ArtSeen

Gego: Measuring Infinity

On View

GuggenheimMeasuring Infinity

March 31–September 10, 2023

New York

One of the earliest pieces in Gego: Measuring Infinity is an intimate watercolor titled Vista de Caracas (1953). It was painted more than a decade after Gertrud Goldschmidt (1912–94), known professionally as Gego, fled Nazi Germany for her adopted home of Venezuela. From Tarmas, a coastal town outside of Caracas where she began making art, Gego could observe Venezuela’s rapidly modernizing capital from its rural periphery. In Vista de Caracas, the city looks remote and unmoored. The loose, inky lines dragged across a somber landscape create a mirage-like effect, as if the urban center were transforming before our eyes. This early watercolor both hints at Gego’s signature abstraction, which she would later hone in her sculptures, and figures in succinct strokes the frenzied social, political, and economic conditions that would touch—but not threaten—her lifelong work and vision.

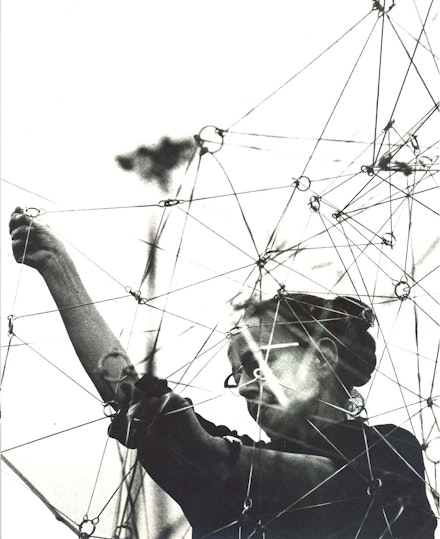

Having trained as an architect and engineer at what is now the University of Stuttgart, Gego began to develop her artistic practice in her forties and is best remembered for her Reticuláreas, immersive net-like installations made from steel wire that she constructed by hand and debuted in Caracas in June 1969. Despite the radicality of her practice in the context of twentieth-century modernism, Gego’s work has been largely overlooked in the US, an issue that the Guggenheim sought to redress in her first museum retrospective in New York. Building on a selection of nearly two-hundred sculptures, drawings, prints, textiles, and artist’s books, Gego: Measuring Infinity, curated by Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães and Pablo León de la Barra, attempts to summarize a rich and varied oeuvre through a spiraling procession of geometric constellations in the museum’s vertiginous rotunda.

The exhibition situates Gego’s personal approach to nonobjective art within the context of the political and economic realities of Venezuela during and after the dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez (1952–58). The works attest to Gego’s sustained resistance to geometric abstraction and Cinetismo, two regime-sanctioned styles adopted by artists such as Jesús Rafael Soto and Alejandro Otero. Rejecting the mainstream, Gego fostered her own visual language and social circles in the literal and figurative peripheries of Caracas. She did not get involved, as many did, in large-scale state-commissioned projects like the design of the main campus of the Universidad Central de Venezuela (UCV) led by the architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva in the early 1950s. Instead of thus associating herself with her predominantly male peers, Gego focused on cultivating a different form of social relation: one centered on direct pedagogy. Her devoted industrial design students, who met frequently in her home to discuss ideas, are, like her Reticuláreas, part of her legacy.

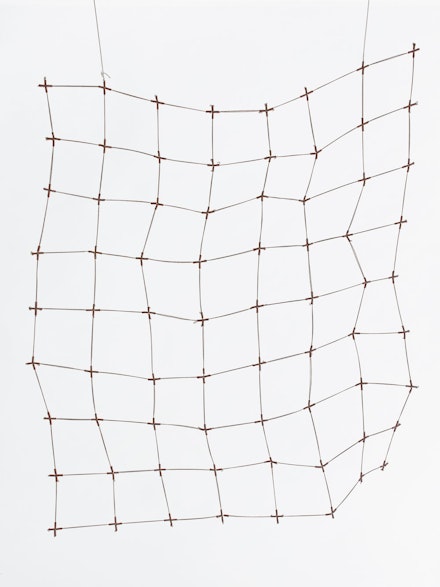

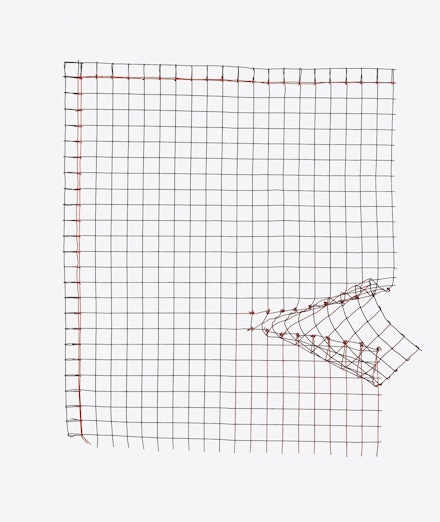

Gego taught basic composition and a famous spatial relations course known affectionately as “Gego’s Seminar” at institutions like UCV and the Instituto de Diseño Neumann, using a hands-on workshop model. She had her students experiment with basic geometric shapes and patterns in humble materials like sticks, straws, and thread—just as she did. As evidenced by the works in the Guggenheim show, the principles of abstraction Gego developed and advanced in her classes were then applied throughout her own oeuvre. Consider Reticulárea cuadrada 71/2 (1971/89) and Reticulárea cuadrada 71/11 (1971), two steel wire sculptures suspended side by side on the rotunda’s third ramp. The first resembles a rippling, gridded tapestry whose fine lines cross at darkened junctions reinforced with black plastic tubing. The second, narrower Reticulárea has more tubing than the first: the plastic appears like a jagged and roughly U-shaped scar running through the midsection of the fragile grid. Some of the junctions have also come undone; sections of the sculpture hang loose. The effect resembles a slashed screen door. Julieta González, Senior Curator at the Museo Rufino Tamayo in Mexico City, has compared Gego’s abstract works to Caracas itself, describing both as agents who have defied the imposition of modernity and its ubiquitous grids. Indeed, like a restless body politic, Gego’s wire sculptures expose the versatility of structures and the countless ways in which one can rupture rigid preconditions.

In her long-running Dibujos sin papel (Drawings without Paper, ca. 1976–1988), a series of small-scale, vertically hanging wall sculptures, Gego displays her devotion to handicrafts, which, as she emphasized to her students, were the basis of architecture. Perhaps the most surprising work in the series is Dibujo sin papel 87/13 (1987). Unlike its steel counterparts, this “drawing without paper” is made from a rectangular scrap of earth-toned nylon. The fabric—translucent, fraying, and lodging pins, springs, spirals, and stitches—casts a stain-like shadow on the wall behind it. The fragility of the material and Gego’s interventions articulate the tensions and irregularities of organic form. There is something both brave and wayward about this experiment that captures the spirit of the twentieth-century visionary. Like a generous teacher, Gego shares her principles by showing her hand. Every work is a demonstration.