflike skins laid one on top of the other. Since Balzac believed man was incapable of making something material from an apparition, from something impalpable — that is, creating something from nothing — he concluded that every time someone had his photograph taken, one of the spectral layers was removed from the body and transferred to the photograph. Repeated exposures entailed the unavoidable loss of subsequent ghostly layers, that is, the very essence of life.”(29)

This belief — shared by many of Balzac’s famous contemporaries such as Theophile Gautier and Gerard de Nerval — was widespread, and culminated, later in the century, in the practice of printing photographs of dead people using, as part of the photographic prints, the ashes of the person cremated.(30)

STONE AND IRON

In spite of the official appreciation of art and photography, though, the real action was being played out elsewhere. The major building of the fair was not the Palais des Beaux Arts, after all: it was Barrault's and Viel’s Palais d'Industrie. Napoléon III opened the exposition at the Palais, calling it a "temple of peace." The major exhibits were housed here — relegating the fine arts exhibits, by implication, to the status of side shows.(17a) The Palais was the one legacy of the 1855 exposition universelle to the city of Paris, and remained so until it was torn down in 1897 to make way for the 1900 fair.

The main entranceway to the palace set the tone for the entire exhibition. The visitor standing before the main doors was greeted by an immense flanking movement that towered and spread before him. There were small, box-planted and severely trimmed trees spaced all along the front of the Palace — symbolic of the reduced and controlled place of nature in the industrial scheme of the world. The entranceway itself was in the shape of a triumphal arch — a shape that recalled both the glories of the Roman Empire and the Arc de Triomphe of Napoleon I. Two bas-relief angels blew their trumpets in the space between the massive curve of the entrance vault and the words Palais d’Industrie in the architrave above. The frieze showed a scene derived from Greek religious architecture: supplicants bearing the gifts of art, agriculture and industry, all surrounding a bas-relief bust of Napoleon III crowned with a laurel wreath. Atop the entranceway was a heroic figure of France, crowned with a star halo, and holding a victory wreath in each hand. Reclining at her feet are twin symbolic figures of Art and Industry.

The three-part message of the entranceway was carefully calculated to express the entire idea of the exposition universelle. The triumphal arch stood for the continuity of empire, from classical times down to France in the nineteenth century. The frieze states that it is the munificence of Emperor Napoleon III that such an empire, and such riches as the visitor will soon find within the walls of the palace, makes possible for his people. The Elias Robert’s crowning sculpture states the loftiest goals: France has convened the peoples of the world to crown art and industry.

Two of those three symbolic statements have been relegated to the pages of history. The empire is no more, and Napoleon III is probably the most ill-remembered and maligned of all French monarchs. But France continues to regard herself as the rightful leader of art and industry of Europe, if not the world.

In 1855, the French public — with some notable exceptions — was justifiably proud of what the Palais d’Industrie represented. But the public was surprised to learn that the government would not be paying for the new Palace. In an effort to save money and encourage private enterprise at the fair, the costs of erecting and maintaining the building were given over to a private guaranty company. Under the terms of the agreement, the city would donate the land, and the company would operate the building until 1898, after which time the Palais would become government property. For many years after the exposition, the Compagnie du Palais de l'Industrie rented out the building for shows and expositions of all sorts. Eugene Delacroix thought he saw in this venture the insidious influence of barbarism from across the Atlantic:

They are talking about selling off the Champs-Elysées to speculators. The Palace of Industry is to blame for this. When we resemble the Americans more, we will even sell the Tuileries Gardens as a vacant lot. (18)

In spite of the Emperor's glowing inaugural address, the Palais d'Industrie was almost an embarrassment to the entire exposition. Though commissioned in 1852, the building was still incomplete by the opening day. One cynic remarked that the Palais resembled one of those ludicrous theatrical performances "where the curtain accidentally rises on the actors en déshabillé." But once inside, visitors would marvel at the French answer to the Crystal Palace. The enormous iron and glass barrel vault, measuring 48 meters from side to side, was more than twice the span of the central hall of the Crystal Palace. Double rows of galleries flanked the high central vault, giving ample space for exhibitors while at the same time leaving the central space uncluttered for large events. For some 30 years, French architecture had led the world in the development of iron and glass architecture. Now, it seemed, the leadership had been regained.

But to the practiced eye, the victory was an illusion. Worried that the iron beams would exert too much lateral thrust, Barrault shored up the base of the piers with huge lead abutments. Still fearing a collapse, he sheathed the outside of the Palais with stone. Here, at the moment of utmost daring in modern architecture, it seemed as though Barrault had lost his nerve, and resorted to medieval buttressing techniques — "an imitation of cumbersome Gothic principles of construction,"(18A) in the judgement of architectural historian Siegfried Ghiedion.

Criticism was not long in coming. Octave Mirabeau, commenting on the Palais d'Industrie as a focal point of the Champs Elysées, compared the building to "an ox trampling through a rose garden." Subsequent architectural critics were almost universal in condemning the "heaviness" of the building. Even so, the Palais served as a hall for numerous exhibits and social events until its destruction in 1897. Charles Garnier, architect of the famed Opera House and president of the French architectural society, noted at the time of its demolition that no architect of note wanted the Palais preserved.

In the face of such condemnation, though, it is worth recalling that the Palais had a line of influence all its own. The sheathing of an iron and glass structure with a stone casing was imitated in the London Exposition of 1862 and the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and even in the very buildings that were destined to replace the old and much maligned Palais d'Industrie. The stone-sheathed Grand Palais and Petit Palais (built for the 1900 exposition universelle) stand today where the Palais d'Industrie once trampled through the rose garden of the Champs Elysées. The Palais d’Industrie is the grandparent of what one architectural historian has called "the most important as well as the most interesting [buildings] in terms of construction and architecture." (18B)

PRIZES FOR ALL

The Exposition Committee wanted to make sure that as many exhibitors as possible would be pleased with their participation in the event. To be chosen by the selection committees was in itself an honor. Once admitted to the Exposition, a second battery of juries ranked the works of industry and fine arts. Of the 23,954 exhibitors, 11,033 won prizes. Honorable mentions, third-, second-, and first class medals, grand medals — awards were distributed liberally, but with enough gradations of class to give the top echelons of prizewinners a feeling of genuine triumph, and the others a sense of recognition.

Prince Napoléon attempted another innovation with regards to the distribution of awards. In making a judgement of excellence about products coming from large firms, the Prince urged the juries, every effort should be made to single out the worker or the foreman who supervised the work. The company itself should not be the sole recipient of the award for high-quality work. But very few such awards were made. The Prince attributed this failure to the reluctance of the juries themselves, and to the unwillingness of companies to single out their best workers for praise.

It was not only the exhibitors who profited from the Exposition. 1855 was a bonanza year for Parisian hotels, restaurants, music halls, and all manner of places dedicated to the business of pleasing visitors. The total income of Parisian theaters showed most convincingly that an international exposition meant booming business. In 1854, the total receipts for all theaters in Paris amounted to 12 million francs; in 1855, 16 million; in 1856, 14 million. And in the theater itself, new ideas abounded. In addition to the standard repertoire, new and exotic themes took the stage. Dioramas and panoramas showed the voyage to California and the course of the Mississippi River. Paris herself was the subject of a new kind of drama that year — representations on stage of the historical development of the city through the ages. Here, perhaps, is the germ of the famed "Histoire du Travail" and "Vieux Paris" sections of later expositions.

The exposition itself inspired several occasional pieces: Dzim Boum Boum, Revue de l'Exposition, and even a Vision of Faustus or the Universal Exposition of 1855 by Sébastian Rhéal, in which Dr. Faustus raises a toast to "the second renaissance of the muses, the new alliance of nations in all our future Olympiads!" Like many other writers of the day, Rhéal saw the exposition universelle as an opportunity to turn from military competition to peaceful "Olympiads" of art and industry. The character of Poetry announces: "The prophesied age begins; the sword is transformed into the plowshare."(19) Later, Rhéal voices the belief that France is rising to her destiny:

We shall forge the chain of alliance,

And bring about, before the vast populace,

The dream of the poet and the great Emperor!(20)

CRITICS

In spite of the official ceremonies honoring progress, in spite of the panegyrics of writers such as Rheal and Arnoux, there were strong voices who found little to admire, and much to fault, in both the conception and the execution of the first French exposition universelle. Some, like Mirabeau, found the Palace of Industry a blight on the face of Paris. Others, like the Goncourt brothers, saw the exposition as evidence that the vast majority of visitors of the exposition were there only to be entertained: "The people there line up only to see the exhibit of royal diamonds." (21)

It was the philosopher and historian Ernest Renan, though, who delivered the most devastating critique of the whole affair. A few days after the close of the exposition, Renan published an essay in the Journal des débats entitled "The Poetry of the Exposition." The title of the essay alone was a gauntlet thrown down to the cheerleaders of the exposition. There was no poetry there, of course. That was one of Renan’s major points: the exposition showed things, not ideas. The whole affair, said Renan, was remarkable for its lack of intellectual or spiritual purpose: "For the first time, our century has brought together great multitudes of people without giving them an ideal goal [un but idéal]." Instead, "the strongest minds of Europe are occupied in deciding which nations make the best silk or cotton."(22) What a waste of talent in a trivial enterprise!

But Renan has a further objection, one fundamental to his own thought: "The useful does not ennoble." By overemphasizing machines and "accessories," the government is promoting and pandering to a universal consumerism.

Virtue, genius, science (when it is disinterested and only seeks to penetrate the enigma of the universe), military valor, saintliness — these are the things that correspond to the moral, intellectual, or aesthetic needs of man. All these have the power to ennoble. (23)

Renan’s essay is in every respect the voice of the past, the guardian of traditions that the organizers of the expositions, from 1798 onward, were trying to replace. Renan blasts the regime of the Second Empire for confusing "the liberal arts and the servile arts [les arts serviles]." Previous exposition organizers had been at pains to rename the old mechanical arts the useful arts in an attempt to elevate their status. Renan is determined to plunge them back to their former feudal status. The servile cannot be noble. And "that alone is noble which supposes an intellectual and moral value in man." The whole idea of an industrial exposition, therefore, is a moral mistake of the first order. It seeks to replace poems with bolts of cotton, French beauty with English comfort, nobility with servile utility.

Charles Baudelaire added his voice to Renan’s objections. In a review of the art exhibit at the exposition, Baudelaire pauses to voice his skepticism of the whole idea of Progress.

If the commodities of today are better and cheaper than those of yesterday, then material progress is incontestable. But where, I ask you, is the guarantee of progress for tomorrow? Though the disciples of the philosophies of steam and chemical burners might propose that progress is an infinite series — where is the guarantee? (24)

Baudelaire thus questions the whole idea of progress as an ever-rising improvement in human conditions. History and biography contain numberless examples of cultures and individuals cut off in their prime, or declining after an initial series of successes. Who is to say that our own industrial progress will not suffer the same fate?

But the voices of Mirabeau, the Goncourt brothers, Renan and Baudelaire were drowned out in the chorus of popular and governmental enthusiasm for the event. The belief in progress by the application of technology to daily life had been germinating and growing for over half a century; and the solitary voices of writers, no matter how eloquent, had no power to divert — much less to stop — the momentum of the universal expositions.

FANFARE FOR AN EMPIRE

In the closing days of the fair, the Palais d'Industrie hosted an event that climaxed the aspirations and achievements of the entire exposition. Beneath the soaring central vault of the Palais, Hector Berlioz conducted a performance of his cantata, L'Imperiale, his Symphonie Triomphale, and his Te Deum.(25) For this event, Berlioz had brought in 1,200 performers, stationed in a gallery behind the Imperial throne. In spite of his Herculean effort in writing the music, assembling the performers and rehearsing them, the premiere performance was unexpectedly abridged by Prince Napoleon :

“Music was so unimportant on the day of the ceremony that in the middle of the opening piece (the cantata, L'Impériale, which I had written for the occasion) I was interrupted and obliged to stop the orchestra at the most interesting point, because the Prince had to make his speech and the music was going on too long.” (26)

Berlioz was philosophical about he interruption. After all, he had been well-paid, and would be given another chance to perform his music — without interruption — on the following day. On this closing occasion, only the general effect mattered: vast music in a huge building holding an immense international crowd honoring the conclusion of the first French universal exposition. It was a fitting tribute to the colossal ambitions and sizable achievements of the Emperor and the nation, all proclaiming with massive voice that French civilization once again was rising to her zenith.

POSTSCRIPT

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

NOTES

1 Quoted in Bouin & Chanut, Histoire française des foires et des expositions universelles ( Paris, 1980), page 62

2 Prince Napoléon, quoted in Deming, page 78

3 Laborde, Léon. Travaux de la Commission française sur l'industrie des nations, Vol. VIII, p. 234.

4 Rapport sur l’Exposition universelle de 1855 présenté a l’Empereur par S.A.I. Le Prince Napoleon, Président de la Commission (Paris, 1857), page 2

5 For a fuller dramatic account account of this event, see Edith Saunders, A Distant Summer (London, 1946)

6Jean-Jacques Arnoux, Le Travail Universel (Paris, 1856, n.p.)

7 L’Illustration, July 21, 1855, page 55

8 The United States, by contrast, seemed scarcely in the league of, much less a competitor to, the great European powers. America sent only 67 exhibits — though one of these, the McCormick reaper, defeated all others in a trial of effectiveness held during the exposition.

9 Rapport sur l’Exposition universelle de 1855 présenté a l’Empereur par S.A.I. Le Prince Napoleon, Président de la Commission (Paris, 1857), page 131

10 H. Marie-Martin, L’Exposition Universelle de 1855, septième groupe: Ameublement et décoration, modes dessin industriel, imprimerie, musique. Classe 24: Industries concernant l’ameublement et la décoration (Paris, 1855), page 429

11 Sculptural works could be seen at the national exhibits, but as examples of foundry casting, and not the product of artists.

12 Reports by the Juries on the subjects in the thirty classes into which the Exhibition was divided (London, 1852, p. 1547)

13 There may be more to this affair than meets the eye. Patricia Mainardi has discovered some documents that seem to indicate that there could have been a painting section at the Crystal Palace fair, but the French government refused to pay for shipping expenses to send French paintings abroad, so the idea was abandoned. See her Art and Politics of the Second Empire (New Haven, 1987), pages 29-30.

14 Charles Baudelaire, "Exposition universelle, 1855: Beaux arts," in Oeuvres complètes (Paris, 1961), page 958

15 Journal de Eugène Delacroix, June 17, 1885

16 ibid.

17 For a full discussion of Renan’s cultural/racial views on this matters, see Keith Gore, "Ernest Renan et l’art: autour des Expositions de 1855 et 1878 à Paris," in Revue d’Histoire Littéraire de la France, May-June, 1981, pp. 391 ff.

17a Entrance statistics — derived by the use of Destouches’ novel invention, the "counting turnstile" — bear out this fact. Some 906,530 paying visitors passed through the art exhibit; but some 3,626,934 paid to see the products of industry.

18 Journal de Eugène Delacroix, May 10, 1854

18A Siegfried Giedion, Raum, Zeit, und Architektur (Ravensburg, 1965), page 463

18B Wolfgang Friebe, Buildings of the World Exhibitions (Leipzig, 1985), page 36

19 Sébastian Rhéal (Sebastian Gayet):La vision de Faustus, ou l’Exposition universelle de 1855, comédie-apologue à grand spectacle (Paris, no date), page 29

20 ibid., page 35

21 E. and J. de Goncourt, Journal, texte intégrale établi et annoté par Robert Ricatte, Volume I (Paris, 1956), page 202

22 "La poésie de l’Exposition," in the Journal des débats, November 27, 1855, page 241

23 ibid., page 247

24 Charles Baudelaire, "Exposition universelle, 1855: Beaux arts," in Oeuvres complètes (Paris, 1961), page 958

25 Traditionally, a "Te Deum" is sung in Notre Dame to commemorate a great victory, such as the defeat of the English army in 1436 and the expulsion of the Nazi army in 1945.

26 Memoirs of Hector Berlioz, translated by David Cairns (New York, 1969), page 483. On the following day, however, when the paying public was admitted, Berlioz himself was able to bring together music and technology that fit well into the spirit of the exposition. A Belgian inventor gave Berlioz a device that wired together several electric metronomes. Berlioz was conducting the main orchestra, while 5 sub-conductors conducted the vast choirs spread out through the Palace of Industry. By moving the bar on his own metronome with his little finger, Berlioz could instantly transmit indications of change of tempo to the subconductors. Berlioz loved this device, and tried to interest others in its application — with limited success.

27 See Johann Caspar Lavater, The Art of Knowing Man by Means of Physiognomy (1783) and the writings of the early photographic pioneer, William Henry Fox Talbot.

28 Balzac emphatically asserted that he was not writing fiction. He referred to himself as “the secretary of society” and that his works were “instruments of scientific inquiry.”

“Realize this:” he wrote of his Père Goriot, “This drama is not an invention; it is not a novel. All is true. It is so true that you can all see hints of it in your own homes, in your own hearts, perhaps.”

Here, for example, is his description of Madame Vauquer, the mean-spirited and miserly landlady in Père Goriot:

“The room is to be seen in its full glory at seven in the morning, when madame Vauquer’s cat comes in...The widow herself traipses in shortly behind him in her battered slippers. A loop of imperfectly adjusted false hair dangles from under the net cap that adorns her head. The fat old face beneath it, with the nose jutting from the middle of it like a parrot’s beak; the podgy little hands; the body, plump as a churchgoer’s; the flabby, uncontrollable bust -- they are all of a piece with the reeking misery of the room, where all hope and eagerness have been extinguished and whose stifling, fetid air she alone can breathe without being sickened…

“Her face, with the bite of the first autumn frost in it; the wrinkles round her eyes; the expression in them that can quickly change from the set smile of a ballet dancer to the embittered scowl of a bill discounter.”

29 Quoted in Rosalind Krauss, "Tracing Nadar" (Photography,Volume Five, summer, 1978 -- an excellent discussion of the subject of physiognomic traces in the thought and pictorial representations in the nineteenth century

30 The practice of including cremated remains into works of art continues today:

https://www.cremationsolutions.com/other-cremation-options/cremation-portraits/

STATISTICS

Opening Date: May 15, 1855

Closing Date: November 15, 1855

Size of Site: 34 acres

Official Paid Attendance: 5, 162,330

Exhibitors: 23,954

Profit/Loss to Government (estimated): 8.3 million francs defecit

Top Official: Prince Napoléon, President

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnoux, Jean-Jacques. Le Travail Universel: Revue complète de l’art et de l’industrie exposées à Paris en 1855 (Paris, 1856, 2 volumes)

Baudelaire, Charles. "Exposition universelle, 1855: Beaux arts," in Oeuvres complètes (Paris, 1961)

Berlioz, Hector. Memoirs of Hector Berlioz, translated by David Cairns (New York, 1969)

Delaporte, Guillemette. "L’Exposition universelle de 1855 à Paris: confrontations de cultures et prises de conscience," in L’Ecrit-voir, Revue d’histoire des arts, number 6, 1985, pp. 5-10

Gore, Keith. "Ernest Renan et l’art: autour des Expositions de 1855 et 1878 à Paris," in Revue d’Histoire Littéraire de la France, May-June, 1981

The Exhibition of Art-Industry in Paris. (London, 1855)

Exposition des produits de l’industrie de toutes les nations, 1855. Catalogue officiel publié par ordre de la commission impériale (Paris, 1855)

Exposition Universelle de 1855. Catalogue des objets exposés dans la section des Etats-Unis d’Amérique (Paris, 1855)

L’Exposition Universelle de 1855, septième groupe: Ameublement et décoration, modes dessin industriel, imprimerie, musique. Classe 24: Industries concernant l’ameublement et la décoration (Paris, 1855)

Gorges, Edouard. Les Merveilles de la civilisation: revue de l’exposition universelle (Paris, 1855)

Guide dans l’exposition universelle des produits de l’industrie e des beaux arts de toutes les nations, 1855. (Paris, 1855)

L’Illustration, July 21, 1855

Léon, Paul. "La première exposition universelle de Paris, 1855," in La revue des deux mondes, number 9, 1855, pp. 49-62

Mainardi, Patricia. Art and Politics of the Second Empire (New Haven, 1987)

Pascal, Adrien. Visites et études de S.A.I. le Prince Napoléon au Palais de l’Industrie ou guide practique et complet à l’exposition universelle de 1855 (Paris, 1855)

Rapport sur l’Exposition universelle de 1855 présenté a l’Empereur par S.A.I. Le Prince Napoleon, Président de la Commission (Paris, 1857)

Renan, Ernest. "La poésie de l’Exposition," in the Journal des débats, November 27, 1855

Rhéal, Sébastian (Sebastian Gayet). La vision de Faustus, ou l’Exposition universelle de 1855, comédie-apologue à grand spectacle (Paris, no date)

Saunders, Edith. A Distant Summer (London, 1946)

Travaux de la commission française sur l’industrie des nations, publié par l’ordre de l’Empreur. Force productive des nations (Paris, 1857-58, 3 volumes)

Wikiwand, Exposition universelle de 1855: https://www.wikiwand.com/fr/Exposition_universelle_de_1855