The earliest microcomputers were really only of interest to electronic

tinkers and computer hobbyists. Their complexity and lack of useful

applications made them nearly worthless for any serious use by the

general public. Word Processing was one of the "killer"

applications that brought the microcomputer into the main stream.

The first commercial word processors were really dedicated

minicomputers connected to electric typewriters. Made by IBM,

Lanier, and Wang, these machines were completely proprietary.

The software resided in ROM and, at first, the only acceptable

letter quality printer was the IBM Selectric typewriter. Later,

daisy wheel printers made by Xerox (Diablo), NEC, and Qume were

made available. Such systems were expensive (10,000+ 1970 dollars),

but for many busy offices, they paid for themselves in a short time.

The first word processing program for microcomputers was The Electric Pencil

written by Michael Shayer. Originally it was only a text editor, but later

Shayer added formatting and printer features making it into a word processor.

Soon, Radio Shack released Scripsit for the TRS-80 while Apple Writter, Magic

Window, and Word Handler became available for the Apple II.

In 1978, word processors were fairly simple, performing basic functions like

word wrap and text scrolling. Then, along came WordStar and the written word

was changed forever.

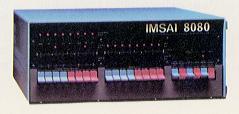

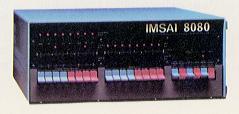

IMSAI Manufacturing

Soon after the introduction of the Altair 8800, Bill Millard started IMSAI

Manufacturing Corp. in San Leandro, CA. to develop a computer that was

compatible with the Altair, but overcame many of its short comings. The IMSAI

8080 was very much an Altair look alike, right down to the I/O plugin bus. It

did, however, offer front panel rocker switches, an active terminated bus

board, and a heftier power supply. This system became very popular with

commercial customers, finally outselling its protégé.

Soon after the introduction of the Altair 8800, Bill Millard started IMSAI

Manufacturing Corp. in San Leandro, CA. to develop a computer that was

compatible with the Altair, but overcame many of its short comings. The IMSAI

8080 was very much an Altair look alike, right down to the I/O plugin bus. It

did, however, offer front panel rocker switches, an active terminated bus

board, and a heftier power supply. This system became very popular with

commercial customers, finally outselling its protégé.

Seymour Rubenstein worked at IMSAI as a software developer. He envisioned a

time when software would propel the industry and wanted to be a part of it.

Rubenstein left IMSAI, to start Micropro International in San Rafael, CA,

taking programmer Rob Barnaby and Bill Lohse from sales with him. The first two

Micropro products were Supersort, a sorting program, and Wordmaster, a word

processor. Coded by Barnaby, both programs were released in September 1978

after only a few months in development.

One source indicates that Supersort and Wordmaster were actually written (by

Barnaby) at IMSAI and taken (Millard was not interested in marketing them) to

Micropro by Rubenstein.

Although Wordmaster was fairly popular it lacked a printing routine. Barnaby

immediately started coding WordStar - adding print routines and menu selected

formatting commands.

According to Rubenstein, Barnaby was the "mad genius

of assembly language coding". In four months he wrote 137,000 lines of

bulletproof code, the equivalent of 42 man years according to IBM's in-house

production benchmark. WordStar ran on the CP/M operating system, and with

Rubinstein and Lohse's marketing efforts, quickly dominated the field. It was

ported to every brand of CP/M computer on the market. When Adam Osborne came

out with his Osborne portable computer, he included a free suite of software

applications with each system. Others soon followed his lead and WordStar, the

included word processor, became the standard. Each computer maker provided the

user manuals and program media making this arrangement hugely profitable for

Micropro.

By the time version 3 was released, WordStar included context sensitive

on-line help, mail merge, and Correct-It, a stand-alone spell checker. Copy

protection had been dropped in version 2. WordStar basically invented the idea

of what you see is what you get (WYSIWYG), albeit character style. They

were also the first to use overlay files, which later evolved into DLLs

(Dynamic Link Libraries).

Early keyboards had no function keys or cursor movement keys, but they did have

a control key. The Control key, plus one or two character keys, was used to

move the cursor on the screen, format text, and provide all kinds of program

navigation.

When the IBM PC was released in 1981, WordStar was ported to DOS. Function and

cursor control key support was added, but it still retained its handy Control

key formatting.

Meanwhile, two of WordStar's top programmers, Barnaby and a later hire Peter

Mierau, left Micropro to form NewStar Software, Inc. where they produced a

WordStar work alike called NewWord. They improved upon the WordStar model and

competed successfully with it.

As the demand for word processing increased, large companies were stuck with

typing pools accustomed to using dedicated word processors. WordPerfect came

out with a system that ran on the PC, but used the familiar keystrokes of the

dedicated word processing machines.

On the PC platform WordStar met increased competition particularly from

WordPerfect with its easier to learn interface and unlimited, free technical

support. New users, and those coming from dedicated word processors, preferred

WordPerfect while users staying with or migrating from the CP/M world loved

their WordStar.

Microsoft, fast becoming rich from its sales of PC-DOS and MS-DOS, saw the

potential in application software and came out with its own word processing

program, Word. To get it into the hands of users quickly, Microsoft distributed

free Word disks with several popular computer magazines. Of course, the

full-featured program with documentation was then offered for sale.

The PC became popular in colleges, and while expensive commercial word

processors were out of reach for most students, a program called PC-Write was

sold as cheap shareware. This program used the familiar keystrokes of WordStar,

but produced ASCII output that could be converted for use by most other

programs and handled by all printers.

Meanwhile, WordStar was falling behind. Since MicroPro realized they had no one

on staff who understood the WordStar code enough to do more than minimal

patches, they wrote an entirely new word processor called WordStar 2000. 2000

used entirely different keystroke commands alienating their WordStar installed

based, changed the file format, and was generally a very inefficiently written

program. It flopped miserably.

Meanwhile, WordStar was falling behind. Since MicroPro realized they had no one

on staff who understood the WordStar code enough to do more than minimal

patches, they wrote an entirely new word processor called WordStar 2000. 2000

used entirely different keystroke commands alienating their WordStar installed

based, changed the file format, and was generally a very inefficiently written

program. It flopped miserably.

To get back in the game, MicroPro bought NewWord, rehired the principals, and

groomed a new version of NewStar as WordStar 4.0. Peter Mierau, principal

programmer for WordStar 4.0, did the major redesign work through WordStar 5.0,

and then left again to form Roxxolid (pronounced "rock-solid")

Software.

Somewhere along in here, MicroPro reorganized as WordStar International

Corporation. After WordStar 7.0 was released, they realized they needed a

Windows based program and lacked the resources to write one themselves from

scratch. Porting the DOS version was out of the question; the effort of doing

that had nearly killed WordPerfect Corporation, a much bigger and richer

company, and resulted in a slow program that no one liked (the DOS folks stayed

with the DOS program and the Windows folks thought it looked too much like a

DOS program).

WordStar licensed the source code to a smallish desktop publishing program

called Legacy, from a company named NBI. WordStar Legacy was essentially that

code with some file conversion and keystrokes bolted on. A substantially

improved (internally) version was soon released as WordStar for Windows 1.0.

This all happened during the Windows 3.0 time frame. [This author never tried

Legacy, but WSWin 1.0 was so unstable that a simple two page letter could not

be written without a crash.]

WordStar for Windows 1.5 was the Windows 3.1 update; faster and more stable.

WordStar for Windows 2.0 was a nearly complete rewrite of the NBI code, and was

a quite capable small desktop publishing program with good text editing

capabilities.

Unfortunately, a few weeks before initial release, Softkey International bought

the company. The programmers finished what they could and Softkey released it

with the already printed manuals at a bargain price of $49. It really needed

one last grooming and a 2.1 bug fix release, but that never happened. The file

format was probably its biggest weakness; it led to bloated files,

slower-than-necessary performance, and potentially flaky memory management in

complicated files.

More recently, The Learning Company bought Softkey - and WordStar has faded

away like an old soldier.

All modern word processors owe their existence to WordStar - perhaps one of

the greatest single software efforts in the history of computing.

Soon after the introduction of the Altair 8800, Bill Millard started IMSAI

Manufacturing Corp. in San Leandro, CA. to develop a computer that was

compatible with the Altair, but overcame many of its short comings. The IMSAI

8080 was very much an Altair look alike, right down to the I/O plugin bus. It

did, however, offer front panel rocker switches, an active terminated bus

board, and a heftier power supply. This system became very popular with

commercial customers, finally outselling its protégé.

Soon after the introduction of the Altair 8800, Bill Millard started IMSAI

Manufacturing Corp. in San Leandro, CA. to develop a computer that was

compatible with the Altair, but overcame many of its short comings. The IMSAI

8080 was very much an Altair look alike, right down to the I/O plugin bus. It

did, however, offer front panel rocker switches, an active terminated bus

board, and a heftier power supply. This system became very popular with

commercial customers, finally outselling its protégé.

Meanwhile, WordStar was falling behind. Since MicroPro realized they had no one

on staff who understood the WordStar code enough to do more than minimal

patches, they wrote an entirely new word processor called WordStar 2000. 2000

used entirely different keystroke commands alienating their WordStar installed

based, changed the file format, and was generally a very inefficiently written

program. It flopped miserably.

Meanwhile, WordStar was falling behind. Since MicroPro realized they had no one

on staff who understood the WordStar code enough to do more than minimal

patches, they wrote an entirely new word processor called WordStar 2000. 2000

used entirely different keystroke commands alienating their WordStar installed

based, changed the file format, and was generally a very inefficiently written

program. It flopped miserably.