1st Anniversary Celebration Edition

Be Tasteful! Be Kitsch! A Critical Analysis of Social Standards of Beauty

Orbital Art in the Age of Internet and Space Flight Focus on German Artist Achim Mohné

The Medium Alone Is Not Enough: An Archaeology of Diffused Entities and Illusory Spaces

Figuring out the Female Presence in the Arts

Mass Culture, New Capitalism, and Its Codes

The Democratization of Art: Media and the Art of Publishing on Art

artstyle.international

Volume 5 | Issue 5 | March 2020

Academic Editors

Editor-in-Chief and Creative Director

Christiane Wagner

Senior Editor

Martina Sauer

Associate Editors

Laurence Larochelle

Katarina Andjelkovic

Natasha Marzliak

Collaborators

Charlotte Thibault

Denise Meyer

Jan Schandal

Marjorie Lambert

+1 347 352 8564 New York +55 11 3230 6423 São Paulo

The Magazine is a product of Art Style Communication & Editions. Founded in 1995, the Art Style Company operates worldwide in the fields of design, architecture, communication, arts, aesthetics, and culture.

ISSN 2596-1810 (Online)

ISSN 2596-1802 (Print)

Theodor Herzi, 49 | 05014 020 Sao Paulo, SP | CNPJ 00.445.976/0001-78

Christiane Wagner is a registered journalist and editor: MTB 0073952/SP

© 1995 Art Style Comunicação & Edições / Communication & Editions

Art Style

| Art & Culture International Magazine editorial@artstyle.international

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine is an online, quarterly magazine that aims to bundle cultural diversity. All values of cultures are shown in their varieties of art. Beyond the importance of the medium, form, and context in which art takes its characteristics, we also consider the significance of socio-cultural and market influence. Thus, there are different forms of visual expression and perception through the media and environment. The images relate to the cultural changes and their time-space significance the spirit of the time. Hence, it is not only about the image itself and its description but rather its effects on culture, in which reciprocity is involved. For example, a variety of visual narratives like movies, TV shows, videos, performances, media, digital arts, visual technologies and video game as part of the video’s story, communications design, and also, drawing, painting, photography, dance, theater, literature, sculpture, architecture and design are discussed in their visual significance as well as in synchronization with music in daily interactions. Moreover, this magazine handles images and sounds concerning the meaning in culture due to the influence of ideologies, trends, or functions for informational purposes as forms of communication beyond the significance of art and its issues related to the socio-cultural and political context. However, the significance of art and all kinds of aesthetic experiences represent a transformation for our nature as human beings. In general, questions concerning the meaning of art are frequently linked to the process of perception and imagination. This process can be understood as an aesthetic experience in art, media, and fields such as motion pictures, music, and many other creative works and events that contribute to one’s knowledge, opinions, or skills. Accordingly, examining the digital technologies, motion picture, sound recording, broadcasting industries, and its social impact, Art Style Magazine focuses on the myriad meanings of art to become aware of their effects on culture as well as their communication dynamics.

The Art Style Magazine’s Scientific Committee

Dominique Berthet is a University Professor, he teaches aesthetics and art criticism at the University of the French Antilles (UA). Founder and head of CEREAP (Center for Studies and Research in Aesthetic and Plastic Arts). Founder and director of the magazine Recherches en Esthétique (Research in Aesthetics). Member of CRILLASH (Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Literature, Languages, Arts, and Humanities, EA 4095). Associate Researcher at ACTE Institute (Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne). Art critic, member of AICA-France (International Association of Art Critics). Exhibition curator. His research focuses on contemporary and comparative aesthetics, contemporary art, Caribbean art, and Surrealism. He has directed more than 50 volumes, published more than 110 articles and ten books among which: Hélénon, “Lieux de peinture” (Monograph), (preface Édouard Glissant) HC Éditions, 2006; André Breton, l’éloge de la rencontre Antilles, Amérique, Océanie HC Éditions, 2008; Ernest Breleur (Monograph ) HC Éditions, 2008; Pour une critique d’art engage L’Harmattan, 2013.

Lars C. Grabbe, Dr. phil., is Professor for Theory of Perception, Communication and Media at the MSD – Münster School of Design at the University of Applied Sciences Münster (Germany) He is managing editor of the Yearbook of Moving Image Studies (YoMIS) and the book series “Bewegtbilder/Moving Images” of the publishing house Büchner-Verlag, founder member of the Image Science Colloquium at the Christian-Albrechts-University in Kiel (Germany) as well as the Research Group Moving Image Science Kiel|Münster (Germany). He is working as scientific advisor and extended board member for the German Society for Interdisciplinary Image Science (GiB). Furthermore, he is a member of the International Society for Intermedial Studies, the German Society for Semiotics (DGS) and the German Society for Media Studies (GfM). His research focus lies in phenosemiotics, media theory, and media philosophy, image science, perception studies and psychology of perception, communication theory, aesthetics, semiotics, film studies and history of media as well as theory of embodiment and cognition.

Marc Jimenez is a professor emeritus of aesthetics at University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, where he taught aesthetics and sciences of art. With a PhD in literature and a PhD in philosophy, he translated from German into French T.W. Adorno’s Aesthetics, August Wilhelm Schlegel’s philosophical Doctrines of Art, and Peter Bürger’s Prose of the Modern Age. Since 1986, when he succeeded Mikel Dufrenne, he directed the aesthetics collection Klincksieck Editions Collection d'Esthétique, Les Belles Lettres. He is a specialist in contemporary German philosophy, and his work contributed, in the early 1970s, to research on Critical Theory and the Frankfurt School. He is also a member of the International Association of Art Critics, participates in many conferences in France and abroad, and has been a regular contributor to art magazines. Recent publications: La querelle de l'art contemporain (Gallimard, 2005), Fragments pour un discours esthétique. Entretiens avec Dominique Berthet (Klincksieck, 2014), Art et technosciences. Bioart, neuroesthétique (Klincksieck, 2016), Rien qu'un fou, rien qu'un poète. Une lecture des derniers poèmes de Nietzsche (encre marine, 2016).

4

Omar Cerrillo Garnica is a Mexican professor and researcher, member of the National System of Researchers (SNI), Level 1. He is Ph.D. in Social and Political Sciences and a Master in Sociology at Universidad Iberoamericana, both times graduated with honors. He also made a post-doctoral research at the Autonomous University of the State of Morelos, where he searched about digital communication involved in social movements. Now, he is Director of Humanities at Instituto Tecnológico de Monterrey, Campus Cuernavaca. He is author and coordinator of the book Cardinales Musicales, Music for Loving Mexico, published by Tec de Monterrey and Plaza & Valdés. He is specialist in social and political analysis of art, music and culture; subjects throughout he participated in national and international academic events with further paper publications in Mexico, Chile, Argentina, Brazil and France. In recent years, he has specialized on digital media and its cultural and political uses.

Pamela C. Scorzin is an art, design and media theorist, and Professor of Art History and Visual Culture Studies at Dortmund University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Department of Design (Germany). Born 1965 in Vicenza (Italy), she studied European Art History, Philosophy, English and American Literatures, and History in Stuttgart and Heidelberg (Germany), obtaining her M.A. in 1992 and her Ph.D. in 1994. She was an assistant professor in the Department of Architecture at Darmstadt University of Technology from 1995 to 2000. After completing her habilitation in the history and theory of modern art there in 2001, she was a visiting professor in Art History, Media and Visual Culture Studies in Siegen, Stuttgart, and Frankfurt am Main. Since 2005, she is a member of the German section of AICA. She has published (in German, English, French and Polish) on art-historical as well as cultural-historical topics from the seventeenth to the twenty-first century. She lives and works in Dortmund, Milan and Los Angeles.

Waldenyr Caldas is a full professor in Sociology of Communication and Culture at the University São Paulo. He was a visiting professor at University La Sapienza di Roma and the Joseph Fourier University in Grenoble, France. Professor Caldas has been a professor since 1986 as well as the vice-director (1997-2001) and Director (2001-2005) of ECA - School of Communications and Arts, University of São Paulo. In his academic career, he obtained all academic titles until the highest level as a full professor at the University of São Paulo. Currently, he is a representative of the University of São Paulo, together with the Franco-Brazilian Committee of the Agreement “Lévi-Strauss Chairs,” and a member of the International Relations Committee of the University of São Paulo. He is also associate editor of the Culture Magazine of the University of São Paulo. Its scientific production records many books published and several essays published in magazines and national and international collections.

5

Content

Editor’s Note Essays

11 25 51 69 81 93 115

Be Tasteful! Be Kitsch! A Critical Analysis of Social Standards of Beauty by Waldenyr

Caldas

Orbital Art in the Age of Internet and Space Flight: From Terrestrial to Orbital Perspectives with a particular focus on German artist Achim Mohné

by Pamela C. Scorzin

The Medium Alone is Not Enough: An Archaeology of Diffused Entities and Illusory Spaces

by Katarina Andjelkovic

Figuring out the Female Presence in the Arts

by Carol Lina Schmidt

Mass Culture, New Capitalism, and Its Codes by Waldenyr

Caldas

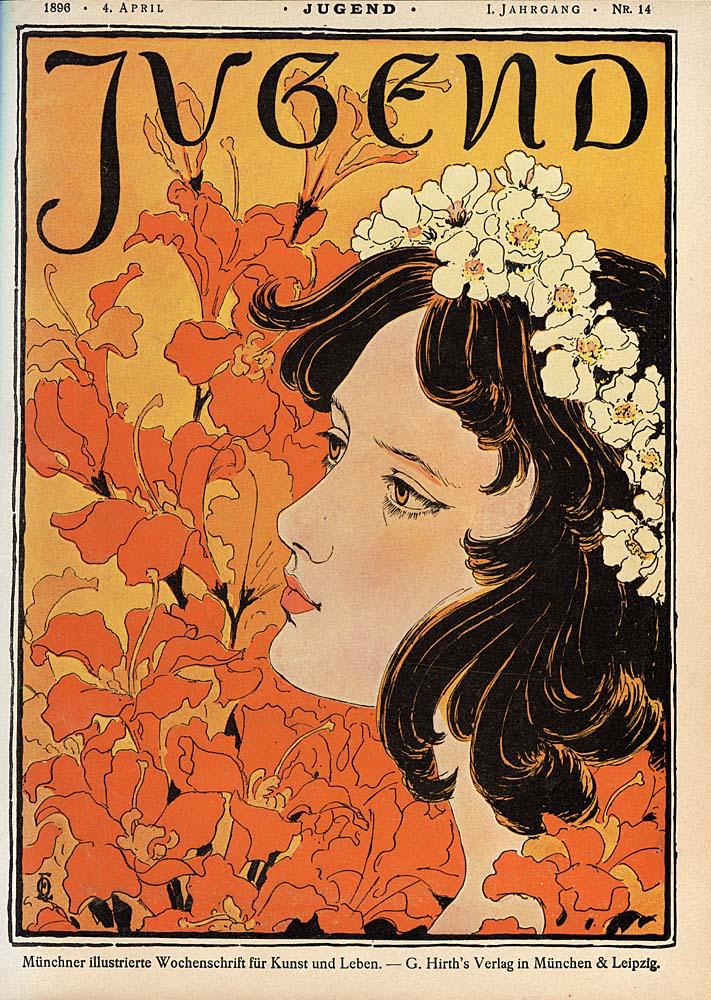

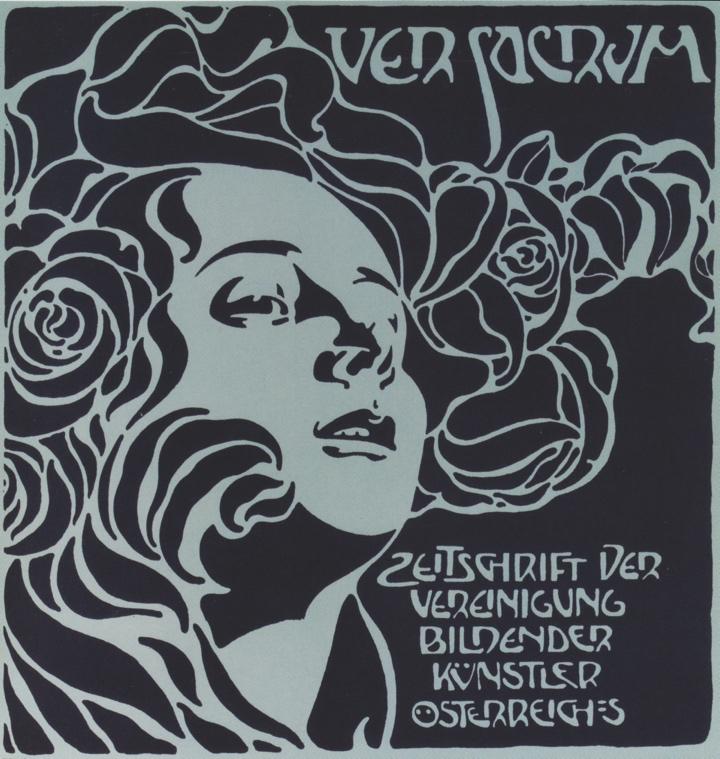

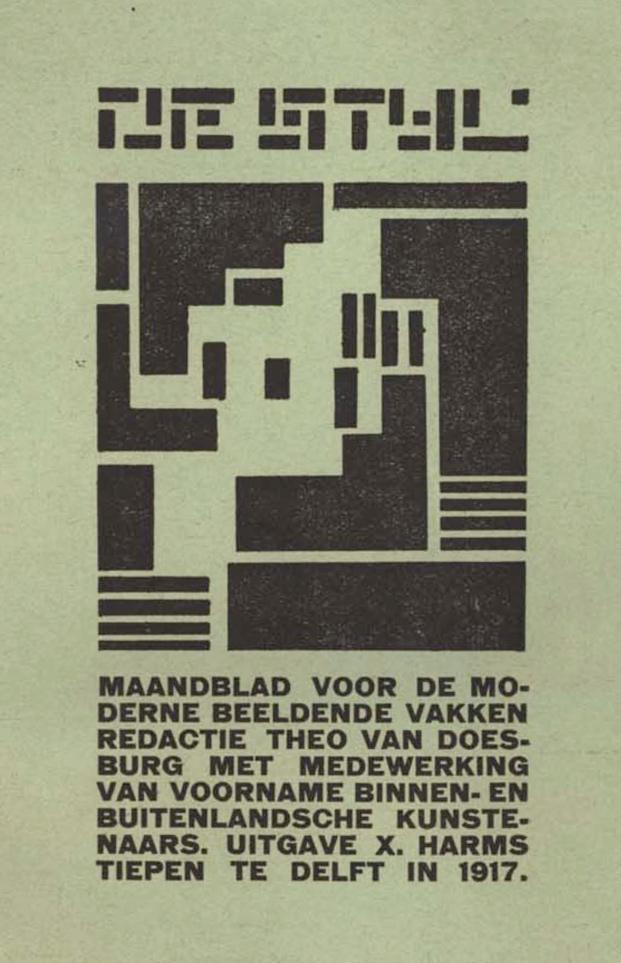

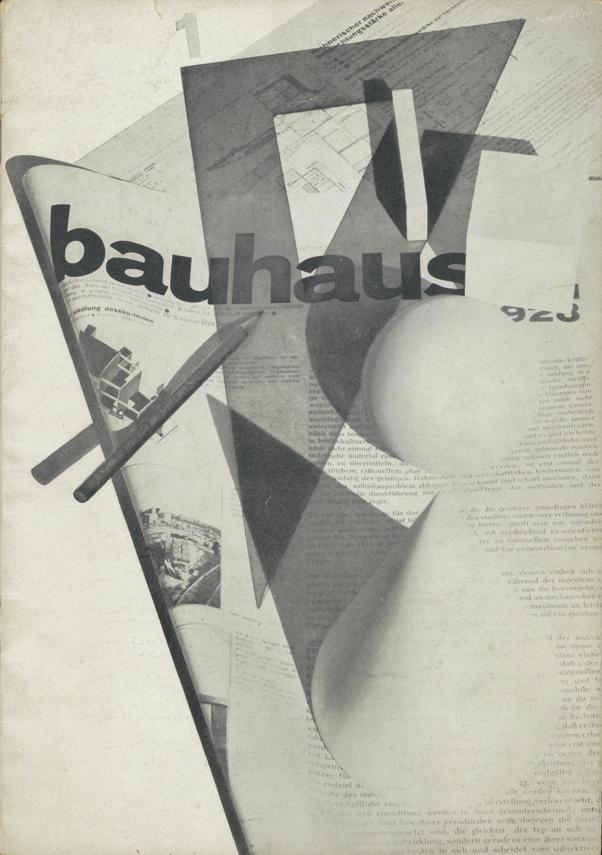

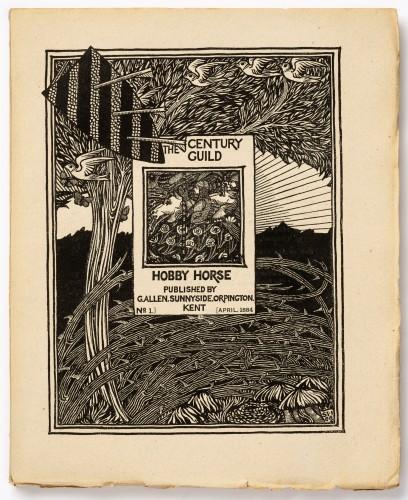

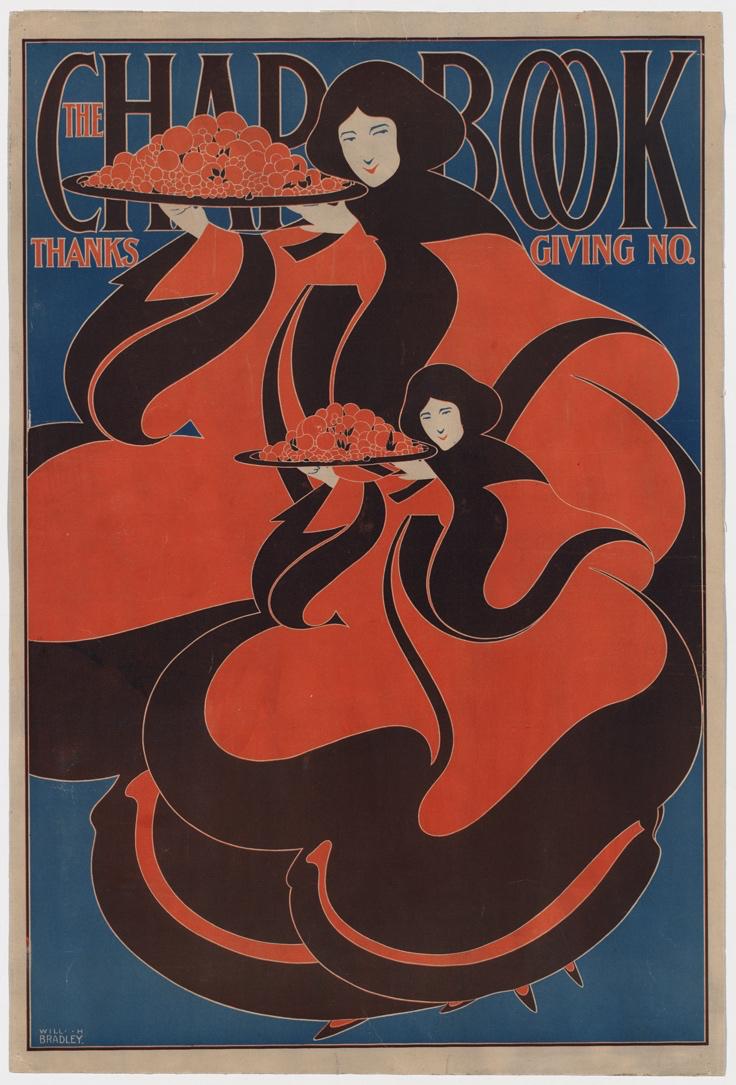

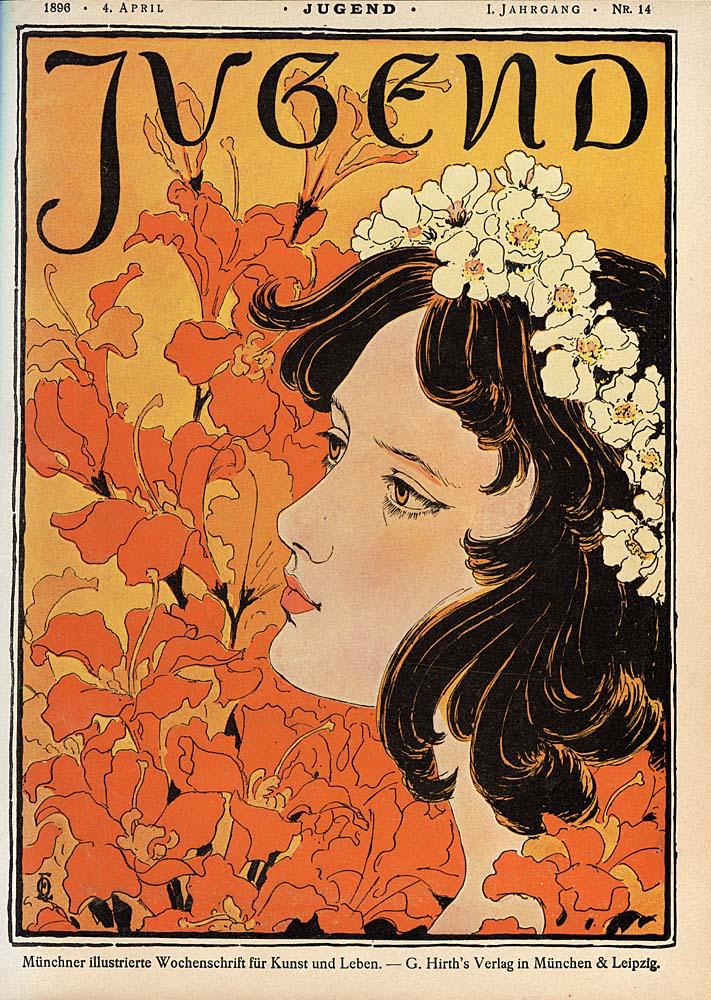

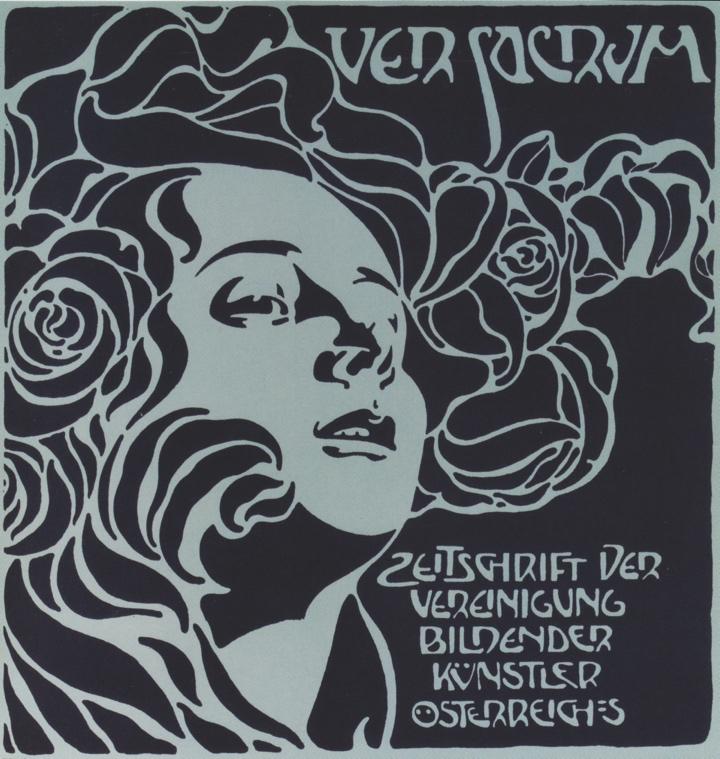

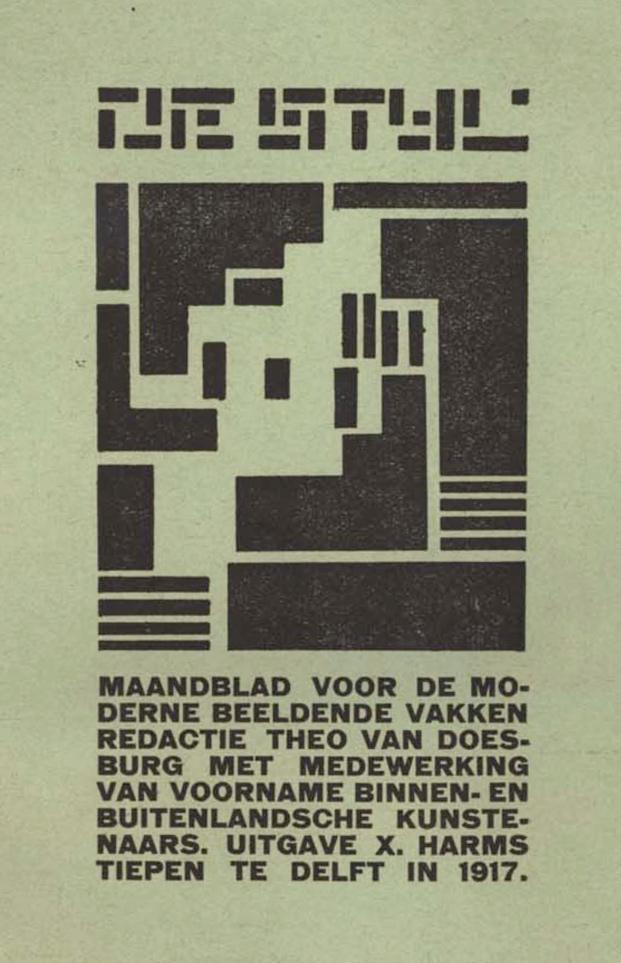

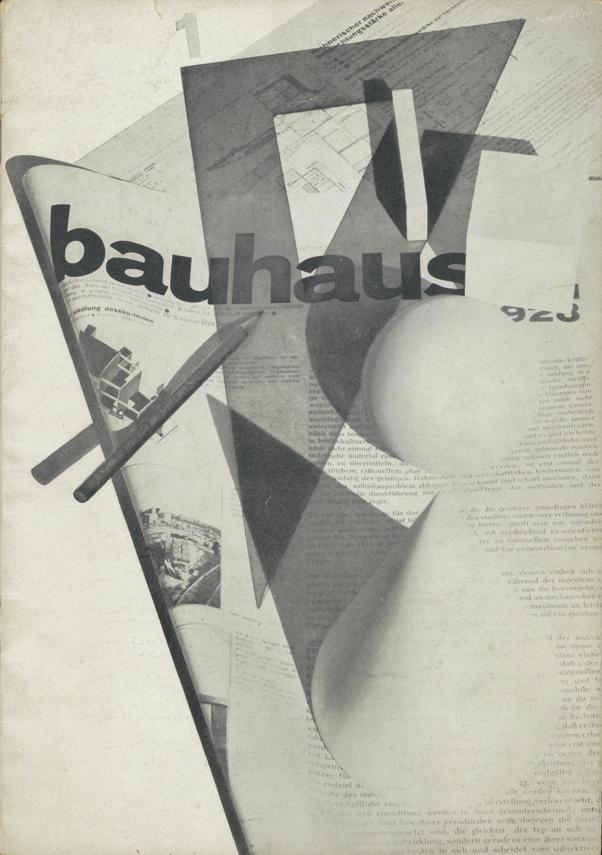

The Democratization of Art Media and the Art of Publishing on Art by Christiane Wagner

Information Submission

Peer-Review Process

Author Guidelines Terms & Conditions

Editor’s Note

Dear readers,

Let's celebrate the first anniversary of the Art Style Magazine!

Since its first edition in March 2019, our Magazine has strictly maintained its periodicity, publishing articles by renowned researchers and professors, as attested by the previous four volumes available to readers, whether linked to the academy or not. Indexing the Art Style Magazine is just a matter of time. As we know, to have our magazine indexed, most databases require one or two years of publication. We are strictly following the procedures required and essential to the indexing process. Regardless of the quality of articles published, analyzed, and discussed at international conferences, we are very attentive to the formal issues in achieving our objective that is, to index Art Style Magazine. Thus, we will continue with the same rigor on the necessary protocol for that to occur, i.e., maintaining clarity of information about the journal publication criteria.

Art Style Magazine is not just another publication among many in this field; it is a medium with its own characteristics, through which the arts and cultures shape its content and connect with a broad audience of readers around the world. This connection is due to the engagement of our editorial team and scientific committee, through social and academic media, presenting a vast number of readers with our first four online editions. Across the entire year, the traffic on our website has reached 9,426 views and 2,460 visitors, and the Issuu statistics show 1,124 reads and 27,278 impressions. And, look at that. We are not even in the index database yet! However, our campaigns have grown this number with each edition, and the result is our anniversary gift the growing interest of a broad audience, including the academic community, for the ideas, reviews, and research results published by Art Style, Art & Culture International Magazine. It is a surprising and even more stimulating result for a magazine that shows itself to be increasingly academic without losing the quality of the graphic design of its editions, something that seems simple when we see it published. However, one thing is sure: without all the technological advances that we have available, it would not be possible. Besides, considering all the difficulties of the analog era, which I know well, it is perfect to have all this software and social media available for spreading arts and culture worldwide!

Additionally, the art of publishing, especially in the academic field, must commit to knowledge by disseminating and contributing to the democratization process and supporting unrestricted access to science. Art Style Magazine supports this cause and remains very distant from the definition of “predatory journals.” Quite the contrary, publishing in Art Style Magazine is free of charge for anyone. There are no article processing charges or other publication fees. There is no copyright transfer toward Art Style Magazine, and the authors hold the copyright and publishing rights without restrictions (see Art Style Magazine’s Terms and Conditions). Our authors, as well as our scientific committee, are renowned professors and researchers willing to support this initiative Art Style, Art & Culture International Magazine.

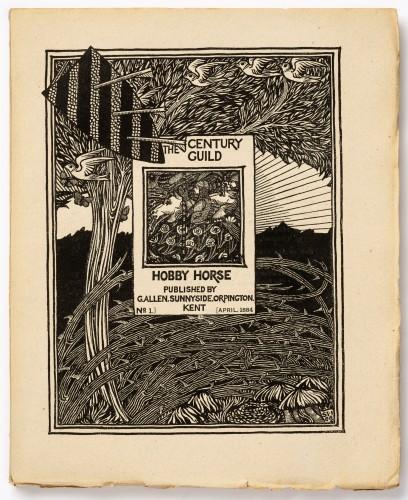

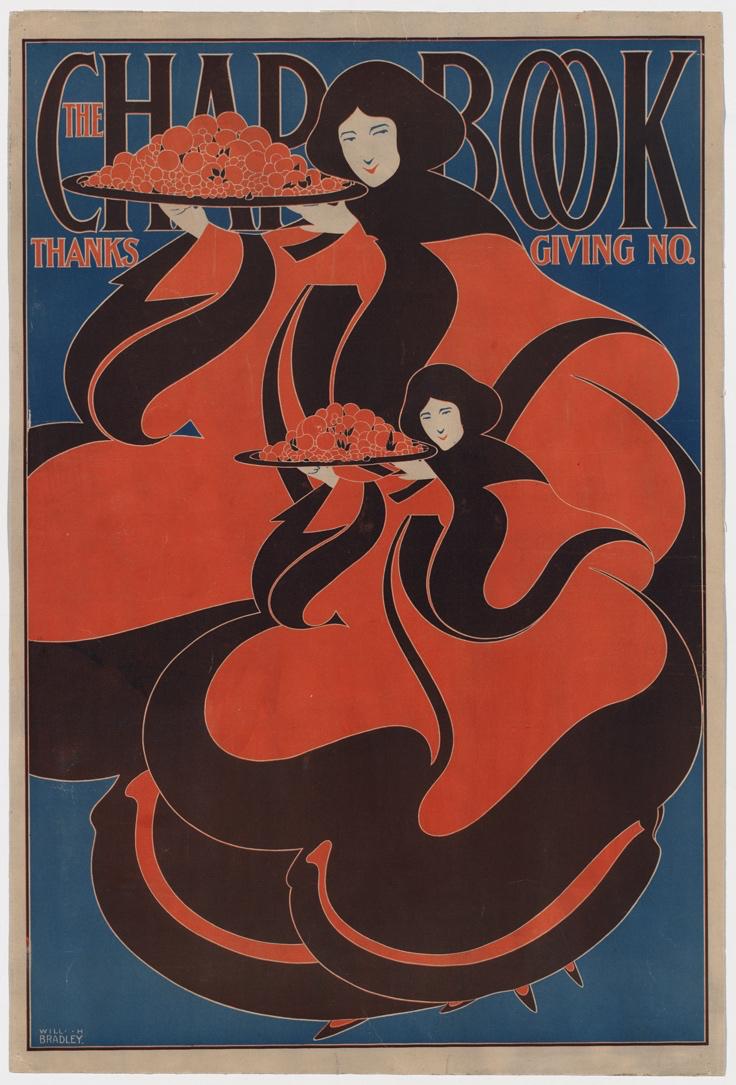

In Art Style Magazine's one-year editions, in addition to the challenges and achievements reported above, I reflected a lot on the craft of publishing and the contribution of that craft to the democratization of culture and art. I thought not only of the precursor techniques but, specifically, the origin of a vehicle that deals mainly with the arts and cultures, of space for sociocultural criticism. What were the stimuli, challenges, difficulties, achievements, and successes of the notable names that opened the door to this art of publishing?

Thus, seeking answers regarding the history that in part belongs to all of us interested in spreading knowledge of art and culture, I wrote, as a conclusion, the article “The Democratization of Art, Media and the Art of Publishing on Art.”

Firstly, thinking about the magazines’ celebration, we present one of our favorite subjects in the arts: the discussion of “good taste,” its meaning in space-time, its cultural and market value, and, aesthetically speaking, what is ugly or beautiful. However, in the face of a general audience, taste is still discussed, and beauty is questioned. To this end, we celebrate our anniversary edition with Jeff Koons’ Celebration series, Tulips (1995–2004) on our cover, supported by Mathias Rithel's article, “Be Tasteful! Be Kitsch! A critical analysis of social standards of beauty.”

In addition to these aspects that are always present in the socio-cultural context, new interests currently dominate the art scene. It is contemporary digital art questioning what is visible and what is not visible. The focus is cyber control, the commercialization of the use of satellites and camera drones, and, even more, the live observation of the planet. Something even further, to our knowledge, is the article by Pamela C. Scorzin, “Orbital Art in the Age of Internet and Space Flight: From Terrestrial to Orbital Perspectives with a particular focus on German artist, Achim Mohné,” which takes us on this journey.

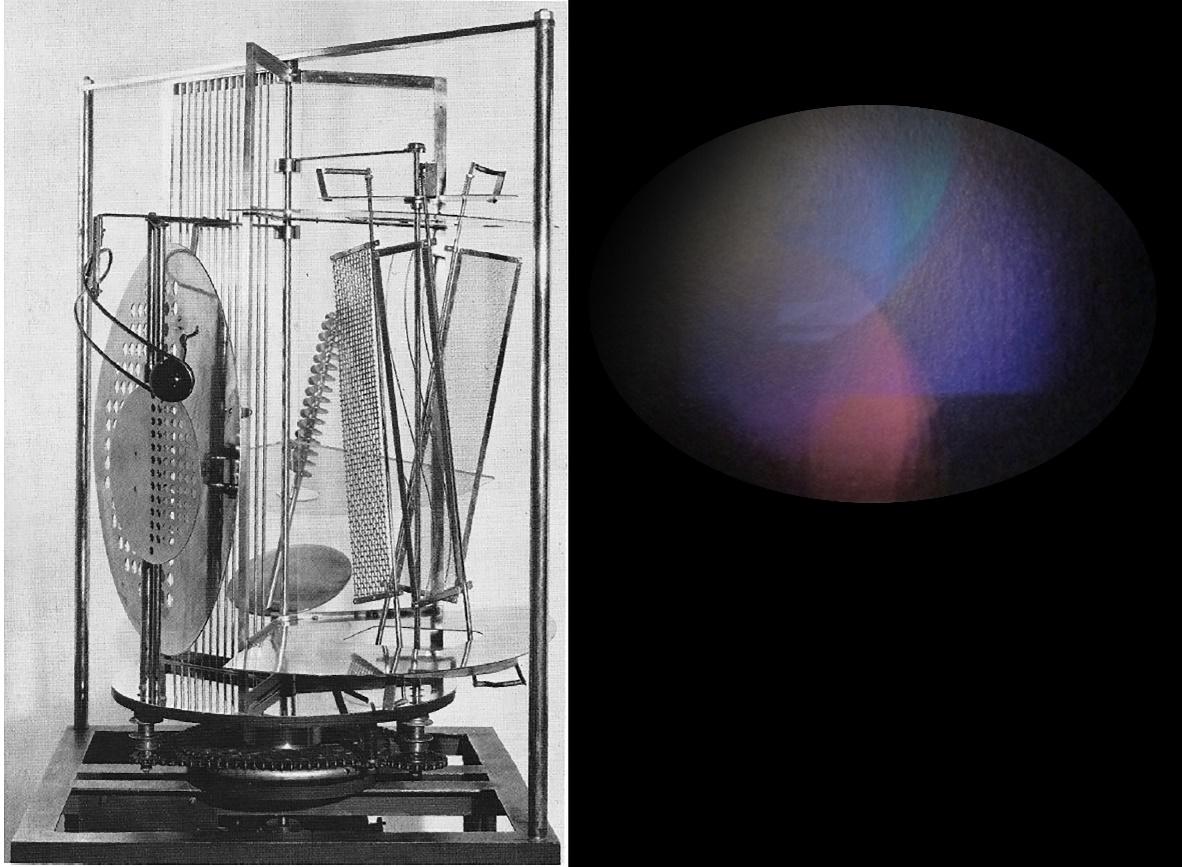

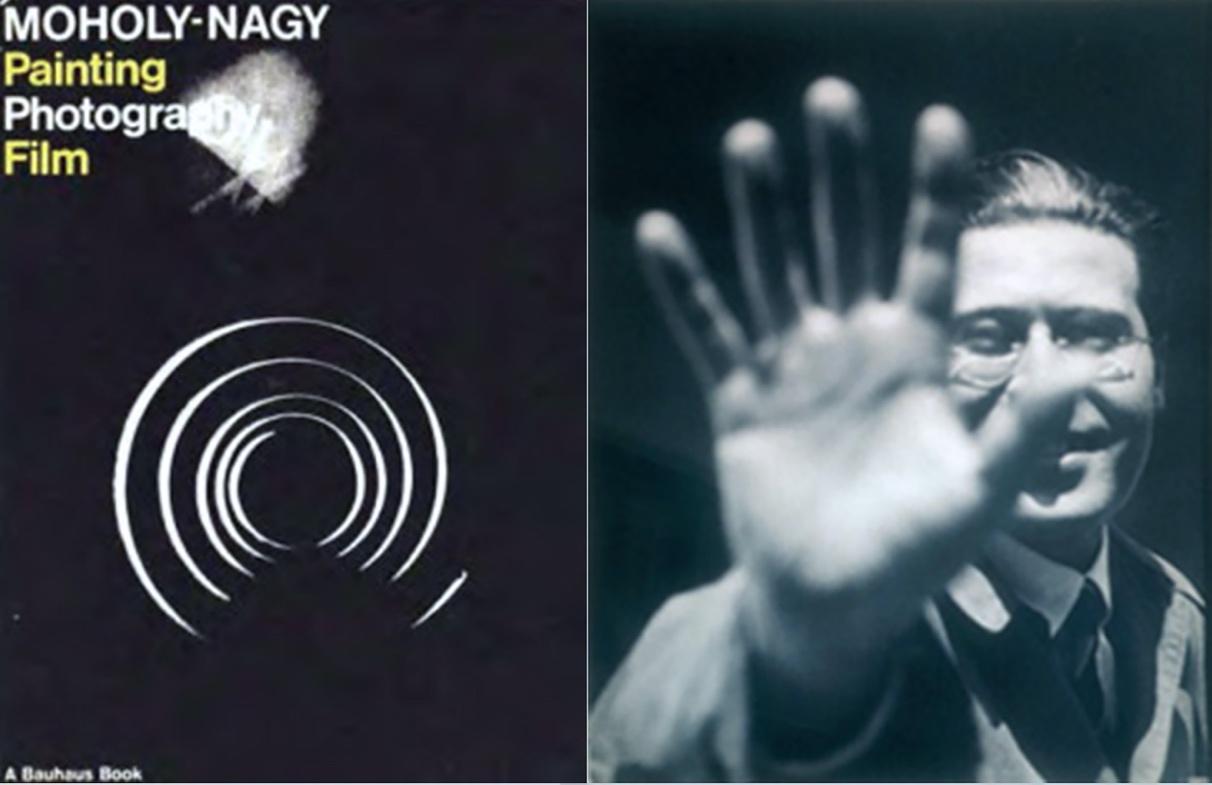

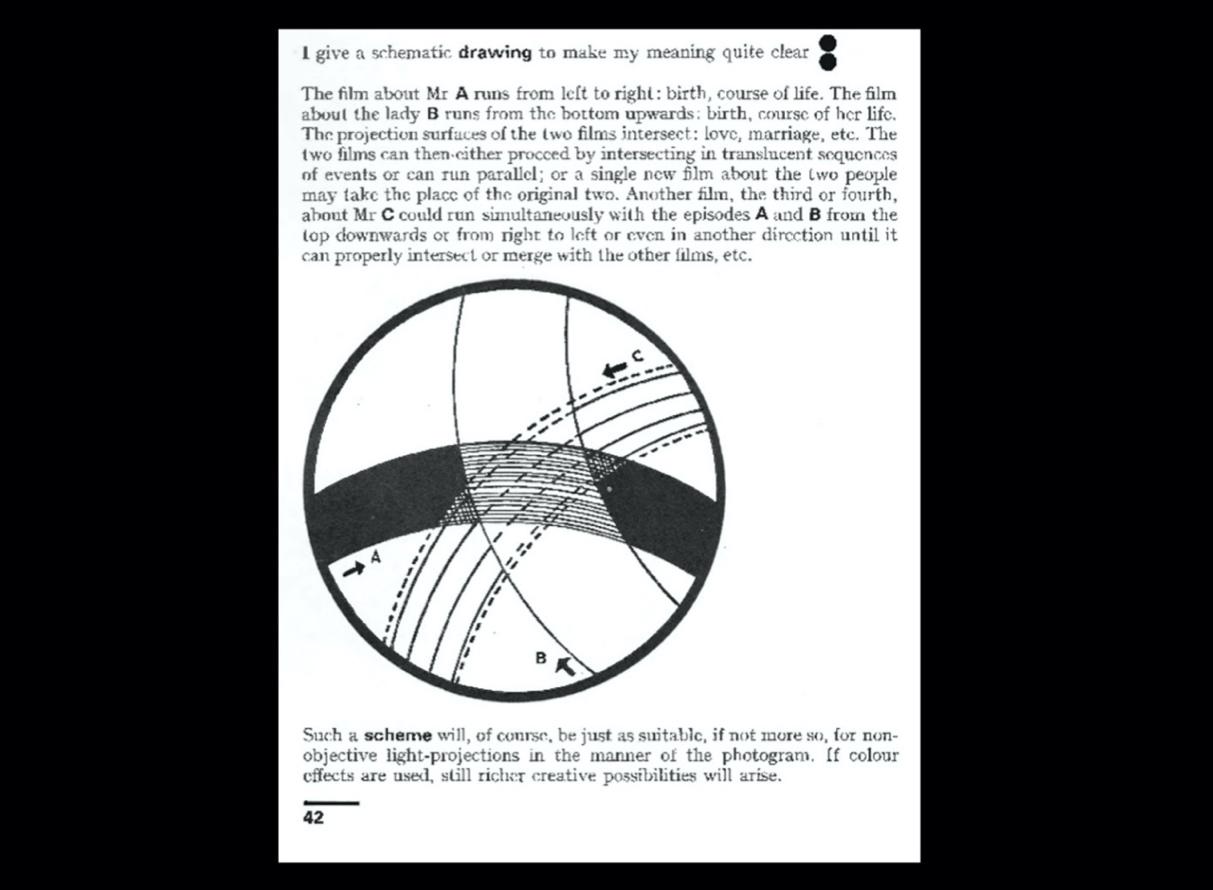

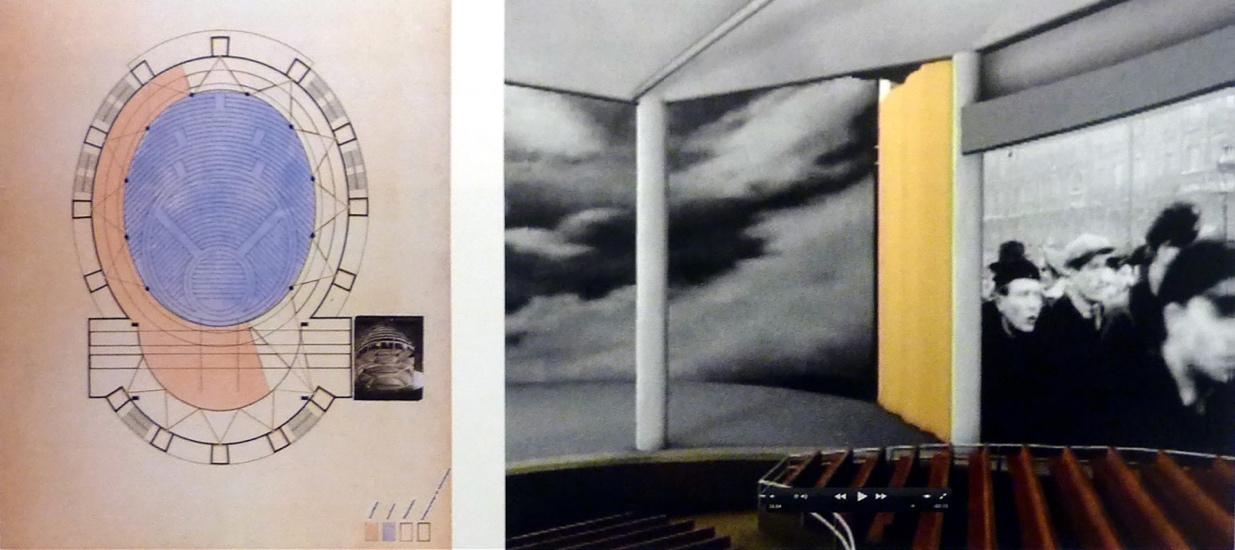

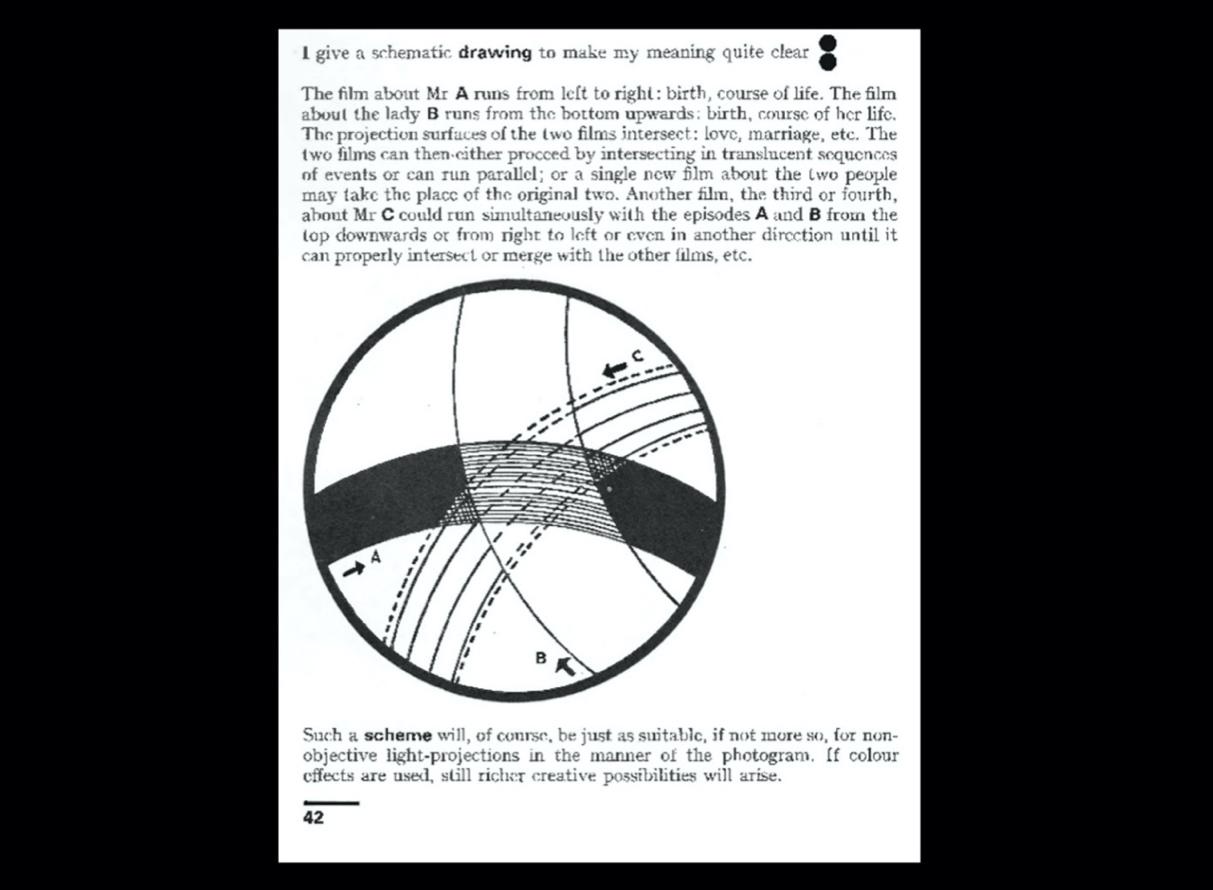

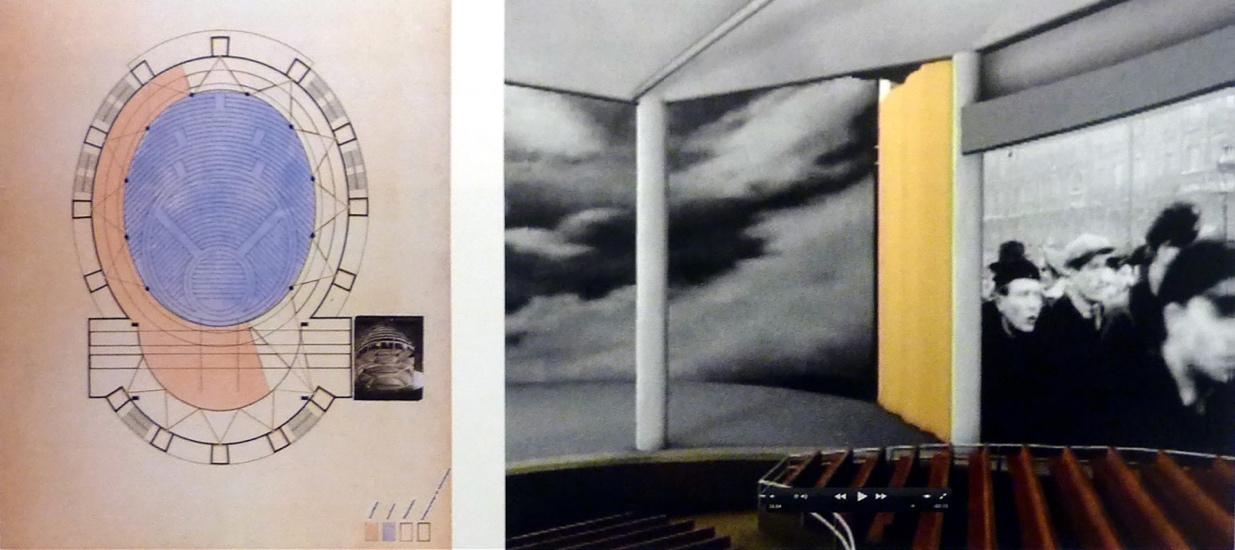

Moreover, without a past, we cannot imagine and build our future or maintain this path of technological innovations. Therefore, we included contribution of Katarina Andjelkovic, who discusses the transformative impact of ancient technology on the medium. In her article, “The Medium Alone is Not Enough: An Archeology of Diffused Entities and Illusory Spaces,” she contextualizes the problem of the medium (space, light, and time) in the history of surface projections. She also explores how projections structure the perception of space, challenging the notion of materialism concerning the medium.

Finally, to close out our edition, we are pleased to present readers with significant essays. One such essay by Carol Lina Schmidt, “Figuring out the Female Presence in the Arts,” will come next, followed by “Mass Culture, New Capitalism, and Its Codes” by Professor Caldas, which describes substantial contributions to the Western culture by Marshall McLuhan, Richard Sennett, and Jean Baudrillard. As such, we highlight an excerpt from Caldas’s opinion: “The three authors mentioned above, in my opinion, have a connection and ideas at the same time, an in-depth, entirely convergent reasoning analysis. Their reflections, each in their way and starting from different themes, give us a reasonably accurate view of contemporary society.”

Thus, we conclude our anniversary edition, with my essay and many expectations, as this edition also marks a new stage; it is the first edition of a new year with many achievements.

Cheers, and enjoy your reading!

Christiane Wagner Editor-in-Chief

Be Tasteful! Be Kitsch! A critical analysis of social standards of beauty

Waldenyr Caldas

Abstract

For a better understanding, this article seeks a more precise delineation of the differences, in the broadest sense, of these two qualifying adjectives "tasteful" and "kitsch " Thus, we must consider social, economic, and cultural barriers and the ever-present class prejudice. Without a social analysis, this kind of criticism would be impaired and, by extension, superficial. We can already see that many obstacles separate these two concepts, and the difference between both terms shows a social border. By analogy, the concepts that separate these two terms can therefore be understood, not just a limit. This separation, it seems, is much more identified with a border the outer edge of something than a barrier a structure that bars passage. It would be naive to deny or ignore this conceptual tension between "tasteful" and "kitsch," although there is a stratified consumption of cultural production. The capital society, always very smart and consistent with its origins, can deal with this stratification. In this sense, a way is sought to satisfy everyone, maximize profits, and keep the status quo unchanged, which has been the logic of Capitalism since its origins and, therefore, nobody denies it. Agreeing or not, with its political-ideological practices is another issue on which we have the free will to accept it or not. This frontier has been consolidating and, at the same time, become a recurrent theme of academic discussions, mainly due to the subjective aesthetic criteria of judging an artwork, qualifying a design, or choosing a musical concert or piece of clothing, among other things. This article mainly embraces the dichotomy created over time about these two terms and its social meaning.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 11

Aesthetics and Politics

We begin our analysis with a matter of extreme subjectivity, which necessarily involves the aesthetic values of class culture. Loosely and with possible exceptions, it is almost always dogmatic content analysis that is read, seen, or heard. Being kitsch is tasteless, and being tasteful is suitable for cultured and refined people. This affirmation is a syncretism that places modest products of mass culture and popular culture as something of the subaltern classes alone. Indeed, this attempt at such fusion is accurate, and there is a logic to it, although not as precise as it may seem. The cultural industry stratifies its production precisely to reach the consumer market of all social classes. Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer (1947), in their well-known analyses of "the cultural industry" in the humanities, have already taught us that the masses are not the measure, but the ideology of the cultural industry, even though the latter cannot exist without them. Empirical observation of the facts makes it current, as long as one thinks of the society of Capital, where the ideology of profit and the masses become inseparable and interdependent. The syncretic misconception, however, is the aesthetic evaluation (sometimes also political) that some critics make of these products.

Its consumers are almost always of low income, low education, with restricted repertoire, a low level of information, and residents on the periphery of large and medium-sized cities. This model is almost a standard of the analysis and reviews that we see in journalistic texts academic as well when we think of art criticism, whatever its origin. In this sense, the syncretism is always present. For these reasons precisely, the aesthetic evaluation of products aimed at the subaltern classes or produced by them, with very few exceptions, is always very unfavorable. These products are considered unimportant and of dubious taste at least. But, this facet is only part of the question. There is another, which, in my view, is even more critical. The "aesthetic" analysis of these products is always full of qualifying, repetitive, innocuous adjectives that, strictly, say nothing or almost nothing.

Some of them seek, among other things, to analyze the possible politicalideological content of the work, as if the author had an obligation to publicize their political engagement, their option for a political ideology. Often, this approach has the background and objective of establishing a serious tone and depth to the analysis. In Brazil, in the face of a troubled and broken political trajectory of systematic authoritarianism, this is very noticeable, even though we have been searching for democratic consolidation since 1985. During the 1960s to 1980s, the

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 12

political and ideological issues were a kind of "aesthetic thermometer" of any cultural product. To be respected, artists would have to declare themselves and engage politically by showing the ideological profile of their artworks. Then, by most of the criticisms, their artworks were considered good. Now, we all know that aesthetics and politics have always been pari passu, but not exactly in this way

An artwork may incorporate profound political-ideological issues, but that does not necessarily mean that, because of this incorporation, it is of good quality, which is a mistake mainly because the issue of the quality of work is something much more complicated than it may seem. Thus, but not only, these evaluations are almost always empty text. An attempt to explain the quality of the work aesthetically, but without any substrate or upholstery, is something notoriously sterile. In other words, reading or not reading this assessment would be almost the same. The readers leave the text as if they had not devoted their time to reading.

It is necessary to understand, for example, that when Pablo Picasso made Guernica, he intended to denounce and protest against the arbitrariness, violence, and horrors practiced in this city in his country. The Nazis were ruthless. However, it would be unreasonable, I think, to expect that visitors to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where this artwork remained for a long time, see Guernica for the same purposes and with the same criticality as Picasso. Many museum visitors want to know the artwork itself without worrying about its political-social significance.

This approach, of course, does not mean alienation. However, this aesthetic experience may or may not, in some cases, emerge at the time of the visit, depending on the viewer's repertoire. Knowing an artwork of the magnitude of the Monalisa, Guernica, and others is already something pleasing to the visitor. Thinking about its socio-political relevance as the author did at the time of its creation is an attitude, a very personal option for its visitors. It is known that great works are almost always disputed by people for their mythical figure and iconic character, understandably so. The crowd that annually visits European, American, and Asian museums, among others, is not interested in or simply does not know the history of that artwork. They do not know how artist arrived at the result displayed in the museum. With some exceptions, this view is limited to specialists and scholars of the arts, which is the prevalence.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 13

Toward Kitsch Art

The aesthetic concepts used by professionals in the analysis of any cultural product could have more precise and explicit arguments and theoretical foundations. The reader must objectively know the reasons why the critic refutes a specific artwork and places it on the level of the artwork of "dubious taste." But after all, what are the objective criteria that led the critic to assign that work an uncertain status? This objectivity strictly does not exist, and the whole argument is lost at the level of subjectivity. Prevailing in the preparation of the aesthetic evaluation of criticism, the individual critical opinion in the absence of more consistent arguments chooses the path of "wishful thinking," which is the most modest empirical way of making a qualitative assessment (if possible) of artwork when there is neither theoretical resources nor an adequate and sufficient repertoire to do so. In the absence of these elements, the critic, consciously or not, uses a resource and strategy terribly similar to that of television presenters. It is the so-called “factual function” of language, as the French linguist and semiologist Georges Mounin explains in his work (1974). He says that for the factual function, the language seems to serve only to maintain among the interlocutors a sense of acoustic or psychological contact and pleasant proximity for example, in social, hollow, or loving talk wherein nothing is said

Apart from matters of love, empirically, the presenters of television programs make use of the phatic function of language. They need to speak without interruption when they are not showing the planned attractions in their programs. If they do not, there is a severe risk that the viewer will change channels due to a lack of motivation in the program itself. The viewer loses this dynamic due to the absence of gestural stimuli, so crucial in the process of mass communication and dialogues with audiences. It should be noted, however, that the program presenters are not making any aesthetic evaluation of any product. They are merely doing their television work. If they use it consciously or not, the phatic function of language is another issue that could undoubtedly be the subject of further study. It does not seem to be the right or correct option to leave thinking about “aesthetic quality” under the responsibility of this intelligentsia. Consequently, merely accepting that it establishes within its criteria and knowledge what is of good quality or beautiful is, in short, a judgment of taste that implies the quality of a product, an artwork, a handcrafted piece, and more. In this case, all the educated and specialized people in their respective areas would have the intellectual authority to establish the criteria for the aesthetic taste of any work related to their métier.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 14

However, it is not exactly this. It is not correct (and perhaps not even fair) to attribute to educated people even with a solid academic background and specialized in the arts, for example the ability to determine what is beautiful, artistic, good taste, dubious taste, or even distasteful. If so, we would be sanctioning an authorization for educated people to dictate the rules and criteria of what is considered beautiful, of good taste, and good aesthetic quality. I do not think this approach would be the best thing to do, because situations like this have already produced great mistakes and will undoubtedly continue providing them An example, in my view, quite enlightening to this issue is the following: Initially, it was registered in the work of Stanley Edgar Hyman1 (1948) but was carefully interpreted by Professor Antonio Candido2 in his work (1978). In 1837, Liszt gave a concert in Paris, which announced a piece by Beethoven and another by Pixis, an obscure composer already considered of low quality. Unintentionally, the program changed the names, attributing the work of Pixis to be from Beethoven. The audience applauded Pixis thinking it was Beethoven and disqualified Beethoven thinking it was Pixis. Cases like this one are not unique, and scholars of art and literature, from time to time, record cases similar to what happened here.

It is quite likely that a person who is cultured, sensible, and with a more refined degree would refuse to make any aesthetic judgment as if its result were something definitive. However, it would not happen. They would do it knowing that their evaluation is only one among so many other meanings in the face of subjectivity and aesthetic values. Therefore, in fact, it makes no sense for the art critic to label such an artwork as kitsch while exalting another artwork as excellent with complimentary adjectives. Collectively that is, for the public criticism does not contribute at all. Individual experiences have their importance and contribution in the field of cultural criticism, there is no doubt, but they cannot be extended to a universal participation and acceptance. No evaluation, no objective principle of taste is possible. There are many subjective factors that interfere in the faculty of judging and creating means to justify what is beautiful, forming a judgment of taste. But there may be some affinities between the art critic and a select group, even taking a universal dimension to like an artwork or not

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 15

At first, one has to think about the following: if we analyze an artwork, or merely a street event that we witness, we do so with our repertoire and knowledge of our class culture. This is understandable and would happen spontaneously, mainly because we do not know enough about the culture of other social classes and their respective strata, hindering a more in-depth analysis of the cultural ethos, its intricacies, and subtleties of everyday events, which could compromise, among other things, the quality of empirical information on the artwork. This limitation would be enough for us to understand that it is not possible to carry out a more in-depth analysis, and, more than that, we would certainly not feel comfortable doing so. Empirically, it is easy to understand this issue, and the examples seem to be quite illuminating. Think of one of them: a young worker leaving the industry at the end of her workday looks vastly different from the president of the company. The difference in socioeconomic level, educational background, and repertoire creates the values and judgment of different tastes.

With some exceptions, this becomes visually perceptible, not only in the appearance revealed by their clothing but also in their personal adornment. This entire set of seemingly unimportant factors shows the differences and aesthetic conceptions of class cultures and, of course, of socioeconomic level. Under these conditions, therefore, the concepts of kitsch and tasteful could be misused, as almost always happens, moreover, with a powerful charge of social prejudice. It Is, above all, a matter of citizenship, respecting the class condition without an aesthetic assessment of who is kitsch or tasteful, based merely on the subjectivity of an isolated opinion and without theoretical support. Thus, even with distinctive visual evidence between the worker and president of the industry, it would not be possible for us to say that the aesthetic taste of one is superior to that of the other. This attempt, most likely, would lead its author to make conceptual errors in search of positive results that would undoubtedly be imprecise and full of redundancies and innocuous and unnecessary words for their explanations, as always happens. The factual discourse on the aesthetic evaluation of cultural products is always full of adjectives that clarify little. And what we have seen so far not only occurs with so-called tacky or old-fashioned products. Everything is repeated precisely the same way for the evaluations of products considered in good taste. In the arts, for example, products of tasteful people are predicated on words that say nothing; the logomachy, factual speech is also present, just set up to a degree of greater

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 16

complexity, while the speech goals are the same, valuing the product and making it as profitable as possible, even if it uses logomachy discourse. There are exceptions to be considered, but it is not unusual to have an unofficial partnership between the entrepreneur of the arts and the art critic, in the sense of providing greater visibility and seeking to value an artwork so that they will be well quoted in the art market.

Thus, the art critic, through the media, must create the image of an artist and artwork of special relevance. With this agreement, the art critic transfers his or her prestige (if he or she has some) to the artist and unofficially fulfills what was previously agreed with the entrepreneur of the art market. Under these conditions, the quality of that artist’s work is not discussed, even subjectively. What is on the agenda is another matter. There is interest where marketing overlaps with aesthetic evaluation, though when the artist has no talent, it requires a set of words, a critical speech in the criticism writings, testimonies, or other forms of communication. Such “talent” can indeed be manufactured in the media as it occurs in all segments of the arts. Now we return to a central question in this article: how to justify an artist's talent, if not with personal and subjective opinions about their artwork and, therefore, open to doubt? This is a question with answers that remains unsatisfactory. In a Capitalist society, often, having talent is not enough for the artist to receive recognition for their artwork.

The term “kitsch” that is used to disqualify is also understood as a means by which the “substitution” of values shows the viewer simpler forms of perception and interpretation (and this offers greater emotional strength). In this sense, what is the need to make a highly intellectualized analysis of the work of art, if the person who makes it only offers his opinion and nothing else? Well, this does not mean that they are right or wrong in their aesthetic concepts; they are solely giving opinions. It also does not mean that the analyzed work is an excellent artwork or a kitsch one. There are no universal taste standards, and there is an internal taste logic that differentiates aesthetic taste between different social classes. And this, of course, does not mean that a social class has a more refined aesthetic taste, more sophisticated than the other. It just means they are different and nothing more. Even the taste for classes also differs internally between people. If, for example, a person with a rather modest repertoire is dazzled by Demoiselles d'Avignon, and

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 17

another viewer with a solid intellectual background falls in love with Jeff Koons's sculpture Tulips, undoubtedly the “status” of both will remain the same. Pablo Picasso’s artwork will maintain its prestige as a great work of art as for being the first cubist painting, while Jeff Koons’ sculpture Tulips will retain its “status” as consecrated work by the general public.

Indeed, the set of artistic works by Koons has a very critical purpose, as Professor Christiane Wagner shows in her article entitled “Kitsch, Aesthetic Reminiscences and Jeff Koons” (2016). She explains that Koons has been collaborating with the public’s self-esteem through his artworks, destroying guilt or shame in people who, in their banalities, immerse Tulips sculpture seven tulips of varying colors fabricated from mirror-polished stainless steel is part of the Celebration series, in particular reports the day-to-day aesthetic values added to the celebration symbols. Moreover, Koons also emphasizes these common aesthetic values with another sculpture series called Banality that sets the kitsch as the high motivation for the audience.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 18

Sculpture Tulips (1995-2004) by Jeff Koons. Photo by Pawel Biernacki. June 10, 2018. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Aesthetics of Imposture

We are here in the face of what we might call, for lack of a better term, an “aesthetics of imposture,” because of logomachy discourse as an artifice that consists of presenting subterfuges and arguments that are not true and, thus, an imposture. Certainly, this is not an intentionally artful language, which would be unacceptable. It seems to be, rather, the lack of objective arguments to better spell out the aesthetic values of the work. This lack is quite common among socalled art critics without the resources to make their opinion explicit.

However, this art criticism may not exist as universal participation, but only as subjective judgment. Aesthetics is part of the philosophy that reflects on art and beauty. All the literature in this regard does not propose, approve, or accept consolidated judgments. In the Platonic sense, there is a reflection on the absolute beauty in aesthetics, or in the Kantian sense for the universal taste, but there is no unanimity among thinkers in aesthetics. Among them, we highlight Hegel, who is opposed to both the Platonic and Aristotelian senses. He instead considered the principles of the relationship between form, sensitive, artistic achievements and content, the idea, in a process of synthesis and evolution of the spirit as a historical moment. Therefore, art Is part of a historical and cultural context. In this path, it is considered that the art's meaning is related to time and culture as well as social class. This approach is one of the largest problems of art criticism.

Exceptions aside, when critics make their aesthetic assessments of taste and the idea of beauty, it is as if they are talking about a universal truth. However, there is no replica of their text. Their words reverberate strongly with the public, as if it were, in fact, a universal truth. Thus, this criticism can consecrate a specific artwork, creating an “untouchable aura” of the ideal of beauty and quality about it or destroying it by labeling it as inferior quality or of a dubious taste.

This discussion aligns with some illuminating observations made by Immanuel Kant (1790), precisely because this thinker analyzed taste and beauty from the perspective of objectivity and subjectivity. Kant argues that there is not an objective taste that determines by concept what is beautiful because every judgment, itself, is aesthetical as such, it is a perception that determines the motive and the subject's feeling and not the quality of an object. Thus, the search for a principle or general criterion for beauty and taste through certain concepts is senseless since what is sought would be impossible and contradictory in itself.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 19

Kant's lessons lead us to believe that art critics who use factual discourse do not know these lessons, have forgotten or misinterpreted them, or at least have not yet read them. Instead, the reader receives elusive explanations that cannot be sustained with a closer reading. Now, if this is something partially or entirely intentional, this approach creates is another situation. Each case must be viewed and analyzed separately, avoiding injustices. Therefore, it is necessary to understand that responsible criticism does not act in this way.

In any case, the dichotomy that I mentioned at the beginning of this article prevails. The product of educated people is also seen as tasteful by much of the population, especially of the more modest strata, but not only. This is the ground to be protected by an "aura" that exerts a psychological influence of respect and admiration in people, even by the combination of these two adjectives.

There are two aspects to be highlighted for specific segments of society to reach these concepts mentioned above. The first is the ignorance, or almost, of the cultured people's products. The second is a little more complex and depends on the socioeconomic status of each social class. The subordinate classes, or at least some segments of them, tend to mitigate and psychologically revere the consumption of the so-called more affluent social classes, precisely given the considerable difference in purchasing power between them. This is the “aura” that I referred to earlier.

To illustrate empirically, it is worth mentioning one example, but there are many others. In São Paulo, the Municipal Theater, located in the so-called old city center, keeps an intense program of musical concerts and other cultural events every year. On show days and just before the start, while people are arriving, there are other people on the sides of the entrance door who, most likely, pressed by economic scarcity, look respectfully at people entering the Theater. It is the curiosity and natural desire of a notoriously modest audience who could hardly buy tickets to attend a musical concert. It is not about homeless people (these appear in small numbers), but about people who have not had the opportunity to see a "tasteful" show full of cultured people. But at this point, if any of those people wanted to come to watch the show, it would not be possible if it were not with ticket in hand. In this case, there is no alternative but sublimation or to seek other forms of entertainment and social interaction. As known, sociability in large cities, although essential for all of us, is something a bit more complicated. This topic is not part of this article, but it is worth reading David Riesman's work, The Lonely Crowd (1961).

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 20

But everything does not always happen as described above. There are situations in which the so-called kitsch and tasteful products come to have a close and pleasant view. In São Paulo (not an exception), the government sometimes organizes free shows that include the presence of artists highly considered by the cultured public and the specialized press. It is worth remembering, as an example, the outdoor musical concerts in Ibirapuera Park, which in those moments becomes a democratic space. On these occasions, the public is undifferentiated because it contemplates all social classes and their respective segments; thus, the concepts treated here are irrelevant. This issue of kitsch and tasteful goes unperceived precisely because it is unimportant, but also because the people who are there at that moment come willing to participate without worrying about these irrelevant and imprecise aesthetic issues. This audience is presently interested in leisure, entertainment, not dwelling on subjective aesthetic evaluations that explain nothing. It is much better this way. Public parks, among other things, even have the virtue of eliminating at the base this tension between kitsch and tasteful, although visually, the socioeconomic differences between their visitors are realized. It is at this moment that people have the same focus on enjoyment, finally, for recreational pleasure. Fraternization and sociability prevail as something essential, especially in cosmopolitan cities like São Paulo.

Final Considerations

To finish this article, I want to again raise the lessons of the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1790) when considering the issues on the judgment of taste. He says that the unfavorable judgment of others can arouse in us justified reservations about our judgment; however, it can never convince us that our judgment is incorrect. Therefore, there is no empirical argument to impose on anyone the judgment of taste. That is right, perfect! There is nothing more just, more libertarian and democratic, than to respect people’s judgment of taste without any aesthetic bias, especially when we lack solid arguments and fundamentals. This approach is what is routinely seen. It is necessary to make this assessment accurately, from within oneself and not in a protocol way, just to let others know that we “respect” people’s right to like anything kitsch or tasteful.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 21

The Kantian lessons, in my view, should be read by some art critics before they disregard any artistic work. Their opinions and ratings are just more such thoughts, even though each critic considers them as teachings for the public accustomed to the arts. Nonsense. They should be regarded as, of course, exceptions. It is natural, for example, for the art critics to give their opinion. What is not reasonable is that they believe themselves to present the truth and expect their ideas to prevail as a kind of a consolidated norm as aesthetic criteria of an artwork evaluation. This is unwise, much less acceptable. It is a childish narcissism that cannot be accepted.

And, to conclude, I want to register the following: when a work of art becomes public, at the same time, it also becomes subject to the most diverse interpretations. Naturally, viewers experience your reading just from the elements they perceive in the work. Of course, for this, they will be based on their repertoire, their experiences in everyday life, and, above all, their class condition, among other things that, together, will enable them to read the work.

Therefore, we will have an opinion, an analysis no less critical than that of the critic specialized in the subject. If both interpretations (that of the critic and that of the ordinary citizen) are convergent and complementary, the interested public will benefit from knowing the subtleties that a work of art may have. But if they are divergent, there is no need to prioritize the words of the art critic.

After all, it is just one opinion among many others. In some cases, as I already demonstrated at the beginning of this article, the critic's opinion may even be committed to market values, which would be natural because, after all, the work of art is, among other things, fundamentally merchandise, like almost everything in capital society. At that moment, it is very convenient to remember the work of the Italian literary critic, philosopher, semiotician, Umberto Eco, in his work Opera aperta (1962) translated in English as The Open Work (1989). Still, which has crossed time and remains current, he teaches us that any work can enable us to interpret it. The artwork is open because it does not have a single interpretation. It is polysemic, and therefore open to the most diverse analyses. There is no way to disagree with Umberto Eco in his arguments mainly because no model of theoretical analysis can cope with revealing the aesthetic characteristics of a work, but only how to perceive that work according to its assumptions.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 22

Author Biography

Waldenyr Caldas is a full professor in Sociology of Communication and Culture at the University São Paulo. He was a visiting professor at University La Sapienza di Roma and the Joseph Fourier University in Grenoble, France. Professor Caldas has been a professor since 1996 as well as the vice-director (1997-2001) and Director (2001-2005) of ECA - School of Communications and Arts, University of São Paulo. In his academic career, he obtained all academic titles until the highest level as a full professor at the University of São Paulo. Currently, he is a representative of the University of São Paulo, together with the Franco-Brazilian Committee of the Agreement “Lévi-Strauss Chairs,” and a member of the International Relations Committee of the University of São Paulo. Its scientific production records many books published and several essays published in magazines and national and international collections.

Notes

1. Stanley Edgar Hyman, The armed vision (Knopf, New York, 1948) 323-324.

2 Antonio Cândido, Literatura e sociedade (Editora Nacional, São Paulo: 1978) 41.

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor W. Théorie esthétique Translated by Marc Jimenez. Paris: Klincksieck, 2011.

Eco, Umberto. The Open Work. New York: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Kant, Immanuel. Le jugement esthétique Textes choisis. PUF, 2006.

Mounin, Georges. Histoire de la linguistique des origines an XXe siecle. Paris: PUF, 1967.

Riesman, David. The Lonely Crowd. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020.

Wagner, Christiane. “Kitsch, Aesthetics Reminiscences and Jeff Koons,” Revista Visuais, Institute of Arts (Sep 24, 2016), UNICAMP.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 23

Orbital Art in the Age of Internet and Space Flight: From Terrestrial to Orbital Perspectives with a particular focus on German artist Achim Mohné

Pamela C. Scorzin

This is Major Tom to Ground Control I'm stepping through the door And I'm floating in a most peculiar way And the stars look very different today For here

Am I sitting in a tin can Far above the world

Planet Earth is blue And there's nothing I can do

(“Space Oddity” by David Bowie)

Abstract

The shift of perspectives, from local via global to orbital, and back down to Earth again, is fundamental to the concept of the Anthropocene. It is a recently proposed geological epoch dating from the commencement of significant human impact on Earth's geology and ecosystems, including anthropogenic climate change. Contemporary art reacts to these epochal shifts in a variety of ways. It is not only about creating new spectacular views and scenery but rather, in many ways, about basic changes of perception and experience that lead to a new critical awareness and heightened environmental consciousness. Artists like Trevor Paglen and Achim Mohné, among others, are interested in exploring and discussing the increasing importance of comprehensive surveillance systems and data mining by satellite technology and drones nowadays. Sometimes, they appropriate, or they try to hack these new scopic regimes with their artistic rhetorics and aesthetics. For instance, they are smuggling their poetic artworks into the networked systems, or are scrutinizing its unique digital image culture, which sometimes produces strange imagery like, for example, the glitch and digital abstraction. In the end, this contemporary digital art also asks what becomes visible and what remains invisible in a cyber-control age that highly commercializes the use of satellites and camera drones as well as live-observation of the planet. Moreover, in the age of digitalization, picture-taking is everywhere getting more and more automatized, and more and more images are produced as well as generated and processed with the help of orbital satellite cameras with intelligent, deep-learning algorithms nowadays. These are the post-human eyes onto Earth.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 25

On the Shift of Perspectives: from the global to the orbital, and back down to the Earth again

Published: February 5, 2019. Historical Date: February 14, 1990. Image source: https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/536/voyager-1s -pale-blue-dot/.

In the age of globalization, the image of the "pale blue dot" (Fig. 1) has slowly replaced the famous "Earthrise"- photograph (Fig. 2), which had been a global icon of the post-war period as well as the Cold War with its race to the moon. According to NASA, this stellar color image of the Earth globe is a part of the firstever 'portrait' of our solar system taken by Voyager 1. The spacecraft acquired a total of 60 frames for a mosaic of the solar system from a distance of more than 4 billion miles away from humankind's home planet and about 32 degrees above the ecliptic. From the technical sonde's far reach, our small Earth is a mere point of weak light, less than the size of a picture element even in the narrow-angle camera. Our home-planet was a crescent of only 0.12 pixel in size. “Coincidentally, E arth lies right in the center of one of the scattered light rays resulting from taking the image so close to the Sun. This blown-up image of the Earth was taken through three color filters violet, blue and green and recombined to produce the color image. The background features in the image are artifacts resulting from the magnification ”1 So, that is how a technical apparatus 'sees' our world, humankind's fragile habitat. Before cult scientist Carl Sagan called it the "pale blue dot" in space, it was also known as "the blue marble" since the NASA-Apollo missions of the sixties and seventies. (Fig. 3)

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 26

Figure 1: Earth, described by scientist Carl Sagan as a "Pale Blue Dot," as seen by Voyager 1 from a distance of more than 4 billion miles (6.4 billion kilometers). Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Figure 2: "Earthrise", taken on December 24, 1968, by NASA/ Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders. Image source: https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/alsj/a410/AS8-14-2383HR.jpg.

https://www.nasa.gov/multimedia/imagegallery/image_feature_329.html.

Moreover, in the age of digitalization, picture-taking is everywhere getting more and more automatized, and more and more images are produced as well as generated and processed with the help of smart cameras with intelligent, deeplearning algorithms nowadays. These are the post-human eyes on Earth. Furthermore, Earth observation today is carried out via satellites in real-time. Environmental problems, wildfires, pollution of the seas, or melting of ice, for instance, can now be observed and tracked more easily and quickly.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 27

Figure 3: "The Blue Marble", by the NASA/ Apollo 17 crew (1972); taken by either Harisson Schmitt or Ron Evans. Image source:

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 28

Figure 4: In the Ptolemaic world view, the moon, the planets and the sun orbit the earth.

From Andreas Cellarius Harmonia Macrocosmica, 1660/61, Image source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d4/Cellarius_ptolemaic_system_c2.jpg.

Thousands of years, humankind was considering itself to be the center of the universe and looked up into the sky, to the distant stars that represented gods in their mythologies. Nevertheless, a bird ’ s view, for example, entered the history of painting before the Wright brothers even invented the first successful airplane at the beginning of the 20th century. Then planes, rockets, and satellites conquered the skies and, literally, broadened our horizons. Humankind suddenly could also look down at the Earth, and that changed how it sees itself fundamentally. Today, Google Earth and similar apps allow everyone to take a virtual tour around the globe in orbital scales. Recently, virtual globes have even substituted real globes or maps. (Fig. 4) No doubt, the photographic view of our planet from outer space is an epochal event of historical importance. Photographic images taken by satellites, moon astronauts, or space probes like Voyager 1 and 2, which stand in a long tradition of so-called artist illustrations and science fiction mock -ups, have created a new awareness of what it means to inhabit a small globe as the natural environment. It also brought about a sweeping change in consciousness and promoted new notions of a planetary unit and the “earth system.” French philosopher Bruno Latour calls it in preparation for an upcoming thoughtexhibition at the ZKM Karlsruhe the endangered ‘Gaia.2’

Thus, sometimes it takes a distance to see huge problems very close to you. For long, in cultural history the globe also has functioned as an illustration as well as a metaphor of the globalization that started at the latest by 1492 with the discoveries of Columbus. But by now looking down from space to the soil, humankind can observe and study various local as well as glob al catastrophes and human-made crises on its planet: “By now everybody knows that there is an existential threat to our collective conditions of existence, but very few people have any idea of how to cope with this new CRITICAL situation. It is very strang e, but citizens of many developed countries are disoriented; it is as if they were asked to land on a new territory, an Earth that they have long ignored having reacted to their action. The hypothesis we want to propose is that the best way to map this new Earth is to see it as a network of CRITICAL ZONES, which constitute a thin skin a few kilometers thick that has been generated over eons of time by life forms. Those life forms had completely transformed the original geology of the Earth, before humanity transformed it yet again over the last centuries.”3

Cybernetic theories, new technologies, and a long-lasting romanticism about nature coincide in this photographic image of the Earth as a fragile tiny sphere in the vast space of our universe such as, for example, produced and distributed by German Astro Al ex from inside the Cupola of the ISS. (Fig. 5-6)

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 29

Source: https://www.nasa.gov/content/astronaut-alexander-gerst-checks-out-station-cupola and https://twitter.com/Astro_Alex/status/490150268701790208/photo/1.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 30

Figures 5-6: Earth in our Window: Earth 'fits' in the Cupola of the International Space Station; photographed by Alexander Gerst on 6 July 2014, Image ESA/NASA.

REMOTEWORDS

Moreover, the climate change debate and the current philosophical concept of the so-called Anthropocene age are fundamentally shaped by the notion of the one planet. Thus, “one Earth unites many worlds,” states the CEO of the ZKM Karlsruhe, 2017, for an art project by REMOTEWORDS (Uta Kopp and Achim Mohné)4 , which emphasizes connectedness as well as cultural diversity in global unity. It is titled FIVE ROOFS | FIVE CONTINENTS: ONE EARTH UNITES MANY WORLDS for the GLOBALE event in Karlsruhe. (Fig. 7-12) Herefore, the Colognebased artist duo REMOTEWORDS installed a stark message with five words on five continents authored by Peter Weibel on the occasion of the 100 day-lasting ZKM exhibition. Its five parts, RW.26, RW.27, RW.28, RW.29, and RW.30, have been installed in Taipei at Taipei Artist Village, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, with Ghetto Biennale, in Kliptown, Johannesburg at SKY–Soweto Kliptown Youth, in Auckland at MIT, Manukau Institute of Technology, and in Karlsruhe in cooperation with ZKM in front of the museum ’ s building. The whole statement then could only be read from high above and by taking a virtual tour around the globe.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 31

Figures 7-12: REMOTEWORDS (Uta Kopp and Achim Mohné): "Five Roofs | Five Continents: ONE EARTH UNITES MANY WORLDS," 2017. Courtesy the artists. © Achim Mohné / VG Bild-Kunst.

Peter Weibel emphasized its central role for the GLOBALE event in Karlsruhe: The artist group REMOTEWORDS "... traveled five continents from New Zealand to North America and searched for places where they could place a word so significant that it could easily be captured by a satellite orbiting the Earth. In so far as this work collects information, it is an excellent example of the link between globalization and the so-called infosphere. By the way, the artists asked me for a five-word sentence for the five continents, and I gave them the following along the way: "One earth unites many worlds." By the way, the word "unites" is written on the forecourt of the ZKM. This is precisely what marks the theme: for from the small planet on which we live, we set out on a panicky search for exo-planets in the hope of finding suitable living conditions outside the Earth's sphere. But so far, we have only one earth on which we have the conditions necessary for life. Therefore, we must not destroy it. This "unites" is a word as important as "many," which stands for the existence of different cultures, languages, and peoples, i.e., for diversity. In physics, too, there is a constant search for the unification of contradictory theories such as the theory of relativity with the theory of quantum mechanics. Unifying or uniting is a primary theoretical task. You can see what unification means when you have no argument. The European Union cannot function without it. On the contrary, it makes Europe fall apart."5

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 32

Figure word UNITES by REMOTEWORDS Pamela C. Scorzin.

Thus, this epic public art project comprehends the physical globe in the tradition of the Land Art movement itself as an expanded art territory. Once updated on contemporary virtual globes like Google Earth, Bing or Apple Maps, the whole phrase ONE EARTH UNITES MANY WORLDS could be read comprehensively only by taking a virtual tour around the world that digitally references the impressive new scales and the orbital perspectives of our technologically net-worked times. As once Jenny Holzer in the realm of public art, REMOTEWORDS bring messages into environmental space, but by now, both physical -real as well as virtual-digital. The hand-painted, analog single words on the roofs and the ground instead were hard to be perceived by a local audience close to it. (Fig. 13).

Herewith, in the long-established modern art practices of parasitage as well as détournement , the artists secretly hacked a global surveillance system that is primarily used for several commercial, economic, and especially military services, but so far not for the arts. Referring to the heritage of prehistoric Earthworks like the mysterious Nasca lines and up to modernist Land Art USA6 , REMOTEWORDS is a long-term artistic and inter-disciplinary urban project in global measures founded in 2007 by Achim Mohné and Uta Kopp in Cologne, Germany. Established at the cross-over of art, literature, design, internet culture, and navigation technology, REMOTEWORDS now worldwide installs short messages and statements on roofs of cooperating partners such as cultural institutions and art centers. They are applied with paint in the form of permanent, capital letters in a kind of pixelated typography. Each collaboratively developed message represents a semantic unit with its particular hosting location and the environment. Thus, the site-specific analog words themselves are not directly visible on the spot but are necessarily subjected to the view from outer space via commercial satellite photography, hot air balloons, planes, or drones. Instead, they are experienced worldwide via virtual globes such as Google Earth, Apple, or Bing Maps. REMOTEWORDS literally takes the art audience to higher grounds.

In an interview with Stefanie Strigl artist Achim Mohné remarked: “We understood the virtual globes which appeared for the first time in 2005 as »Google Earth« as a new medium that would be interesting to cast artistically. We saw a »possibility space« in the truest sense. The entire surface of the earth was there like a white canvas, an unexploited action area which had only just come into being through the new technology. Based on this, in 2007 we developed the concept for »REMOTEWORDS« as a subversive strategy of »analogue hacking« In contrast to

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 33

graphic artists, we operate in harmony with institutions, but not with the distributors who transport our message. Satellites observe us without being asked and we send our message back on the same channel. (…) I think the attraction lies especially in the paradox of proximity and distance, i.e. that the visible messages are not occluded locally and can only be experienced by means of a medium, but the medium is globally com prehensible. In the tradition of »land art« we utilize the surface of the earth and process it nearly traditionally, not different from the draftsmen of the Nazca Lines thousands of years ago. However, we do not arrange these areas for a (potential) divine view, i.e. not in a natural sense, but with the goal of creating a new artefact that functions as an »orientation tool« in an extremely mobile era. ”7

In 2010, for the E-Culture Fair at Dortmund, the concept of this new public artproject by REMOTEWORDS had already been expanded into another digital realm, into a virtual game. 8 A large-scale, accessible satellite picture of the surrounds of the then exhibition space, the Dortmund U, invited each visitor to cover one roof with a comment. On the spot, the participants’ statements were directly applied to the satellite picture. Using REMOTEWORDS’ blog, virtual visitors from around the world could also contribute messages and comments on issues such as urbanity, navigation, digitality, virtual simulation, and the city (urban space), etc.

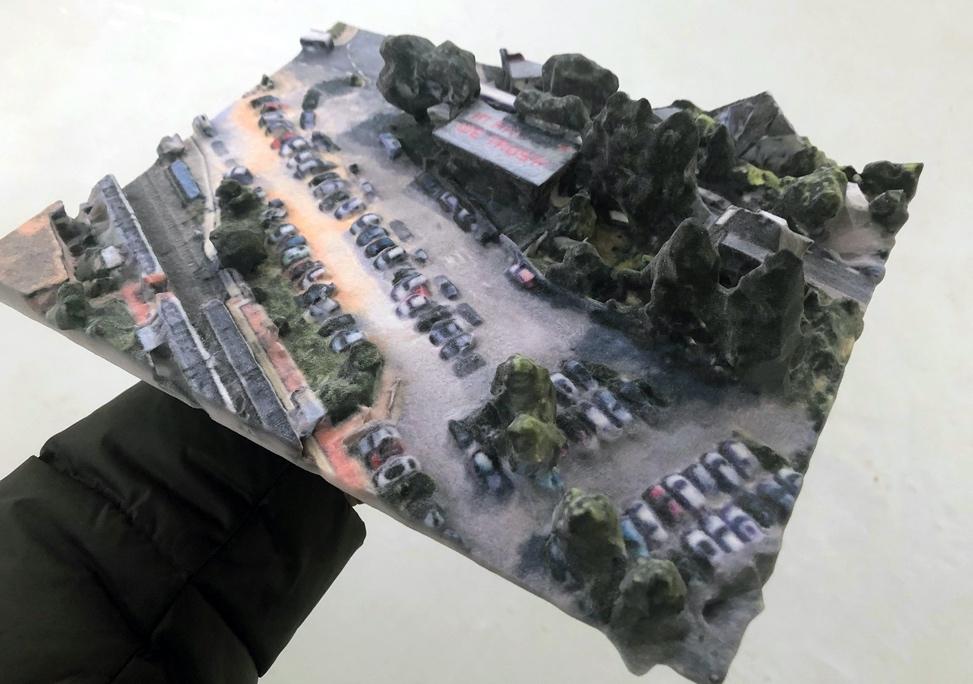

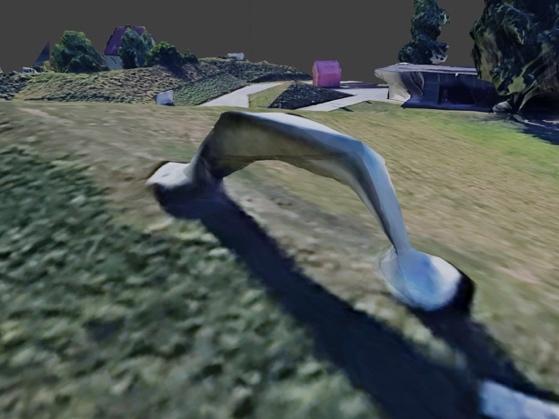

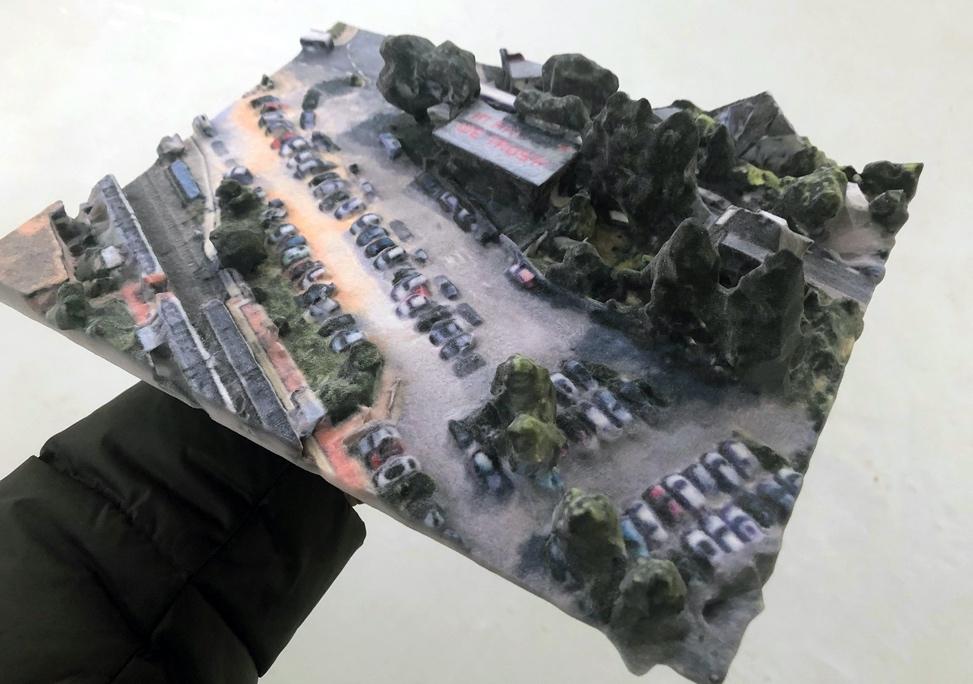

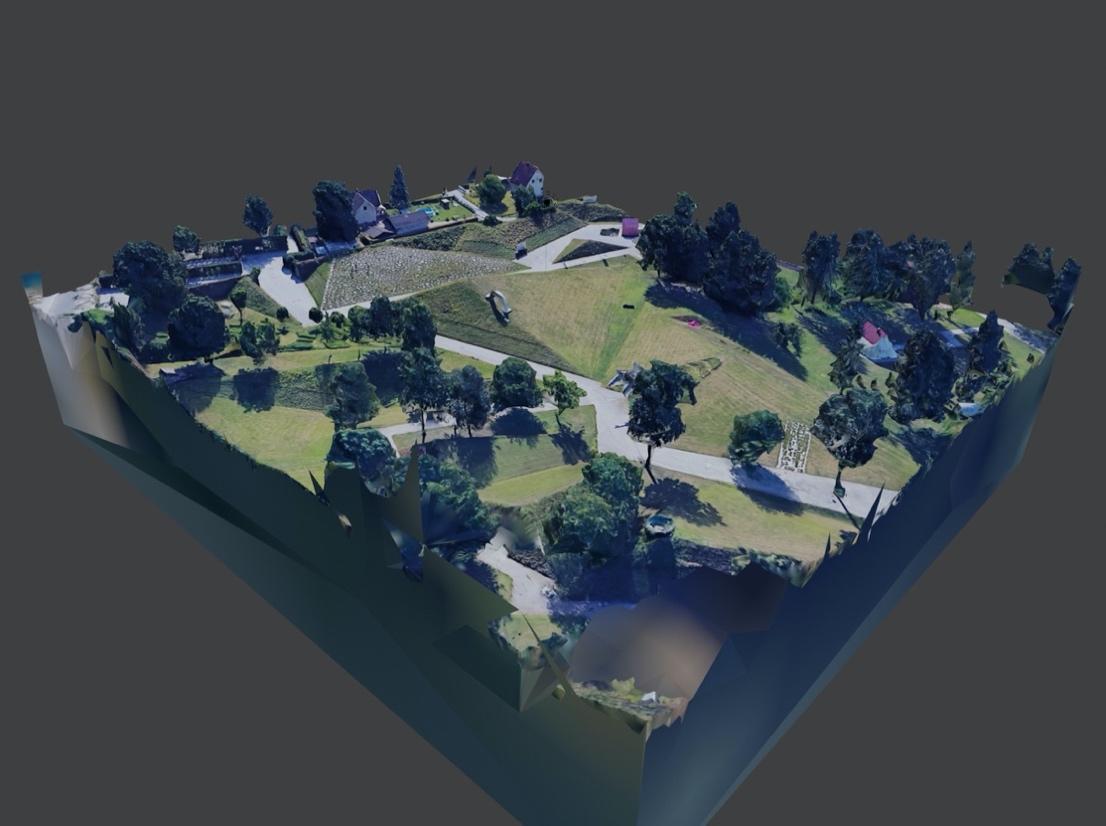

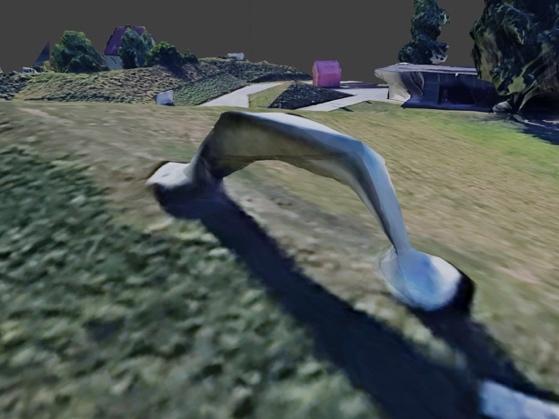

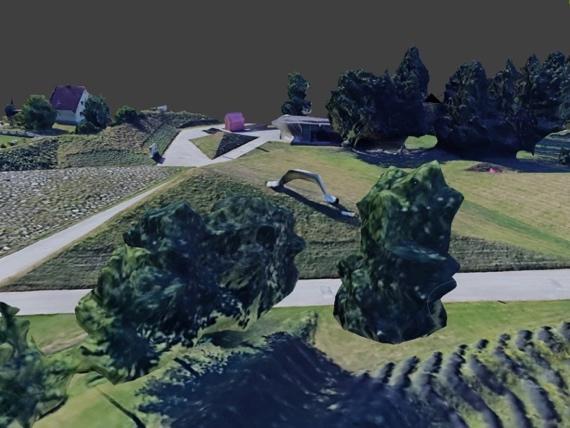

Another interactive game version was then launched in 2015, precisely 165 days before the start of the GLOBALE at the ZKM Karlsruhe, curated by Peter Weibel; moreover, the concept of this pioneering art project was being expanded back into real life again: A large-scale, individually accessible satellite picture of the exhibition premises of the ZKM Karlsruhe invited each visitor again to cover a roof with a short message. The individual statements were then instantly applied to the provided satellite picture by hand. Visitors as users were here asked to contribute comments once more on issues such as urbanity or globalization. But then, at predetermined times, remote-controlled drones would fly over the 10 x 6 m walkaround satellite picture. The pilotless aircraft was equipped with a CCTV system that, during its overflight, was relaying live images of the scenic area below onto a projection wall in the exhibition space. At the same, there, the digital live image was remarkably indistinguishable from a real flyover-video of Karlsruhe. (Fig. 14)

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 34

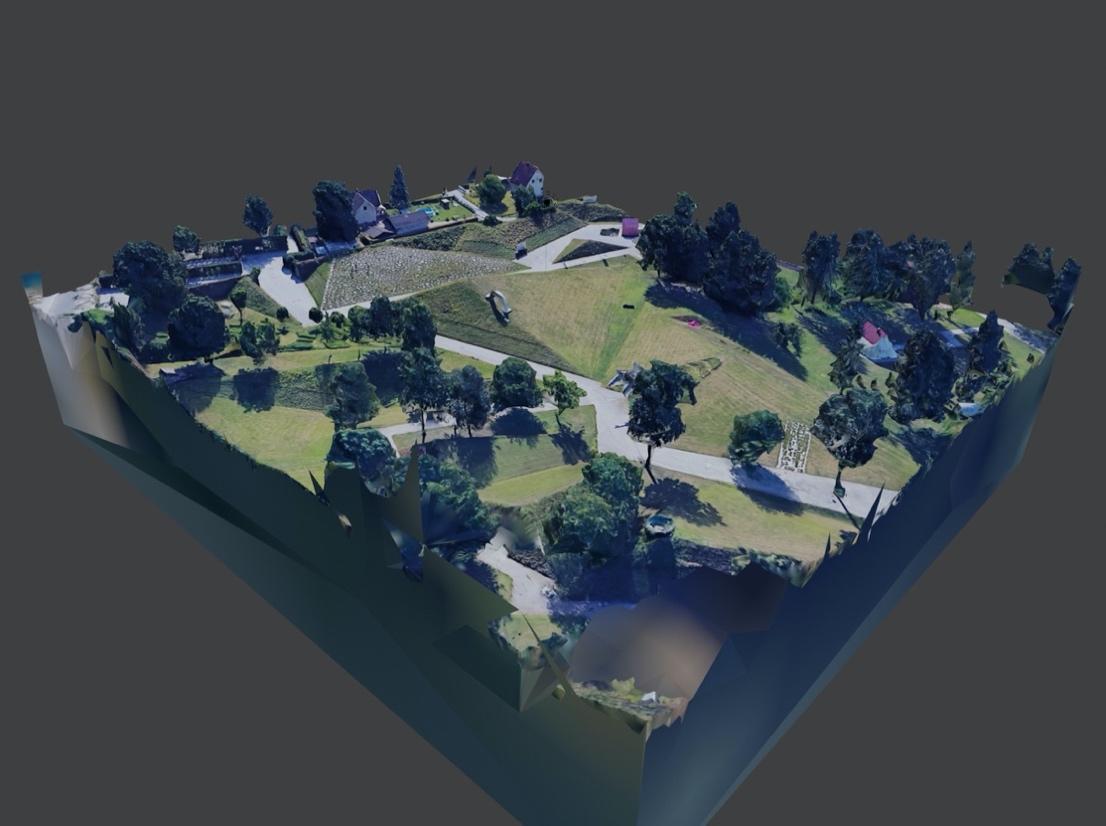

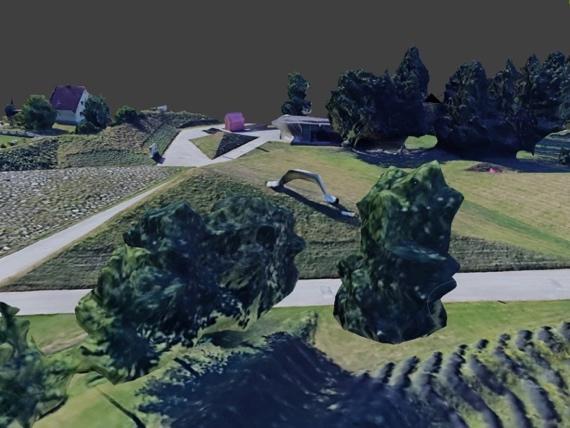

From Environmental Art to Climate Change Art

In November 2017, artist Achim Mohné installed another large-scale floor piece that needs to be viewed from an orbital perspective to be fully perceived. It ran parallel to the United Nations Climate Change Conference, which took place in Bonn, Germany. (Fig. 15-16) Here, Mohné transposed the famous "Earthrise"image from the digital realm of the internet onto the physical area of the Bundeskunsthalle museum forecourt, by aligning the digital pixels of the iconic NASA image with a corresponding number of concrete floor tiles. As a result of this, the German media artist recreated a low-tech copy as an analog, large-scale mosaic composed of 6400 square floor tiles, each 25 x 25 cm, total expanse 20 x 20 m; with floor paint in different colors: 14 shades of blue, 20 shades of grey as well as white and black. When seen at ground level, the image is unrecognizable and seemingly abstract. Still, the groundwork "0,0064 MEGAPIXEL Planet Earth Is Blue, And There Is Nothing I Can ’t Do" becomes strikingly visible as a pixelated image of the earth in aerial photographs and satellite images. The 6400 pixels, each 25 x 25 cm in size and adding up to an area of 20 x 20 meters, smartly corresponded to a digital camera resolution of just 0.0064 megapixels. Although the public art piece appears not to be aligned with its near surroundings, it is situated on a north-south axis so that it is perpendicular to the grid of virtual maps

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 35

Figure 14: REMOTEWORDS, interactive game version, ZKM Karlsruhe, 2015. © Achim Mohné / VG Bild-Kunst.

and appears straight ‘upright’ on virtual internet globes. Therefore, the low-tech analog format cannot be detected by digital spam filters and thus adopted into the data pools of virtual worlds such as Google Earth, Bing, or Apple Maps, which will automatically spread the information and data, or rather the smuggled-in artwork worldwide. With the next upgrade of the mentioned apps, the ‘new’ image will then become visible as ‘earth in space ’ seen from space thus, it is hidden in plain sight within these all-encompassing new, global surveillance technologies. Achim Mohné comments: “Earthrise is an analog color photograph taken by astronaut Bill Anders on 24 December 1968 during a lunar orbit of the American Apollo 8 mission. Hailed as 'the most influential environmental photograph ever taken,' it was published in the news magazine Time in January 1969. This pioneering photograph taken from space–and others like it–were the first to bring home the thinness of earth's atmosphere and to highlight the fragility and vulnerability of our planet. Just a few weeks later, David Bowie wrote his famous song Space Oddity : Bowie drew on the image, which has since acquired iconic status and become firmly rooted in our collective memory. ”9

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 36

Figure 15: "0,0064 MEGAPIXEL Planet Earth Is Blue, And There Is Nothing I Can’t Do" , Bonn: Bundeskunsthalle, Germany. Photo by Klaus Goehring. © Achim Mohné / VG Bild-Kunst.

Like Popstar David Bowie, Mohné has investigated questions of proximity and distance, inside and outside, up and down, strange and familiar. The artist's use of material exchanges and translations, reversals, filters, appropriations and adaptations, and last but not least, irritations prompts the viewers to halt and take a closer look. Furthermore, in times of 'fake news,' the question of the truthfulness and power of images or even words is crucial and acts as an appeal to the viewer's critical faculties. After all, everything depends on a flexible perspective: Every change of one's position, one's point of view, transforms the (analog) abstraction into a (digital) concreteness, into a pixelated digital image and vice versa. It would help if you found your standpoint anyhow. The more we engage with something that we initially do not understand, and the more we look at it from different angles and varying perspectives, the more we will eventually get out of our dawning deeper understanding. Moreover, it is for this reason that this new public art project is for Achim Mohné a symbolic as well as an activist artwork an appeal to be sensitive, attentive, and mindful in the way we treat each other and our shared space, so far humankind ’ s only habitable planet. For that, it seems, we need further to adopt at least an orbital perspective instead of a mere global.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 37

Figures 16: "0,0064 MEGAPIXEL Planet Earth Is Blue, And There Is Nothing I Can ’t Do," Bonn: Bundeskunsthalle, Germany. © Achim Mohné / VG Bild-Kunst.

Thus, compared to the "Earthrise"-image taken by an US-American astronaut, the tiny blue dot against a black background is an even more striking image since it allows humankind to look through a technical prosthesis and from a smart camera perspective. It solely comes from a mechanical space probe that is taking one last look at its place of origin before it leaves our solar system forever and disappears into interstellar space boldly going to where no man has gone before…Almost as a galactic postcard as well as a final farewell, it sent humankind a breathtaking image that far surpasses the icon of the rising Earth's globe taken from the moon in the late 1960s. Computer-supported technical apparatuses have long since taken over the production of images and deliver remarkable imagery that affects us, biological beings, most. In the so-called Space Age, orbital perspectives, in particular, have gained in importance and spread globally on the Internet. This kind of visuals range from computer-generated images for the big blockbuster cinema à la GRAVITY (2013, directed by Alfonso Cuarón) (Fig. 17), INTERSTELLAR (2014, directed by Christopher Nolan), THE MARTIAN (2015, directed by Ridley Scott) or VALERIAN AND THE CITY OF A THOUSAND PLANETS (2017, directed by Luc Besson) as well as popular culture to current science images that are distributed by NASA or ESA on the Internet and that ubiquitously pop up on our screens. These already common and familiar visuals now occupy our understanding of space as a matter of course, even before we all become space tourists ourselves. However, we can already immerse ourselves in orbital balloon rides in AR/VR installations like in Marie Lienhard ’ s over-whelming artwork: “A two-meter diameter gilded helium balloon, onto which a 360° panoramic camera is attached, rises into the skies. This camera films the entire environment: the world gets smaller and smaller on its way to the edge of space until it bursts at 35 km altitude.

Image source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1454468/mediaviewer/rm2605702656.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 38

Figure 17: Screengrab from GRAVITY (2013, directed by Alfonso Cuarón).

The spectacular moment in which the balloon explodes, spreads its gold particles, as well as its fall back to earth, are also part of the 360° VR video. The fully immersive virtual reality results visually give a surprisingly overwhelming physical experience of weightlessness.”10 (Fig. 18)

We use such specific digital imageries today as a matter, of course, to travel to orbital dimensions, at least in our minds, when we access apps installed on our smartphones and use Oculus Rift The transgression of boundaries, the broadening of horizons, and the consciousness of no-limits in the sign of the ‘one earth’ seen from a divine view has come to a further discourse in contemporary art practices. They all stand in the tradition of the "Whole Earth Catalog," which in the late 1960s was a central document of the California counterculture and became highly influential to the Silicon Valley Techs, Nerds, and Sci Fi Geeks Besides already anticipating the concept of the Internet, it also played a crucial role in mediating and popularizing images and concepts of the critical ‘earth system.’ At the same time, megalomanic Earth Works and Land Art flourished across the USA with major ground projects by Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, and James Turrell, among others. So, both the vision of a global Internet and central concepts of the ecology movement can be traced back to this moment, too, that combined science fiction with environmental awareness, and transferred new economicsystemic ideas to society, politics, and the arts.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 39

Figure 18: Videostill ‘Explosion’ from LOGICS OF GOLD by Marie Lienhard, 2018; Virtual reality video, 5’00”, 22 carat gold flakes, sheet metal gold, weather balloon & helium, 360° panorama camera. Image source: http://marie-lienhard.com/logics-of -gold.

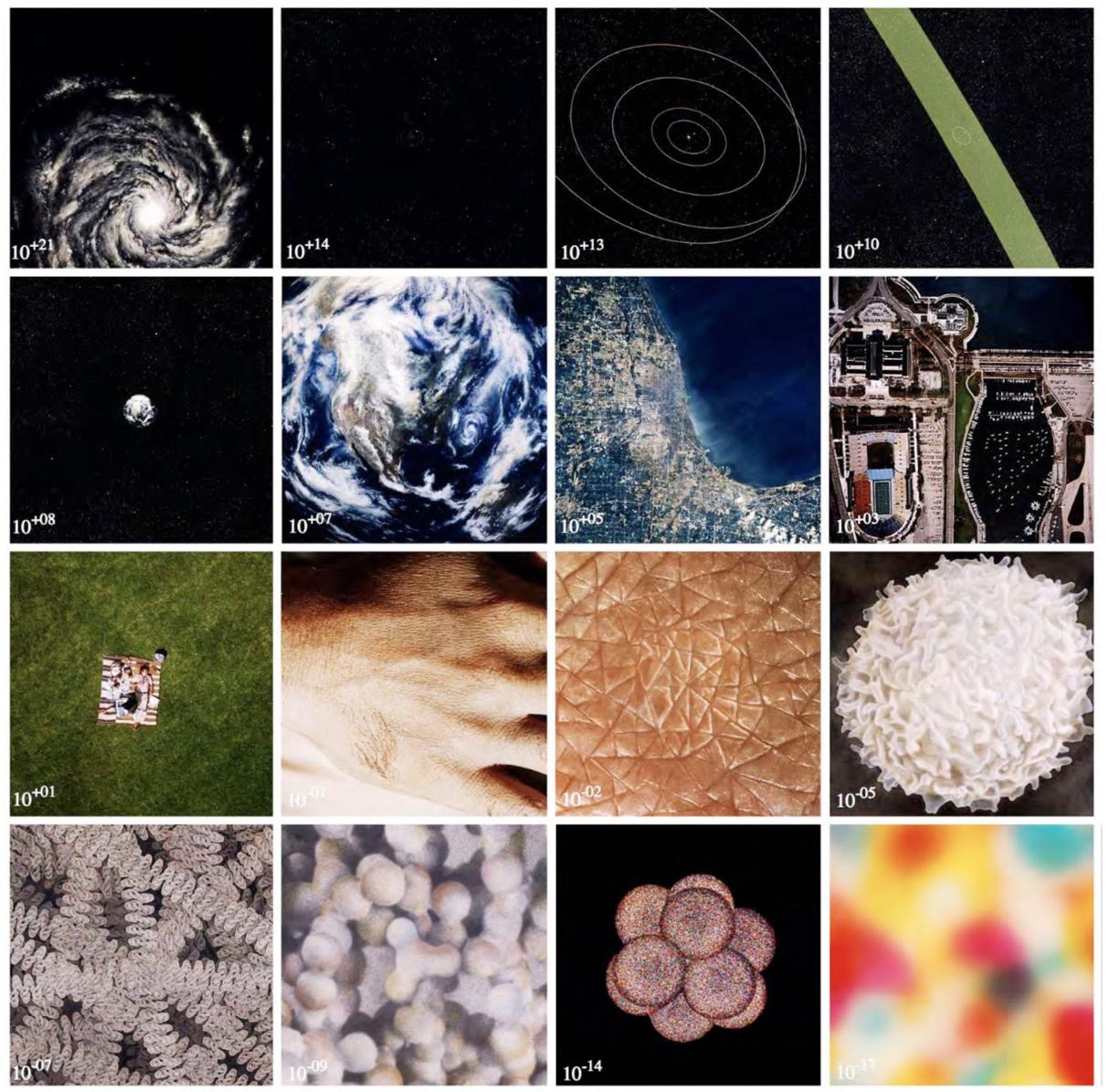

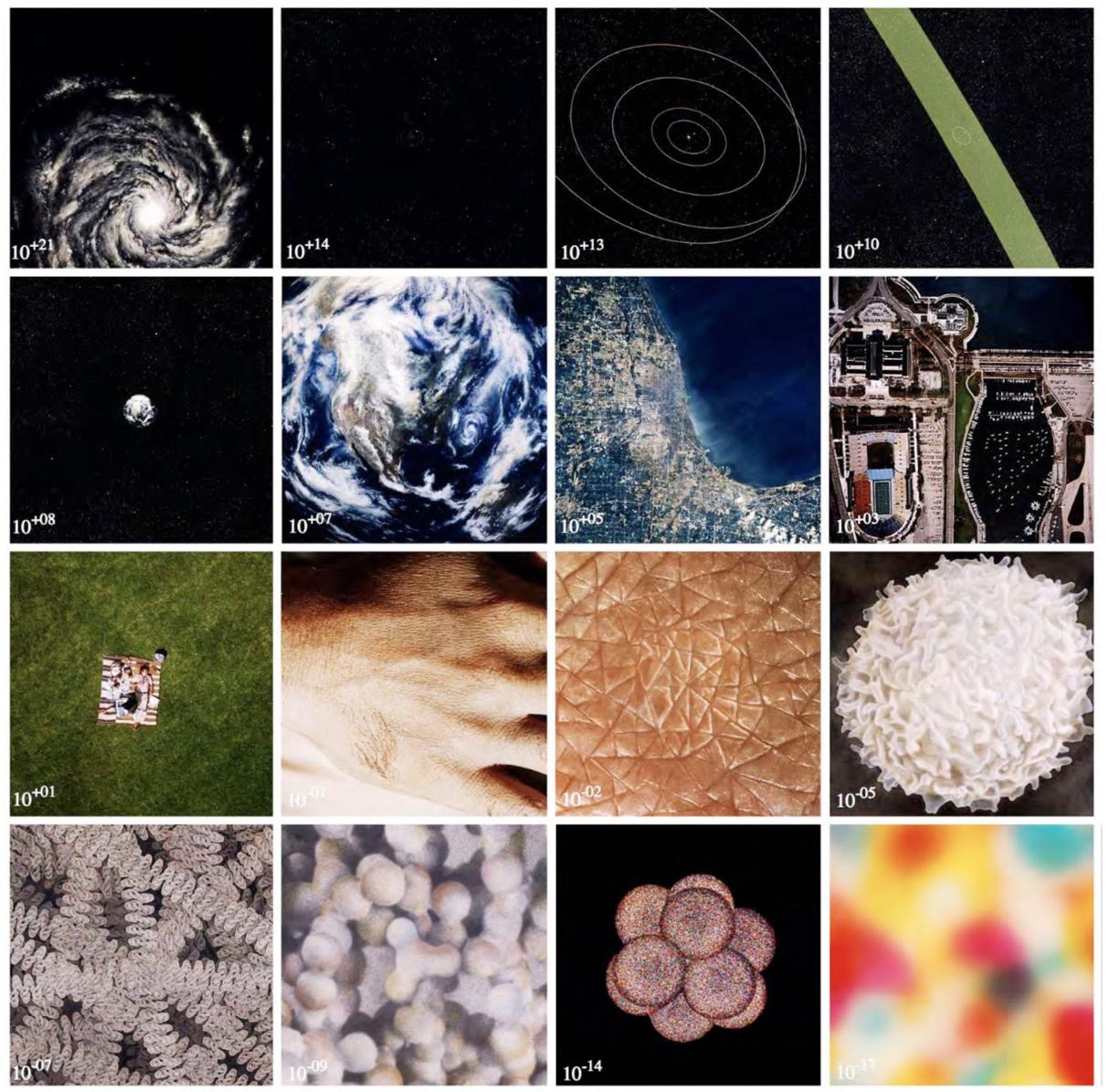

The Orbital View and the Arts in the Age of the Anthropocene

The Anthropocene is a recently proposed geological epoch dating from the commencement of significant human impact on Earth's geology and ecosystems, including, but not limited to, anthropogenic climate change. Contemporary art reacts to this epochal shift and to the accompanying change from local via global to orbital perspectives in a variety of ways. Yet, it is not only about new spectacular views, but in many ways about fundamental changes of perception and experience that lead to a new awareness and heightened environmental consciousness as in Eames' epochal short film "The Power of Ten" (1968). (Fig. 19)

Image source: https://medium.com/@barryvacker/powers-of-ten -honoring-the-40th-anniversary-of

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 40

Figure 19: Filmstills from "Power of Ten" by Ray and Charles Eames, 1968.

the-existential-masterpiece-5c5affa46249.

Charles and Ray's documentary one of the most famous short films ever made has been interpreted as an exemplar for teaching and understanding the importance of measure and scale. It also exemplifies the arising shift from terrestrial to orbital perspectives in its time: “Starting at a lakeside picnic in Chicago, 'Powers of Ten' transports us to the outer edges of the universe. Every ten seconds we view the starting point from ten times farther out until our own galaxy is visible as nothing more than a speck of light among many others. Returning to Earth with breathtaking speed, we move inward into the hand of the sleeping pic nicker with ten times more magnification every ten seconds. The journey ends inside a proton of a carbon atom, which is within a DNA molecule inside of a white blood cell.”11

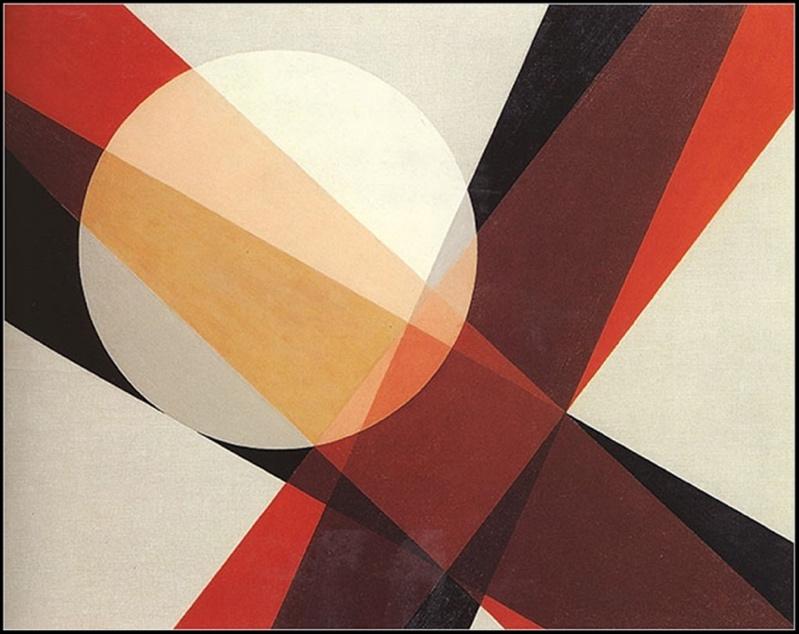

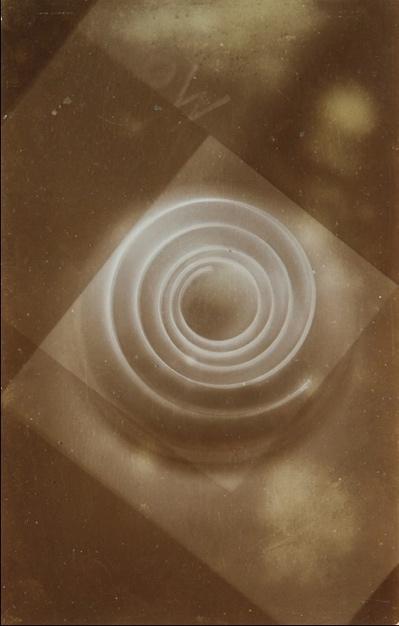

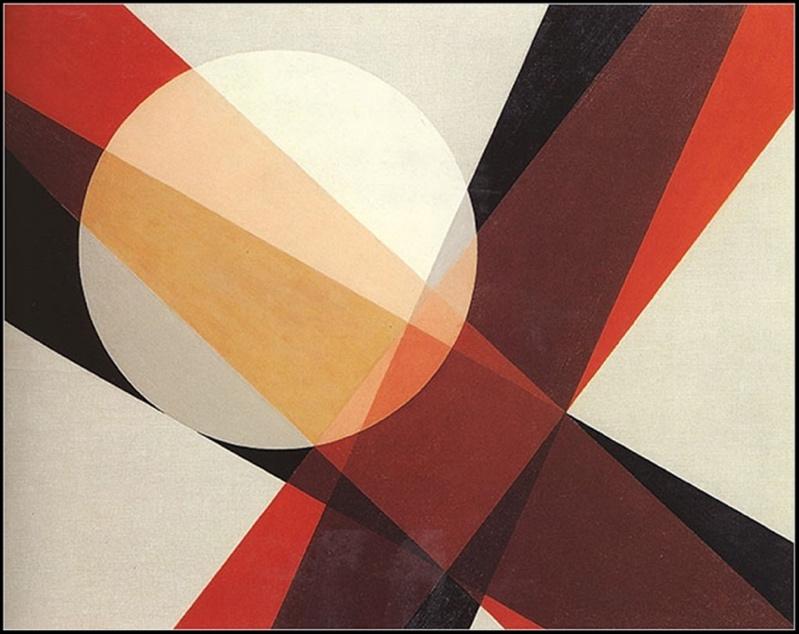

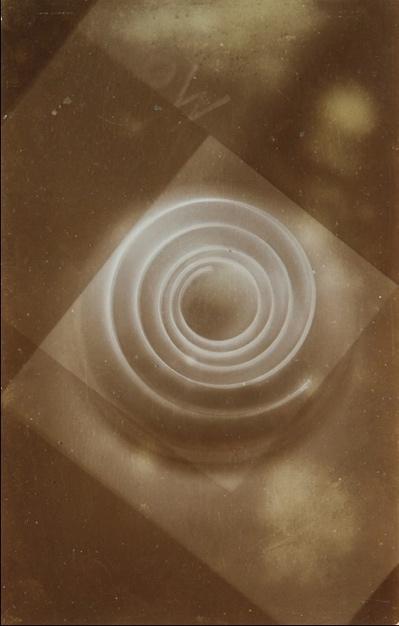

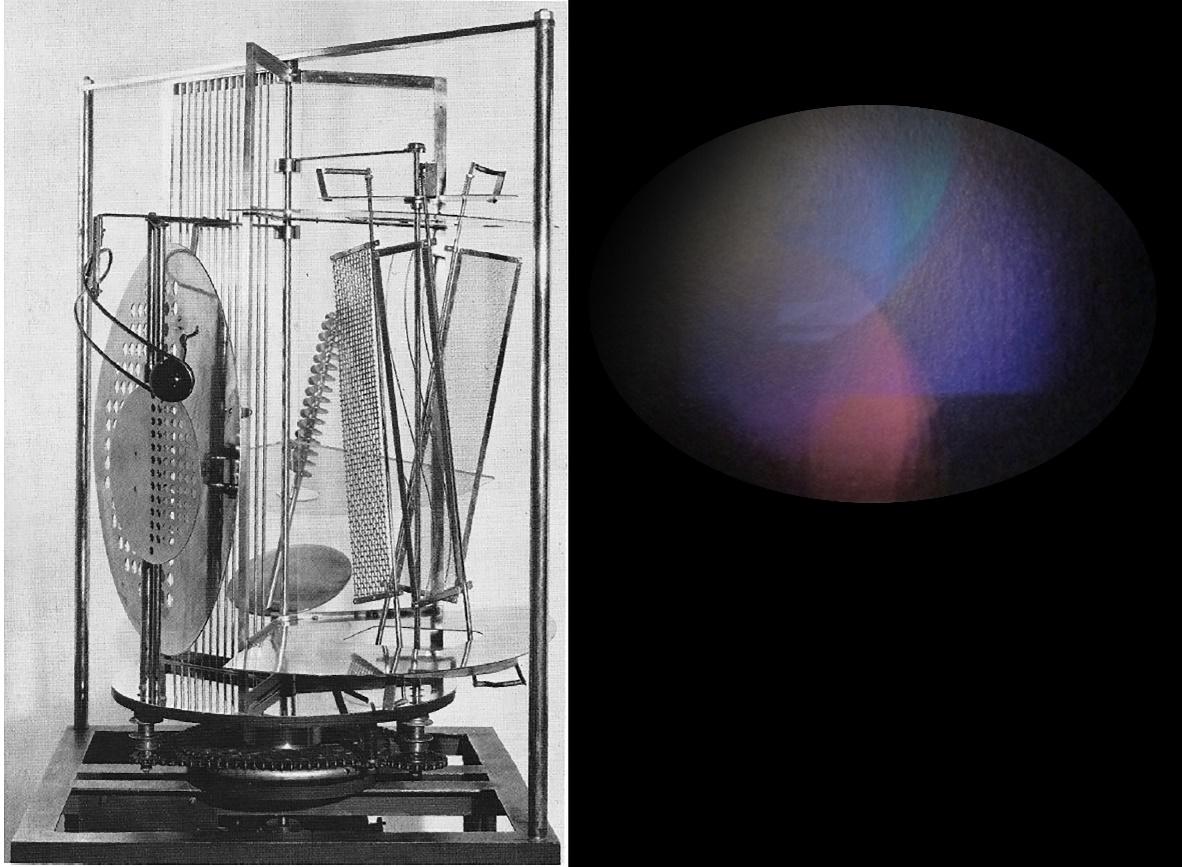

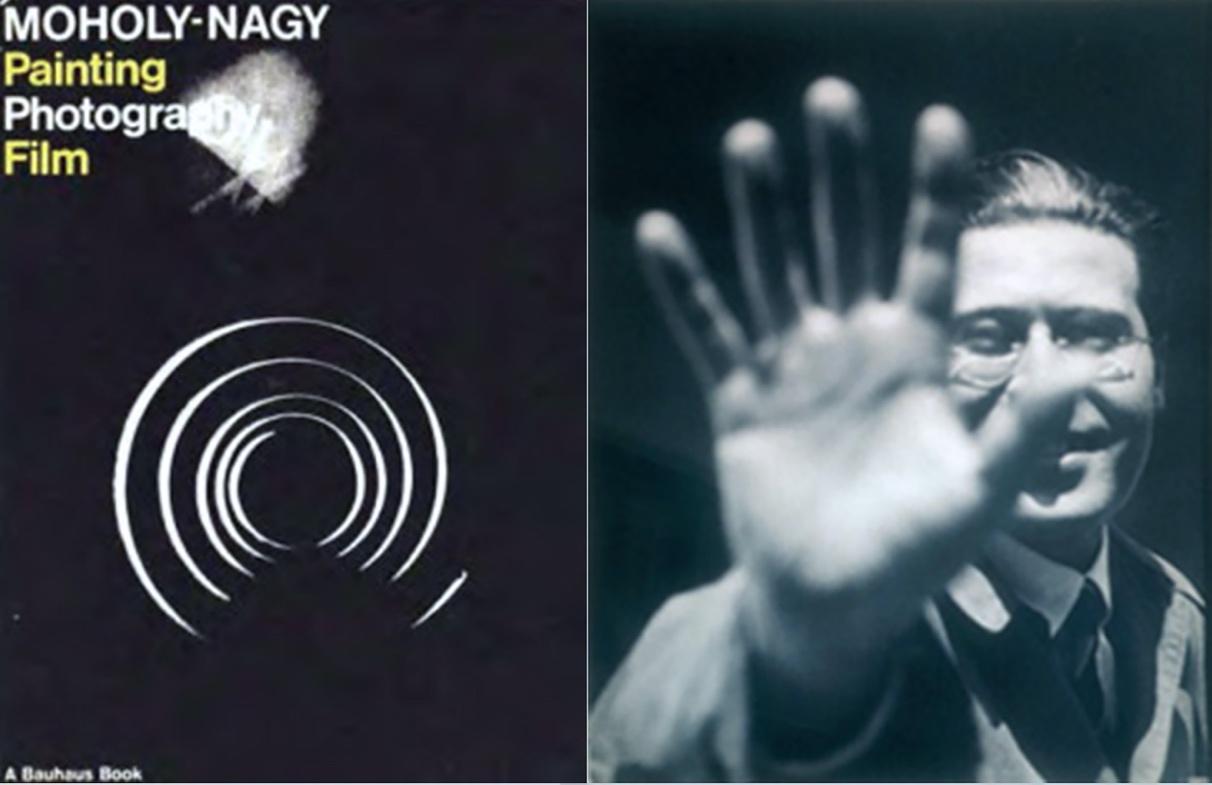

The artist couple Charles and Ray Eames first created this documentary short in the Sixties The film was called ‘A Rough Sketch for a Proposed Film Dealing with the Powers of Ten and the Relative Size of Things in the Universe.’ In the spirit of iteration for which the artists are known, they rereleased it in 1977 under the name ‘Powers of Ten.’ Their film is an adaptation of the 1957 book, ‘Cosmic View,’ by Kees Boeke, and more recently is the basis of a new book version. Both the film and book adaptations follow the form of Boeke’ s seminal work; however, they feature color and photography rather than black and white drawings. In 1998, “Powers of Ten” was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”12