1922: The year that changed Brazilian art

In year of Brazil’s independence centenary, the winds of change blew through the country’s art world and changed it forever, writes Lucinda Hawksley.

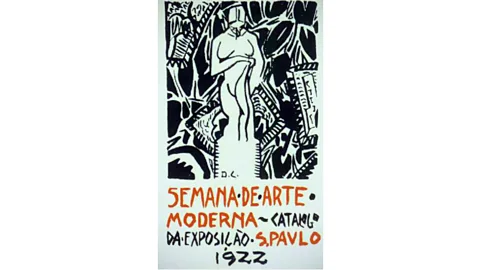

For the people of Brazil, 1922 was a landmark year. It marked a full century of independence from Portugal – and it was also the year that put Brazilian art on the international map. An idea grew up from the artists’ studios of São Paolo: to dedicate a week to modern art, to run alongside the government-organised centenary celebrations.

For seven days, artists constructed, deconstructed, performed, sculpted, gave lectures, read poetry and created some of the most avant-garde works ever seen in Brazil. The emphasis of the week was modernism – lectures about modern art were given, new styles of music were played and difficult poems were read aloud. Among the works showcased at the Modern Art Week was poetry by Mario de Andrade, controversial art nouveau paintings by Di Cavalcanti (an artist associated with the English decadence movement and Oscar Wilde) and sculptures by Victor Brecheret. These were rounded, strong monumental figures with an emphasis on naturalism and anatomy – figures that seemed too human and too sexual to a world as yet unused to ‘modern’ art.

Today the Semana de Arte Moderna of 1922 is recognised as a pivotal moment in the development of modern art. At the time, however, it was greeted with expressions of anger, horror, fear or derision. There were stories of performers being pelted with missiles by shocked audiences, and critics wrote angrily about works they couldn’t comprehend.

One of the most pronounced features of the works displayed was a desire to rid Brazil of imported art, literature, ideas and ideology. The country was celebrating 100 years of freedom from Portuguese oppression – so why, the artists wanted to know, was European art still considered by most to be superior to the work of Brazilian artists?

In Europe at that time, art had moved from the ages of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism through to Vorticism, Futurism, Cubism and the earliest stirrings of Surrealism. World War I had crushed sentimentality and ushered in the Machine Age. In 1922, Europe was still attempting to rebuild itself after years of conflict, and each country was attempting to salvage its own cultural identity, trying to work out what was real and what had been created by the propaganda of wartime.

That’s not to say that Brazilian artists cut themselves off from European influences. Many Brazilians had family connections with Europe – Brazil was a true melting pot of identities – and several of the country’s most important 20th-Century artists still continued to visit Europe, most notably Paris. They went to study and to discover what was happening in other artistic communities. Yet on their return to Brazil, these artists no longer produced mere imitations of what they had seen in Europe, as their predecessors in the 19th and early 20th Centuries had done. Instead, they had gained the freedom to use the skills, techniques and experiences gained overseas to create their own uniquely Brazilian works.

Di Cavalcanti may have been inspired by the illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley, but his works take on a magical sensationalism and colour palette that is distinctly Brazilian, certainly not English. When Lygia Clark returned to Rio de Janeiro in the 1950s, after two years in Paris, she began looking at her art from a new perspective. Instead of seeing it from the point of view of the artist creating it, she began to think in terms of what it would be like to be the viewer observing the work. This can be seen perfectly in her series of Bichos (‘creatures’), hinged sculptures that seem to entice the viewer to move each section into a new formation, to make the work their own.

Polished concrete

Throughout the 1930s and ’40s, while much of the world was still in a state of flux about what exactly constituted ‘modern’ art, Brazilian society was quick to embrace it. Individual artists or works could still cause controversy and hostility, but the idea of modern art remained appealing and new museums were soon being talked about for São Paolo and Rio de Janeiro. To those looking from the outside – journalists, foreign politicians and visitors from abroad – Brazil was leading the way forward, and this new style of art and artistic expression was slowly seeping into the cultural identity of the country.

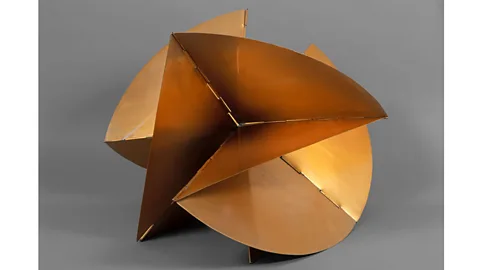

In 1951, Brazil took another bold artistic step: the creation of the first art biennale to be held outside Venice. It was founded by Brazilian-Italian industrialist Ciccillo Matarazzo and held in São Paolo. The following year, a seminal exhibition, entitled Ruptura (Rupture), was held at the Museum of Modern Art in São Paolo. The exhibition and its manifesto marked a break with past and a new style: ‘Concrete Art’, in which the organic and the geometric would sit side-by-side. The word ‘concrete’ was used to emphasise that the art was driven by concepts, not plucked from the abstract – no matter how abstruse the results might seem to the viewer. This was a new style of art from the modernist 1920s and ’30s works. In the 1950s abstract and geometric art was the art of the moment.

Artists in both cities made the interpretation of the Ruptura manifesto their own: a manifesto which declared that figurative art was exhausted, and that it no longer had any meaning in the modern world. Artists wanted to work from their instincts and primal feelings, rather than simply just trying to reproduce what they saw in front of them. Abandoning figurative art may be considered commonplace today, but at the time this was groundbreaking and extremely provocative. Travelling via Abstraction and the wide-ranging influences of Cubism, it was an easy step to the stripped-down minimalism of geometric art.

Hands on

Artists including Geraldo do Barros, Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape and Hélio Oiticica used the very essence of Brazil to create their works: materials from the earth itself, metals mined in Brazil, wood grown there, paints in the country’s colours. They used their art not only to inspire aesthetic awe, but to rail against social injustices. When Lygia Pape produced her series of Tecelares or “weavings”, she used the techniques of indigenous crafts – woodcuts and textiles – to highlight what was happening to the ‘landless’, ‘dispossessed’ indigenous people whose land was being parcelled up and sold by and between the government, industrialists and capitalists.

Painter, photographer and furniture designer Geraldo do Barros loved to the play around with the concepts of what was and wasn’t abstract and what was and wasn’t hand made. He would produce painstaking works by hand but would attempt to make them look mass-produced. In this he was commenting on the lost craftsmanship of Brazil, talents that were being steamrollered out of existence by industrialisation. He liked to trick the eye and the mind to make people question what was and wasn’t art.

One of the leading artists of the Neo-Concrete movement, which grew dramatically in popularity following the Ruptura exhibition, was Franz Weissmann. Together with Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape and Hélio Oiticica he created works that mutated with every exhibition, in materials that could be manipulated – and which made as much use of the space that the materials encompassed as of the concrete shapes themselves. In his Neo-Concrete Column of 1957, Weissmann chose to use iron, an essential part of Brazilian industry, which seems to hold the spaces inside in place – as if the viewer is looking at captured air.

Hélio Oiticica wanted to bring art off the walls of the galleries and not only right into the room, but preferably into the hands of the people who saw it. Oiticica was especially concerned with what would happen to art in the future, after the artist’s death. He wanted his work to endure and to change if necessary, according to who owned, touched and loved it.

The geometric art which grew out of Ruptura might seem to be a world away from the smooth, fleshy curves of Victor Brecheret’s sculptures and the boldly, coloured, dreamlike subjects who gazed out of Di Cavalcanti’s paintings, but the Modern Art Week of 1922 began the artistic revolution that led Brazil away from the Euro-centric art of the previous decades and into a celebration of a new geometric artistic identity. It allowed the stripped-down forms of radical geometric art to thrive in the exciting new world of the 1950s and into the future.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.