20 h C &C A E i S l N Y k N b 8 N Y0107 18 NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_COVER_BL.indd 4

22/10/18 18:58

4. Joan Mirรณ

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_IFC+IBC_BL.indd 2

22/10/18 18:58

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_IFC+IBC_BL.indd 1

20/10/18 17:49

12. Jean-Michel Basquiat

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 2

22/10/18 09:12

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 3

22/10/18 09:12

6. Alberto Burri

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 4

22/10/18 09:13

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 5

22/10/18 09:13

3. George Condo

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 6

22/10/18 09:13

20th Century & Contemporary Art Evening Sale New York, 15 November 2018, 5pm

20th Century & Contemporary Art Department Contact

Auction & Viewing Location 450 Park Avenue New York 10022

Head of Sale Amanda Lo Iacono +1 212 940 1278 aloiacono@phillips.com Researcher/Writer Patrizia Koenig +1 212 940 1279 pkoenig@phillips.com Cataloguer Annie Dolan +1 212 940 1288 adolan@phillips.com

Auction

Sale Designation When sending in written bids or making enquiries please refer to this sale as NY010718 or 20th Century & Contemporary Art Evening Sale.

Thursday, 15 November 2018, 5pm

Viewing

Absentee and Telephone Bids

2 – 15 November Monday – Saturday 10am – 6pm Sunday 12pm – 6pm

tel +1 212 940 1228 fax +1 212 924 1749 bidsnewyork@phillips.com

Administrator Brittany Jones +1 212 940 1255 bjones@phillips.com Copyright & Special Catalogues Coordinator Roselyn Mathews +1 212 940 1319 rmathews@phillips.com

Special thanks Richard Berardino, Jean Bourbon, Orlann Capazorio, Francesca Carnovelli, Courtney Chapel, Cloe Cobbs, Anaar Desai, Ryan Falkowitz, Daren Khan, Sophia Kinell, Christine Knorr, Andrea Koronkiewicz, Matthew Kroening, Lianne Melkes, Tirso Montan, Steve Orridge, Kent Pell, Alessandro Penazzi, Danielle Polovets, Simone Pomposi, Alex Powell, James Reeder, Brendon Swanson, Jef Velazquez

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 7

22/10/18 09:14

Our Team. Executives.

20th Century & Contemporary Art.

Ed Dolman

Cheyenne Westphal

Jean-Paul Engelen

Robert Manley

Chief Executive Ofcer

Chairman

+1 212 940 1241 edolman@phillips.com

+44 20 7318 4044 cwestphal@phillips.com

Worldwide Co-Head of 20th Century & Contemporary Art, Deputy Chairman

Worldwide Co-Head of 20th Century & Contemporary Art, Deputy Chairman

+1 212 940 1390 jpengelen@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1358 rmanley@phillips.com

Š Brigitte Lacombe

Senior Advisors. Hugues Jofre

Arnold Lehman

Ken Yeh

Senior Advisor to the CEO

Senior Advisor to the CEO

Senior International Specialist

+44 207 901 7923 hjofre@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1385 alehman@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1257 kyeh@phillips.com

Deputy Chairmen. Svetlana Marich

Jonathan Crockett

Peter Sumner

Miety Heiden

Alexander Payne

Vanessa Hallett

Vivian Pfeifer

Marianne Hoet

Worldwide Deputy Chairman

Deputy Chairman, Asia, Head of 20th Century & Contemporary Art, Asia

Deputy Chairman, Europe, Senior International Specialist, 20th Century & Contemporary Art

Deputy Chairman, Head of Private Sales

Deputy Chairman, Europe, Worldwide Head of Design

Deputy Chairman, Americas, Worldwide Head of Photographs

Deputy Chairman, Americas, Head of Business Development, Americas

+44 20 7318 4052 apayne@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1243 vhallett@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1392 vpfeifer@phillips.com

Deputy Chairman, Europe, Senior Specialist, 20th Century & Contemporary Art

+44 20 7318 4010 smarich@phillips.com

+852 2318 2023 jcrockett@phillips.com

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 8

+44 20 7318 4063 psumner@phillips.com

+44 20 7901 7943 mheiden@phillips.com

+32 3257 3026 mhoet@phillips.com

22/10/18 09:15

30. Jonas Wood

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 9

22/10/18 09:15

2. KAWS

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 10

22/10/18 09:15

Phillips Division of

20th Century & Contemporary Art New York.

Scott Nussbaum

Rachel Adler Rosan

Kevie Yang

Amanda Lo Iacono

John McCord

Rebekah Bowling

Sam Mansour

Katherine Lukacher

Head of Department

Senior Specialist

Senior Specialist

Head of Evening Sale

Head of Online Sales

+1 212 940 1333 radlerrosan@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1254 kyang@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1278 aloiacono@phillips.com

Head of Day Sale, Afernoon

Head of New Now Sale

+1 212 940 1354 snussbaum@phillips.com

Head of Day Sale, Morning +1 212 940 1261 jmccord@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1250 rbowling@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1219 smansour@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1215 klukacher@phillips.com

Jeannette van Campenhout

Annie Dolan

Olivia Kasmin

Carolyn Mayer

Maiya Aiba

Avery Semjen

Patrizia Koenig

Cataloguer

Cataloguer

Cataloguer

Cataloguer

Cataloguer

Researcher/Writer

+1 212 940 1288 adolan@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1312 okasmin@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1206 cmayer@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1387 maiba@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1207 asemjen@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1279 pkoenig@phillips.com

Specialist +1 212 940 1391 jvancampenhout@phillips.com

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 11

22/10/18 09:16

London. Dina Amin Head of Department +44 20 7318 4025 damin@phillips.com

Nathalie ZaquinBoulakia International Specialist +44 20 7901 7931 nzaquin-boulakia@ phillips.com

Jonathan Horwich

Matt Langton

Rosanna Widén

Henry Highley

Tamila Kerimova

Simon Tovey

Senior Specialist

Senior Specialist

Senior Specialist

Head of Evening Sale

Head of Day Sale

Head of New Now Sale

+44 20 7901 7935 jhorwich@phillips.com

+44 20 7318 4074 mlangton@phillips.com

+44 20 7318 4061 hhighley@phillips.com

+44 20 7318 4061 hhighley@phillips.com

+44 20 7318 4065 tkerimova@phillips.com

+44 20 7318 4084 stovey@phillips.com

Kate Bryan

Lisa Stevenson

Charlotte Gibbs

Louise Simpson

Clara Krzentowski

Specialist

Cataloguer

Cataloguer

Cataloguer

Researcher & Writer

+44 20 7318 4050 kbryan@phillips.com

+44 20 7318 4093 lstevenson@phillips.com

+44 20 7901 7993 cgibbs@phillips.com

+44 20 7901 7911 lsimpson@phillips.com

+44 20 7318 4064 ckrzentowski@phillips.com

Isaure de Viel Castel

Sandy Ma

Charlotte Raybaud

Danielle So

Delissa Handoko

Head of Department, Asia

Head of Evening Sale

Head of Day Sale

Cataloguer

Cataloguer

+852 2318 2025 isauredevielcastel @phillips.com

+852 2318 2025 sma@phillips.com

+852 2318 2026 craybaud@phillips.com

+852 2318 2027 dso@phillips.com

+852 2318 2000 dhandoko@phillips.com

Hong Kong.

International Specialists & Regional Directors. Americas. Cândida Sodré

Carol Ehlers

Lauren Peterson

Melyora de Koning

Blake Koh

Kaeli Deane

Valentina Garcia

Cecilia Lafan

Regional Director, Consultant, Brazil

Regional Director, Specialist, Photographs, Chicago

Regional Representative, Chicago

Regional Director, Los Angeles

Head of Latin American Art, Los Angeles

Specialist, Miami

Regional Director, Consultant, Mexico

+55 21 999 817 442 csodre@phillips.com

+1 773 230 9192 cehlers@phillips.com

+1 310 922 2841 lauren.peterson @phillips.com

Senior Specialist, 20th Century & Contemporary Art, Denver

+1 323 383 3266 bkoh@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1352 kdeane@phillips.com

Maura Smith

Silvia Coxe Waltner

Regional Director, Palm Beach

Regional Director, Seattle

+1 508 642 2579 maurasmith@phillips.com

+1 206 604 6695 scwaltner@phillips.com

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 12

+1 917 657 7193 mdekoning@phillips.com

+1 917 583 4983 vgarcia@phillips.com

+52 1 55 5413 9468 crayclafan@phillips.com

22/10/18 09:16

Europe. Laurence Calmels

Maria Cifuentes

Laurence Barret-Cavy

Regional Director, France

Specialist, 20th Century & Contemporary Art, France

Specialist, 20th Century & Contemporary Art, Paris

+33 686 408 515 lcalmels@phillips.com

+33 142 78 67 77 mcifuentes@phillips.com

+33 633 12 32 04 lbarretcavy@phillips.com

Kalista Fenina

Julia Heinen

Specialist, 20th Century & Contemporary Art, Moscow

Specialist, 20th Century & Contemporary Art, Regional Director, Zurich

+7 905 741 15 15 kfenina@phillips.com

+41 79 694 3111 jheinen@phillips.com

Dr. Nathalie Monbaron Regional Director, Geneva +41 22 317 81 83 nmonbaron@phillips.com

Dr. Alice Trier

Carolina Lanfranchi

Maura Marvao

Specialist, 20th Century & Contemporary Art, Germany

Regional Director, Senior International Specialist, 20th Century & Contemporary Art, Italy

International Specialist, Consultant, 20th Century & Contemporary Art, Portugal and Spain

+39 338 924 1720 clanfranchi@phillips.com

+351 917 564 427 mmarvao@phillips.com

+49 173 25 111 69 atrier@phillips.com

Asia. Kyoko Hattori

Jane Yoon

Sujeong Shin

Wenjia Zhang

Alicia Zhang

Cindy Yen

Meiling Lee

Iori Endo

Regional Director, Japan

International Specialist, 20th Century & Contemporary Art, Regional Director, Korea

Associate Regional Representative, Korea

Regional Director, Shanghai

Associate Regional Representative, Shanghai

International Specialist, Taiwan

Regional Representative, Japan

+82 10 7305 0797 sshin@phillips.com

+86 13911651725 wenjiazhang@phillips.com

+86 139 1828 6589 aliciazhang@phillips.com

Senior Specialist, Watches & Jewellery, Taiwan

+886 908 876 669 mlee@phillips.com

+44 20 7318 4039 iendo@phillips.com

+81 90 2245 6678 khattori@phillips.com

+82 10 7389 7714 jyy@phillips.com

+886 2 2758 5505 cyen@phillips.com

Business Development. Americas.

Europe.

Asia.

Vivian Pfeifer

Guy Vesey

Lilly Chan

Deputy Chairman, Americas, Head of Business Development, Americas

Head of Business Development & Marketing, Europe

Managing Director, Asia, Head of Business Development, Asia

+1 212 940 1392 vpfeifer@phillips.com

+44 20 7901 7934 gvesey@phillips.com

+852 2318 2022 lillychan@phillips.com

Client Advisory. New York.

Europe.

Philae Knight

Jennifer Jones

Liz Grimm

Yassaman Ali

Vera Antoshenkova

Client Advisory Director

Director of Trusts, Estates & Valuations

Business Development Associate

Client Advisory Director

Client Advisory Manager

+1 212 940 1272 jjones@phillips.com

+1 212 940 1342 egrimm@phillips.com

+44 20 7318 4056 yali@phillips.com

+44 20 7901 7992 vantoshenkova@ phillips.com

+1 212 940 1313 pknight@phillips.com

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 13

Giulia Campaner Mendes Associate Client Advisory Manager +44 20 7318 4058 gcampaner@phillips.com

Margherita Solaini Business Development Associate +39 02 83642 453 MSolaini@phillips.com

22/10/18 09:16

Lots 1–41 Thursday, 15 November 2018 5pm, sharp

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 14

22/10/18 09:17

13. Andy Warhol

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 15

22/10/18 09:17

1. Christina Quarles

b. 1985

Pull on Thru Tha Nite signed, titled and dated “Christina Quarles 2017 “PULL ON THRU THA NITE”” on the reverse. acrylic on canvas. 60 x 56 in. (152.4 x 142.2 cm.). Painted in 2017. Estimate $30,000-50,000

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 16

22/10/18 09:19

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 17

22/10/18 09:19

Provenance David Castillo Gallery, Miami Private Collection Exhibited Miami, David Castillo Gallery, Baby, I Want Yew To Know All Tha Folks I Am, December 4, 2017 – January 31, 2018 Literature Sarah Burke, “Two Artists on Creating Outside of the Art World’s White, Patriarchal Rules”, Broadly, February 21, 2018, online (illustrated) Wendy Vogel, “Christina Quarles”, Art in America, March 1, 2018, online (illustrated)

Bodies are in states of fux in Christina Quarles’ captivating paintings, twisting and turning across the canvas in a kaleidoscopic array of color. Epitomizing Quarles’ painterly upending of fxed notions of race, gender and space, Pull on Thru Tha Nite is a vivid example of the breakthrough body of work that catapulted the Los Angeles-based artist to widespread acclaim. Within the course of just 19 months following

Agnolo Bronzino, Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time, 1540–1550. National Gallery, London, Image Art Resource, NY

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 18

her frst ever solo gallery exhibition in 2017, Quarles’ work has been included in Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon at the New Museum, New York, Fictions at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and in the biennial Made in L.A. 2018 at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, where she was lauded “as perhaps the biennial’s most exciting discovery” (Christopher Knight, “Made in L.A. 2018”, Los Angeles Times, June 5, 2018, online). Quarles is widely celebrated as one of the most unique voices of her generation, a reputation solidifed by her frst museum solo exhibition currently on view at the Berkeley Art Museum. Engaging with and subverting the trope of the female nude in art history, Quarles constructs fgures whose bodies are as malleable as notions of gender, race, and sexuality. While working within a lineage of fgurative painters as diverse as Egon Schiele, Francis Bacon, Leon Golub, David Hockney and Marlene Dumas, Quarles deliberately channels her lived experiences as a “queer, cis woman who is black but is ofen mistaken as white” into pictorial worlds of painterly excess and ambiguity (Christina Quarles, quoted in Christina Quarles, Matrix 271, exh. brochure, University of California, Berkeley Art Museum, 2018, online). Many of Quarles’ paintings depict predominantly female fgures in embrace, and in the present work too, she has depicted three ambiguously intertwined bodies, with the seated woman at the lower lef supporting the weight of two elongated fgures bent at the waist. Quarles deliberately allows the bodies to progressively move towards the brink of dissolution, only vaguely rendering the right fgure with the trace of a paint brush, yet characteristically articulates the hands with remarkable fnesse, while the face lingers only as a ghostly trace. It is this formal distinction that conveys Quarles’ conception of these works as portraits of living within a body: whereas we only occasionally catch glimpses of our faces, hands are the most fully realized extensions of ourselves that we see interact with the world around us. It is telling that these fgures are not based on specifc subjects, but spring from the artist’s own experiences and inimitable memory of the human body, the result of many years attending life drawing classes, something the artist continues to do to this

22/10/18 09:20

Francis Bacon, Triptych (detail), 1967. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Artwork © 2018 Estate of Francis Bacon/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ DACS, London

which Quarles jumps from one painterly technique to the other: she variously thins paint into translucent washes, lays it down with thick impasto, or draws with it to precisely render the fgures’ hands and feet. Trompe l’oeil efects mingle with areas of raw canvas, while gestural marks border against crisply defned lines and edges.

day. Moving beyond conventional fesh tones, Quarles constructs otherworldly vignettes that teeter between fguration and abstraction. Figures are caught in states of painterly metamorphosis as they inhabit worlds defned by multiple positions and shifing perspectives, in many ways refective of Quarles’ subjective experience of displacement. Exemplary of the artist’s strategy of employing planar shapes as compositional devices to intersect the canvas, the present work features a dotted picture plane that foats across the white canvas. While the resulting negative space suggests a hilly landscape with a starry sky in the distance, it also draws attention to the way in which the fgures are confned by the edges of the canvas and the compositional elements used to frame them – alluding to the Foucauldian notion of the culturally determined body, whereby sexuality is viewed as an efect of specifc power relations within a given environment. Quarles sees “these fgures existing solely within the materiality and limitations of the painting itself” (Christina Quarles, quoted in Tyler Green, “Christina Quarles and Peter Hujar”, The Modern Arts Podcast, no. 352, August 2, 2018, online). Indeed, the fuidity with which these bodies traverse the picture plane is in many ways paralleled by the apparent ease with

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 19

While Quarles’ body of work extends the fgurative investigations of such painters as Sue Williams, Nicole Eisenman, and Cecily Brown, her painterly practice appears to more specifcally conjure the ghosts of such abstract painters as Helen Frankenthaler and Willem de Kooning. Engaging with the rich history of painting, Quarles adeptly constructs a hybrid universe where the human body is untethered from fxed notions of identity and representation. It is this fresh take on art history that prompted art critic Peter Schjeldahl to highlight Quarles’ contribution to the New Museum’s Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon exhibition. “The happiest surprise in Trigger is a trend in painting that takes inspiration from ideas of indeterminate sexuality for revived formal invention,” he wrote, adding that Quarles can efectively be seen to “return to an old well that suddenly yields fresh water. Styles fade into history when they use up their originating impulses. New motives may snap them back to vitality…” (Peter Schjeldahl, “The Art World as Safe Space”, The New Yorker, October 9, 2017, online). Multiplicity, ambiguity and fantasy reign in Pull on Thru Tha Nite — encouraging the viewer to question the subjectivity and ambiguities of their own existence.

Cecily Brown, Trouble in Paradise, 1999. Tate Gallery, London, Artwork © Cecily Brown

22/10/18 09:20

○◆

2. KAWS

b. 1974

UNTITLED (FATAL GROUP) signed and dated “KAWS..04” on the reverse. acrylic on canvas. 68 1/8 x 68 1/8 in. (173 x 173 cm.). Painted in 2004. Estimate $700,000-900,000

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 20

22/10/18 09:21

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 21

22/10/18 09:21

Provenance Private Collection, New York (acquired directly from the artist) Acquired from the above by the present owner Literature Brian Donnelly, et. al., KAWS: 1993-2010, New York, 2010, p. 204 (illustrated, p. 205; dated 2005)

Painted in 2004, KAWS’s playfully irreverent UNTITLED (FATAL GROUP) is exemplary of the artist’s unique visual lexicon that deconstructs the division between popular culture and fne art. Composed on an immersive scale akin to the grand tradition of history or myth painting, this enigmatic work evinces KAWS at his most technically accomplished and conceptually resolute. Painted with such perfected clarity that there is no trace of the artist’s hand, the careful balance of block colors and monotone shadows harnesses an emotive nostalgia that supports KAWS’s longstanding project of appropriating children’s cartoon characters. The present work refgures the cast of the animated series The Fat Albert Show with their heads composed in the artist’s trademark cross-eyed skulls. Reading like a movie poster without text, this image provides an entrancing scene that challenges the artifce of familiar mass media images and a saturated contemporary visual culture.

Frans Hals, Banquet of the Ofcers of the St. Hadrian Civic Guard Company, 1627. Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, Image Universal Images Group/Art Resource, NY

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 22

Andy Warhol, Last Supper, 1986. Private Collection, Artwork © 2018 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

With UNTITLED (FATAL GROUP), KAWS alludes to the historic genre of the group portrait that was popularized in 16th and 17th century Europe, but, rather than depicting nobility, he selects a familiar image from children’s entertainment. Running from 1972 to 1985, The Fat Albert Show was a popular animated television show for children. Inspired by cartoon imagery, KAWS essentially inserts himself into a long tradition of appropriation within a fne art context: from Marcel Duchamp’s infamous “R. Mutt” signature on his 1917 rendition of Fountain, through to Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans and the photographic appropriation of The Pictures Generation. Yet, rather than re-contextualizing faithful copies of an original, KAWS interprets the Fat Albert cast in his own, highly distinct visual language that echoes Michael Auping’s observation that “KAWS is not just referring to pop culture, he is making it” (Michael Auping, “America’s Cartoon Mind”, KAWS: WHERE THE END STARTS, exh. cat., Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, 2016, p. 63). KAWS, who like Warhol began his career as an illustrator, takes appropriation and reworks it into a mutable or evolutionary form of art. This impulse stems from his early career as a grafti artist when he would intervene on billboards, fashion ads and photo booth advertisements, modifying photographic images so skillfully that his brushstroke-free additions would

22/10/18 09:21

appear as if they were part of the original imagery. This seamless intrusion of his own aesthetic continues in the present work, where the distinction between original source and the artist’s additions are completely dissolved in a unifed surface. KAWS has remarked that he “…wanted to work within the language of the ad, to form a dialogue” (KAWS, quoted in KAWS: WHERE THE END STARTS, exh. cat., Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, 2016, p. 27). As in his earlier grafti days, he has painted X’s into the eyes of these fgures, giving them an empty appearance but also marking them with the moniker of his Generation X. KAWS’s frequent crossover to cartoons positions him as the most recent epitome within a lineage of American artists engaging with graphic art and cartoon illustrations. Cartoons served as an important platform for artists such as Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Ad Reinhardt, and Philip Guston to hone their drafsmanship and compositional skills, but also served as a source of inspiration for Pop artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein to launch their careers. This decade-long

Fat Albert and His Friends: Fat Albert’s Halloween Special, 1977. Image AF archive/Alamy Stock Photo

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 23

Roy Lichtenstein, Look Mickey, 1961. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Artwork © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

development, as poet Robert Duncan has suggested, is “the evolution of the Jungian cartoon mind… The cartoon is our [Americans’] subconsciousness acted out in the public” (Rubert Duncan, quoted in Michael Auping, “America’s Cartoon Mind”, KAWS: WHERE THE END STARTS, exh. cat., Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, 2016, p. 65). KAWS seems to echo this sentiment, choosing cartoons because they inherently act out human emotions, distilled and ofen simplifed to their partly abstracted forms and tropes. As Michael Auping observed of KAWS’s paintings: “this is existentialism absorbed in a cartoon world” (Michael Auping, “America’s Cartoon Mind”, KAWS: WHERE THE END STARTS, exh. cat., Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, 2016, p. 68). This description appears particularly apt when considering the double-entendre of the work’s parenthetical title “FATAL GROUP”, which strongly opposes the optimism and moralizing didacticism of the Fat Albert series. Here, KAWS strikes a profound discord between the jubilant poses and saccharine composition of the TV show’s characters and the dark allusions to death and danger. He ofers not only a recognition of mortality within an otherwise timeless realm of fantasy, but the realization that not all is what it seems, and that the real world lying behind this cute cartoon curtain is far less utopian, far less easily redeemed by quick moral lessons. Fostering a unique sense of the uncanny, in UNTITLED (FATAL GROUP) KAWS presents the ultimate cultural hybrid and a historic addition to the canon of visual appropriation.

22/10/18 09:22

○

3. George Condo

b. 1957

Dreaming Nude signed and dated “Condo 06” on the reverse. oil on canvas. 72 x 60 in. (182.9 x 152.4 cm.). Painted in 2006. Estimate $600,000-800,000

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 24

22/10/18 09:22

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 25

22/10/18 09:23

Provenance Private Collection, New York (acquired directly from the artist) Private Collection, United States Edward Tyler Nahem, New York Acquired from the above by the present owner

A quintessential example of George Condo’s singular and iconic approach to portraiture, Dreaming Nude, 2006, belongs to the handful of paintings from the artist’s seminal Existential Portraits series that tackle the grand tradition of the reclining nude. Painting entirely from his imagination and art historical memory, Condo synthesizes infuences ranging from Old Master painting to Cubism with a sensibility informed by popular culture, to construct a surreal scene. It is almost as if the languorous nude depicted in the drawing at center has jumped out of its frame to materialize into an otherworldly, distinctly Condoesque creature. Echoing the reclining pose of the drawing, the fgure seductively raises one arm behind her head and holds a glass of red wine in the other. True to Condo’s penchant for exaggeration and distortion, however, the woman’s face has been transformed into a twisted mask of bulbous cheeks, menacing fangs and bulging eyes that meets our scrutiny with a confrontational gaze. Showcasing both Condo’s remarkable draughtsmanship and virtuoso handling of paint, Dreaming Nude set the foundation for the artist’s celebrated Drawing Paintings from 2011 and 2012. The theme of the reclining nude represents a key recurring motif in Condo’s oeuvre since the artist’s emergence as a fgurative painter on the New York art scene nearly four decades ago. Having explored the subject matter in the late 1980s and early 1990s vis-à-vis Picasso’s nudes, in the mid-2000s Condo revisited the genre with a handful of paintings that took as their point of departure Francisco Goya’s La Maja Desnuda, 1795-1800, and Édouard Manet’s Olympia, 1863. Both paintings radically subverted the conventions of a genre that advocated classical ideals of nudity – La Maja Desnuda notably representing the frst work of Western art to display pubic hair and Olympia arguably depicting a visibly nude woman within a contemporary setting whose straightforward gaze confronted the viewer.

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 26

Condo takes these trailblazing works as a point of departure, loosely echoing compositional elements as he constructs a woman who similarly confronts us with a defant stare that implicates the viewer with an attitude that, as Ralph Rugof observed, “defates the voyeuristic impulse in our looking, as well as our tendency to project ourselves into an image. Instead it seems to lay the ground for some kind of exchange in a way that goes back to Manet’s Olympia, and the efect of her confrontational gaze” (Ralph Rugof, George Condo, Existential Portraits, exh. cat., Luhring Augustine, New York, 2006, p. 9). Dreaming Nude is exceptional in Condo’s oeuvre for the way in which it explicitly addresses the loaded history of the gaze through the multiple depictions of reclining nudes: as seen in the foreground; in the framed drawing at center that also features a nude man reminiscent of Condo’s recurring character, the “disapproving butler” named Rodrigo; and yet another picture depicted in the background of that very drawing itself. Ultimately, however, the female nude appears to reclaim her agency.

Top: Francisco Goya, La Maja Desnuda, 1795-1800. Museo del Prado, Madrid, Image Bridgeman Lef: Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863. Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Image Scala/Art Resource, NY Opposite: René Magritte, La condition humaine, 1935. Private Collection, Image Banque d’Images, ADAGP/Art Resource, NY, Artwork © 2018 C. Herscovici, Brussels/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

22/10/18 09:23

117980

Demonstrating Condo’s penchant for exaggeration and distortion, the fgure’s physiognomy confronts us with a threatening gaze reminiscent of Willem de Kooning’s women or the screaming heads in Picasso’s Guernica, 1937 – one that does not merely challenge the male gaze of art history, but in fact attacks it with a jarring, animallike snarl. In its palpable psychological intensity, Dreaming Nude is exemplary of Condo’s approach to portraiture as a type of “Psychological Cubism”. Just like Picasso embraced multiple viewpoints in his cubist portraits of his muses – which Condo slyly mimics in the drawing at center – Condo incorporates a multitude of extreme mental vicissitudes. Dreaming Nude is one of the most conceptually arresting paintings in Condo’s oeuvre for the way in which it speaks to its own condition of being a painted representation. Echoing René Magritte’s surrealist strategies, Condo achieves this not only by the mise-en-abyme of multiple pictures of reclining nudes, but also through the confetti of white dots which create the trompe-l’œil efect of a starry sky when they hover in front of the blue wall, yet simultaneously appear like snowfakes when they accumulate into little mounds on the woman’s body. Destabilizing notions of illusion and reality, Dreaming Nude masterfully fuses a century-old subject with the distorted geometric perspectives of Cubism and the trompe-l’œil of Surrealism to delve into the existential depths of the human psyche.

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 27

22/10/18 09:23

The Legacy of Joan Miró Few artists have shaped the scope of art in the 20th century more than Joan Miró. Born in Barcelona in 1893, Miró emerged as an artist in interwar Paris, forging a unique and uninhibited path. His dream-like worlds, composed of whimsical lines and biomorphic shapes foating against indeterminate, monochromatic grounds, represented a wholly new pictorial space borne from the depths of the unconscious. Though Miró was embraced by Dada and the Surrealist avantgarde, he rejected afliation with any one movement in his relentless pursuit of pushing the frontiers of abstraction into unexpected poetic new pastures. In this, Miró was joined by another titan of modern art—Alexander Calder, the American-born artist who was forging ahead with his revolutionary sculpture at the same time in 1920s Paris. Their frst meeting in 1928 was the beginning of an intense and lasting friendship, one that also fostered cross-fertilization of artistic ideas. As Calder noted, “Well the archaeologist will tell you there’s a little bit of Miró in Calder and a little bit of Calder in Miró” (Alexander Calder, quoted in Calder/Miró, exh. cat., Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/ Basel, 2004, p. 28). Sharing a similar vision and fascination with cosmological relationships, the two artists purged the last remnants of illusionism from their respective mediums through their rhythmic evocations of line and color. Even afer Calder returned

to the United States in 1933 and World War II splintered their communication, the two artists remained deeply engaged with each other’s artistic developments. Miró’s far-reaching infuence is undeniable in the annals of post-war art; beyond his impact on contemporaneous artists such as Calder, his insistence on automatism, painterly materiality as well as his attack on convention provided fertile ground for a new generation of artists seeking a ground zero in art in the immediate wake of World War II. For the Abstract Expressionist painter Robert Motherwell, Miró’s emphasis on automatism and painterly materiality provided important cues in his development of an abstract art ftting for the concerns of the age. Born in Washington in 1915, Motherwell held a deep admiration for Miró from early on, likely learning of the Catalan artist during his study abroad in France in 1938 and 1939. Fully devoting himself to art in 1940 under the mentorship of Meyer Shapiro at Columbia University in New York, who notably introduced him to artists such as Alexander Calder, Motherwell pursued an in-depth study of Miró’s work. Motherwell’s encounter with Miró’s art at The Museum of Modern Art’s 1941 retrospective and at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in 1945 was incredibly formative, his

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 28

Above: Joan Miró in his Barcelona studio, 1931. Image © 2018 Successió Miró/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris Lef: Portrait of Robert Motherwell by Ugo Mulas, 1967. Image © Ugo Mulas Heirs

22/10/18 09:24

Right: Alexander Calder in his studio, 1968. Image © Horst TAPPE Fondation/Bridgeman

in early 1948. Towards the end of that year, he made his frst trip to Paris where he would visit Miró in his studio. Seeing Miró’s work in person, particularly his collages, had an incredible impact on Burri. Fascinated by the older artist’s use of unconventional materials such as burlap, sand and tar paper, fabric and nails, among others, Burri embarked upon the development of his unprecedented material realism inspired by the realities of his post-war, industrial context.

Below: Alberto Burri in his studio, Grottarossa, Rome, 1956. Image by Tony Vaccaro/ Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Miró died on December 25, 1983, in Palma de Mallorca, Spain. And yet his singular legacy continues to live on—not just in his masterpiece Femme dans la nuit, 1945, but also in Alexander Calder’s Conique noir, 1972–1973, Alberto Burri’s Grande legno e rosso, 1957– 1959, and Robert Motherwell’s Open No. 153: In Scarlet with White Line, 1970. Seen together, they reveal the formal and conceptual breadth of an artist whose anarchic and radically modern vision spurred some of the most seminal artists of the past century to ever greater heights.

deep afnity with the artist leading him to include Miró not only in the 1947 artistic and literary magazine Possibilities that he co-edited, but also extensively writing on his oeuvre throughout his career. As he proclaimed in 1953, “I think Miró is the most important post-Picasso fgure in Europe” (Robert Motherwell, “Is the French Avant-Garde Overrated”, 1953, in Dore Ashton, ed., The Writings of Robert Motherwell, Berkeley, 2007, p. 167). On the other side of the Atlantic, Miró’s anarchic vision of moving “beyond painting” similarly ofered critical impulses for Italian-born artist Alberto Burri. Though the same age as Motherwell, Burri had only turned to art making in the mid-1940s as an autodidact—taking up painting during his internment as a prisoner of a war and leaving his medical practice behind upon settling in Rome in 1946. While Burri initially worked in a fgurative style, seeing black-and-white reproductions of Miró’s work, in addition to that of Paul Klee, led him to embark upon his frst abstract compositions

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 29

22/10/18 09:24

Property from an Important European Private Collection

4. Joan Miró

1893-1983

Femme dans la nuit signed, titled and dated “Miró 22-3-45 “femme dans la nuit”” on the reverse. oil on canvas. 51 1/8 x 64 in. (129.9 x 162.6 cm.). Painted on March 22, 1945. Estimate $12,000,000-18,000,000

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 30

22/10/18 09:26

01_NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_FO1_Miro_30-31.indd 1

22/10/18 19:11

01_NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_FO1_Miro_30-31.indd 2

22/10/18 19:11

01_NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_FO1_Miro_30-31.indd 3

22/10/18 19:11

Provenance Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York (inv. no. 1879) (acquired directly from the artist by 1947) Carlo Bilotti, Rome and New York (acquired from the above on January 18, 1972) Acquavella Galleries, Inc., New York (acquired from the above shortly aferwards) Acquired from the above by the family of the present owner circa 1973, and thence by descent Exhibited Paris, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Joan Miró, June November 1962, no. 77 New York, Acquavella Galleries, Inc., Joan Miró, October 18 November 18, 1972, no. 49, n.p. (illustrated on cover) Lugano, Museo d’Arte Moderna, Passioni d’Arte: da Picasso a Warhol, Capolavori del collezionismo in Ticino, September 22 – December 8, 2002, pp. 214, 322 (illustrated, p. 215) Riehen/Basel, Fondation Beyeler, Calder/Miró, May 2 September 5, 2004, no. 136, pp. 20, 255, 291 (illustrated, p. 212) Literature Jacques Dupin, Miró, Paris, 1961, no. 651, p. 355 (illustrated, p. 534) Jacques Lassaigne, Miró, Geneva, 1963, p. 139 (illustrated, p. 94) Jacques Dupin and Ariane Lelong-Mainaud, Joan Miró: Catalogue raisonné. Paintings, vol. III, Paris, 2001, no. 751, p. 75 (illustrated)

In Joan Miró’s Femme dans la nuit, 1945, a female creature is shown on the lef-hand side of a large canvas while the rest of the composition is flled with an array of characters, signs and glyphs. At the top is a black star, radiating against the light background. These elements, rendered with painstaking precision, have been contrasted with more freely rendered elements: caterpillar-like squiggles that wind through the picture, the loops of their meandering forms containing spots of color—green, mauve and orangey yellow. The resulting composition, one that rhythmically pulses with life, is comprised of elements that are found throughout the entire cycle of 14 paintings Miró conceived in 1945.

01_NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_FO1_Miro_30-31.indd 4

Joan Miró in 1947, photographed by George Platt Lynes. Image Bridgeman, Artwork © 2018 Successió Miró/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Created against the backdrop of World War II, Femme dans la nuit forms part of this ambitious series of 14 large paintings, each featuring Miró’s signature ideograms on an atmospheric white background that the artist undertook between January 26 and May 7, 1945 – the fnal work painted the same day as Germany signed the unconditional surrender in Reims. Painted on March 22, Femme dans la nuit is an important example from this group, its singular position refected in its inclusion in the artist’s seminal retrospective at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris in 1962. Other examples from the series now reside in important institutional collections including the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Bufalo, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf and the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid.

22/10/18 19:11

Miró, quoted in Hershell B. Chipp, ed., Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics, Berkeley, 1984, p. 434). It was this series, coupled with the tragic passing of the artist’s mother on May 27, 1944 that brought about an infection point in the artist’s work, laying the foundation for him to undertake his most ambitious body of work since the onset of the war. The Turning Point of 1945

Joan Miró, Ciphers et constellations amoureux d’une femme, 1941. The Art Institute of Chicago, Image Art Resource, NY, Artwork © 2018 Successió Miró/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Femme dans la nuit: An Heir to Miró’s Constellations Femme dans la nuit was acquired in 1947 by Pierre Matisse, Miró’s most signifcant art dealer since 1933. The son of Henri Matisse, Pierre had moved to New York and set up an esteemed gallery to introduce primarily European avant-garde artists to the American market. In spite of wartime restraints, it was at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in January 1945 that Miró’s earliest images inspired by World War II were frst exhibited to unprecedented acclaim – the so-called Constellations, modestly scaled works on paper primarily in gouache. Discussing the Constellations and subsequent works a few years afer Femme dans la nuit was painted, Miró explained: “The night, music and the stars began to play a major role in suggesting my paintings. Music had always appealed to me, and now music in this period began to take the role poetry had in the early twenties – especially Bach and Mozart when I went back to Mallorca afer the fall of France” (Joan

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 31

Coinciding with the exhibition’s success in New York, Miró chose to undertake a second, concluding cycle of works inspired by the war, doing so with the belief that these would become his magnum opus. Since 1937, nothing but war had featured in Miró’s work; its trials had completely sidetracked not just his art career but his personal life as well. Writing to Georges Raillard, Miró exclaimed, “I remember very well this time of fascism. I took refuge here in Palma, and I said to myself: ‘My old man, you’re done! You’re going to go to sleep on a beach and draw in the sand with a cane. Or you’ll make drawings with the smoke of a cigarette... you will not be able to do anything else...all is ruined!’ I had this impression clearly at the time of Hitler and Franco” (Joan Miró, quoted in Ceci est la couleur de mes rêves. Entretiens avec Georges Raillard, Paris, 1977, p. 75). Writing to Roland Penrose in retrospect, he explained of his psyche at the time, “I believed in the inevitable victory of Nazism, and that everything which we loved and which constituted our reason for being was forever thrown into the abyss” (Joan Miró, quoted in Lilian Tone, “The Journey of Miró’s Constellations”, MoMA, no. 15, Autumn 1993, p. 2). When the war did ultimately end in May 1945 and Miró was able to consider the importance of the series of works he began earlier that year, conceived in the darkest hours when peace had seemed so far away, he understood them to be a watershed moment, not just in his own art, but also for the future of art. He was immediately inspired to explore the possibility of exhibiting his war works in totality. Writing to Christian Zervos less than two months afer Femme dans la nuit was painted, Miró explained, “during this period of time one had to enter into action in one manner or another, or blow one’s brains out; there was no choice…This exhibition

22/10/18 09:28

of a line “that goes out for a walk, so to speak, aimlessly for the sake of the walk” (Paul Klee, in Jurg Spiller, ed., Paul Klee Notebooks, Volume 1: The Thinking Eye, London, 1961, p. 105). A Picture for a Newborn Humanity

Joan Miró photographed by Joanquim Gomis, 1942. Image © Fundació Joan Miró

should not be considered as a simple artistic event, but an act of human import, by reason of being an oeuvre realized during this terrible time when they wanted to deny all spiritual values and to destroy all that man holds precious and worthy in life” (Joan Miró, quoted in Lilian Tone, “The Journey of Miró’s Constellations”, MoMA, no. 15, Autumn 1993, p. 4). The large canvases that Miró painted in 1945 saw him address the legacy of his artistic contemporary and friend Wassily Kandinsky, who had declared “my stories…are not narrative or historical in character, but purely pictorial” (Wassily Kandinsky, quoted in Kandinsky in Paris: 1934-44, exh. cat., Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1985, p. 30). Just before Miró fed France, both had been living in Varengeville when Miró created his frst Constellations in 1939. At the end of 1944, just before Miró commenced his white paintings, Kandinsky had died. Miró was taking up the mantle – all the more so as Kandinsky’s old friend Paul Klee had also died four years earlier. Miró had never met Klee, but his discovery of the Swiss artist’s pictures earlier in his career had been a revelation, particularly Klee’s notion

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 32

This 1945 series represented Miró’s dramatic return to painting on canvas afer several years of focusing on prints, drawings and watercolors due to the dearth of opportunities to produce or market works conceived on the ambitious scale he would undertake with this cycle of paintings. These works, along with the notebooks that he kept during the war, act as a repository of sorts from which to excavate his source inspiration for the paintings of 1945. Miró’s notebooks indicate the extent to which he planned Femme dans la nuit and its sister-works during the war years, while also revealing how much the concepts evolved. While Miró originally intended to use earlier drawings as his inspiration for the series, he explained, “The frst stage is free, unconscious; but afer that the picture is controlled throughout, in keeping with that desire for disciplined work I have felt from the beginning” (Joan Miró, quoted in Hershell. B. Chipp, ed., Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics, Berkeley, 1984, p. 435). Discussing these intended paintings in his notebooks, Miró wrote in terms that clearly relate to Femme dans la nuit: “the lines that I shall draw in over it [sic] should be very sharp, the poignant outcries of the soul, the whimperings of a new-born world and a new-born humanity arising out of the ruins and rottenness of today” (Joan Miró, quoted in Gaetan Picon, ed., Joan Miró: Catalan Notebooks, London, 1977, p. 124). Miró led a quasi-monastic existence during this period, recalling his time in Montroig during World War I, when he compared himself to Dante in a letter to E.C. Ricart. This is all the more apt as Femme dans la nuit recalls Dante’s Paradiso: with the woman’s entrance into a clear world of light, the picture echoes Beatrice leading the poet into the Empyrean realm. This is evidenced in Femme dans la nuit where Miró deliberately distilled his visual iconography and lent it a greater impact by presenting it against the atmospheric white backdrop.

22/10/18 09:28

Wassily Kandinsky, Untitled, 1940. Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, Image © CNAC/ MNAM/Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY, Artwork © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

dominate: gone is the all-over decoration of the earlier Constellations. Refning the iconography of his earlier series, the works of 1945 avoid density in favor of allowing more emphasis on the individual elements. The various forms in Femme dans la nuit, and in particular the dumbbell-like shapes linked by lines, take on the rhythmic appearance of musical notations, adding a pulsing visual cadence to the composition. And yet they also have a distinctly fgurative reading within the composition as well as specifcally address the worst horrors of the war: bombs raining from airplanes. Miró speaks of capturing this terror in his notebooks from the period, “up in the sky a plane done like a bird of fantastic shape in the spirit of Bruegel or Hieronymus Bosch…” (Joan Miró, quoted in Gaetan Picon, ed., Joan Miró: Catalan Notebooks, London, 1977, p. 33). Miró’s Guernica

These felds fnd their precedent in the monochromatic felds of color, predominately in blue, yellow, and brown, which the artist established in the mid-1920s that had become a signature of sorts. It is no surprise then, that his dramatic return to painting afer years working on a more diminutive scale would inspire the artist to revisit his revolutionary mode of covering the ground of his canvases that was quintessential to his work at the height of his career in the years before the war. The uneven feld of white paint succeeds in projecting a space for his main pictorial elements to

Most, if not all of the works featuring these dumbbells—and all those featuring the rough-hewn squiggly creatures—date from the World War II period. Evoking bombs and planes, air fraught with potential danger, they recall the essential theme of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica as well as René Magritte’s Le drapeau noir, both 1937. This context is all the more pointed as Femme dans la nuit was painted at a time of the most vigorous bombings by the Allied and Axis forces in Europe and Asia in early 1945.

Paul Klee, Insula Dulcamara, 1938. Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Image Bridgeman, Artwork © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 33

22/10/18 09:29

“The night, music and the stars began to play a major role in sugesting my paintings.” Joan Miró

The female fgure who dominates Femme dans la nuit echoes the form in El segador, 1937, a colossal large-scale mural of a Catalan peasant Miró created for the Spanish Pavilion at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, where it hung near Picasso’s Guernica. This was a protest picture, a cry of anguish about the aerial bombing of Spain. Miró’s relentless ambition had him musing on how he would go beyond what Picasso presented in 1937, writing around 1940, “let these canvases be in a highly poetic and musical spirit, done without any apparent efort, like birdsong, the uprise of a new world or the return to a purer world, with nothing dramatic about them and nothing theatrical, full of love and magic, in their conception as unlike Picasso’s canvases as possible, for his represent the end and dramatic summing up of an era with all its impurities, contradictions and expedients” (Joan Miró, quoted in Gaetan Picon, ed., Joan Miró, Le Faucheur, 1937. Artwork © 2018 Successió Miró/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Image Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY, Artwork © 2018 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 34

22/10/18 09:29

“The solitary life at Ciurcana, the primitivism of these admirable people, my intensive work, and especially, my spiritual retreat and the chance to live in a world created by my spirit and my soul, removed, like Dante, from all reality... I have withdrawn inside myself, and the more sceptical I have become about the things around me the closer I have become to God, the trees, the mountains, and to friendship. A primitive like the people of Ciurana and a lover of Dante.” Joan Miró to Enric Cristofol Ricart, August 1917

Joan Miró: Catalan Notebooks, London, 1977, p. 116). Eight years later, in Femme dans la nuit, this ambiguous and engaging image of doom and defance retained much of its currency. While light and optimism were tentatively raising their heads in this luminous sequence of 1945, there is nonetheless a keen awareness of the toll of war, made all the more vivid by the presence of a sky laden with weighty forms. In many ways, the woman in Femme dans la nuit and several of its sister pictures can be seen as an analogue for the screaming and wailing fgures of Picasso’s Guernica.

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 35

René Magritte, Le drapeau noir, 1937. National Galleries of Scotland, Artwork © 2018 C. Herscovici, Brussels/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A Timeless Legacy The connections across the years between Femme dans la nuit with the earlier El Segador and the Constellations series provide an insight into Miró’s working practice, whereby chance marks served as a springboard for an initial concept that he would elaborate over time. The marks in those paintings and in Femme dans la nuit all recall ancient cave art while also reverberating with the concerns of the existentialists who were coming to the fore in intellectual circles in Paris and elsewhere. At the same time, the “ideograms” that punctuate Miró’s works from the 1920s onwards ofen echoed the letters from his own name—his signature—using them as the seed for a composition. This was especially true with his initial “M”. In The Potato, for example, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the white portion of a fgure’s hand is emblazoned with an “M” that terminates with a curlicue that echoes the “o” from the end of his name. While these letters occasionally punctuated Miró’s paintings over the years, in the series of pictures from the end of the World War II to which Femme dans la nuit belongs, there is a remarkable density of their occurrence. In Femme dans la nuit itself, the more freeform element

22/10/18 09:30

Joan Miró, The Potato, 1928. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Image Art Resource, NY, Artwork © 2018 Successió Miró/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

that loops across the upper part of the canvas, which doubles as a Bosch-like bomber, also appears to contain at least an “M” and an “o”. This revealed Miró entwining his entire identity with the process of painting, an art form to which he was now returning with gusto. And the centrality of his name was all the more apt as it appears linked to the Spanish and Catalan verb “mirar” —to look. The impact of Miró’s paintings was seemingly immediate, where the insights expressed in these paintings of war were recognized, both in Europe and in the United States. Post-war paintings by Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell all share the same anguish and unprecedented graphic universality through abstraction that is so intensely presented in

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 36

this work. It is through works such as Femme dans la nuit that we can associate Miró more so with the generation of artists that would succeed him than with the previous generation who came to prominence before the war. And this becomes apparent why upon reading Miró’s own hopes for his art at that time – he was looking forward to envision a new art, conceived “as a good poem or the breath of air or the fight of a bird, and just as fne and pure”, and in doing so, he shaped a new generation of artists (Joan Miró, quoted in Gaetan Picon, ed., Joan Miró: Catalan Notebooks, London, 1977, p. 116). Looking at Femme dans la nuit, one can see that Miró’s example found fresh soil in the form of Motherwell in particular, as evinced in the freedom, lyricism and

22/10/18 09:31

“I remember very well this time of fascism. I took refuge here in Palma, and I said to myself: ‘My old man, you’re done! You’re going to go to sleep on a beach and draw in the sand with a cane. Or you’ll make drawings with the smoke of a cigarette... you will not be able to do anything else... all is ruined!’” Joan Miró

restraint of works such as Open No. 153 of 1970. It is easy to understand why Motherwell himself would heap praise upon Miró in terms that also apply to his own work: “A sensitive balance between nature and man’s works, almost lost in contemporary art, saturates Miró’s art, so that his work, so original that hardly anyone has any conception of how original, immediately strikes us to the depths. No major artist’s atavism fies across so many thousands of years (yet no artist is more modern)” (Robert Motherwell, “The Signifcance of Miró”, in Dore Ashton & Joan Banach, eds., The Writings of Robert Motherwell, Berkeley, 2007, p. 188). Alexander Calder with Dolores, Pilar, and Joan Miró, Varengeville, summer 1937. Image Hans Hartung/ Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource, NY

Detail of present work. This mountain-looking ideogram is illustrated in Miró’s notebooks from the war years where he noted it was to represent the “scream of a swallow”.

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 37

22/10/18 09:31

Ownership of Other Paintings in the Series

Femme dans la nuit, March 1, 1945. (Cat. no. 748) Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Femmes et oiseaux dans la nuit, February 12, 1945. (Cat. no. 746) Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf

Femme et oiseau dans la nuit, January 26, 1945. (Cat. no. 743) Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona

Femme rêvant de l’évasion, February 19, 1945. (Cat. no. 747) Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona

Femme et oiseaux dans la nuit, March 8, 1945. (Cat. no. 749) Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Bufalo Personnage et oiseau dans la nuit, February 5, 1945. (Cat. no. 745) Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

Additional paintings in the series are in prominent private collections including Mrs. Emily Rauh Pulitzer (promised gift to the Harvard Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge), (Cat. no. 752); The Morton G. Neumann Family Collection (Cat. no. 753); and The Nahmad Family Collection (Cat. no. 754).

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 38

Opposite: Joan Miró, 1950s. Image Album/Art Resource, NY, Artwork © 2018 Successió Miró/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

22/10/18 09:31

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 39

22/10/18 09:31

Property of an Important Belgian Collector

5. Alexander Calder

1898-1976

Conique noir incised with the artist’s monogram and date “CA 73” on the upper lef white element; further incised with the artist’s monogram and date “CA 72” on the lef side of the base. sheet metal, wire and paint. overall 42 1/2 x 39 x 25 in. (108 x 99.1 x 63.5 cm.). Executed in 1973, this work is registered in the archives of the Calder Foundation, New York, under application number A11622. Estimate $1,200,000-1,800,000

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 40

22/10/18 09:32

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 41

22/10/18 09:32

Provenance Galerie Maeght, Paris Waddington Galleries, London (acquired from the above in June 1982) Acquired from the above by the present owner on November 11, 1982

Celebrating a lifetime of innovation, Alexander Calder’s Conique noir, 1973, is an exceptional example of the artist’s investigation of space, volume and color. A distinct work within Calder’s oeuvre for its conical shaped base, it expands upon earlier works such as The Cone, 1960, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Bufalo, and Conique rouge, 1972. As with these works, Calder has fused his iconic sculptural archetypes of the stabile and the mobile into a singular, impeccably balanced work in his signature palette of black, white, and red. The stabile consists of a conical, void shape, its black

Launch of the Apollo 17 mission, 1972. Image Oxford Science Archive/Print Collector/Getty Images

exterior revealing a rich interior that is painted in a fery red. Resting atop the cone’s pointed zenith is the mobile portion – a red horizontal rod which balances large white biomorphic discs on either side via delicate wire rods.

Alexander Calder, The Cone, 1960. Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Bufalo, NY, Image Art Resource, NY, Artwork © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 42

“Just as one can compose colors, or forms,” Calder wrote in 1933, “so one can compose motions” (Alexander Calder, 1933, quoted in Jed Pearl, Calder, The Conquest of Time, New York, 2017, p. 507). It was in 1930 that Calder made the radical transition from his circus-themed wire fgures to abstract constructions, which would set in motion his kinetic revolution of sculpture. Calder developed his artistic sensibility in the heady climate of 1920s Paris, where he became a fully-fedged member of the European art world. It was there that he encountered the work of Joan Miró and Piet Mondrian. The sight of seeing Mondrian’s colored shapes foating unframed on the wall inspired Calder to begin his own experiments of abstraction, but it was perhaps above all his deep

22/10/18 09:32

Alexander Calder and Joan Miró at the opening of Calder’s retrospective at Galerie Maeght, Saint Paul De Vence, April 3, 1963. Image © AGIP/Bridgeman Images

friendship and dialogue with Miró that helped him elaborate and develop his trailblazing ideas concerning balance and motion over the years. It is indeed telling that when Calder’s mobiles were exhibited at his second show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in 1936, critics were quick to point out the parallels to Miró’s art: “They are very much like Miró abstractions come to life” (Emily Genauer, “Calder’s Mobiles”, New York World-Telegram, February 15, 1936). Indeed, with its organic shapes, whimsical lines and allusion to the imaginary, Conique noir appears like the sculptural realization of the organic forms teeming in Miró’s fantastical compositions. Though Miró also briefy focused on creating sculptures during his hiatus from painting in 1931, Calder pushed his objects into poetic regions that no other artist before him had ventured into – going even beyond Pablo Picasso’s sculptures of 1928 that were lauded as “drawing in

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 43

space”. Leaving the two-dimensional pictorial surface behind, Calder blazed ahead into the four-dimensional realm, adding time to the classic three dimensions. Equipped with his impeccable engineering skills, he crucially invented the two sculptural archetypes of the “stabile” and the “mobile” in the early 1930s that he would continue to elaborate on and refne throughout the ensuing four decades. Conique noir accomplishes Calder’s goal of expressing both stillness and dynamic movement in one artwork by fusing the stabile and mobile, a combination Calder had started consistently exploring since the 1940s. As he explained, “The mobile has actual movement in it itself, while the stabile is back at the old painting idea of implied movement. You have to walk around a stabile or through it – a mobile dances in front of you” (Alexander Calder, 1960, quoted in Motion-Emotion: The Art of Alexander Calder, exh. cat., O’Hara Gallery,

22/10/18 09:32

New York, 1999, n.p.). While a similar push and pull permeates Conique noir, its conical stabile heightens the efect of implied movement to the extent that it appears to lif above the ground. The cone is a rare shape to occur in Calder’s oeuvre. While the shape featured as a solid wooden form in Cône d’ébène, 1933, widely regarded as one of his very frst mobiles, it appears that Calder only started to revisit it some three decades later with the stabile, The Cone, 1960. While that earlier sculpture consisted of two conical portions placed atop of each other, Conique noir and its sister work Conique rouge, 1972, consist of a single sheet of bent metal – giving rise to an unadulterated sense of upward movement. Representing the more intimate pendant to the large-scale commissioned public sculptures Calder created throughout the 1960s until his death in 1976, Conique noir points to Calder’s playful engagement with paraphrased ideas regarding the Space Age. Its dynamism and red interior recalls stabiles such as Rocket, 1964, and particularly Obus, 1972, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., which presented the rough shape of a rocket launcher with fre-engine red fames spurting from its side. Calder’s imaginative works ofen seem to exude a whimsical optimism, yet, as recent scholarship has pointed out there are also oblique political undertones that refect Calder’s increasingly public anti-war activism in the 1960s and 1970s. Seen in this light, intriguing parallels begin to arise between Conique noir and Miró’s Femme dans la nuit, 1945, a whimsical yet deeply existential distillation of pure line and color. Testimony to a lifetime of innovation, Conique noir epitomizes Calder’s pioneering mastery of a new genre – one which by the time of the work’s creation had frmly cemented his stature as one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century.

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 44

22/10/18 09:33

“I want things to be diferentiated [within my work]. Black and white are frst—then red is next... I love red so much that I almost want to paint everything red. I often wish I’d been a fauve in 1905.” Alexander Calder

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 45

22/10/18 09:33

Property from a Distinguished European Collection

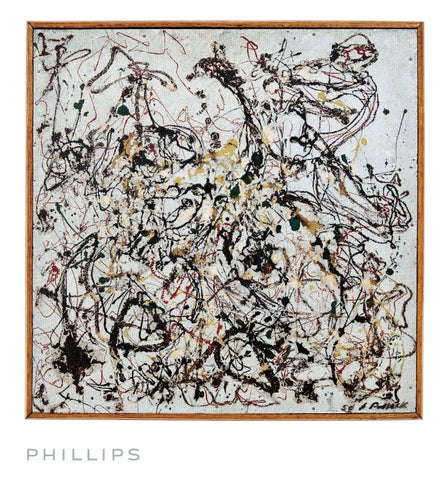

6. Alberto Burri

1915-1995

Grande legno e rosso signed and dated “Burri 57-59� on the reverse. wood, acrylic and combustion on canvas. 59 x 98 3/8 in. (150 x 250 cm.). Executed in 1957-1959. Estimate $10,000,000-15,000,000

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 46

22/10/18 09:33

03_NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_FO2_Burri_46-47_BL.indd 1

22/10/18 19:10

03_NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_FO2_Burri_46-47_BL.indd 2

22/10/18 19:10

03_NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_FO2_Burri_46-47_BL.indd 3

22/10/18 19:10

Provenance Galleria La Tartaruga, Rome Acquired from the above by the family of the present owners in the early 1960s, and thence by descent Exhibited Rome, Galleria La Tartaruga, Afro, Burri, Capogrossi, Matta, started December 5, 1957 Venice, XXIX Biennale Internazionale d’Arte, 1958, no. 258 (bears label on the stretcher, not listed in the exhibition catalogue) São Paulo, Museu de Arte Moderna, Artistas Italianos de Hoje na 5a. Bienal do Museu de Arte, September - December 1959, no. 24 Rio de Janeiro, Museu de Arte Moderna, Burri, Somaini, Vespignani: três artistas italianos premiados na 5a. Bienal de São Paulo, March - April 1960, no. 11 New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; Dusseldorf, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Alberto Burri: The Trauma of Painting, October 9, 2015 - July 3, 2016, no. 41, p. 184 (illustrated, pp. 192-193) Literature Mario Pedrosa, “Artes visuals. Burri etc. (III)”, Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, April 7, 1960 Rafaelle Carrieri, Pittura e scultura d’avanguardia in Italia 1890-1960, Milan, 1960, n.p. (illustrated) “Untitled”, L’Œil, no. 94, Paris, October 1962, p. 49 (illustrated)

Cesare Brandi, ed., Burri, Rome, 1963, no. 69, n.p. (illustrated) Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, Le arti oggi in Italia, Rome, 1966, p. 71 (illustrated) Franz Meyer, “Macchia e materia: Fautrier, Wols, Dubufet, Burri, Tapies”, L’arte moderna, no. 105, vol. XII, Milan, 1967, p. 224 (illustrated) Nello Ponente, “La crisi dell’immagine e della forma”, L’arte moderna, no. 93, Milan, 1967, p. 150 (illustrated) Maurizio Calvesi, Le grandi monografe: Pittori d’oggi, Burri, Milan, 1971, p. 22 (illustrated, p. 42) Marisa Volpi Orlandini, “Alberto Burri”, Storia dell’Arte, nos. 38-40, vol. II, Florence, June - December 1980, p. 407 Luciano Caramel and Francesco Poli, Storia Universale dell’Arte, vol. IX, Milan, 1985, p. 223 (illustrated) Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini, ed., Burri: Contributi al Catalogo Sistematico, Città di Castello, 1990, no. 605, p. 146 (illustrated, p. 147) Giuliano Serafni, “Burri”, art e dossier, no. 62, Florence, November 1991, p. 44 (illustrated) Gloria Vallese, “E Lucio Fontana fece il primo taglio”, Arte, no. 215, Milan, February 1991, p. 79 (illustrated) Giuliano Serafni, Burri: La misura e il fenomeno/The Measure and the Phenomenon, Milan, 1999, p. 53 Bruno Corà, ed., Alberto Burrio: opera al nero, Cellotex 19721992, exh. cat., Galleria dello Scudo, Verona, 2012, pp. 214-215 Bruno Corà, ed., Burri: General Catalogue, Painting, 19581978, vol. II, Perugia, 2015, no. 725, p. 40 (illustrated, p. 41) Bruno Corà, ed., Burri: General Catalogue, Chronological Repertory, 1945-1994, vol. VI, Perugia, 2015, no. 725, p. 129 (illustrated)

Installation view of Alberto Burri: The Trauma of Painting, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, October 9, 2015 – January 6, 2016 (present work exhibited). Image Kristopher McKay, Artwork © 2018/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

03_NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_FO2_Burri_46-47_BL.indd 4

22/10/18 19:10

Monumental and absorbing in scale, Alberto Burri’s Grande legno e rosso from 1957-1959 stretches over eight feet in breadth. This colossal painting features the combination of wood and fre that Burri had only recently introduced into his work, placing it at the vanguard of his oeuvre. According to the catalogue raisonné of Burri’s work, this is the largest of the Legno e rosso works that he created, hence its name; additionally it is one of only two to incorporate combustion, the other being a fraction of the size. A picture of exceptional quality, it has been in the same family’s ownership since its acquisition from the acclaimed Galleria La Tartaruga, Rome, shortly afer its execution. The importance of Grande legno e rosso is further indicated by its inclusion in the critically-acclaimed 2015 retrospective of Burri’s work held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Afer that exhibition, the presentation of this picture at auction marks only the second occasion it has been shown publically since 1960, shortly afer it was completed. Grande legno e rosso demonstrates why Burri’s works chimed so well with the atmosphere of post-war Europe. The continent had been ravaged by the Second World War. Old hierarchies had been toppled. This was the age of Existentialism and Abstract Expressionism. Establishing his ground-breaking career in Rome and New York in the early 1950s, Burri’s works appeared to challenge both: his incorporation of “poor” materials such as sackcloth and wood revealed an artist appearing to elevate the humblest of elements into the realm of the artistic, placing them on a previously unthinkable pedestal. Likewise, the techniques that Burri employed,

Alberto Burri, Martedì Grasso, 1956. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Artwork © 2018/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 47

Alberto Burri, Texas, 1945. Private Collection, Artwork © 2018/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

be it the stitching in his Sacchi or the use of fre in works such as Grande legno e rosso, indicated an artist who was fnding new ways of making a mark on the canvas. Burri’s innovations came at the same time as the holes of Lucio Fontana and the drips of the recently-deceased Jackson Pollock. By scorching wood and incorporating it within the confnes of a picture surface, Burri was pushing the boundaries of art to new extremes. In using these materials from the world around him, he was creating seemingly autonomous works that took shards of the real world and reconfgured them in order to eke out a new visual poetry. These works are not representative: they simply are. And in this, their autonomy, they would fnd themselves the unwitting progenitors of a number of subsequent artistic developments both in Italy and abroad, from Arte Povera to Minimalism. Over the course of his ffy-year career, Burri developed his practice through discrete series, each of which was defned by and titled afer the dominant process, material or color. Following his Sacchi series, consisting of collage-like compositions stitched from cast-of linens and burlap material, Burri in the mid-1950s developed his Combustioni and Legni. Adopting materials essential to Italy’s post-war reconstruction and building industry, he utilized materials such as wood veneer and pioneered his new so-called combustion process of burning material.

22/10/18 09:33

“I see beauty and that is all…I am sure that every picture that I make, whatever the material, is perfect as far as I am concerned. Perfect in form and space. Form and space: these are the essential qualities that really count.” Alberto Burri

Alberto Burri in his studio, 1962. Image © Ugo Mulas Heirs

By incorporating fre within the picture surface, Burri could be seen to be taking up the challenge that had been set down by Joan Miró in the years before World War II. “The only thing that’s clear to me is that I intend to destroy, destroy everything that exists in painting,” Miró had declared. Miró, whom Burri had visited in his studio in Paris in 1948, admitted that he was nonetheless constrained by “the customary artist’s tools—brushes, canvas, paints—in order to get the best efects. The only reason I abide by the rules of pictorial art is because they’re essential for expressing what I feel” (Joan Miró, quoted in Margit Rowell, ed., Joan Miró: Selected Writings and Interviews, Cambridge, 1992, p. 116). In Grande legno e rosso and his other works, Burri demonstrated his ability to surpass those limitations. While Miró sought to destroy painting by creating imaginary universes, Burri’s art is grounded in both the past and present. Burri’s striking chromatic palette of red, black and ochre abounds with associations to not just post-war Italy, but also with references to art history – particularly in his use of the color black. The chromatic intensity that Burri achieves by juxtaposing black with fashes of red and in particular reveals his afnity with Michelangelo Caravaggio.

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 48

One of the frst Baroque painters to use black as the main element of his chiaroscuro, Caravaggio introduced a dramatic intensity hitherto absent from religious painting that would pave the way for numerous followers over the centuries. In Grande legno e rosso, the black feld is then not one of absence or functions merely as a background; much more, it is an integral component to achieve Burri’s desired tension between fatness and depth. Burri’s use of black as a bolster for the entire composition achieves a chromatic richness that reveals both his indebtness to the rich canon of Italian painting, and his ability to maneuver beyond its limitations. By the time that Grande legno e rosso was created, Burri had already become an internationally-recognized artist, having gained increasing exposure and acclaim at the beginning of the 1950s. This was in part due to his promotion by the legendary museum director James Johnson Sweeney, who exhibited and acquired his works from an early stage, having been introduced to Burri during a visit to Rome in 1953. By 1957, Burri was participating in shows throughout Europe and the United States. This rise to fame was all the more impressive as it was only during his imprisonment in World War II that he had turned to painting as a vocation, abandoning medicine, his former calling.

22/10/18 09:34

While serving as a prisoner of war in Hereford, Texas, Burri became increasingly focused upon art; although he would later destroy many of the works from this period, he made a point of saving his early landscape, Texas. This work, flled with scorched red and orange and with a high horizon line, can be seen as a forebear for the composition of Grande legno e rosso, where the lower two thirds of the picture are also redolent of the heat and colors of the desert of Texas. This landscape reveals the deeplyingrained sense of proportion that underpinned Burri’s work throughout his life. It is not that Grande legno e rosso refers to the landscape itself, but that the two works share the same fundamental quest for balance within the composition. Burri himself would declare that his pictures contained, “Form and space! That’s it! There is nothing else! Form and space!” (Alberto Burri, quoted in Stefano Zorzi, Alberto Burri. His Thoughts. His Words, 2018, p. 90). For Burri, this particular type of composition would be one to which he would return on a number of occasions, for instance in Martedì Grasso, another painting of almost the same scale which was formerly in the collection of G. David Thompson, and is now in the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. That work features strips of material rather than the wood and band of red paint of Grande legno e rosso, yet their kinship is self-evident. Similarly, Legno SP, 1958, in the Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini, Città di Castello, bears a similarity. Even the tiny Senza titolo, 1956, from the same museum, which measures a mere three and a half inches in breadth, echoes this composition, albeit with the upper horizontal band occupied in that case by a piece of scorched wood. Related compositions had even featured among the Sacchi, the earlier burlap works with which Burri had achieved such notable success. Later examples would pick up these visual rhythms, be it the Legno nero rosso of 1960 which hung next to Grande legno e rosso at the artist’s retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York in 2015, and which appears to have taken up the theme albeit on a similar scale, or the later Cellotex works, which likewise sport similar proportions, harnessed through Burri’s interventions with paint and fberboard. These variations on a similar composition show the elegant sense of equilibrium which Burri sought in his works, turning his selections of unusual materials and techniques to the achievement of a sense of pictorial harmony. It is telling that Burri’s works were known to be admired by Giorgio Morandi, the painter of contemplative still life compositions. Burri himself would sometimes claim that his

NY_TCA_EVE_NOV18_2-63_BL.indd 49

22/10/18 09:34

Caravaggio, Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1598-1599. Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica at Palazzo Barberini, Rome, Image Scala/Art Resource, NY

materials were almost incidental, and that it was the problem of composition that he sought to solve, using wood, sackcloth or iron more because of their aesthetic qualities than any sense of meaning or purpose. Burri nonetheless accepted that his materials had appearances that appealed to him, and this is palpable in his use of wood in Grande legno e rosso. The wood contrasts with the bands and columns of uniform black and red paint, its warp and veins pushed to the fore. Its variations in color and almost marbled appearance add to the composition, becoming a readymade parallel to Pollock’s drips. The wood becomes a part of Burri’s arsenal— or rather his palette. In a rare interview with his friend Stefano Zorzi, Burri spoke in terms that refect his intense focus on composition: “I have fnally found a phrase that mirrors, with absolute fdelity, my conception of painting. It is just a couple of lines by Robert Bridges that I found, if you can believe it, in a scientifc text. He says, ‘Our stability is but balance, and our wisdom lies in masterful administration of the unforeseen.’ This is the foundation of my painting” (Alberto Burri, quoted in Stefano Zorzi, Alberto Burri. His Thoughts. His Words, 2018, p. 17). That element of the “unforeseen” is encapsulated in the increasing interest Burri showed in using fre as a part of his creative process, as is the case in Grande legno e rosso. Where earlier, he had begun to burn paper to create artworks, and would subsequently use fames to melt and make holes in plastic, he took advantage of the