It was 40 years ago today, that Kraftwerk taught the synths to play…

The Paris launch of Kraftwerk’s career-defining album ‘The Man-Machine’ in April 1978 was the result of months of meticulous conceptualising, composing, recording and planning. The launch event itself ended with the group’s dummies positioned in compromising positions by music journalists maddened by free vodka, electronic music played at punishing volume while bathed in red light (“By the time we leave,” wrote Andy Gill in the NME at the time, “the dummy Ralf’s flies are undone, and the dummy Florian’s strides are round his ankles”). Kraftwerk themselves stood around drinking champagne for an hour before slipping away to enjoy a meal at the nearby La Coupole brasserie, and the album went on to earn them a gold disc and is now rightly considered one of the most important records of all time.

When it was released, ‘The Man-Machine’ was taken as a concept album of sorts. In some quarters it was considered further evidence of the sinister machinations of the German will to power. After all, here was an almost impenetrably strange German band who had three concept albums under their belts already. There was one about the joys of driving on the Autobahn which, according to many British critics at the time weened on Commando comics, was probably about authoritarianism and Hitler. The next was about radioactivity, which was also probably about authoritarianism and Hitler; and then there was one about Europe and trains, which was less obviously about authoritarianism and Hitler, but was probably about those things anyway. I mean, just look at them on the cover of that album.

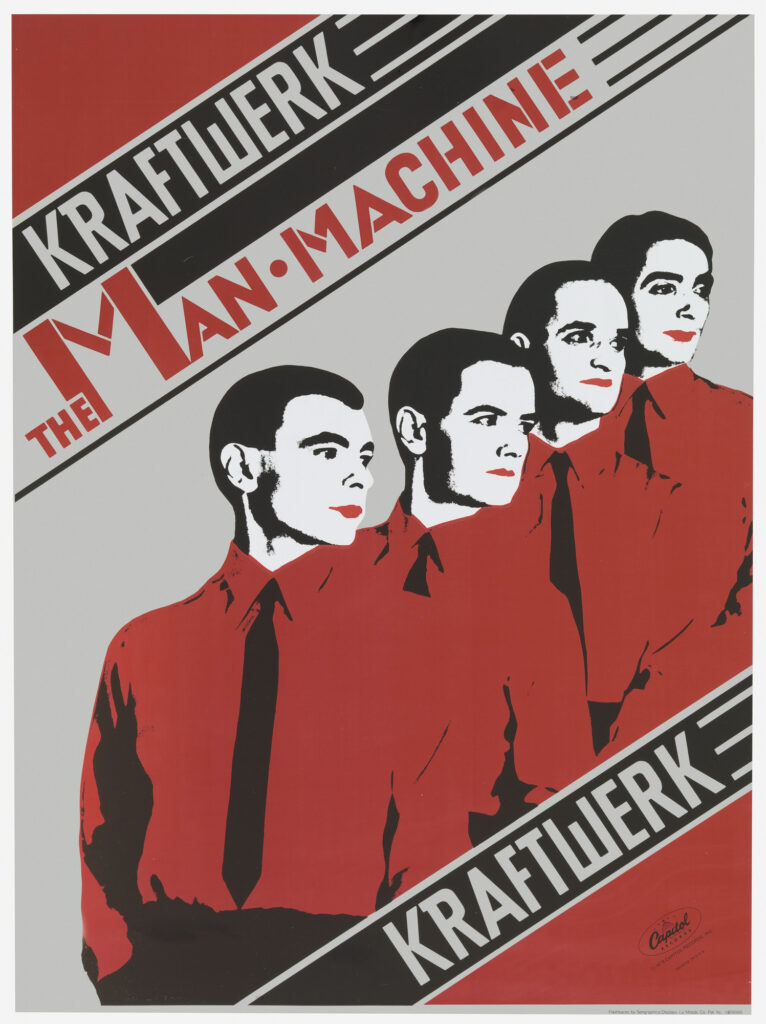

And here they were in the sparkly new post-punk world of 1978 with yet another album draped in meaningful imagery, but this time it was all about how robots were going to take over the world, with the band photographed on the cover dressed in uniforms, striking distinctly regimented poses, designed with a colour palette of red, black and white. All of which, when you think about it, is a bit like Hitler, but in the future. With robots.

To be fair, the British music press did calculate that Kraftwerk weren’t being entirely serious, and on whole didn’t take them particularly seriously. The band’s central joke, if you could call it a joke, appeared to be something along the lines of “You think Kraftwerk is cold, emotionless and robotic, well, here you are then… we are the robots!”.

Kraftwerk’s look for ‘The Man-Machine’, which continues to define them to this day in pop culture, took its inspiration from David Bowie’s 1976 tour, according to Wolfgang Flür.

“I can remember David’s concert blew our minds,” says Flür. “Bowie had distanced himself from his colourful outfits and chameleon image from the past and went on stage in a black suit and white shirt. The lighting was in different white tones; cold neon white, powerful and dazzling halogen-white, smooth bulb-white. Different nuances were used for each song. The whole event appeared to me to be more like a serious classical concert than a pop concert. It made a big impression on me. I can remember it led to our own style with black trousers and red shirts, black ties which were equipped later with a row of red blinking LED lamps, lit up by batteries each of us had in our trouser pocket.”

The Kraftwerk-are-actually-robots schtick was nailed down once and for all at the Paris press launch for the album. The showroom dummies 2.0 iteration of the band’s robots sported the band members’ faces at a cost of 4,000 DM per mannequin (around £2,000 in 1978, £10,000 today). It was an expensive gimmick, but it paid off. The idea that the robots could stand in for photo shoots alone was probably worth the expense for Ralf and Florian, neither of whom were particularly at ease in front of the camera.

The dummies had been made in Munich, with Ralf and Florian commissioning a distinguished mannequin company called Obermaier to build them. Towards the end of 1977, Kraftwerk took the train to Munich, where the company photographed each member and then modelled their faces from plasticine to create the moulds for the heads which were then cast in plastic.

Sound-wise, ‘The Man-Machine’ was crystal clear, Kraftwerk’s most sonically pure outing to date. The album itself was the third to be recorded at the Kling Klang studio at Mintropstrasse 16, Düsseldorf, where the sequencers would be set and run for hours at a time. Florian was more concerned with texture and sound design, with Ralf and Karl Bartos making the melodies, Bartos earning a co-writing credit on every track, as he did on every subsequent Kraftwerk album until his departure in 1990.

Maxime Schmitt, the band’s label manager in France at the time, gave Pascal Bussy a glimpse of the process for his book ‘Man, Machine And Music’: “Often they would all sit behind the console, letting the machines run by themselves for one or two hours… from time to time Florian would stand up and got to another machine and launch another sequence. It was almost closer to a traditional jam session than studio work. The following day they would listen back to the tape.”

By February 1978, ‘The Man-Machine’ was ready for mixing, and the decision was made to finish it off at Studio Rudas, a larger recording studio nearby. The mix was helmed by studio owner Joschko Rudas and Leanard Jackson (aka Leanard “Colonel Disco” Jackson), who had worked with Motown legend Norman Whitfield on big-selling disco records by Rose Royce (including the multi-platinum selling ‘Car Wash’ soundtrack album), the black psychedelic soul outfit Undisputed Truth and the explosive synth heavy funk album ‘Nytro’ by Nytro.

Kraftwerk flew Leanard in from Los Angeles to help sharpen the album’s danceability. Arriving straight from LA’s balmy blue-skied climate to Düsseldorf’s freezing February (it was a particularly cold winter) must have been a shock for him, as was the discovery that Kraftwerk were four middle class white guys. Because of the emphasis on dance rhythms in the tracks he’d been sent, he had assumed black musicians had been responsible.

Recorded and mixed, and with the El Lissitzky-inspired artwork prepared, the album was ready for the pressing plants and in April an event was organised to launch the album to the music press.

One spring evening, at Le Ciel De Paris, a fancy nightclub on the 56th floor of the Montparnasse Tower (it’s still in business today, though much remodelled, if you fancy a visit), journalists and other interested parties were treated to vodka and caviar, and the album was played at high volume (enough for NME’s Andy Gill to complain it was too loud), the entire place bathed in red by the many lights strategically placed around the room, which Gill felt created an “alienating, oppressive environment”.

On a wall, the film ‘Metropolis’ was projected, intercut with the promo film for ‘The Robots’, in which Kraftwerk and their plastic doppelgängers merged into one. It offered some tantalising glimpses inside Kling Klang; the four of them standing over a mixing console and adjusting sliders (robotically, natch), and Wolfgang and Florian lurking over their two-inch 24-track tape machine, switching it on and off (like robots would). There was a similar event held in New York.

‘Die Mensch-Maschine’ was released on red vinyl in Germany, and in English as ’The Man-Machine’ on black vinyl elsewhere. There was no tour to promote the album, with Kraftwerk opting to stay at home in their Kling Klang bunker for the next three years cooking up their next electronic statement which would see the light of day in 1981.

Perhaps because of the lack of a tour, the album failed to chart in the UK until 1982, when it went into the Top 10 off the back of the hit single, ‘The Model’. “The Man Machine stands as one of the pinnacles of 70s rock music,” concluded Gill when he reviewed the album at the end of April. “And one which I doubt Kraftwerk will ever surpass.”

‘The Man-Machine’ was released worldwide on 19 May 1978