Digital Humanities

PhiloBiblon 2024 n. 4 (mayo) Los manuscritos del Fuero Juzgo: denominaciones antiguas y signaturas modernas

Mónica Castillo Lluch

(Université de Lausanne)

Carmen del Camino Martínez

(Universidad de Sevilla)

Tan nocivos como el fuego y otros desastres naturales pueden resultar para el conocimiento de los textos antiguos los cambios de denominación de los manuscritos. La confusión que produce un nuevo nombre o signatura en un testimonio puede obstaculizar, o incluso impedir, el avance de la investigación, por lo que a filólogos e historiadores se nos impone, como primer paso para el estudio de una tradición manuscrita, la aclaración de las concordancias entre las denominaciones de cada pieza, mutantes a lo largo del tiempo. Descifrar esos códigos puede ser una tarea más o menos exigente en función de la edad de los manuscritos: cuanto más antiguo es un testimonio, mayor cantidad de mudanzas ha podido sufrir de una biblioteca a otra, y más cambios posibles de signaturas. Si además tratamos con tradiciones complejas, compuestas de abundantes testimonios, la dificultad se multiplica.

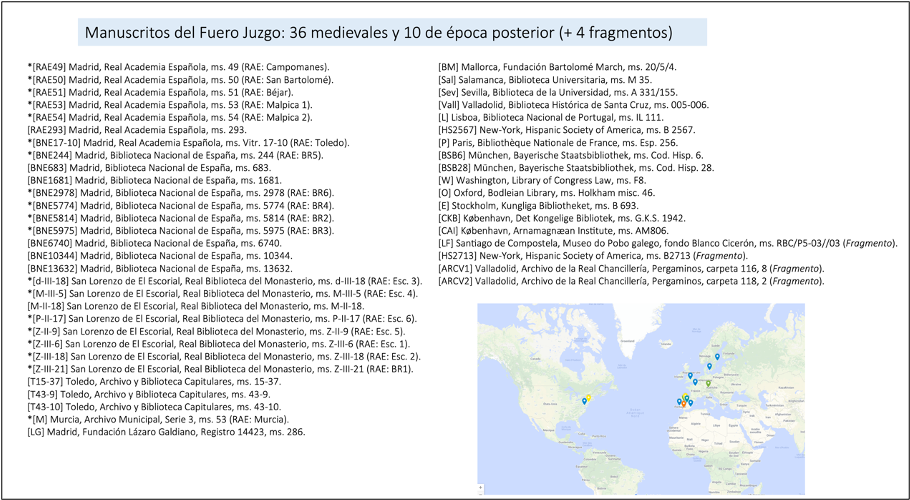

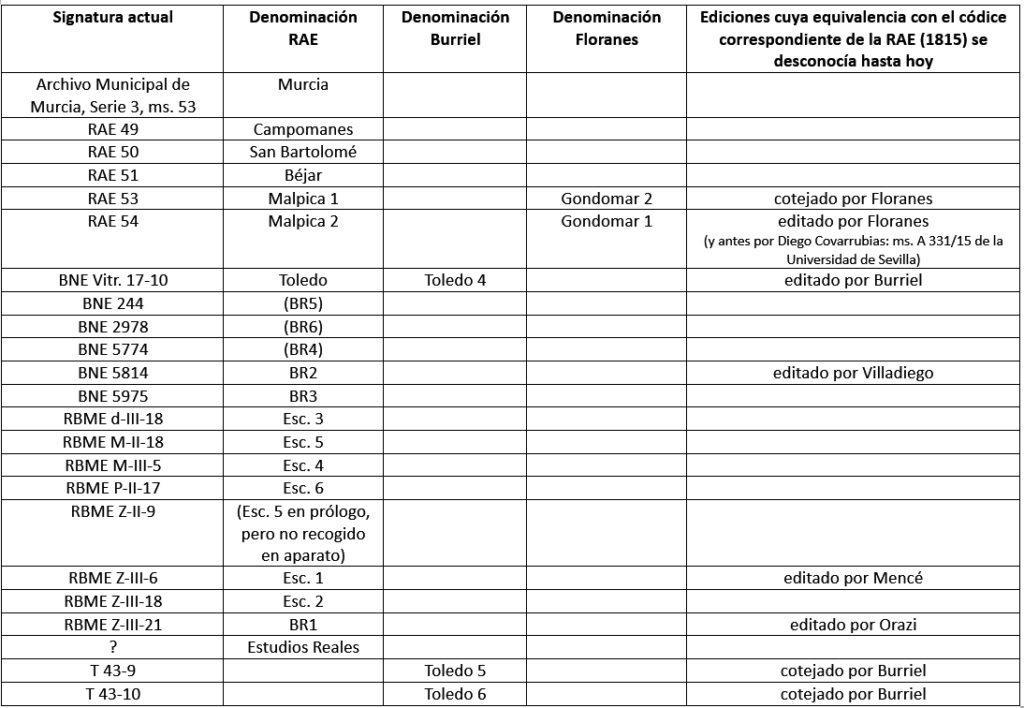

El caso de la tradición manuscrita del Fuero Juzgo reúne todas las características que lo hacen complejo en cuanto a las denominaciones de los testimonios: está constituida por un número elevado de testimonios (50), de los cuales 36 (más 3 fragmentos) son medievales, que han cambiado de poseedores y que se han editado y estudiado haciendo uso de designaciones que ya no corresponden a las de hoy. En consecuencia, muchas preguntas importantes han estado en el aire durante décadas, incluso durante siglos, sobre la tradición manuscrita y las ediciones existentes del Fuero Juzgo: ¿qué manuscrito editó Villadiego en 1600? ¿A qué manuscritos corresponden exactamente las denominaciones que utilizó la RAE en su edición de 1815? ¿Están en el aparato de la edición académica de 1815 los manuscritos que editaron Mencé (1996) u Orazi (1997)? Por muy sorprendente que pueda parecer, nadie hasta la fecha ha intentado establecer una lista completa de correspondencias entre las denominaciones antiguas y las signaturas modernas de los testimonios del Fuero juzgo, como tampoco se ha identificado el manuscrito editado por Villadiego en 1600, y ni siquiera en las ediciones de Mencé y de Orazi se llega a indicar a qué denominaciones académicas (RAE 1815) correspondían los manuscritos escurialenses editados por ambas autoras (Z-III-21 y Z-III-6 respectivamente).

Hasta el momento de publicarse esta entrada, en PhiloBiblon solo se presentaban tres concordancias entre denominaciones antiguas y signaturas modernas, extraídas del catálogo de Zarco Cuevas (1924, 1926, 1929). A estas referencias se limitaba casi el estado de la cuestión, al que debemos añadir otras tres informaciones. En el caso de los otros dos códices estudiados por Orazi (escurialenses P-II-17 y M-II-18), esta autora sí consignó la correspondencia con la denominación académica (Orazi 1997: 40 y 41). A su vez, en su estudio sobre Dialectalismos leoneses de un códice del Fuero Juzgo, García Blanco (1927: 7) identificó el manuscrito que estudió –BNE 5814– con el número 16 de los citados en la edición de la RAE 1815, es decir, con Biblioteca Real 2. Por lo tanto, antes de nuestras investigaciones podríamos contabilizar en total seis concordancias publicadas, de las cuales una, como veremos más adelante, es incorrecta.

El caso del Fuero Juzgo sale bastante mal parado en comparación con otra tradición manuscrita muy próxima: la de las Siete Partidas, que cuenta asimismo con un juego de denominaciones académicas, el empleado en la edición de la RAH de 1807, muy necesitado de correspondencias con las signaturas actuales. Para las Partidas, García y García (1985: 255-257 apud Fradejas Rueda 2021: 23) compuso hace ya cuatro décadas una tabla de correspondencias entre las designaciones de la RAH y las signaturas actuales (véase la tabla adaptada en Fradejas Rueda 2021: 23).

En vista del vacío de conocimiento, y al hilo de nuestras investigaciones sobre el Fuero Juzgo, nos hemos dedicado en los últimos años a identificar los manuscritos que se esconden tras denominaciones distintas y también hemos localizado, mediante una serie de cotejos textuales, el manuscrito que editó Villadiego en 1600. Hemos dado cuenta del juego completo de concordancias en dos conferencias (Castillo Lluch/Mabille 2022 y Castillo Lluch 2023), cuyas versiones escritas se hallan en prensa en este momento (Castillo Lluch/Mabille y Castillo Lluch/García López). En ambas publicaciones se hace mención a la aportación común de Castillo Lluch y Camino Martínez a esa lista de correspondencias mediante intercambios al respecto producidos entre 2021 y 2023.

En este post presentamos los resultados de nuestra investigación, con los que nos complace contribuir a la mejora de los registros de PhiloBiblon. Empezaremos analizando las tres referencias que debemos a Zarco, ofreceremos después el listado de correspondencias de denominaciones antiguas y signaturas modernas que hemos conseguido establecer y, para terminar, nos referiremos a la edición de Villadiego (1600), preguntándonos por el manuscrito que copió.

Zarco Cuevas (1924, 1926, 1929) cataloga el conjunto de manuscritos del Fuero Juzgo custodiados en la Real Biblioteca de El Escorial, y para todo ese conjunto (v. p. 116 del vol. 1 de su catálogo, donde, en la ficha dedicada a d-III-18, menciona la existencia de M-II-18, M-III-5, P-II-17, Z-II-9, Z-III-6, Z-III-18 y Z-III-21), consigue ofrecer tres correspondencias con las denominaciones de la edición académica:

- d-III-18 = ‟Escurialense 3º” en la edición de la RAE (Zarco Cuevas 1924: I, 116).

- M-II-18 = ‟Escurialense 3º” en la edición de la Academia (Zarco Cuevas 1926: II, 284).

- Z-III-18 = ‟Escurialense 2º” en la edición de la ‟Academia de la Historia” (sic, léase RAE) (Zarco Cuevas 1929: III, 149).

La concordancia de ‟Escurialense 3º” con dos manuscritos es, evidentemente, errónea, pues a cada uno de esos dos debería corresponderle una denominación distinta en la edición académica. Zarco se equivocó con M-II-18, que en realidad es el designado como ‟Escorial 5º” en el aparato de variantes de la RAE, si bien la descripción inicial que los académicos ofrecen de ese manuscrito escurialense 5º (RAE 1815: prólogo, 5-6) corresponde a Z-II-9. Se suman aquí, por tanto, dos fallos: uno de la RAE al describir Z-II-9 en el prólogo a su edición dándole por nombre Escorial 5º, pero después no incluyéndolo en su aparato, y en su lugar introduciendo las variantes de M-II-18; y el de Zarco Cuevas, que asimila M-II-18 a Escurialense 3º.

Otro detalle que debe tenerse en cuenta es que el número de testimonios medievales que tuvo la Academia para su edición de 1815 fue de 21; pero, en la práctica, se ofrece el texto de Murcia en el cuerpo de la página y en el aparato crítico recoge las variantes de 16 códices (omite las de BR4, BR5, BR6 y las de Z-II-9, que había descrito en el prólogo por error como Esc 5, pues, como se acaba de ver, en el aparato Esc 5 es M-II-18).

Ofrecemos a continuación el listado de los manuscritos del Fuero Juzgo que manejaron los académicos para su edición de 1815, y también la que usó algunas décadas más atrás Andrés Marcos Burriel (1755), primer editor del manuscrito de Murcia y precursor de la edición académica, por haber elegido ese códice como manuscrito óptimo y porque incluye variantes de otros dos manuscritos romances que desconoció la Academia (actuales T 43-9 y T 43-10). Incorporamos también la información relativa a la edición de Rafael Floranes (1780), basada en el códice RAE 54, que cotejó con RAE 53, con otro de su propiedad que no tuvo la RAE para su edición (RAE 293), y también con el texto editado por Villadiego (Camino Martínez 2021 y 2022). Entre paréntesis se indican los manuscritos que la Academia tuvo a la vista, pero que no incluyó en su aparato crítico. La última columna de la tabla contiene la identificación a partir de las signaturas actuales de los manuscritos que fueron editados sin indicar, por desconocimiento, a qué denominación de la RAE correspondían (obviamente esto no hace para las ediciones de Villadiego, Burriel o Floranes, anteriores a la edición académica).

Por último, expondremos cuál era el estado de la cuestión con respecto al manuscrito editado por Villadiego en 1600 y el procedimiento que hemos seguido para identificarlo. En las ‟Advertencias necesarias a la claridad desta obra” que preceden a su edición, Villadiego (1600: 7) se limitaba a informar de que el códice del que copiaba procedía de ‟vna libreria muy antigua, escrito de mano, y en pergamino” y que Antonio de Covarrubias lo estudió y comentó entre 1596 y 1598. Entre los preliminares de ese impreso de Villadiego, se encuentra un ‟Testimonio de la libreria de la santa Iglesia de Toledo” en el que se confirma que concordaba el texto del original de imprenta de Villadiego con el ‟Fuero Iuzgo que tiene esta santa Iglesia mayor en su libreria”. Siglo y medio más tarde, Burriel (1754: 270-271) también indicaba que esa edición se basaba en un ‟tomo manuscrito de la Iglesia de Toledo”. Ahora bien, en un estudio reciente (cf. Castillo Lluch y Mabille 2021: 80, n. 11), tras haber examinado algunos pasajes del texto de la edición de 1600, hemos podido probar que el testimonio que copia Alonso Villadiego no es el de ninguno de los toledanos que manejó Burriel (T4, T5, T6) ni tampoco es T 15-37. Dado que hoy no se conserva ningún manuscrito antiguo en Toledo que no sean T5 (T 43-9), T6 (T 43-10) y T 15-37, y que T4 (hoy BNE Vitr. 17-10) tampoco es el modelo, ¿se trataría de un manuscrito que se conservaba en Toledo antes del siglo xvii y después se desplazó a otro lugar? Ignoramos muchos detalles de la conservación de los distintos manuscritos en diversos repositorios, pero en el caso de algunos, como, por ejemplo, RAE 54, hemos inferido, a partir de unas anotaciones en el recto del primer folio que había quedado en blanco, que ‟en el último cuarto del siglo xiv debía encontrarse en Toledo” (Camino Martínez 2018: 74).

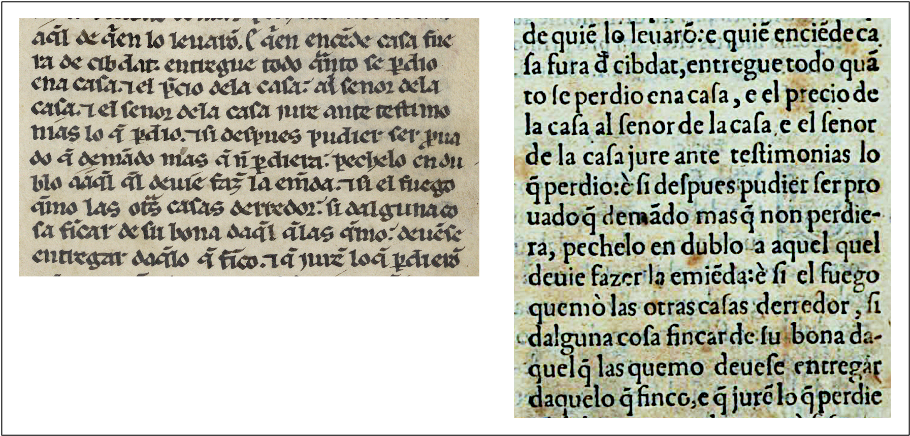

Mediante un cotejo de un fragmento de 8.2.1 de la edición de Villadiego con, además de los cuatro toledanos ya mencionados, 24 manuscritos antiguos a nuestra disposición (escurialenses Z.III.21, P.II.17, M.II.18, M.III.5, d.III.18, Z.III.6, Z.III.18, académicos 49, 50, 51, 53, 54, 293, el BNF 256, el Hisp. 6 de la Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, el IL 111 de Lisboa, el de Estocolmo, el de la Biblioteca Real de Copenhague, el de Oxford, los de las fundaciones Lázaro Galdiano y Bartolomé March y los de la BNE 5774, 5814 y 244), hemos logrado identificar ese testimonio occidental que edita Villadiego en 1600 como BNE 5814 (véanse imágenes 3 y 4).

Imagen 5: Folios 171v y 172r del ms. BNE 5814 con la rúbrica en el margen inferior de Ambrosio Mexia, escribano público, que comprobó la concordancia entre el original de imprenta de Villadiego y el manuscrito que en aquel momento se encontraba en la librería de la catedral de Toledo.

La identificación de este manuscrito permite ahora a los investigadores al menos dos cosas: controlar la calidad de la edición de Villadiego, tan a menudo criticada por editores posteriores, y valorar la decisión del siguiente editor del Fuero Juzgo en el tiempo: Andrés Marcos Burriel (1755), que prefirió editar el manuscrito de Murcia. La lista completa de concordancias entre denominaciones antiguas y signaturas actuales de los testimonios que nos han transmitido el Fuero Juzgo aclarará a toda persona interesada por este texto a qué manuscritos exactamente han hecho referencia desde hace décadas estudiosos que nos han dejado lecciones importantes sobre la ley visigótica en romance utilizando la nomenclatura de la edición de la RAE (pensamos en Yolanda García López 1996 y en José Manuel Pérez Prendes 1957) o la de Floranes (Mª Luz Alonso Martín 1983 y 1985). La incorporación a PhiloBiblon de nuestras concordancias garantiza que esta información esté a partir de ahora fácilmente accesible para toda la comunidad científica.

Obras citadas

– Alonso Martín, Mª Luz (1983), ‟Nuevos datos sobre el Fuero o Libro castellano: Notas para su estudio”, Anuario de Historia del Derecho Español LIII, 423-445.

– Alonso Martín, Mª Luz (1985), ‟Observaciones sobre el Fuero de los Castellanos y las leyes de Nuño González”, Anuario de Historia del Derecho Español LV, 773-781.

– Burriel, Andrés Marcos (1755), Fuero Juzgo ò Codigo de las leyes que los reyes godos promulgaron en España. Traducido del original latino en lenguage castellano antiguo por mandado del Santo Rey D.n Fernando III.º, copiado de un exemplar autentico del Archivo de la Ciudad de Murcia, y de otros tres mss. antiquisimos de la libreria de la S.ta Iglesia de Toledo, ajustado al original latino, ilustrado, y corregido por el P.e Andrès Marcos Burriel de la Comp. de Jesus, Manuscrito BNE 683.

– Camino Martínez, Carmen del (2018), ‟Notarios, escritura y libros jurídicos. Algunas consideraciones”, en Miguel Calleja-Puerta y María Luisa Domínguez-Guerrero (eds.), Escritura, notariado y espacio urbano en la Corona de Castilla y Portugal (siglos xii-xvii), Gijón, Trea, 63-79.

– Camino Martínez, Carmen del (2021), ‟En torno al Libro de Nuño González y algunos manuscritos toledanos del Fuero Juzgo”, en Juan Carlos Galende Díaz (dir.) y Nicolás Ávila Seoane (coord.), Libro homenaje al profesor don Ángel Riesco Terrero, Madrid, ANABAD Federación y Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 65-74.

– Camino Martínez, Carmen del (2022), ‟El erudito, el calígrafo y dos ejemplares dieciochescos del Fuero Juzgo”, comunicación presentada en el coloquio Los manuscritos del Fuero Juzgo: abordaje interdisciplinar, Université de Lausanne, 11-12 de noviembre de 2022.

– Castillo Lluch, Mónica (2022), ‟La tradición manuscrita del Fuero Juzgo: una visión de conjunto”, comunicación presentada con Charles Mabille en el XII Congreso Internacional de Historia de la Lengua Española, Universidad de León, 16 de mayo de 2022.

– Castillo Lluch, Mónica (2023), ‟The Visigothic Code and the Fuero Juzgo: The Transmission and Translation of Law from Latin to Romance”, conferencia pronunciada en Yale University, 28 de abril de 2023.

– Castillo Lluch, Mónica y Mabille, Charles (2021), ‟El Fuero Juzgo en el ms. BNE 683 (1755) de Andrés Marcos Burriel”, Scriptum digital 10, 75-107.

– Castillo Lluch, Mónica y Mabille, Charles (en prensa), ‟Hacia un stemma codicum del Fuero Juzgo desde el Humanismo hasta hoy”, en Actas del XII Congreso Internacional de Historia de la Lengua Española.

– Castillo Lluch, Mónica y García López, Yolanda (en prensa), ‟The Visigothic Code and the Fuero Juzgo: The Transmission and Translation of Law from Latin to Romance”, en Noel Lenski y Damián Fernández (eds.), Lex Visigothorum, Cambridge University Press.

– Floranes, Rafael (1780) Fuero Juzgo. Manuscrito cotejado con varios exemplares, Manuscrito BNE 10344.

– Fradejas Rueda, José Manuel (2021), ‟Los testimonios castellanos de las Siete Partidas”, en José Manuel Fradejas Rueda, Enrique Jerez Cabrero, y Ricardo Pichel (eds.), Las Siete Partidas del Rey Sabio: una aproximación desde la filología digital y material, Madrid/Frankfurt, Iberoamericana/Vervuert, 21-35.

– García Blanco, Manuel (1927), Dialectalismos leoneses de un Códice del Fuero Juzgo, Salamanca, Imp. Silvestre Ferreira.

– García López, Yolanda (1996), Estudios críticos y literarios de la ‟Lex Wisigothorum”, Alcalá de Henares, Servicio de publicaciones de la Universidad de Alcalá.

– Mencé, Corinne (1996), Fuero juzgo (Manuscrit Z.iii.6 de la Bibliothèque de San Lorenzo de El Escorial), 3 vols., Lille, ANRT.

– Orazi, Verónica (1997), El dialecto leonés antiguo (edición, estudio lingüístico y glosario del Fuero Juzgo según el ms. Escurialense Z.iii.21), Madrid, Universidad Europea-CEES Ediciones.

– Pérez-Prendes Muñoz de Arraco, José Manuel (1957), La versión romanceada del Liber Iudiciorum. Algunos datos sobre sus variantes y peculiaridades, Tesis doctoral inédita dirigida por Manuel Torres López, Madrid, Universidad Complutense.

– Real Academia Española (ed.) (2015 [1815]), Fuero Juzgo en latín y castellano, cotejado con los más antiguos y preciosos códices, con estudio preliminar de Santos M. Coronas González, Madrid, Agencia Oficial Boletín Oficial del Estado.

– Villadiego Vascuñana y Montoya, Alonso (1600), Forus antiquus gothorum regnum Hispaniae, olim Liber Iudicum hodie Fuero Iuzgo nuncupatus, Madrid, Pedro Madrigal.

– Zarco Cuevas, Julián (1924, 1926, 1929, 3 vols.), Catálogo de los manuscritos castellanos de la Real Biblioteca de El Escorial dedicado a S.M. el rey don Alfonso XIII, Madrid, Imprenta Helénica (vols 1 y 2) y San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Imprenta del Real Monasterio de El Escorial (vol. 3).

Arab-American Heritage Month 2024

Hey there, bookworms! Ready to celebrate Arab American Heritage Month with a literary twist? Join us as we dive into the captivating world of Arab-American authors and characters and their vibrant stories, both fiction and nonfiction. Explore more at UCB Overdrive today!

Kaveh Akbar

Etaf Rum

Aisha Abdel Gawad

Sarafina El-Badry Nance

Hanan al-Shaykh

Nazanine Hozar

Women’s History Month 2024

Empowerment, inspiration, and a dash of magic: Celebrating Women’s History Month with a collection that bridges worlds, both real and imagined, penned by fierce women who redefine history, one page at a time! Check out UCB Overdrive for more great finds.

Mattie Kahn

Vanessa Chan

Safiyah Sinclair

Kristin Hannah

Parini Shroff

Margaret Verble

Jasmine Brown

Jenni Nuttall

Sandra Guzman

Graphic Narrative Art by Emily Ehlen from OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

Below are ten graphic narrative illustrations created by artist Emily Ehlen that she drew from stories and themes in the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, or JAIN project, recorded by the Oral History Center, or OHC.

The OHC’s JAIN project documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three Japanese American survivors and descendants of the World War II incarceration to investigate the impacts of healing and trauma, how this informs collective memory, and how these narratives change across generations. Initial interviews in the JAIN project focused on the Manzanar and Topaz prison camps in California and Utah, respectively. The JAIN project began at the OHC in 2021 with funding from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. The grant provided for 100 hours of new oral history interviews, as well as funding for a new season of The Berkeley Remix podcast and for Emily Ehlen’s unique artwork below, all based on the JAIN project oral histories.

We encourage you to use and share Emily Ehlen’s artwork, along with the JAIN project oral history interviews, especially in classrooms when teaching the history and legacy of the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. When using these images, please credit Emily Ehlen as the artist (for example, Fig. 1, Ehlen, Emily, WAVE, digital art, 2023, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley), and see the OHC website for more on permissions when using our oral histories. To save a digital copy of any illustration below for fair use, right click on the image and select “Save Image As…” The text description that accompanies each illustration below aims to provide accessibility for the visually impaired in lieu of Alt-Text limitations, which does not easily accommodate graphic narrative images. In a separate blog post, you can learn more about the artist Emily Ehlen and her processes while creating these dynamic illustrations drawn from the memories and reflections of JAIN oral history narrators.

Artist’s statement

Emily Ehlen’s illustrations for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project convey compelling narratives and imagery, with impactful shapes and color, by crafting traditionally and translating images into digital pieces. She uses text and imagery to balance the composition and support storytelling elements. Her work encompasses themes of identity and belonging, intergenerational connections, and healing. The collection navigates the impact and experiences of Japanese American incarceration during World War II and its effects on future generations.

WAVE by Emily Ehlen

This image titled WAVE consists of two panels. The top panel depicts text that relates to the number of generations of Japanese descents surrounding a family portrait using barbed wires as arrows. The text is in romanized Japanese and kanji. It reads: “Issei,” meaning first generation; “Nisei,” meaning second generation; “Sansei,” meaning third generation; “Yonsei,” meaning fourth generation; and “Gosei,” meaning fifth generation. The bottom panel depicts a large wave and guard tower behind barbed wire with text above that reads, “Your generation is just one part of the wave, and you do your best to build what you can for the next generation in your family.”

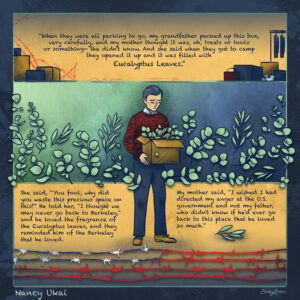

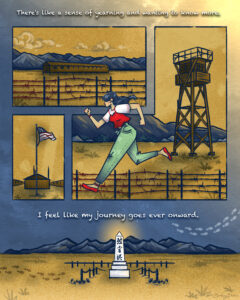

MANZANAR by Emily Ehlen

This image titled MANZANAR consists of four different panels. Each panel depicts a part of an incarceration camp and features barbed wire, the American flag, and the buildings in the camp. Above the top panel there is text that reads, “There’s like a sense of yearning and wanting to know more.” In the middle right panel, a woman in a red top layered over a white T-shirt and green pants runs towards the left of the image. The bottom panel depicts the cemetery monument at Manzanar National Historic Site, with Japanese kanji written on top, which reads, “I REI TO,” or “soul consoling tower.” Below the bottom panel there is text that reads, “I feel like my journey goes ever onward.”

STORIES by Emily Ehlen

This image titled STORIES consists of four panels. The top panel depicts a growing boy talking to his mother. An incarceration camp appears behind the mother. Above this top panel, the text reads, “My mom would not speak of things in camp. Maybe she didn’t want to or couldn’t at the time. It wasn’t ’til I was older did she begin telling me stories of camp.” Under this top panel, the text reads, “I got to know more about my mom, about a part of her life when I wasn’t there.” Two middle panels follow, depicting a green puzzle piece and crying eyes behind barbed wire. The text between these panels reads, “The missing piece she kept. The sadness she concealed.” In the bottom panel, tears from the eyes above fall into a plant on the ground that is growing. The text on this panel reads, “Talking about it didn’t make the pain disappear, but letting her experiences come to light brought a place for healing.”

TEACHER by Emily Ehlen

This image titled TEACHER consists of four panels. The top left panel shows a male teacher next to a chalkboard. The text on the chalkboard reads, “In middle school, we were learning about the Holocaust, and our teacher was telling the whole class like, ‘Well, Jewish people were put in camps…'” The top right panel depicts a raised hand with text that reads, “And I was like, ‘Wait, my grandmother was put in a camp.’ So I raised my hand.” The middle panel depicts a girl sitting at a desk, a male teacher standing, and a large crack between them. On the left of the panel, the girl says, “My grandparents were put in a camp, but they were put in a camp by America.” The text in the large crack reads, “And there was this awkward silence.” The teacher responds, “Well, we didn’t kill people.” The word “kill” has a red strikethrough on it. The bottom panel depicts the girl at the desk alone in the dark. The text reads, “I remember that as the first time I felt like my experience was disparaged or put down, but I was too young to really understand that.” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Miko Charbonneau’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

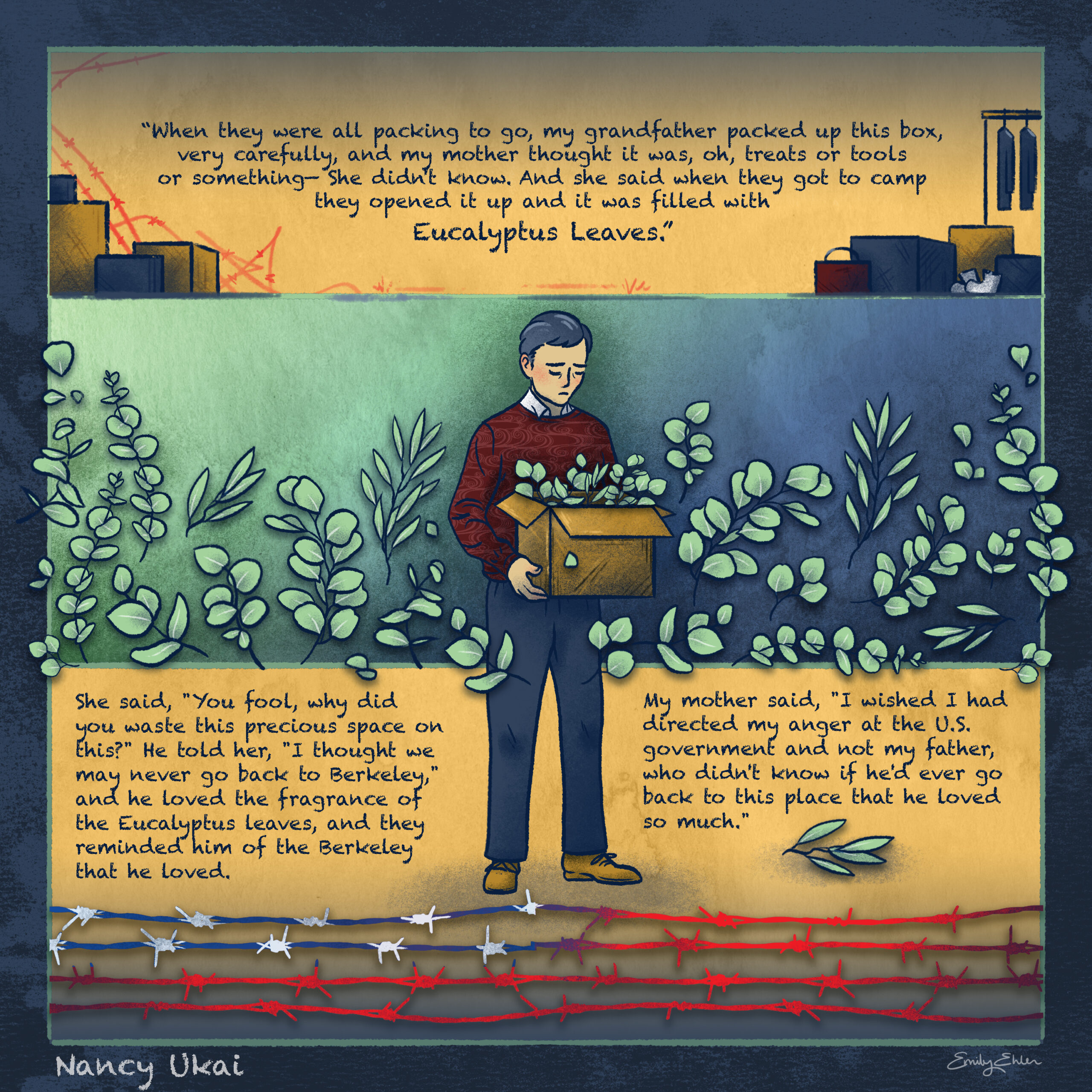

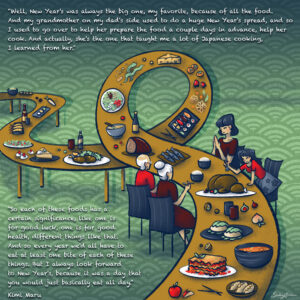

EUCALYPTUS by Emily Ehlen

This image titled EUCALYPTUS consists of three panels. The top panel depicts suitcases and boxes of various sizes, and includes text which reads, “When they were all packing to go, my grandfather packed up this box, very carefully, and my mother thought it was, oh, treats or tools, or something—she didn’t know. And she said when they got to camp and opened it up and it was filled with Eucalyptus Leaves.” The words “eucalyptus leaves” are larger than the other words. In the center, the grandfather stands in front of all of the panels with a box of eucalyptus leaves. He is looking down with a sad expression. The bottom panel depicts some eucalyptus leaves as well as barbed wire that mimics the red, white, and blue of an American flag. This panel includes text which reads, “She said, ‘You fool, why did you waste this precious space on this?’ He told her, ‘I thought we may never go back to Berkeley,’ and he loved the fragrance of the Eucalyptus leaves, and they reminded him of the Berkeley he loved. My mother said, ‘I wished I had directed my anger at the U.S. government and not my father, who didn’t know if he’d ever go back to this place that he loved so much.'” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Nancy Ukai’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

SPLASH by Emily Ehlen

This image titled SPLASH consists of two panels on the top and two on the bottom. The top left panel depicts a younger woman and an older woman in a boat. Text above the top two panels reads, “The U.S. Government told my mother, ‘It is advisable that you move as far away from California as you can. Stay away from other Japanese. Try to become even more American than you think you are, than you already are.'” The top right panel depicts the two women holding hands and standing in the boat. The text below these panels reads,”‘Just quietly go about your business even though this horribly unconstitutional thing has just happened to you and you’ve suffered all this trauma. But try to be American. Try to fit in.'” The bottom left panel depicts a close-up of the women holding hands above the boat and a ripple in the water. Beneath the hands, the text reads, “We were told, ‘Don’t rock the boat, do not make waves.” Beneath the boat, the text reads, “Nonsense. Let’s go make a Big Splash!” The bottom right panel depicts the two women holding hands and jumping into a sea of waves. Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Jean Hibino’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

TOPAZ by Emily Ehlen

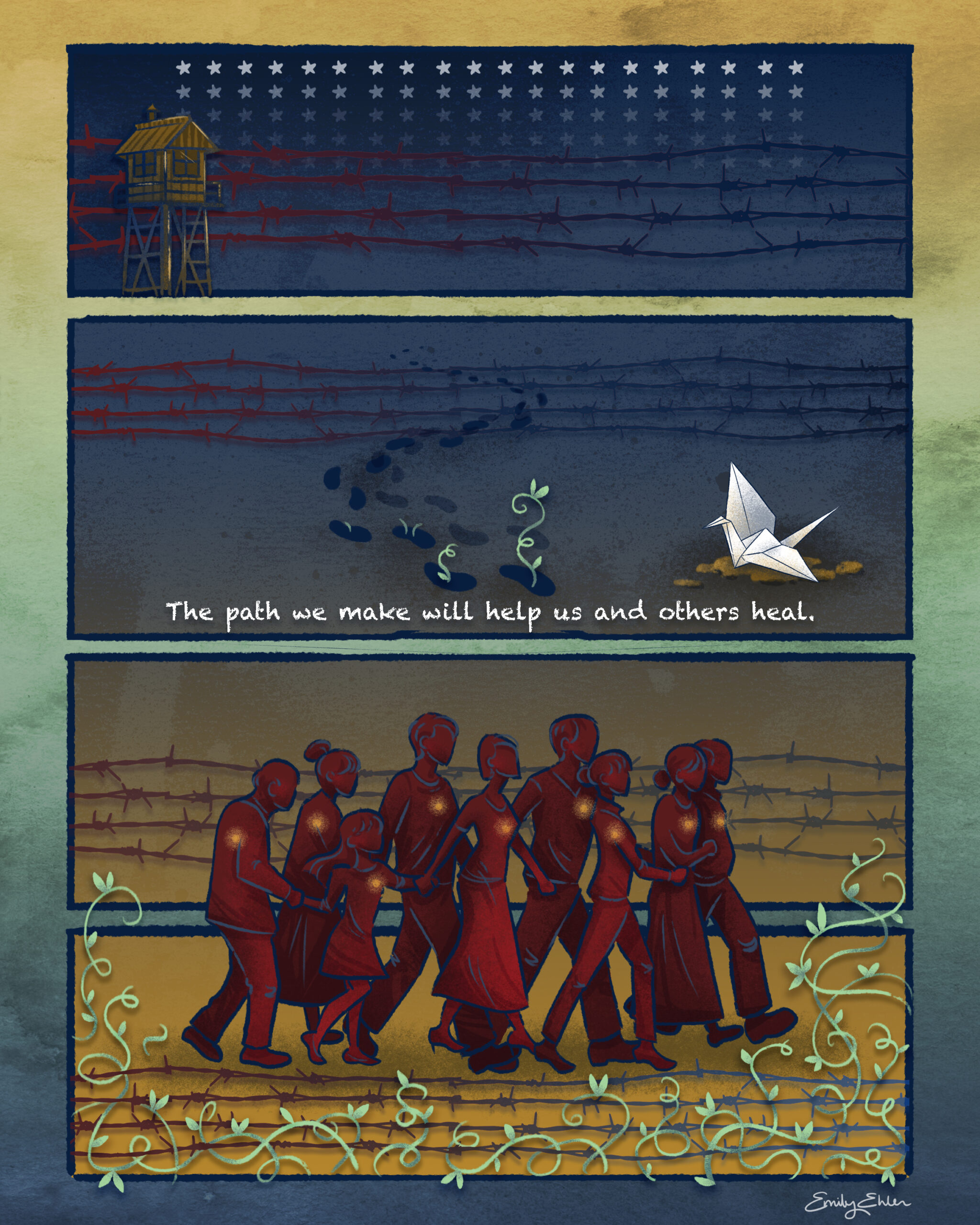

This image titled TOPAZ consists of four panels. The top panel depicts white stars behind barbed wire in red and blue that mimics the American flag, as well as a guard tower. The next panel depicts footsteps with plants sprouting from the final four steps. To the right of the footsteps, a white paper crane rests on soil. Red and blue barbed wire appears in the background. Text at the bottom of this panel reads, “The path we make will help us and others heal.” The bottom two panels depict barbed wire at the top and bottom, which frame a group of people all holding hands walking to the right. The group of people, which includes a range of ages, spans both panels. The individuals have glowing lights over their hearts. Plants sprout from the bottom of this panel.

SILENCES by Emily Ehlen

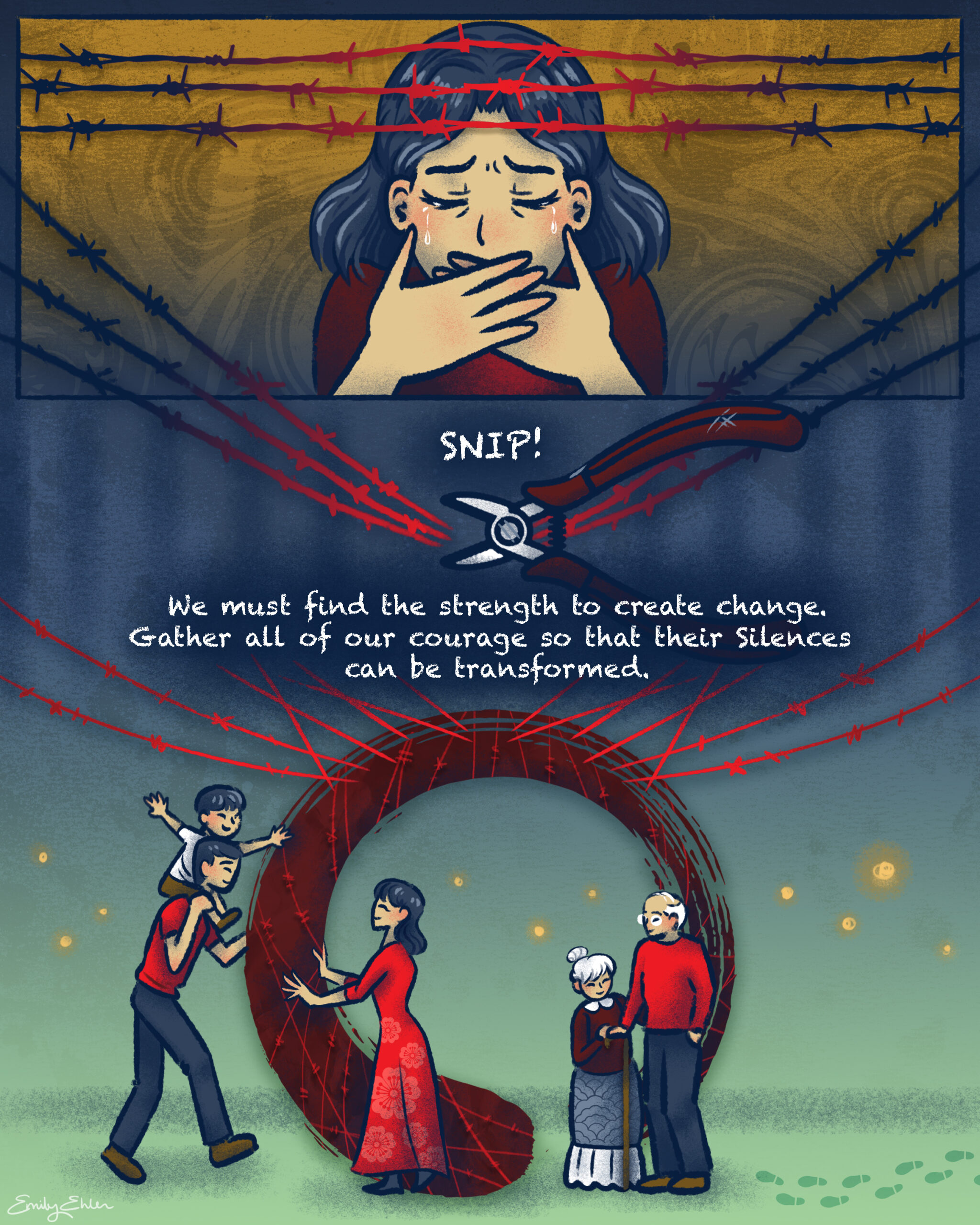

This image titled SILENCES consists of two panels. In the top panel, a woman cries while framed by red barbed wire. The bottom panel depicts wire cutters snipping the red barbed wire. Text reads, “SNIP!” Beneath the barbed wire is text that reads, “We must find the strength to create change. Gather all of our courage so that their silences can be transformed.” Beneath this text is a scene depicting a man with a child on his shoulders moving toward a woman with open arms. To the right of them are an elderly woman and man. Behind the group of people, there is a large, red circular ensō formed from the barbed wire. Glowing lights also appear in the background.

TREE by Emily Ehlen

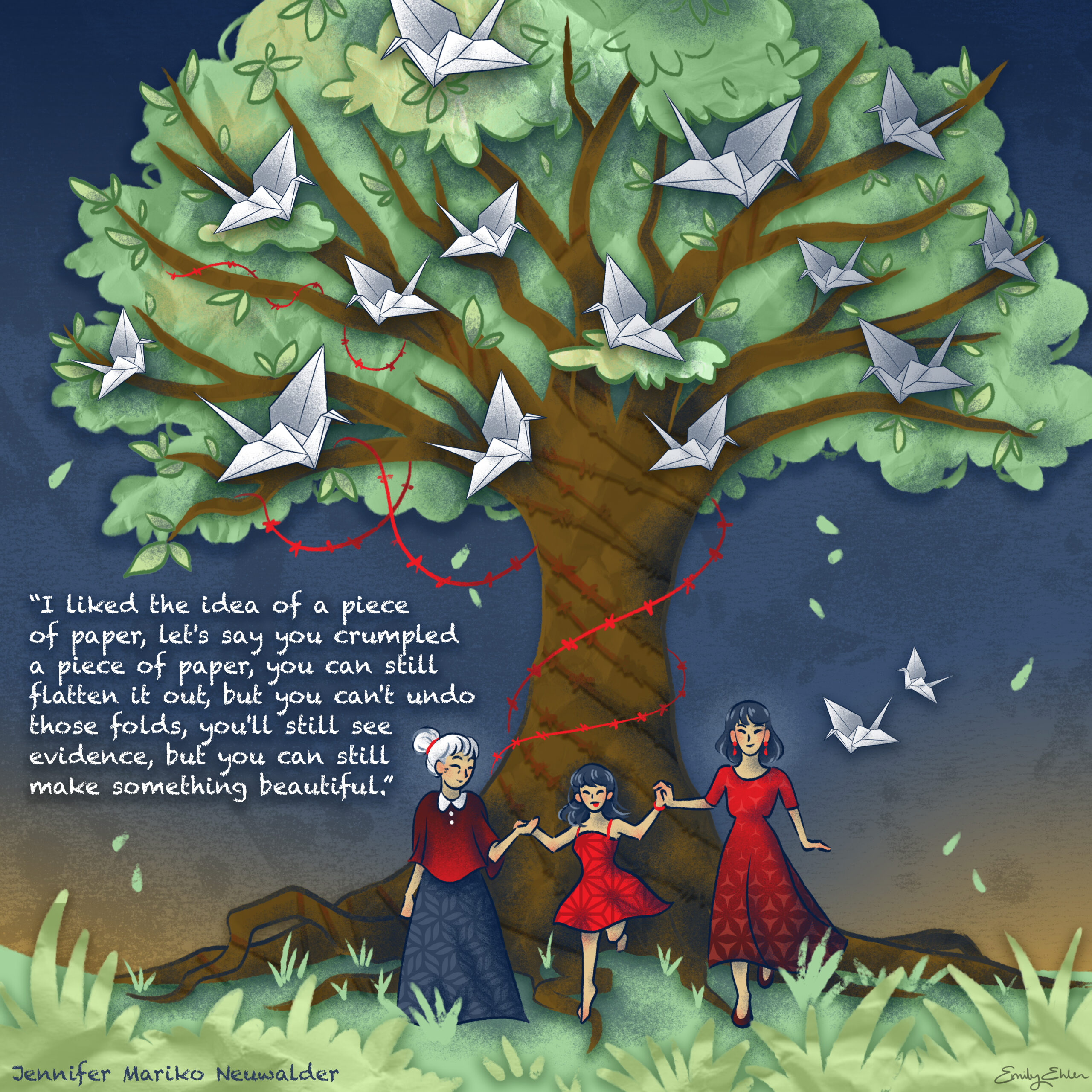

This image titled TREE consists of one panel, depicting three women of different generations holding hands in front of a large tree wrapped in red barbed wire and filled with white paper cranes. This image includes text which reads, “‘I liked the idea of a piece of paper, let’s say you crumpled a piece of paper, you can still flatten it out, but you can’t undo those folds, you’ll still see evidence, but you can still make something beautiful.” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

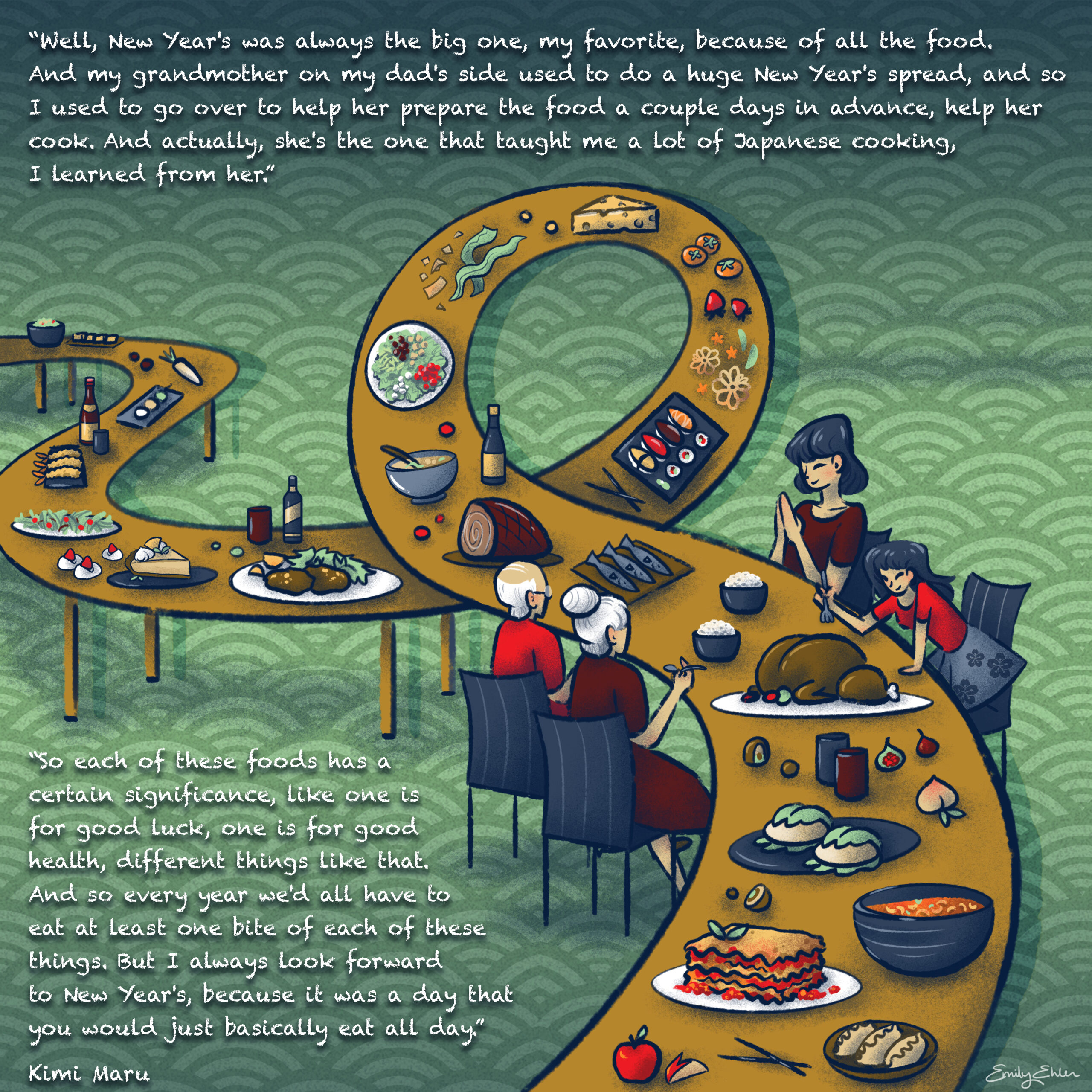

FEAST by Emily Ehlen

This image titled FEAST consists of one panel that depicts a long table that stretches from the left side to the bottom right which loops before reaching four people of different generations eating. The food on the table includes a variety of foods like sushi, lasagna, salad, turkey, and dumplings. Text at the top of the image reads, “‘Well, New Year’s was always the big one, my favorite, because of all the food. And my grandmother on my dad’s side used to do a huge New Year’s spread, and so I used to go over to help her prepare the food a couple days in advance, help her cook. And actually, she’s the one that taught me a lot of Japanese cooking, I learned from her.'” Text on the bottom left of the image reads,, “‘So each of these foods has a certain significance, like one is for good luck, one is for good health, different things like that. And so every year we’d all have to eat at least one bite of each of these things. But I always look forward to New Year’s, because it was a day that you would just basically eat all day.'” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Kimi Maru’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

Explore the oral history interviews in the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, listen to The Berkeley Remix podcast season “’From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” and discover related resources on the Oral History Center website.

Acknowledgments for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

This material received federal financial assistance for the preservation and interpretation of U.S. confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability or age in its federally funded assisted projects. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to:

Office of Equal Opportunity

National Park Service

1201 Eye Street, NW (2740)

Washington, DC 20005

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Q&A with Artist Emily Ehlen on Illustrating the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

For the first time, the Oral History Center, or OHC, partnered with an artist named Emily Ehlen, who created ten graphic narrative illustrations based upon stories and themes recorded in the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, or JAIN project. The JAIN project documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The OHC’s JAIN project documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three Japanese American survivors and descendants of the World War II incarceration to investigate the impacts of healing and trauma, how this informs collective memory, and how these narratives change across generations. Initial interviews in the JAIN project focused on the Manzanar and Topaz prison camps in California and Utah, respectively. The JAIN project began at the OHC in 2021 with funding from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. The grant provided for 100 hours of new oral history interviews, as well as funding for a new season of The Berkeley Remix podcast and Emily Ehlen’s unique artwork, all based on the JAIN project oral histories.

Below is an interview with Emily Ehlen about her processes in creating such dynamic illustrations drawn from the memories and reflections of JAIN oral history narrators. You can see and save copies of larger images of Emily’s artwork for the JAIN project in a separate blog post.

Artist Bio:

Emily Ehlen is best known for her colorful and whimsical illustrations using mixed media. Watercolor, ink, spray paint, and gouache are the primary mediums she uses for her traditional works, and she also integrates them in her digital pieces. She loves being positive and expressing her interests while using her surroundings as inspiration. To invoke curiosity and imagination, her drawings reflect an open view of the subject and are framed with pieces of expression and reality. Change and adaptability are a constant as she goes through various experimentations and approaches to her art.

Q&A with artist Emily Ehlen:

Q: What was your process for creating the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives artwork?

Emily Ehlen: My process started with selecting powerful imagery and phrases in relation to connecting themes found throughout the oral history transcripts. I composed thumbnails with the intent to represent the information clearly and use symbolism to convey the narrative. I wanted to use as much text from the source as I could, but I wanted to avoid it being too word heavy. It was a balancing act of editing the text and imagery to support each other in the composition and narrative. After developing and consolidating the initial drafts I moved on to tighter linework and color concepts. Once the colors were established, I inlaid patterns and handmade textures to add contrast between objects, panels, and the background. The handmade textures were made with ink washes and spray paint. The final step was applying shading and details to enhance the focus of each element while also keeping the flow throughout the entire composition.

Q: How was your work on this project similar or different to your prior art projects?

Emily Ehlen: This Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives art project was similar to the comic series Drawn to Art: Tales of Inspiring Women Artists that I worked on in 2021 for the Smithsonian American Art Museum. For that Smithsonian project, I drew a three page comic called “Weaver’s Weaver,” featuring Kay Sekimachi, a Japanese American artist. My process for both projects were pretty identical. Although, I think I had a little more freedom with expanding the storytelling elements working on the JAIN project comics. Overall, they were mutually great experiences that I am so grateful to have been a part of.

Q: How did engaging with the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives oral history transcripts shape the stories you chose to tell and some of the imagery you used in your graphic art?

Emily Ehlen: When drafting the concepts of the illustrations, I wanted to use imagery that would convey the message the stories presented. Reading the oral history transcripts, I found lots of interesting details to include, like with the different types of food to include in the FEAST composition. It was inspiring to hear everyone’s unique voice sharing aspects about their and their family’s lives.

Q: How did you choose the various scenes and stories that you eventually depicted? What stories in the transcripts most stood out to you? Why?

Emily Ehlen: I illustrate with the goal to portray a story the audience can connect and respond to. I wanted to choose stories with lots of emotions that I could highlight in each drawing. The piece I got the most emotional while drawing was Nancy Ukai’s grandfather in EUCALYPTUS. I sympathized with the longing and sadness of missing Berkeley that her grandfather felt. I understood the rationality behind using the box for something else, but that emphasized just how important Berkeley was to him. It was heartbreaking to read, so I knew I had to draw it.

Q: What are some of the story themes that you worked to express throughout your art for this project?

Emily Ehlen: The focus was how the Japanese American incarceration during World War II impacted themselves, their families, and how they responded to it. The themes were identity and belonging, intergenerational connections, and healing. I wanted the weight of the words to be carried through to the art accompanied with them.

Q: Can you describe some of the visual themes or repeated imagery that you incorporated throughout the various pieces you created? How and why did you develop these visual themes?

Emily Ehlen: The color palette I used helped create the tone and atmosphere of each piece separately while also keeping the collection cohesive. The red was used with duality: the bright saturated hue represented youth, rebelliousness, and intensity; while the dark maroon represented authority and repressed quietness. The soft green color was used to depict change and positivity that connects to the healing theme. The navy blue signifies unity and freedom, but it is used with a sense of serenity and heaviness. For example, the blue in TEACHER extrudes an overbearing presence in contrast to when it’s used in TREE. The ochre yellow has different meanings for its surroundings, like in TEACHER it signifies uncertainty, and in STORIES it’s used to display hope.

The water pattern, waves, and watercolor texture are used with family elements, and it contrasts the dry gritty spray paint texture that references the environment of Topaz and Manzanar. Waves are symbols of growth, renewal, and transformation. They also represent the unpredictability of life, to which people learn to navigate its ups and downs. The plants and paper cranes also relate to family connections, development, and healing, going through many stages and flourishing together.

For darker imagery, I wanted the red barbed wire to be synonymous with the red stripes we see on the American flag. To show the lack of freedom and injustice that the Japanese Americans faced, those stripes became wire that entrapped and left scars on following generations. The guard towers were a beacon of looming authority and danger at the incarceration camps. They became a mental block for some that were confined in their silences.

Q: While creating the JAIN art, what did you learn that was new to you?

Emily Ehlen: I really enjoyed learning about everyone’s perspectives and experiences with being Japanese American. I am Chinese American, so I empathize with the stories about identity and the sense of belonging. This project lit up my desire to discover more about my culture. My motivation for drawing is to see how my art mirrors my development as a person. I think art is a record of growth and change. Like time, it never stops moving forward.

Q: Can you describe one or two of your favorite pieces that you created for this project? Why does this one stand out for you?

Emily Ehlen: This is like asking the question, “Who’s your favorite child?” It’s super difficult because I love each piece for different reasons. I had the most fun drawing the piece SPLASH, about Jean Hibino and her mother. I think it has the most dynamic composition with how the imagery flows together with the text. I like the sequence of stillness to movement, and how a ripple can start a wave.

Q: What are your hopes for how people engage with your art for this project? Who do you hope sees it? What do you hope people take away from your art for this project?

Emily Ehlen: My hope for how people engage with the comic is to have open conversations about them or topics related to it. It would be nice to see what sticks out to people the most and what connections they make through their perspectives. I hope people are able to feel the sentiments in each piece and learn new aspects of its history. I can’t think of anyone specific I’d want to see it, but I strive to be someone who inspires others by taking creative approaches to new ideas. So, I hope other artists who are interested in drawing and story-telling see it

You can see and save copies of larger images of the graphic art that Emily Ehlen created for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project in a separate blog post. We encourage you to use and share Emily Ehlen’s artwork, along with the JAIN project oral history interviews, especially in classrooms when teaching the history and legacy of the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. When using these images, please credit Emily Ehlen as the artist (for example, Fig. 1, Ehlen, Emily, WAVE, digital art, 2023, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley), and see the OHC website for more on permissions when using our oral histories.

Acknowledgments for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

This material received federal financial assistance for the preservation and interpretation of U.S. confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability or age in its federally funded assisted projects. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to:

Office of Equal Opportunity

National Park Service

1201 Eye Street, NW (2740)

Washington, DC 20005

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

PhiloBiblon en el #DARIAHDay 2023

La Biblioteca Nacional de España se dispone a celebrar hoy el #DARIAHDAY, que debe su nombre a la red DARIAH , formada por investigadores de diferentes países europeos y en la que se proyectan casi todas las actividades de artes y humanidades digitales del Viejo Continente. El acto forma parte del programa Bibliotecas, datos, inteligencia artificial: las nuevas rutas del conocimiento (7-8 de noviembre de 2023), cuyo calendario completo se puede seguir en las redes sociales a través de la ya mencionada citada etiqueta: #DARIAHDAY

⌛️Empieza la cuenta atrás para “Bibliotecas, datos, inteligencia artificial: las nuevas rutas del conocimiento”, las jornadas que se celebrarán en la BNE los días 7 y 8 de noviembre.

Consulta aquí todas las presentaciones, coloquios y talleres 👇https://t.co/wqW0lvxZrh

— Biblioteca Nacional de España (@BNE_biblioteca) November 3, 2023

El Proyecto PhiloBiblon ha querido estar presente en esta convocatoria pública de proyectos de investigación de humanidades digitales; lo hemos hecho a través de un breve vídeo en el que se explica de forma concisa nuestro devenir pasado, nuestro trabajo actual y nuestros planes de futuro. Quedamos muy agradecidos a Lourdes Soriano, directora de BITECA, por su esmero y buen hacer en el diseño y en la elaboración.

Después de su estreno en el canal de Youtube de la BNE, subiremos la versión al canal de Youtube de PhiloBiblon, que recientemente se ha modificado para albergar diferentes vídeos de miembros de nuestro proyecto, sobre todo los relacionados con los Seminarios PhiloBiblon celebrados en años anteriores.

Para seguirnos en las redes sociales, lo mejor es descargarse nuestro enlace de link.tree, desde el que se puede acceder a todos nuestros perfiles.

De igual forma, también podrás acceder a estos enlaces si escaneas con tu teléfono o tableta el siguiente código QR.

Un saludo cordial a nuestros lectores: esperamos que nuestra participación en el #DARIAHDAY os mantenga informados de nuestras últimas investigaciones.

PhiloBiblon 2023 n. 6 (octubre): PhiloBiblon White Paper

A requirement of the NEH Foundation grant for PhiloBiblon, “PhiloBiblon: From Siloed Databases to Linked Open Data via Wikibase: Proof of Concept” (PW-277550-21) was the preparation of a White Paper to summarize its results and provide advice and suggestions for other projects that have enthusiastic volunteers but little money:

White Paper

NEH Grant PW-277550-21

October 10, 2023

The proposal for this grant, “PhiloBiblon: From Siloed Databases to Linked Open Data via Wikibase: Proof of Concept,” submitted to NEH under the Humanities Collections and Reference Resources Foundations grant program, set forth the following goals:

This project will explore the use of the FactGrid: database for Historians Wikibase platform to prototype a low-cost light-weight development model for PhiloBiblon:

(1) show how to map PhiloBiblon’s complex data model to Linked Open Data (LD) / Resource Description Framework (RDF) as instantiated in Wikibase;

(2) evaluate the Wikibase data entry module and create prototype query modules based on the FactGrid Query Service;

(3) study Wikibase’s LD access points to and from libraries and archives;

(4) test the Wikibase data export module for JSON-LD, RDF, and XML on PhiloBiblon data,

(5) train PhiloBiblon staff in the use of the platform;

(6) place the resulting software and documentation on GitHub as the basis for a final “White Paper” and follow-on implementation project.

A Wikibase platform would position PhiloBiblon to take advantage of current and future semantic web developments and decrease long-term sustainability costs. Moreover, we hope to demonstrate that this project can serve as a model for low-cost light-weight database development for similar academic projects with limited resources.

PhiloBiblon is a free internet-based bio-bibliographical database of texts written in the various Romance vernaculars of the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance. It does not contain the texts themselves; rather it attempts to catalog all their primary sources, both manuscript and printed, the texts they contain, the individuals involved with the production and transmission of those sources and texts, and the libraries holding them, along with relevant secondary references and authority files for persons, places, and institutions.

It is one of the oldest digital humanities projects in existence, and the oldest in the Hispanic world, starting out as an in-house database for the Dictionary of the Old Spanish Language project (DOSL) at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in 1972, funded by NEH. Its initial purpose was to locate manuscripts and printed texts physically produced before 1501 to provide a corpus of authentic lexicographical material for DOSL. It soon became evident that the database would also be of interest to scholars elsewhere; and a photo-offset edition of computer printout was published in 1975 as the Bibliography of Old Spanish Texts (BOOST). It contained 977 records, each one listing a given text in a given manuscript or printed edition. A second edition followed in 1977 and a third in 1984.

PhiloBiblon was published in 1992 on CD-ROM, incorporating not only the materials in Spanish but also those in Portuguese and Catalan. By this time BOOST had been re-baptized as BETA (Bibliografía Española de Textos Antiguos), while the Portuguese corpus became BITAGAP (Bibliografia de Textos Antigos Galegos e Portugueses) and the Catalan corpus BITECA (Bibliografia de Textos Antics Catalans, Valencians i Balears). PhiloBiblon was ported to the web in 1997; and the web version was substantially re-designed in 2015. PhiloBiblon’s three databases currently hold over 240,000 records.

All of this data has been input manually by dozens of volunteer staff in the U.S., Spain, and Portugal, either by keyboarding or by cutting-and-pasting, thousands of hours of unpaid labor. That unpaid labor has been key to expanding the databases, but just as important, and much more difficult to achieve, has been the effort to keep up with the display and database technology. The initial database management system (DBMS) was FAMULUS running on the Univac 1110 at Madison, a flat-file DBMS originally developed at Berkeley in 1964. In 1985 the database was mapped to SPIRES (Stanford Public Information Retrieval System) and then, in 1987, to a proprietary relational DBMS, Revelation G, running on an IBM PC.

Today we continue to use Revelation Technology’s OpenInsight on Windows, the lineal descendent of Revelation G. We periodically export data from the Windows database in XML format and upload it to a server at Berkeley, where the XTF (eXtensible Text Framework) program suite parses it into individual records, indexes it, and serves it up on the fly in HTML format in response to queries from users around the world. The California Digital Library developed XTF as open source software ca. 2010, but it is now in the process of being phased out and is no longer supported by the UC Berkeley Library.

The need to find a substitute for XTF caused us to rethink our entire approach to the technologies that make PhiloBiblon possible. Major upgrades to the display and DBMS technology, either triggered by technological change or by a desire to enhance web access, have required significant grant support, primarily from NEH, eleven NEH grants from 1989 to 2021. We applied for the current grant in the hope that it would show us how to get off the technology merry-go-round. Instead of seeking major grant support every five to seven years for bespoke technology, this pilot project was designed to demonstrate that we could solve our technology problems for the foreseeable future by moving PhiloBiblon to Wikibase, the technology underlying Wikipedia and Wikidata. Maintained by Wikimedia Deutschland, the software development arm of the Wikimedia Foundation, Wikibase is made available for free. With Wikibase,we would no longer have to raise money to support our software infrastructure.

We have achieved all of the goals of the pilot project under this current grant and placed all of our software development work on GitHub (see below). We received a follow-on two-year implementation grant from NEH and on 1 July 2023 began work to map all of the PhiloBiblon data from the Windows DBMS to FactGrid.

❧ ❧ ❧

For the purposes of this White Paper, I shall focus on the PhiloBiblon pilot project as a model for institutions with limited resources for technology but dedicated volunteer staff. There are thousands of such institutions in the United States alone, in every part of the country, joined in national and regional associations, e.g., the American Association for State and Local History, Association of African American Museums, Popular Culture Association, Asian / Pacific / American Archives Survey Project, Southeastern Museums Conference. Many of their members are small institutions that depend on volunteer staff and could use the PhiloBiblon model to develop light-weight low-cost databases for their own projects. In the San Francisco Bay Area alone, for example there are dozens of such small cultural heritage institutions (e.g., The Beat Museum, GLBT Historical Society Archives, Holocaust Center Library and Archives, Berkeley Architectural History Association.

To begin at the beginning: What is Linked Open Data and why is it important?

What is Wikibase, why use it, and how does it work?

Linked Open Data (LOD) is the defining principle of the semantic web: “globally accessible and linked data on the internet based on the standards of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), an open environment where data can be created, connected and consumed on internet scale.”

Why use it? Simply, data has more value if it can be connected to other data, if it does not exist in a silo.

Wikibase in turn is the “free software for open data projects. It connects the knowledge of people and organizations and enables them to open their linked data to the world.” It is one of the backbone technologies of the LOD world.

Why use it? The primary reason to use Wikibase is precisely to make local or specialized knowledge easily available to the rest of the world by taking advantage of LOD, the semantic web. Conversely, the semantic web makes it easier for local institutions to take advantage of LOD.

How does Wikibase work? The Wikibase data model is deceptively simple. Each record has a “fingerprint” consisting of a Label, a Description, and an optional Alias. This fingerprint uniquely identifies the record. It can be repeated in multiple languages, although in every case the Label and the Description in the other languages must also be unique. Following the fingerprint header comes a series of three-part statements (triples, triplestores) that link a (1) subject Q to an (2) object Q by means of a (3) property P. The new record itself is the subject, to which Wikibase assigns automatically a unique Q#. There is no limit, except that of practicality, to the number of statements that a record can contain. They can be input in any order, and new statements are simply appended at the end of the record. No formal ontology is necessary, although having one is certainly useful, as librarians have discovered over the past sixty years. Must records start with a statement of identity, e.g.: Jack Keraouc (Q160534) [is an] Instance of (P31) Human (Q5).[1] Each statement can be qualified with sub-statements and footnoted with references. Because Wikibase is part of the LOD world, each record can be linked to the existing rich world of LOD identifiers: Jack Keraouc (Q160534) in the Union List of Artist Names ID (P245) is ID 500290917.

Another important reason for using Wikibase is the flexibility that it allows in tailoring Q items and P properties to the needs of the individual institution. There is no need to develop an ontology or schema ahead of time; it can be developed on the fly, so to speak. There is no need to establish a hierarchy of subject headings, for example, like that of the Library of Congress as set forth in the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH). LC subject headings can be extended as necessary or entirely ignored. Other kinds of data can also be added:

New P properties to establish categories: nicknames, associates (e.g., other members of a rock band), musical or artistic styles);

New Q items related to the new P properties (e.g., the other members of the band).

There is no need to learn the Resource Description Access (RDA) rules necessary for highly structured data, such as MARC or its eventual replacement, BIBFRAME. This in turn means that data input does not need persons trained in librarianship.

How would adoption of Wikibase to catalog collections, whether of books, archival materials, or physical objects, work in practice? What decisions must be made? The first decision is simply whether (1) to join Wikidata or (2) set up a separate Wikibase instance (like FactGrid).[2] The former is far simpler. It requires no programming experience at all and very little knowledge of data science. Joining Wikidata simply means mapping the institution’s current database to Wikidata through a careful analysis of the database in comparison with Wikidata. For example, a local music history organization, like the SF Music Hall of Fame, might want to organize an archive of significant San Francisco musicians.

The first statement in the record of rock icon Jerry García might be Instance of (P31) Human (Q5); a second statement might be Sex or Gender (P21) Male (Q6581097); and a third, Occupation (P106) Guitarist (Q855091).

Once the institutional database properties have been matched to the corresponding Wikidata properties, the original database must be exported as a CSV (comma separated values) file. Its data must then be compared systematically to Wikidata through a process known as reconciliation, using the open source OpenRefine tool. This same reconciliation process can be used to compare the institutional database to a large number of other LOD services through Mix n Match, which lists hundreds of external databases in fields ranging alphabetically from Art to Video games. Thus the putative SF Music Hall of Fame database might be reconciled against the large Grammy Awards (5700 records) database of the Recording Academy.

Reconciliation is important because it establishes links between records in the institutional database and existing records in the LOD world. If there are no such records, the reconciliation process creates new records that automatically become part of the LOD world.

One issue to consider is that, like Wikipedia, anyone can edit Wikidata. This has both advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that outside users can correct or expand records created by the institution. The disadvantage is that a malicious user or simply a well-intentioned but poorly informed one can also damage records by the addition of incorrect information.

In the implementation of the new NEH grant (2023-2025), we hope to have it both ways. Our new user interface will allow, let us say, a graduate student looking at a medieval Spanish manuscript in a library in Poland to add information about that manuscript through a template. However, before that information can be integrated into the master database, it would have to be vetted by a PhiloBiblon editorial committee.

The second option, to set up a separate Wikibase instance, is straightforward but not simple. The Wikibase documentation is a good place to start, but it assumes a fair amount of technical expertise. Matt Miller (currently at the Library of Congress) has provided a useful tutorial, Wikibase for Research Infrastructure , explaining how to set up a Wikibase instance and the steps required to go about it. Our programmer, Josep Formentí, has made this more conveniently available on a public GitHub repository, Wikibase Suite on Docker, which installs a standard collection of Wikibase services via Docker Compose V:

Wikibase

Query Service

QuickStatements

OpenRefine

Reconcile Service

The end result is a local Wikibase instance, like the one created by Formentí on a server at UC Berkeley as part of the new PhiloBiblon implementation grant: PhiloBiblon Wikibase instance. He used as his basis the suite of programs at Wikibase Release Pipeline. Formentí has also made available on GitHub his work on the PhiloBiblon user interface mentioned above. This would serve PhiloBiblon as an alternative to the standard Wikibase interface.

Once the local Wikibase instance has been created, it is essentially a tabula rasa. It has no Properties and no Items. The properties would then have to be created manually, based on the structure of the existing database or on Wikidata. By definition, the first property will be P1. Typically it will be “Instance of,” corresponding to Instance of (P31) in Wikidata.

The Digital Scriptorium project, a union catalog of medieval manuscripts in North American libraries now housed at the University of Pennsylvania, went through precisely this process when it mapped 67 data elements to Wikibase properties created specifically for that project. Thus property P1 states the Digital Scriptorium ID number; P2 states the current holding institution, etc.

Once the properties have been created, the next step is to import the data in a batch process, as described above, by reconciling it with existing databases. Miller explains alternative methods of batch uploads using python scripts.

Getting the initial upload of institutional data into Wikidata or a local Wikibase instance is the hard part, but once that initial upload has been accomplished, all data input from then on can be handled by non-technical staff. To facilitate the input of new records, properties can be listed in a spreadsheet in the canonical input order, with the P#, the Label, and a short Description. Most records will start with the P1 property “Institutional ID number” followed by the value of the identification number in the institutional database. The Cradle or Shape Expressions tools, with the list of properties in the right order, can generate a ready-made template for the creation of new records. Again, this is something that an IT specialist would implement during the initial setup of a local Wikibase instance.

New records can be created easily by inputting statements following the canonical order in the list of properties. New properties can also be created if it is found, over time, that relevant data is not being captured. For example, returning to the Jerry García example, it might be useful to specify “rock guitarist”(Q#) as a subclass of “guitarist.”

The institution would then need to decide whether the local Wikibase instance is to be open or closed. If it were entirely open, it would be like Wikidata, making crowd-sourcing possible. If it were closed, only authorized users could add or correct records. PhiloBiblon is exploring a third option for its user interface, crowdsourcing mediated by an editorial committee that would approve additions or changes before they could be added to the database.

One issue remains, searching:

Wikibase has two search modes, one of which is easy to use, and one of which is not.

- The basic search interface is the ubiquitous Google box. As the user types in a request, the potential records show up below it until the user sees and clicks on the requested record. If no match is found, the user can then opt to “Search for pages containing [the search term],” which brings up all the pages in which the search term occurs, although there is no way to sort them. They show up neither in alphabetical order of the Label nor in numerical order of the Q#.

- More precise and targeted searches must make use of the Wikibase Query Service, which opens a “SPARQL endpoint,” a window in which users can program queries using the SPARQL query language. SPARQL pronounced “sparkle,” is a recursive acronym for “SPARQL Protocol And RDF Query Language,” designed by and for the World Wide Web Consortium (WC3) as the standard language for LOD triplestores, just as SQL (Structured Query Language) is the standard language for relational database tables.

SPARQL is not for the casual user. It requires some knowledge of SPARQL or similar query languages as well as of the specifics of Wikibase items and properties. Many Wikibase installations offer “canned” SPARQL queries. In Wikidata, for example, one can use a canned query to find all of the pictures of the Dutch artist Jan Vermeer and plot their current locations on a map, with images of the pictures themselves. In fact, Wikidata offers over 400 examples of canned queries, each of which can then serve as a model for further queries.

How, then, to make more sophisticated searches available for those who do not wish to learn SPARQL?

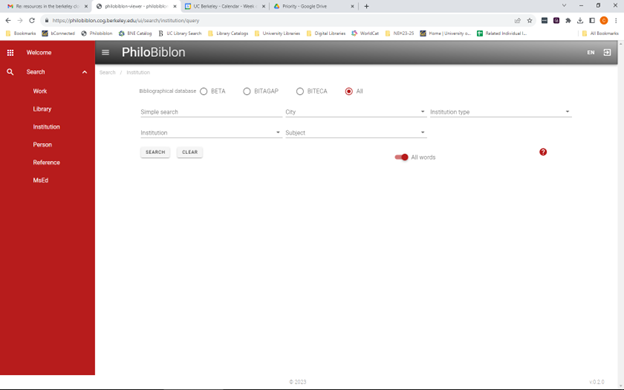

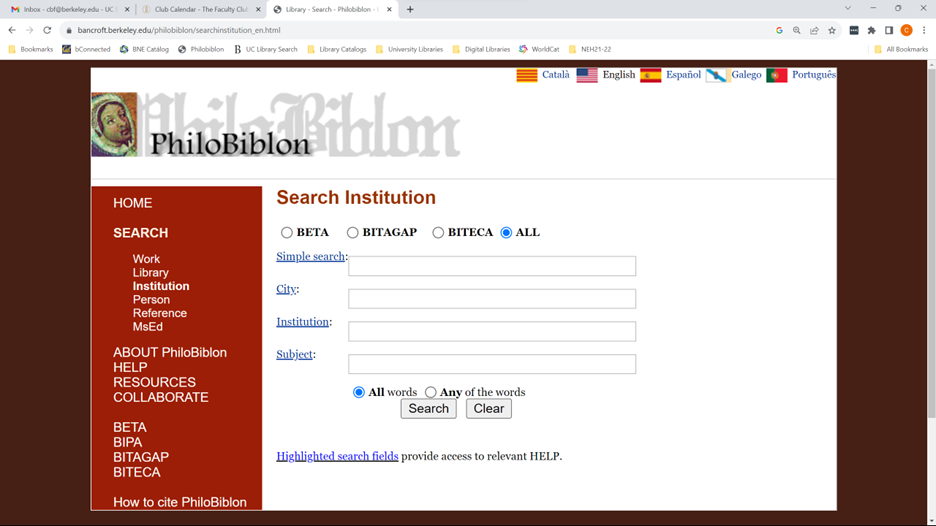

For PhiloBiblon we are developing masks or templates to facilitate searching for, e.g., persons, institutions, works. Thus, the institutions mask allows for searches for free text, the institution, its location, its type (e.g., university), and subject headings:

This mimics the search structure of the PhiloBiblon legacy website:

The use of templates does not, however, address the problem of searching across different types of objects or of providing different kinds of outputs. For example, one could not use such a template to plot the locations and dates of Franciscans active in Spain between 1450 and 1500. For this one needs a query language, i.e., SPARQL.

We have just begun to consider this problem under the new NEH implementation grant. It might be possible to use a Large Language Model query service such as ChatGPT or Bard as an interface to SPARQL. A user might send a prompt like this: “Write a SPARQL query for FactGrid to find all Franciscans active in Spain between 1450 and 1500 and plot their locations and dates on a map and a timeline.” This would automatically invoke the SPARQL query service and return the results to the user in the requested format.

Other questions and considerations will undoubtedly arise for any institution or project contemplating the use of Wikibase for its database needs. Nevertheless, we believe that we have demonstrated that this NEH-funded project can serve as a model for low-cost light-weight database development for small institutions or similar academic projects with limited resources.

Questions may be addressed to Charles Faulhaber (cbf@berkeley.edu).

[1] For the sake of convenience, I use the Wikidata Q# and P# numbers.

[2] For a balanced discussion of whether to join Wikidata or set up a local Wikibase instance, see Lozana Rossenova, Paul Duchesne, and Ina Blümel, “Wikidata and Wikibase as complementary research data management services for cultural heritage data.” The 3rd Wikidata Workshop, Workshop for the scientific Wikidata community, @ ISWC 2022, 24 October 2022. CEUR_WS, vol-3262.

Charles Faulhaber

University of California, Berkeley

Free large-format scanning for UC Berkeley students, faculty, and staff

Members of the UC Berkeley community can now get up to 10 free large-format scans per semester at the Earth Sciences & Map Library! This can include maps or other large, flat materials. Scans over the free allotment are $10 each. For walk-in patrons not affiliated with the university, the cost is $25 per scan. Get more information about large-format scanning, or visit the library to start your scanning project.

Members of the UC Berkeley community can now get up to 10 free large-format scans per semester at the Earth Sciences & Map Library! This can include maps or other large, flat materials. Scans over the free allotment are $10 each. For walk-in patrons not affiliated with the university, the cost is $25 per scan. Get more information about large-format scanning, or visit the library to start your scanning project.“Robert Cox: Sierra Club President 1994-96, 2000-01, and 2007-08, on Environmental Communications and Strategy,” oral history release

New oral history: “Robert Cox: Sierra Club President 1994-96, 2000-01, and 2007-08, on Environmental Communications and Strategy”

Video clip from Robert Cox’s oral history on the Sierra Club’s environmental justice work with Jesus People Against Pollution (JPAP) in 1994

Robert Cox is a scholar and a gentleman. He also has a fire burning in his belly for protecting nature, confronting injustice, and empowering people, which fueled his long-time leadership in environmental politics, strategy, and influential communication. Robbie Cox served three times as president of the national Sierra Club in 1994-96, 2000-01, and 2007-08. He is Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH), and as a scholar of activist rhetoric, Cox helped found the academic field of environmental communication.

Robbie and I recorded nearly eleven hours of his life history over Zoom during five interview sessions in September 2020, during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Robbie’s inspiring stories of environmental activism produced a 253-page transcript, which includes an appendix with several photographs. The stories that Robbie shared in his oral history also emphasized the incredibly high stakes for our present moment of environmental politics, rhetoric, and civic engagement.

Cox was born in September 1945, in Hinton, West Virginia, where his early influences included roaming Appalachian forests and rivers as well as his family’s history of union organizing and work toward social justice. He was recruited to the debate team at the University of Richmond where, from 1963 to 1967, he studied communication, philosophy, history, and religion while also participating in civil rights protests. In 1970, Cox earned his Ph.D. in classical rhetoric studies from the University of Pittsburgh with a dissertation on the rhetorical structures of the Vietnam antiwar movement in which he actively participated. From 1971 to 2010, Cox was a Professor in the Department of Communication at UNC-CH where he helped establish the field of environmental communication and focused his research and teaching on argumentation, rhetorical theory, and social movements. Cox married Professor Julia Wood in 1975 when she also joined the UNC-CH faculty in the Department of Communication.

Video clip from Robert Cox’s oral history on first joining the Sierra Club in 1979

Upon Dr. Wood’s suggestion, Cox joined the Sierra Club in 1979 and, over time, he earned leadership positions at every level in the Club: as chair of the Research Triangle Group, as chair of the North Carolina Chapter, and as an elected member to the national board of directors for most years between 1993 and 2013, including three times as president of the national Sierra Club. Cox made significant contributions to passage in the US Congress of the North Carolina Wilderness Bill, to the Sierra Club’s early engagements in the environmental justice movement, to restructuring both the Club’s internal governance and its volunteer structure, as well as helping lead Sierra Club engagements in national politics, particularly during his times as Club president. In this oral history, Cox discusses all of the above, with a focus on leveraging influential communication and strategy, while also sharing his experiences hiking and trekking in the Himalayas, in the mountains of Europe, and in the Appalachian Mountains.

Robbie Cox’s oral history is significant for detailing the environmental activism and political strategies of one of the most influential volunteers in recent Sierra Club history. Some of the themes throughout Robbie’s oral history include the profoundly democratic nature of the Sierra Club, details on the Club’s geographically diverse grassroots activism, as well as numerous ways that volunteer environmentalists work together to shape state and national legislation. Robbie also reconstructed the ways he balanced his double life as UNC professor with his life as an environmental activist, especially through his work in Sierra Club media campaigns. He recounted his decades as a nationally elected volunteer leader in the Sierra Club, as told through the perspective of an academic scholar of rhetoric and communications. And throughout, Robbie shared stories of direct action for environmental causes at all levels of Sierra Club engagement, from local to national.

Video clip from Robert Cox’s oral history on passing the North Carolina Wilderness Act in 1984

The in-depth, life-history approach used in this oral history reveals ways that Robbie’s personal influences and his engagements in the Sierra Club evolved over time. For instance, Robbie’s family history of labor activism instilled in him the power of people and the importance of social justice. Similarly, his participation on debate teams shaped substantially his education and academic work, while also playing a central role throughout his life as a political and environmental activist. Robbie’s interview also explored the Sierra Club’s and his own personal engagements with environmental justice, including his attendance at the First National People of Color Environmental Justice Leadership Summit in 1991, his leveraging of media in the national Sierra Club’s partnership with “Jesus People Against Pollution” in Mississippi, as well as his experiences on toxic tours of colonias in Matamoro, Mexico, along with other actions against the negative results of neoliberal free trade agreements.

Robbie also shared insider details on several significant moments in the Sierra Club’s recent history. He recounted the Club’s severe financial crises in the 1990s that resulted in his work to reorganize the Club’s internal governance through Project Renewal as well as the Club’s volunteer structures via Project ACT. Robbie recounted his central role in the Sierra Club’s efforts to combat the de-regulatory and anti-environmental Congressional agenda in wake of Newt Gingrich’s Republican take-over of Congress in the 1990s, as well as Robbie’s personal role in securing the Sierra Club’s endorsement of Al Gore, for whom Robbie campaigned in 2000. Robbie also detailed the central role he played in the Groundswell Sierra campaign in the early 2000s to resist a take-over of the Sierra Club by anti-immigration and white supremacist forces. And as the world warms and the seas rise, Robbie discussed ways that the Sierra Club has confronted the compounding crises of climate change in the twenty-first century. Robbie’s decades of environmental activism provides a lens on ways the environmental movement has evolved over time from its early focus on wild lands, to concerns about human health, to engagement on issues of environmental justice, to the modern complexities of climate change. Robbie also reflects on the contemporary Sierra Club’s internal and external challenges in its ongoing work for equity, inclusion, and justice.

Video clip from Robert Cox’s oral history on delivering to Congress the Environmental Bill of Rights with 1.2 million signatures in 1995

Back in the summer of 2020, when I spoke with Carl Pope, former Sierra Club executive director, to prepare for Robbie’s oral history, Pope recalled Robbie’s exceptional leadership and effectiveness. When “Professor Cox” first won election to the national Sierra Club board of directors in the 1990s, Pope described Robbie’s presence as “immediately noticeable.” Pope told me how Robbie used his expertise in rhetoric to unify people and advance proposals for environmental action. “You could see Robbie work at a board meeting,” Pope remembered. “When he wanted to get the board to agree, he would offer some initial proposal tentatively, then let folks respond to it and let the room talk. Then he’d come back in and make the same proposal, but he changed two words to see if that worked. He’d keep playing with the proposal and make changes rhetorically, until he got something that would work for everyone.” The Sierra Club’s board of directors come increasingly from a variety of backgrounds across the United States. All directors are volunteers, not employed staff, but like much of the Sierra Club staff, many Club directors consider themselves to be full-time environmental activists. As Carl Pope noted, however, most Sierra Club directors “are not professional communicators. People would talk past each other. Robbie’s skill on the board lubricated that process, which was phenomenally helpful. If anyone wanted to get something done, you asked Robbie.” Indeed, Robbie Cox got things done.