Andrea Sabbadini[1]

David Lynch’s Blue Velvet is a coming-of-age story developed through a mixture of criminal and psychological investigations, transgressive sexuality, romantic love and psychopathic violence – all presented in its auteur’s unique filmic language. This is a language which appeals to our conscious curiosity to understand the movie’s narrative plot and its characters’ behaviour, but also invites us to relate them to our own deep-seated unconscious fears and desires.

Written and directed by Lynch in 1986, after such other original films as Eraserhead (1977), The Elephant Man (1980) and Dune (1984), Blue Velvet is a masterful work providing material sufficiently intense to deeply engage us spectators, both visually and emotionally, but so artfully created as to allow us to immerse ourselves in this material without becoming excessively disturbed by it.

In the process, this movie also explores (as Mulholland Drive will do fifteen years later) some unsavoury aspects of the underbelly of provincial American society, sometimes enriching its portrayal with ironic observations on family dynamics, in a space reminiscent of some of Edward Hopper’s paintings of airless interiors. In Knafo and Feiner’s words, Lynch ‘inverts the “American dream” – the idealised vision of a comfortable, orderly, secure and moral life – and […] undermines the illusion of goodness that bolsters one’s security and comfort’ (Knafo and Feiner 2002, p. 1445). The resulting picture is one of the contrast between an artificial, superficial veneer of petit-bourgeois respectability and a world of unspeakable secrets festering underneath.

Blue Velvet opens on a blue velvet curtain covering the whole screen. The plot takes us to the small American town of Lumberton (imaginary, though a real one by that name does exist in North Carolina). Here Jeffrey Beaumont (played by Kyle MacLachlan), a young man described by Lynch as ‘both innocent and curious’, returns from university to live with his mother and to manage his father’s hardware store following his hospitalisation. Jeffrey’s accidental discovery in the grass of a severed and bug-infested human ear leads to his meeting with the detective John Williams, who takes charge of the investigation, and with his daughter Sandy (Laura Dorn). By eavesdropping on her father, Sandy finds out that cabaret singer Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini), a most unusual specimen of femme fatale, is suspected to be somehow involved in the mystery of the amputated ear. She shares this bit of intelligence with Jeffrey, and they go together to the Slow Club to hear Dorothy sing Blue Velvet, a song made popular in the 1960s by Bobby Vinton. With Sandy’s ambivalent collusion Jeffrey then intrudes into Dorothy’s private space and personal life. Hidden inside a closet in her apartment, he witnesses Dorothy being verbally and sexually abused by criminal boss and psychopathic supremo Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) who, having kidnapped her son and husband, uses his perverse powers to control her. Discovered by Frank, Jeffrey has then to bravely engage in some frightening confrontations with him. To further complicate matters, Jeffrey becomes erotically involved with Dorothy and romantically with Sandy, until the narrative gets resolved into a deliberately unconvincing ‘happy ending’ and Blue Velvet closes on that same blue velvet curtain which had opened it.

I would like to suggest that the protagonists of Blue Velvet are ‘polymorphously perverse’ adults, probably evolved from the ‘polymorphously perverse’ children described in the second of Freud’s Three Essays on Sexuality (Freud 1905, p. 191). The word perversion is highly charged as well as intrinsically ambiguous. Sexual perversions refer to a variety of fantasies – from fetishism to necrophilia, to the two-sided coins of voyeurism/exhibitionism and sado/masochism – fantasies sometimes played out in actual activities involving relationships with other people, but mostly relegated to the dark corners of one’s unconscious mind.

Psychoanalysts working with perverse patients are used to experience in their own counter-transference something either analogous or more often complementary to what their patients express, such as an excessive curiosity about their exhibitionistic activities or some unnecessary cruelty in the interpretation of their masochistic attitude. This may be inevitable and, assuming the therapists will notice it and work-through it within themselves rather than enacting it, it could represent an indispensable tool for the understanding of the patients’ inner world.

Works of fiction have often portrayed characters whose perversions – whether just imagined or explicitly played out – were significant aspects of their existence: in books, on the stage, or on the screen. Focusing here just on cinema, the names of Hitchcock (Psycho 1960), Powell (Peeping Tom 1960), Buñuel (Belle de Jour 1967), Bertolucci (Luna 1979), Almodóvar (Matador 1986), Haneke (Hidden 2005) come to mind as auteurs who, among others, have explored such themes with special subtlety, courage and originality. Their movies, I suggest, induce in their viewers a certain amount of identification with the perverse side of the characters they portray, but also allow spectators to take some distance from them and to reflect on the meaning of their behaviour rather than become overwhelmed (for instance too excited, confused or frightened) by it.

This, I think, also applies to Lynch’s Blue Velvet, a movie pervaded throughout by perversions. Sandy eavesdrops on her father’s private conversations about suspects connected with the cut-off ear; Jeffrey voyeuristically spies on Dorothy’s erotic activities from the louvre door inside a closet; Dorothy expresses her own masochistic need, having succeeded in seducing Jeffrey, to get him to physically hurt her; Frank indulges in verbal and physical sadistic attacks on Dorothy and on anyone else in his proximity. The whole atmosphere of the film, and the behaviours of its protagonists, are profoundly perverse.

Of the several forms of perversions explicitly portrayed (such as Frank’s sadism), or just alluded to (such as his fetishism for blue velvet material) I would like to focus on the one which I believe runs through, and to some extent structures, the whole film: voyeurism (and, by implication, its complementary side, exhibitionism). I have elsewhere suggested that the term voyeurism describes what are in fact two phenomena, different though not always easily distinguishable, which I have called covert and collusive. ‘Covert voyeurism’, I wrote, ‘is a narcissistic form of penetrative aggression directly related to Primal Scene fantasies and it involves gratification through the watching of objects who are themselves unaware of being watched […]. Collusive voyeurism on the other hand involves the experience of pleasure through the activity of watching objects who are well aware that they are being watched […]. This is a more sophisticated form of perversion because it implies some recognition that others are not just extensions of one’s own self, but real persons responding to the voyeuristic activities of the subject and potentially getting themselves exhibitionistic satisfaction from being looked at’ (Sabbadini 2014a, p. 103).

In response to Jeffrey’s telling inspector Williams that he is ‘real curious’ about the severed ear, Sandy’s eavesdropping on her father’s conversation about it, a scene not shown in the film but implied by what happens next, is an instance of covert voyeurism. Jeffrey’s watching Dorothy being forced into a ritualised sexual encounter with Frank is an instance of collusive voyeurism: Dorothy is well aware of Jeffrey’s presence in the closet, and Jeffrey is well aware that she is well aware of it; but it is also an example of covert scopophilia insofar as Frank does not know of Jeffrey’s hidden presence in the room. Excited and horrified in equal measure, like a child exposed to the primal scene in the parental bedroom, Jeffrey watches on, and we with him as the fixed camera’s position invites us to identify with him. It could be argued that both Jeffrey (who had to hide in order to avoid being discovered by Frank) and Dorothy (who had to submit to Frank’s abusing and raping her) were forced to create such a voyeuristic/exhibitionistic scenario, rather than having voluntarily constructed it for their own sexual pleasure. However it is clear that, even if it wasn’t originally their conscious choice, both got some perverse gratification from finding themselves in that situation.

It would be easy to describe Dorothy as Frank’s sex slave as we learn that he can control her by holding her husband and son hostage. We watch him violently abusing Dorothy, his face distorted in a grotesque sneer (one that could have been imagined by Francis Bacon) and covered by a mask through which he breathes amyl-nitrate (a drug inducing a state of euphoria and visual hallucinations). But his sadistic and drug fuelled sexuality is complementary to Dorothy’s masochistic association of pleasure with pain; while Frank is raping her, Lynch’s camera closes up on the almost ecstatic expression on her face. Soon after this scene we watch Dorothy seducing Jeffrey and begging him to: ‘Hit me, hit me, HIT ME!’. Presumably, she could only reach orgasm, for reasons likely to originate from some childhood traumatic experience, when feeling hurt and humiliated. Jeffrey, reluctant at first and guilty afterwards, complies with her request, realising perhaps that ‘the condition for his sexual initiation entails his acceptance of his sadistic impulses’ (Knafo and Feiner 2002, p. 1448).

As a means to gratify these various forms of perverse sexuality, power plays an important part. The power of brute violence, the power of threats (Dorothy, wearing a blue velvet dressing gown, holds a carving knife in her right hand while sliding her left one inside Jeffrey’s underpants…), the power stemming from inducing fear in others in order to either control and dominate them or to obtain what they want from them: something that tyrants are well aware of, whether they are despots in dictatorial regimes or, like Frank, bosses of criminal gangs.

But what about the tyrannical power of internal fears, of those cruel, controlling forces which dominate the minds of individuals and make them slaves to paranoid fantasies? Often going unnoticed to others, the power of such persecutory fantasies can dramatically create for those affected by them the terrifying experience of living in hell. This may even apply to the world inhabited by Frank himself – a paranoid, psychotic inner universe which he can only survive by forcibly projecting it onto others. One aspect of it is his incapacity to think in other than concrete terms; for instance, he can only understand in such terms the metaphorical meaning of the ‘blue velvet’ in Dorothy’s signature song. We see him fetishistically caressing a piece of blue velvet material when listening to her singing in the Slow Club, placing the blue velvet belt of her dressing gown in her and his own mouth while raping her, and having pushed yet another blue velvet cloth in the mouth of her murdered husband – the man, we then discover, whose left ear had been cut off. Shot by Jeffrey, Frank dies holding Dorothy’s dressing gown across his arm.

With reference to Freud’s view about ‘two currents whose union is necessary to ensure a completely normal attitude in love’ (Freud 1912, p. 180), Bodin and Poulsen consider Blue Velvet as ‘a psychological tale about the young man Jeffrey’s attempt to find a solution in which the two currents of affection and sensuality form a synthesis and thus resolve his Oedipus complex […] out from an infantile sexuality towards a genital sexuality’ (Bodin and Poulsen 1994, p. 166).

Other psychoanalytic authors who have written about our filmalso focus on Jeffrey’s attempts to deal with his as-yet unresolved Oedipal issues. Sekoff suggests that ‘the signs and symbols of our dream-film boldly point to an oedipal drama. So boldly – with its broken fathers, beckoning women, forbidden desires and castrative threats – that the dream-text seems transparent […] When Sandy asks Jeffrey, “Are you a pervert or a detective?”, she knowingly points us to the latent structure of the dream-narrative. It is a rhetorical question, for we can see that the detective’s search will embody a perverse solution’ (Sekoff 1994, p. 423). Jeffrey, I would add, is both a detective and a pervert, insofar as all detectives are, so to speak, also perverts (if not the other way around). Here, then, Sandy’s question would relate not just to Jeffrey, but also to her own father who had chosen the detection of crimes as his professional activity. And it would relate to us, curious viewers of Blue Velvet…

Knafo and Feiner add that ‘as with Oedipus, whose need to penetrate the riddle of the sphinx led him to uncover his own crimes, Jeffrey’s investigations into the dark “under-inner-world” lead him to find the same darkness within himself’ (Knafo and Feiner 2002, p. 1445).

Jeffrey’s attempt to solve a mystery is then also a search for his own identity and masculinity, a search which brings him close to the affectionate ‘Madonna’ Sandy, as well as to ‘Whore’ Dorothy, the perverted victim whom he tries to rescue with his love for her. ‘Hurt me!’ she begs him. ‘No, I want to help you!’, he naively replies. Rescue fantasies, incidentally, are powerful motivators in many intimate relationships (psychoanalytic ones included) and often provide films with interesting plots (Sabbadini 2014b, pp. 80-89).

The severed ear that Jeffrey finds in a field demands some further reflections. It could be considered as just a kind of Hitchcockian MacGuffin, having as its only function to set in motion the events which follow, but being otherwise insignificant in itself. However, the fact that, of all possible objects, what Jeffrey finds half-hidden in the grass is a body part (and not, for instance, a briefcase full of dollars) charges it with special emotional connotations, for him and for the film’s viewers. Indeed, such an object is ‘a fairly substantial reminder that castration can become reality. If an ear can be cut off, so can other parts of the body’ (Bodin and Poulsen 1994, p. 166).

Psychoanalysts use the term ‘part objects’ with reference to the earliest forms of relationships that a baby entertains with others. It is only when a child can experience the existence of, say, a mother behind that prototypical part object which is her feeding breast that he can begin to engage in full object relationships; and even then, the ‘other’, entirely ‘good’ when present and satisfying his needs, is experienced as a different object from the ‘bad’ one when it is absent or unresponsive, a situation characterising what Melanie Klein (1946) described as the Paranoid-Schizoid Position.

What I am suggesting here is that part objects, including the cut-off ear found by Jeffrey, can induce in those who come across them later in life (our film’s protagonist, but also us spectators) a state of regressive, primitive, unconscious anxiety that would stem from their origins in the history of our human development. An instance, perhaps, of that disturbing phenomenon described by Freud as ‘the Uncanny’ (1919).

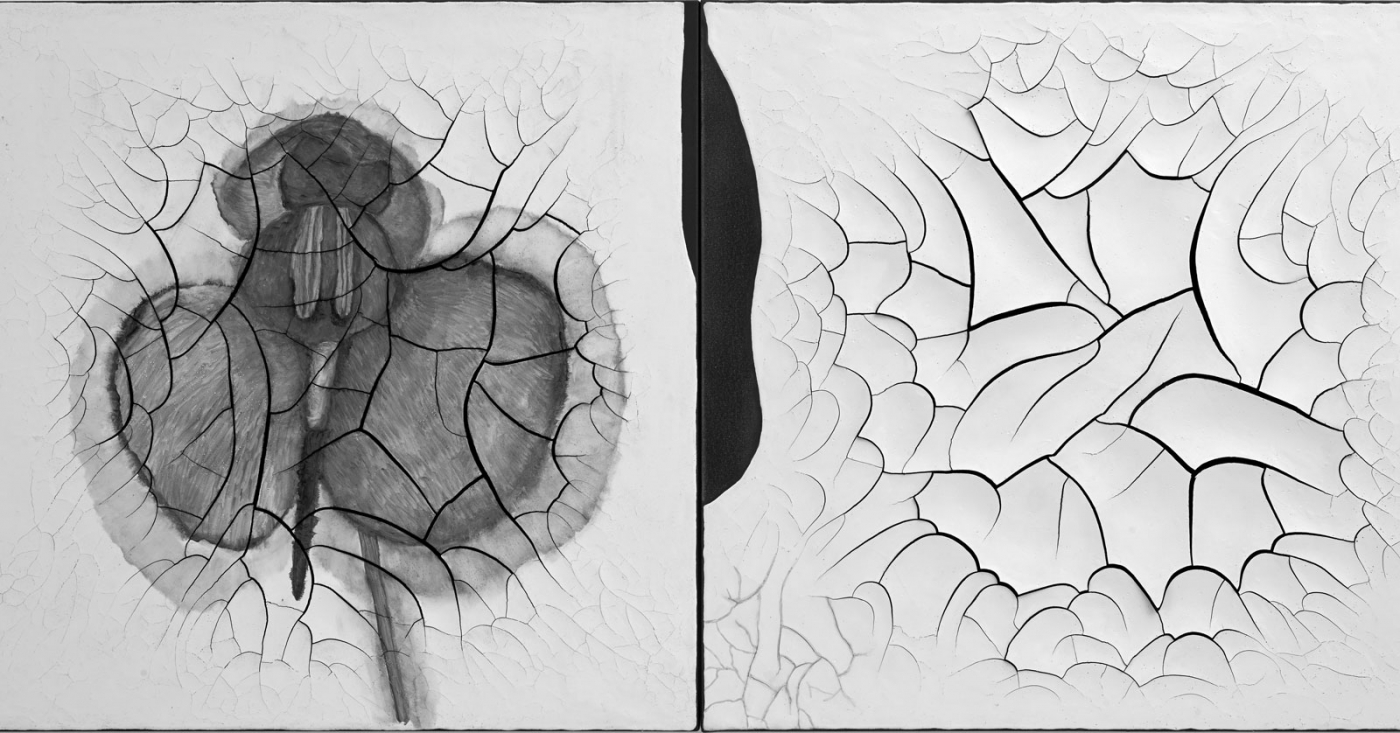

Movies, many of them in the horror genre, which induce such anxiety in their viewers by showing them macabre images of severed body-parts, are too many to be listed here. I shall only mention the eye being sliced with a razor blade and the hand with ants crawling out from a hole in Buñuel and Dali’s surrealistic classic Un Chien Andalou (1929); the castrated penis in the erotic Japanese masterpiece Ai no korida [In the Realm of the Senses] (Nagisa Oshima 1976) and the cut-off head found in a box in Joel and Ethan Coen’s Barton Fink (1991) – a film aesthetically similar to much of Lynch’s own work.

Un Chien Andalou (1929)

Blue Vevet (1986)

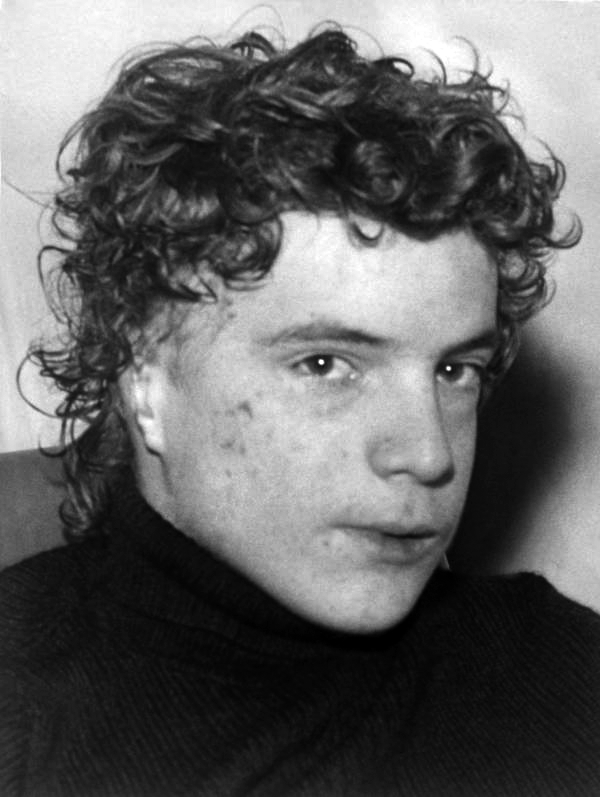

Not an eye, a hand, a penis, or a head in Blue Velvet, but… an ear! Such as the one, if I can freely associate here, missing from van Gogh’s head in his 1889 self-portrait, or that of the 16-year-old Paul Getty III, cut off by his abductors in 1973 and sent to his family to put pressure on them to pay the ransom – unlike the one in Blue Velvet which, abandoned as it is in a field, does not seem to have any other purpose than to be evidence of someone’s gratuitous, sadistic cruelty.

Van Gogh (1889)

Paul Getty III (1973)

I believe that the general significance of ears rests on the importance of the earliest experience of hearing in the formation of a child’s sense of identity. In parallel to the visual ‘mirroring’ described by Winnicott (1967), the holding auditory reflection of the child’s voice, sounds and noises (a process I call ‘echoing’) will allow the child not just to produce sounds, but also to learn to listen to them, enjoy them and recognise them as his own. For echoing to take place, the empathic and containing voice of his carers is an indispensable sounding-board to the child’s voice. Only by being talked and listened to by those who love him will the child feel sufficiently supported to learn to listen to himself and thus gradually develop an individual identity. Well-functioning ears (the child’s own and those of his carers) are essential body parts for such processes to occur (Sabbadini 2014a, p. 126).

While films, unlike psychoanalysis, provide us primarily with visual experiences, their auditory components are also important, whether they consist of conversations, noises or music (and Dorothy is a singer…). Is Lynch, by choosing an ear as the missing body part in his film, also trying to tell us something about cinema, about one of the organs involved in its reception? In fact, he does not just show us, and more than once, the severed ear, but there are also two sequences in which his camera first zooms inside the canal of that cut-off organ (at the beginning of Jeffrey’s amateurish investigation) and then zooms out of Jeffrey’s own ear (at the end of his hellish journey) – almost as if it was inside this internal organ that the whole narrative had taken place.

I suspect that Lynch got involved in the story of Blue Velvet, and so taken by his need to tell it in the visual language so distinctively his own (if not indifferent to other well established genres, such as film noir), that he was not too bothered about its reception. In fact, the film was a flop at the box-office before being recognised as a masterpiece by critics and becoming a cult movie for many of its viewers. In this respect Sekoff critically suggests that ‘Blue Velvet enters popular culture as another fetish – a commodity fetish that allows the purchase of an experience of the “dark side” of life’ (Sekoff 1994, p. 437). Lynch is a visionary, intuitive rather than intellectual filmmaker who, as actor Kyle MacLachlan has observed, ‘trusts his unconscious’ and makes choices based on it. As a result, his story-telling style is often free associative and requires from us viewers a complementary attitude of free-floating attention, or suspended disbelief, analogous to that familiar to those of us sitting behind an analytic couch. Here and there we have to allow ourselves to relinquish our wish to follow the logic of the story and rationally understand its development in order to accept its ‘primary process’ quality, to appreciate the original, artistic form in which it is presented, and even to enjoy its uncanny, perverse beauty. We can then find ourselves in a sort of dream-like (or nightmare-like) space, such as Dorothy’s dimly-lit, purple-coloured and womb-like apartment number 710, or the rooms where Frank’s associates guard their kidnapped hostages. A space, fascinating as it is mysterious, which made Dennis Hopper describe Blue Velvet as ‘thefirst American surrealist film’.

As both Jeffrey and Sandy state more than once: ‘It’s a strange world, isn’t it?’

Strange indeed! Thank you, David Lynch, for reminding us.

Abstract

I shall consider from a psychoanalytic perspective how Blue Velvet, dominated as it is by perverse relationships,presents us with ‘a strange world’ (a sentence repeatedly uttered by two of the film’s protagonists). I shall focus in particular on the theme of voyeurism, which also implicates us as spectators, and on the symbolic significance of the cut-off ear, the film’s iconic and emblematic MacGuffin.

A version of this article was presented at the “Freud/Lynch: Behind the Curtain” conference at the Rio Cinema in London, 26 May 2018.

Key-words

Blue Velvet, David Lynch, sexuality, perversion, voyeurism, ear

References

BODIN, G. and POULSEN, I. (1994). Psychic conflicts in contemporary language. An analysis of the film “Blue Velvet” by David Lynch. Scandinavian Psychoanalytic Review, 17(2): 159-177.

FREUD, S. (1905). Three Essays on Sexuality. Standard Edition 7. London: Hogarth Press.

——- (1912). On the universal tendency to debasement in the sphere of love. Standard Edition 11. London: Hogarth Press.

——- (1919). The ‘Uncanny’. Standard Edition 17. London: Hogarth Press.

KLEIN, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. In Envy and Gratitude and Other Works 1946-1963. London: Hogarth Press, 1975.

KNAFO, D. and FEINER, K. (2002). Blue Velvet: David Lynch’s Primal Scene. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 83(6): 1445-1451.

SABBADINI, A. (2014a). Boundaries and Bridges. Perspectives on Time and Space in Psychoanalysis. London: Karnac.

——- (2014b). Moving Images. Psychoanalytic Reflections on Film. London-New York: Routledge.

SEKOFF, J. (1994). Blue Velvet: the surface of suffering. Free Associations, 4(3): 421-446.

WINNICOTT, D.W. (1967). Mirror-role of mother and family in child development. In Playing and Reality. London: Tavistock, 1971.

Copyrights © Andrea Sabbadini, 2018

a.sabbadini@gmail.com

[1] British Psychoanalytic Society.