An Interview with C.C. Beck

The following interview is a compilation of a series of interviews I conducted with Charles Clarence Beck in the middle and late 1980s. The interviews were both conducted by mail (I would mail him a list of questions, he would type his responses and mail them back from me, whereupon I would concoct follow-up questions to be mailed back to him) and by phone. Too, Beck annotated a good deal of his autobiographical writings for me to refer to and use. In conducting the interviews, I had in mind packaging a book-length overview of Beck’s career in comics, a career I had tremendously enjoyed and one I was eager to further enshrine.

C. C. Beck at a 1982 comics convention

But Beck was not always as cooperative as I might have hoped; he was forthcoming one time, close-mouthed and curmudgeonly the next. (Surprising to me, we were better able to forge ahead in our mailed interviews than we were in our phone sessions; on the phone he seemed more concerned with parrying my every thrust. For example, he told me how thoroughly enjoyed his work on Captain Marvel. But when I later mentioned that he had had fun with his work, he rebuked me, chastising me for having an overly rosy view about the hard work that is drawing comics, “as some sort of fantasy land where weird artists and weirder writers cavort around like fauns in a field of daisies,” as he put it to me. But through the mail, I was able to pose more pointed questions to him—and he was more willing to write candidly.) His written reply to my suggestion that I travel to interview him in person was vintage Beck: “The idea of meeting in person, so popular today when everyone is clamoring for peace talks and get-togethers, is rather foolish; usually nothing is accomplished except to arrange for another meeting at which again nothing will be accomplished.” When I tried to develop a profile of Beck as a human being, he said, “One thing I want to bring to your attention is that my work is much more important than my personal life. Interviews today takegreat delight in probing into the personalities of people, describing their clothing and their hair and what kind of glasses they wear and all that trivia. To me, this is hogwash. Such stuff is written by people just out of a course in writing run by a half-ass professor who believes in ‘caring’ and ‘feeling’ and ‘sharing’ and all that folderol. Phooey on such crap, I say. I’m a professional artist and writer and hope that you are, too. Let’s leave that sob-sister stuff to People magazine and such publications. Or DC.”

Elsewhere, Beck vehemently rejected any efforts on my part to allow readers to become acquainted with C.C. Beck, the man: “I have no sympathy for writers and artists who gabble about ‘art’ and ‘feeling’ and ‘emotion’ and ‘caring’ and all that garbage that is so popular today. This is the mark of the dilettante, the poseur, not of the professional artist. I have always considered myself to be a professional and hope that [these interviews] will make this clear. I’d hate to come across as another old nut who never knew what he was doing until other people told him.”

Throughout our work, Beck strenuously avoided references to DC, whose treatment of him he perceived as shabby; through the years it obviously continued to rankle him. Any mention I made of DC was met with either stony silence (on the phone) or vitriol (in the mailed interviews). As he wrote, “The less we say about DC, the better—let’s pretend they don’t exist as far as we’re concerned.” As we progressed (or failed to progress, as was sometimes the case), I was confronting an increasing sense of frustration on several fronts—a sense we shared. Beck was frequently either unable or unwilling—I often never knew which—to discuss his creative input into the character for which he is best known, Captain Marvel. I often found myself trapped in a semantic cat-and-mouse game in which Beck strove to minimize his work and his creations. (Paradoxically, he was periodically eager to move ahead with the book-packaging project itself, due in part to his acknowledgement of his own mortality—a 1987 letter to me said, “Being in the shape I’m in, I may have a stroke or a heart attack at any time, so let’s do what we can while I’m still around.”) Ultimately, though, I chose to put the book project on my professional back burner. Beck and I never “officially” called it quits on the project, and we occasionally corresponded pleasantly on a number of subjects, including, ironically, his work on Captain Marvel. I have quoted from this later correspondence in this interview, as he proved himself to be a more forthcoming correspondent once the mike was turned off, and much of what he said later helped to set the historical record straight.

When Beck died of renal failure on November 23, 1989, my inability to complete a book celebrating Beck’s life and career—to my mind, one of the most commercially and aesthetically successful in the entire history of comic books—was a source of acute regret. —Tom Heintjes

Tom Heintjes: You’ve described your hometown, Zumbrota, Minn., as “a place Walt Disney would have loved.” What in the town’s character were you referring to?

C.C.Beck: It was very much like one of those old-time, middle America places he used in his cartoons, the kind of place that doesn’t exist anymore. A simple Main Street, music in the park, wooden sidewalks. It’s what Walt would have seen as the heartland.

Heintjes: Coming from early twentieth-century, small-town Missouri, Walt probably had the same sort of experiences in terms of lifestyle.

Beck: I suspect so.

Heintjes: Although Missouri surely had warmer winters.

Beck: [Laughter] I have no doubt of that. We had some cold ones.

Heintjes: Maybe that’s why it always looked like Captain Marvel’s uniform was made of flannel, rather than a thin, skintight fabric.

Beck: I never thought of that! [laughter] Maybe you’ve got something there.

Heintjes: You were born Charles Clarence Beck on June 8, 1910—

Beck: The year Mark Twain died, incidentally.

Heintjes: —so we lost a Clemens but gained a Beck. You were the son of a preacher father and a mother who was a teacher. Did anyone in your family exhibit any artistic tendencies?

Beck: No, I was the only one, and I was always doodling, as children often do. But I kept at it for decades. [laughter] I also liked to write and play music. I learned how to play the guitar, and I played into adulthood.

Heintjes: Did you enjoy comics as a child? I assume you were becoming aware of the form at a very formative time in the evolution of the newspaper strips.

Beck: That’s right. They ran big on the page, and were very impressive. With my bad eyesight today, I can’t read the cramped strips at the size they run now.

Heintjes: What were some of your favorites?

Beck: I always favored the humor strips that were drawn in a simple style.

Heintjes: That comes as no surprise to me, frankly.

Beck: I guess not. I enjoyed Barney Google, Mutt and Jeff, The Katzenjammer Kids, Popeye and Happy Hooligan, among others. I also enjoyed Gasoline Alley because it seemed so realistic, about life in a small, slow-paced town with regular people.

Heintjes: How did your parents feel about your affection for the comics?

Beck: They didn’t mind, because there was no stigma attached to the newspaper strips like there was later to comic books. Remember, when I was growing up, there were no comic books. If I had only read comics, they might have questioned it. But I read lots of books—I was an avid reader. My parents were both educated, so we didn’t want for books, many of which were beautifully illustrated. I still have some of those very books in my home here today. I have an 1839 edition of the complete works of William Shakespeare, and I still find myself looking over the woodcuts in amazement.

Heintjes: And of course you read the plays that were sandwiched in between the woodcuts.

Beck: [laughter] Yes, several times.

Heintjes: In school, did you excel in art at a young age?

Beck: I went to a very small school with limited resources. We had virtually no art classes, but I took what I could. I wanted to learn more, but Zumbrota had no artists living there. One man who lived there was a sign painter, and he taught me what he could, but it was too different from the kind of art I wanted to do. But I did learn some things from him, which today’s young artists need to know—you can learn from all kinds of art, not just comic art. It seems like the kids today learned to draw only from comic books, not from anything else. Consequently, they can’t really draw.

Heintjes: How did you continue to educate yourself as an artist?

Beck: I checked books out from the library and studied and practiced—nothing fancy. When I was a teenager I took a correspondence course and after high school I went to art schools in Chicago and Minneapolis. Actually, I always wanted to be a writer. It’s much easier to draw then to write. But I got started early in life as an artist instead.

Heintjes: Did you go to art school with the intent to acquire the skills necessary to become a cartoonist?

Beck: Far from it. I wanted to learn art, not just cartooning. I studied the history of art and art criticism. I never studied cartooning in a formal way. I think that’s what’s wrong with a lot of cartooning today—the artists never learned anything but a cartoony style, and there’s no real substance beneath the cartoony style. But it seems to be popular, so what do I know?

Heintjes: When you finished your art school education, did you get work as an artist right away?

Beck: I finished school before the stock-market crash and the Great Depression, so work wasn’t so scarce as it would be soon. I got some work because of my lettering abilities—I’ve always worked hard at lettering, and I’m proud of it. People who know me know that I’ve always said that the lettering is more important than the art. If the lettering is illegible, what good is it? The drawings support the words in the balloons, not the other way around.

Heintjes: You wouldn’t know it to look at some of the stuff on the racks.

Beck: That’s why I don’t look at the stuff on the racks. [laughter] My first job as an artist, if you can call it that, was tracing existing, famous comic-strip characters.

Heintjes: That must have been some of the earliest comics merchandising!

Beck: There was some other stuff, but this was an interesting idea: we were tracing the characters onto handmade lampshades. It was authorized and everything, and we traced characters such as Barney Google, Sparkplug, Little Orphan Annie, Smitty and others. Those were probably the best-known ones.

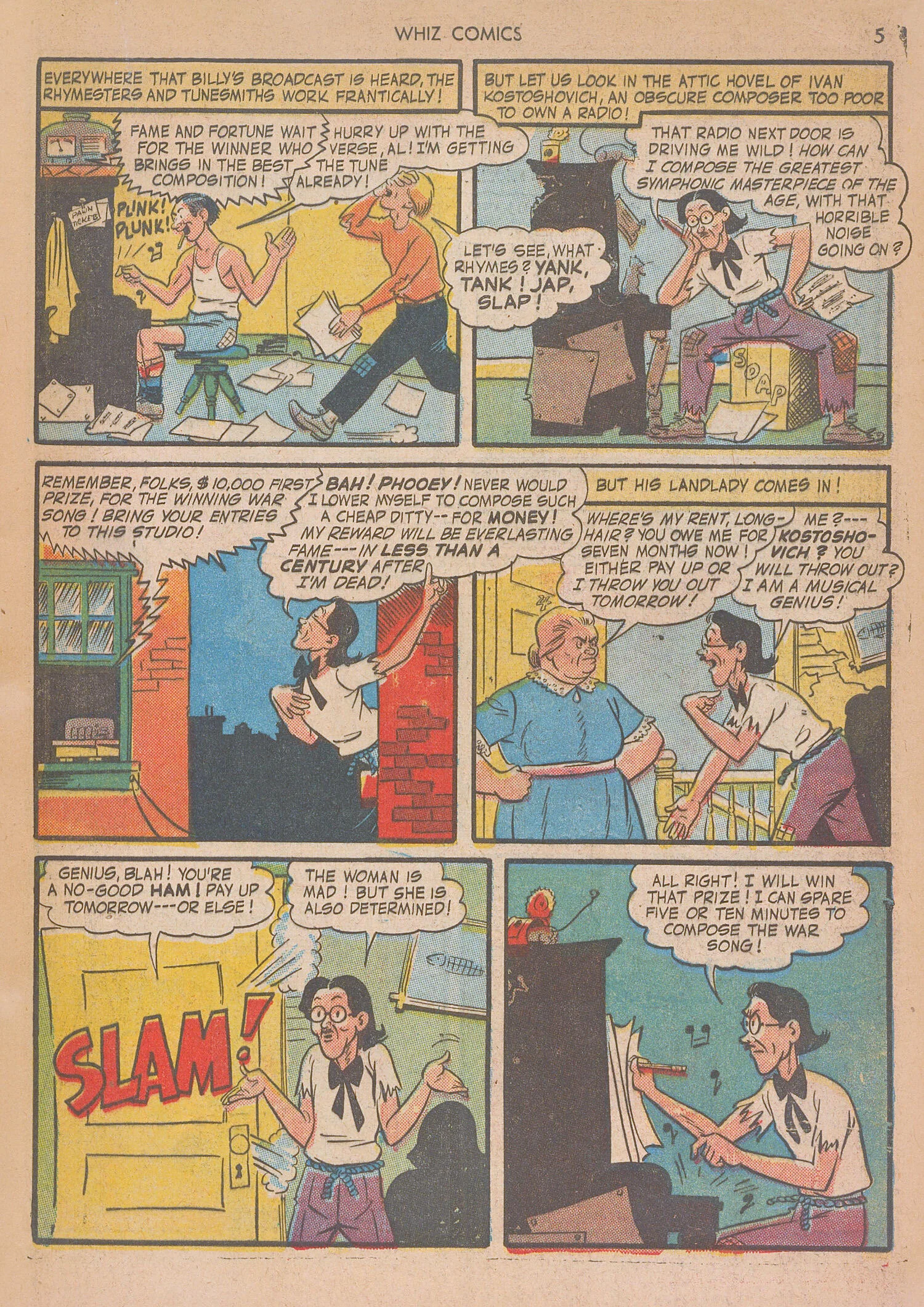

Heintjes: What was the technique you used to transfer the drawings onto lampshades?

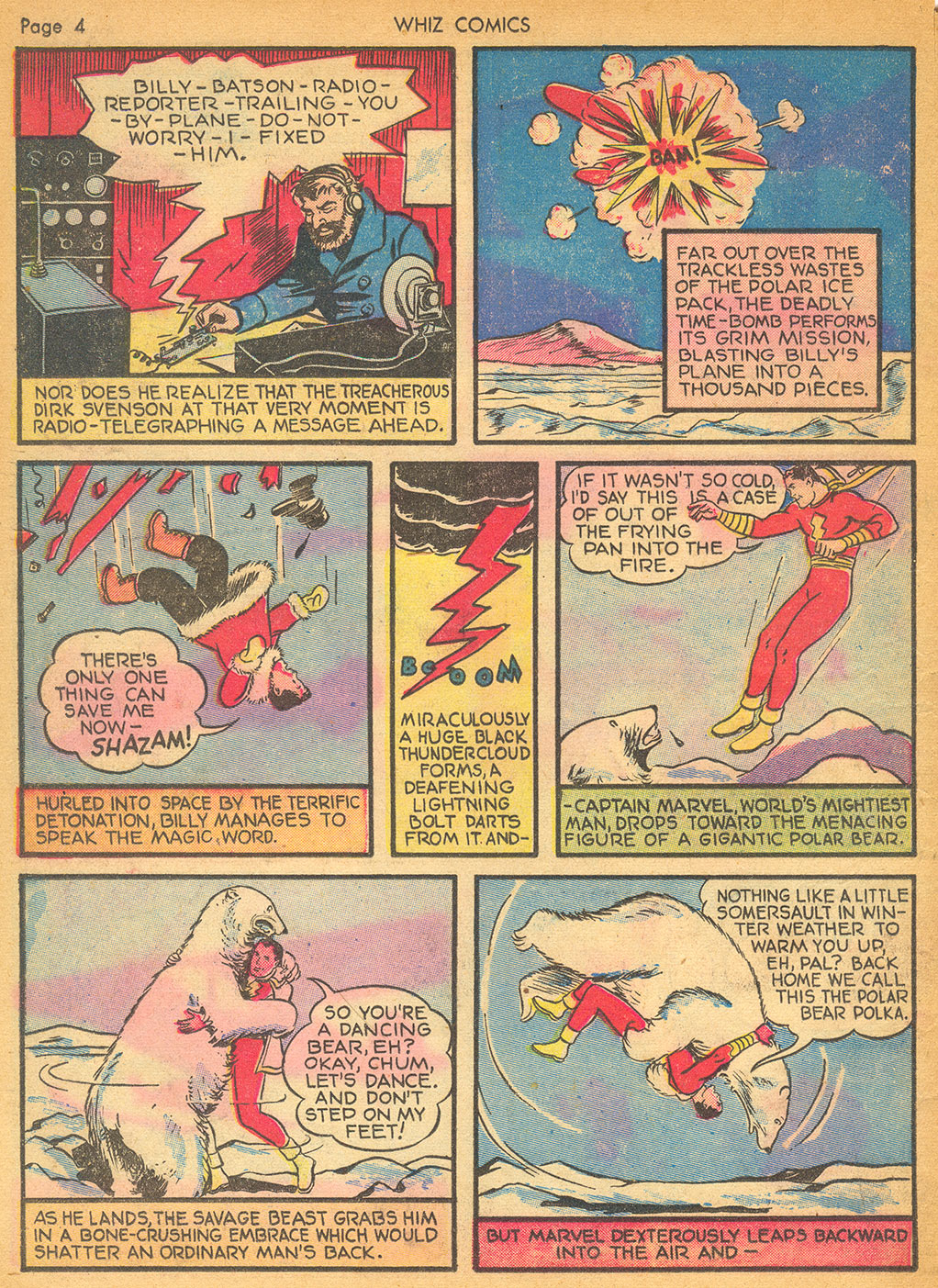

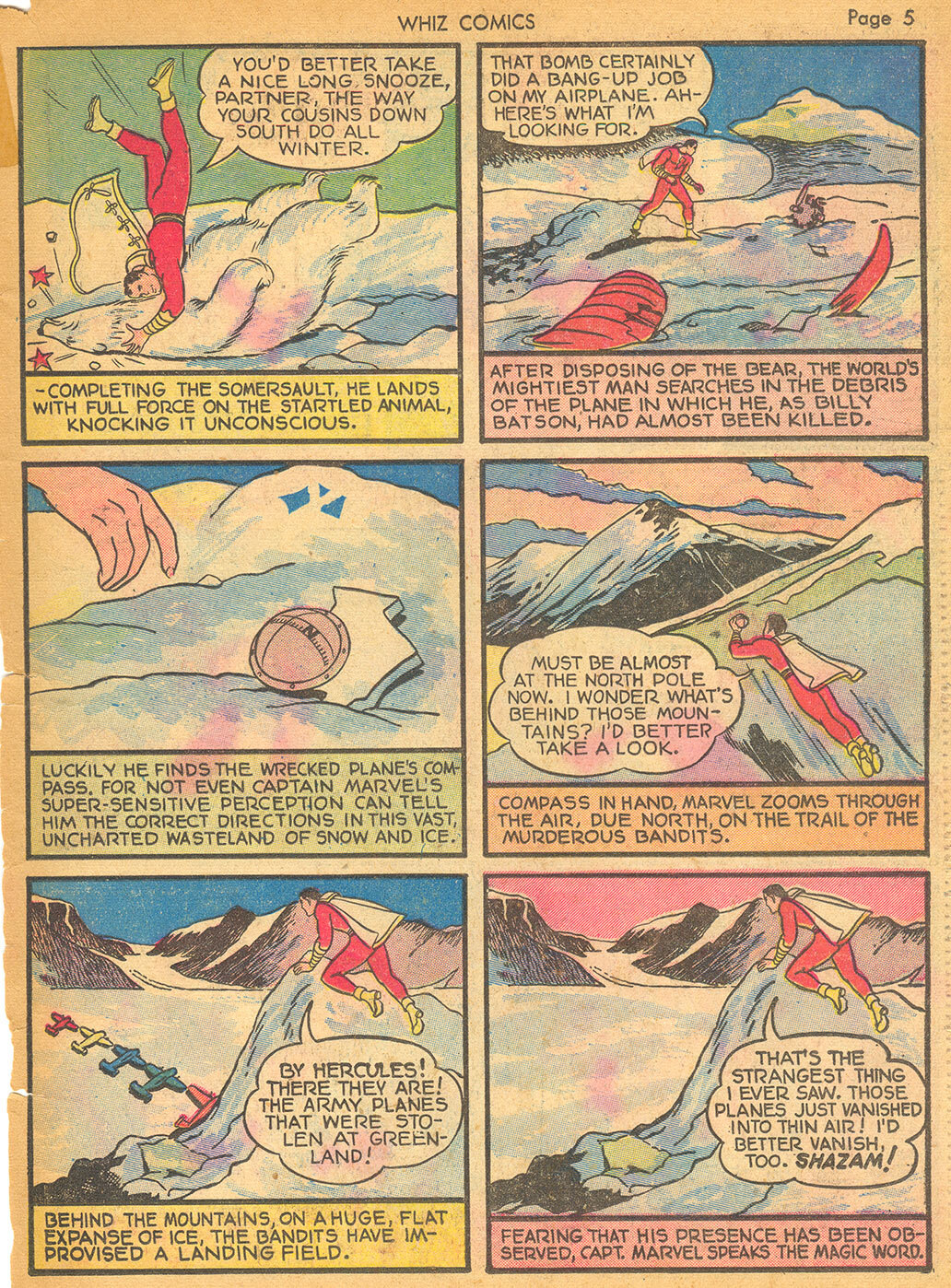

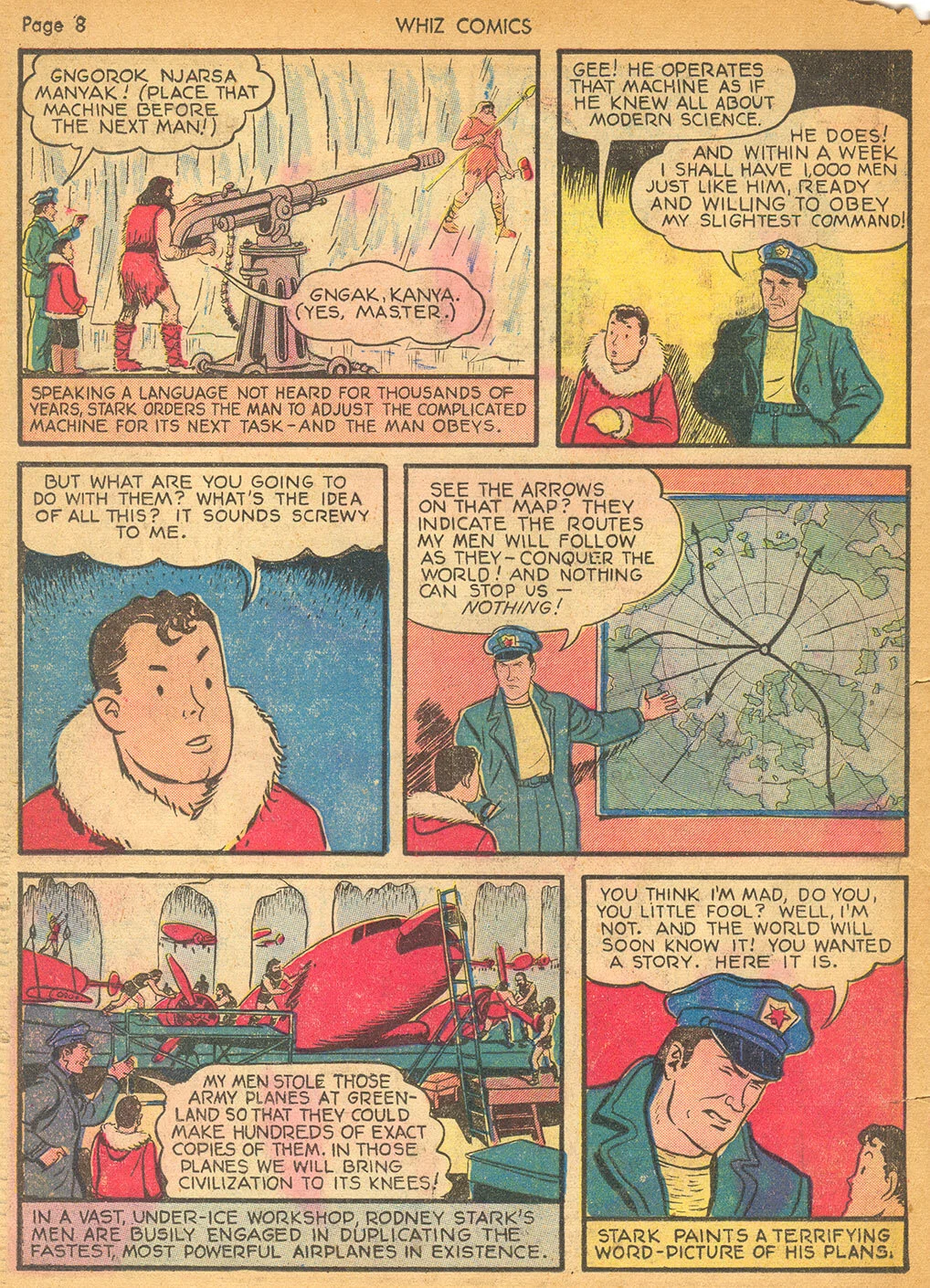

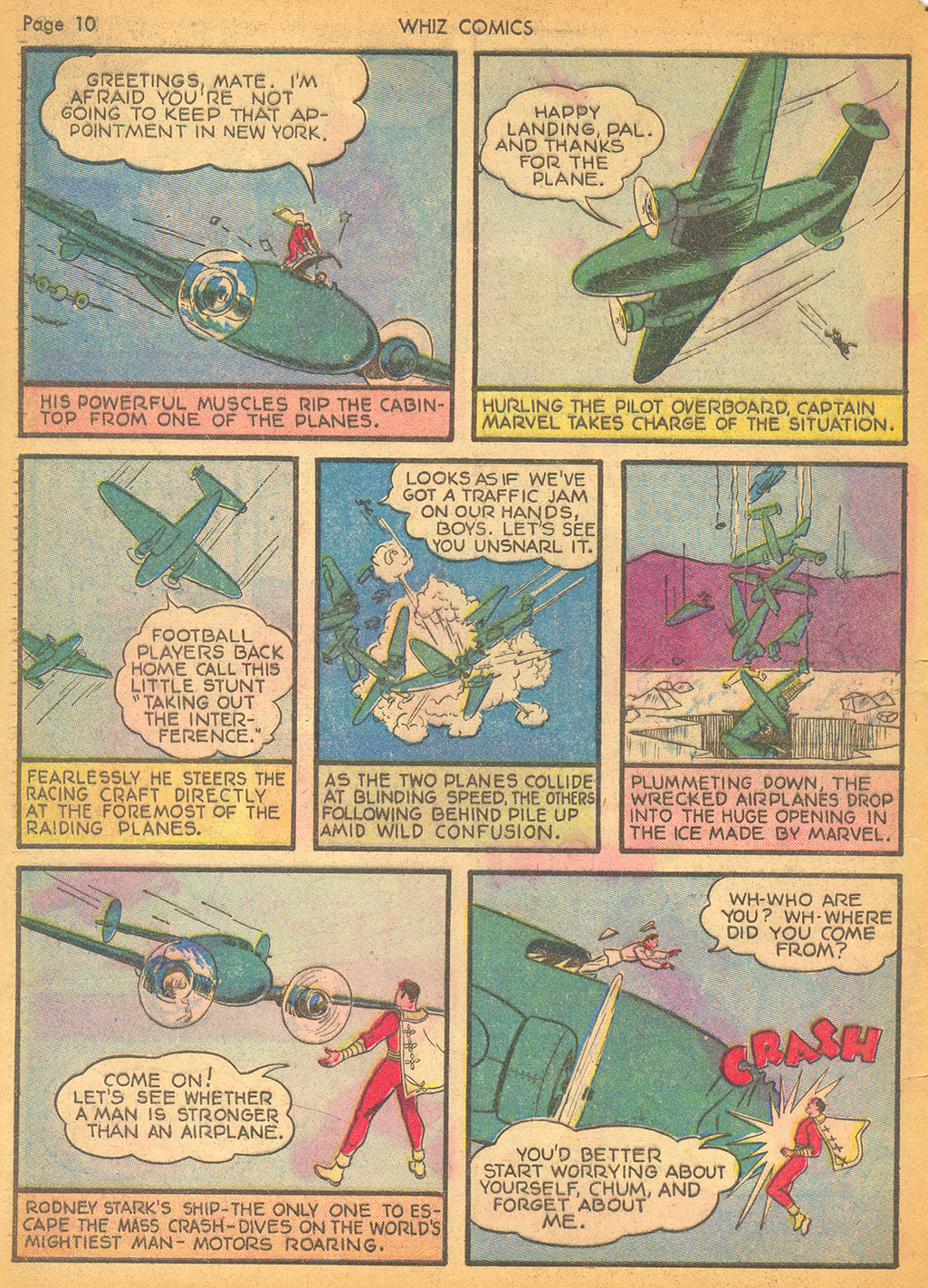

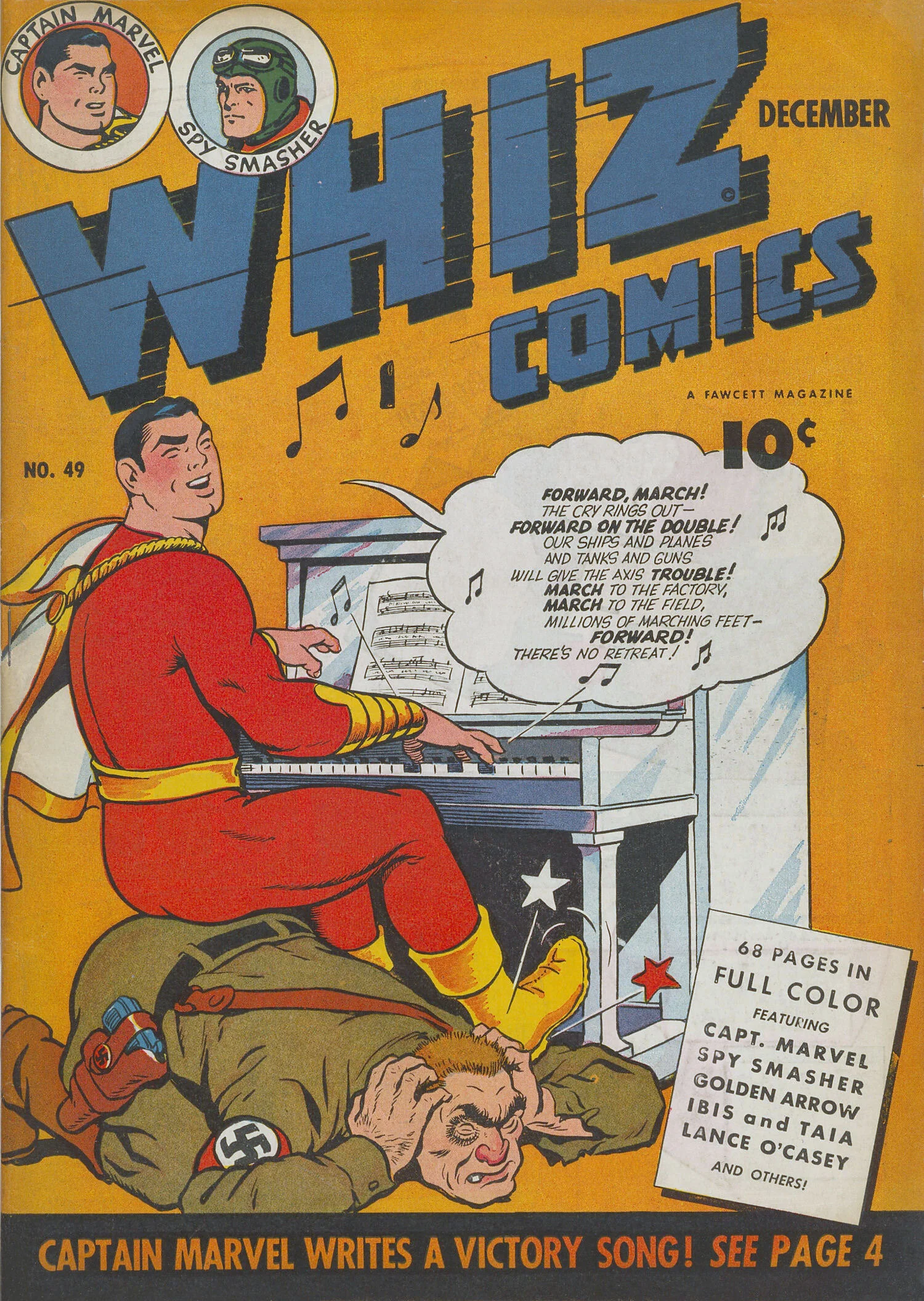

Beck: I traced the drawings, poked a lot of little holes in the lines I drew and used charcoal to transfer the art onto lampshades. This enabled me to get a job with Fawcett Publications later, working on their humor magazines—Captain Billy’s Whiz-Bang, Smokehouse Monthly and other titles. In 1939 Fawcett got into the comic-book field, and I was assigned the job of illustrating three stories in the first issue of Whiz. Bill Parker wrote all of them, featuring Captain Marvel, Ibis the Invincible and Spy Smasher. I had nothing to do with either the characters or their actions. I simply put them into picture form.

Heintjes: You say “simply” as if you’re diminishing your role.

Beck: Adding pictures to a written story, or turning a written story into picture form, as is done in comic-book work, does not increase its appeal to the imagination but diminishes it. This is because the reader is not allowed to use his own imagination to create in his mind how the characters look and act but is forced to accept an artist’s version instead.

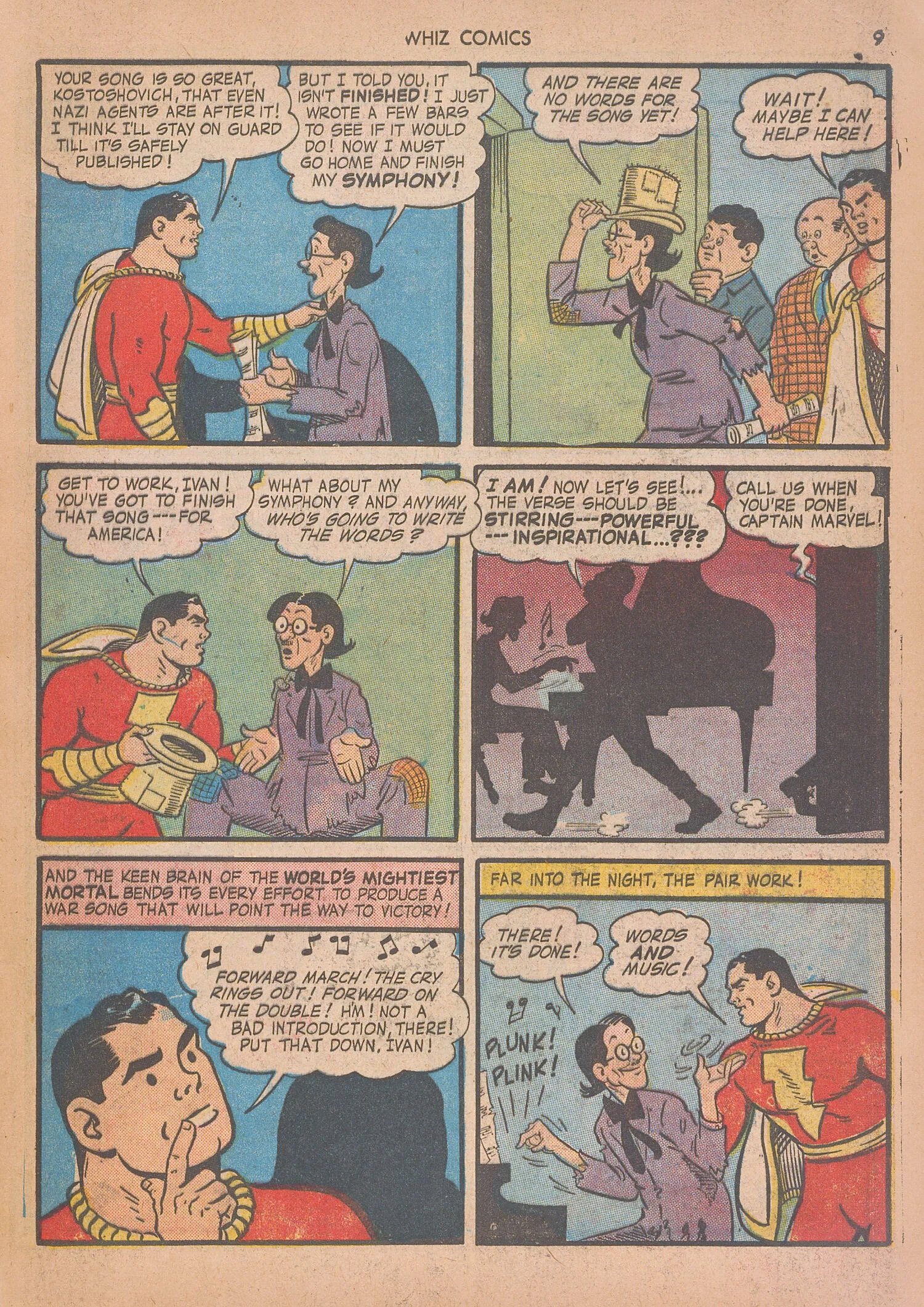

I didn’t create any of Fawcett’s characters—I was just the first person to put them into visual form. They were conceived in Parker’s mind; I was just the doctor who held them up and slapped them on their bottoms to make them draw their first breaths. For example, Parker created the word “Shazam” from the first letters of the seven gods’ names. He created the word “Sivana” by combining the name of the Indian god Siva with the word Nirvana. This gave his work more lasting value than other Golden Age comic characters and stories had, as the elements in Parker’s stories were already familiar features in our culture. When I looked at the first Captain Marvel story, I knew at once that here was a story worth illustrating. It had a beginning, a carefully constructed development of plot and characters leading to a climax and an ending, and nothing else. There was no pointless flying around and showing off, no padding, no “Look, Ma, I’m a superhero!” Out of 72 panels, Captain Marvel appeared in 18, or one-fourth. When Bill Parker and I went to work on Fawcett’s first comic book in late 1939, we both saw how poorly written and illustrated the superhero comic books were. We decided to give our reader a real comic book, drawn in comic-strip style and telling an imaginative story, based not on the hackneyed formulas of the pulp magazine, but going back to the old folk-tales and myths of classic times.

Heintjes: But at the same time, Captain Marvel eventually did adopt more of the standard superhero trappings—deflecting bullets and the like.

Beck: I’ll not deny that Captain Marvel had become a superhero in both appearance and action quite early in his career. After the first few issues Fawcett farmed out some of the work to other artists and writers, who proceeded to present the World’s Mightiest Mortal as the World’s Mightiest Imitation Superman—flying, bouncing bullets off his chest, looking like a ham actor in a shoot-’em-up movie. In addition, Fawcett created a whole line of Captain Marvel spinoff characters that were drawn by other artists in styles quite unlike mine. Finally the art director and I persuaded Fawcett to let me supervise the production of at least the Captain Marvel books. I was given the title of chief artist in charge of a studio filled with assistants and was given some name recognition, but the writers were never given any credit at all, and to this day few people are aware that comic illustrator work from scripts instead of making everything up as they go along. That’s why today I refuse to accept any credit for creating Captain Marvel, pointing out that I was merely the first—and the last—artist to draw him in his original form. I want no credit whatsoever for drawings made by artists over whom I had no control and whom, as a matter of fact, I never met, in some cases.

Heintjes: As an artist, you clearly respected the role of the writer. Since you aspired to writing, did you ever talk shop with them?

Beck: No. At Fawcett, Captain Marvel was produced by writers and artists working separately. The scripts were prepared by the editorial department, the drawings by the art department. The writers, who worked under the supervision of a managing editor, had nothing to say about the art, and the artists, who worked under the supervision of an art director, had nothing to say about the stories they were given to illustrate. In the 13 years I spent drawing Captain Marvel, I wrote only one story, about Billy’s trip to a Mayan temple, which had to be submitted in typed form and edited and approved before I was allowed to illustrate it. There was never any direct cooperation between the writers and the artists at Fawcett, but there did develop an interplay of ideas between the two departments that kept Captain Marvel changing and developing instead of getting bogged down and repeating himself tiresomely after the first few issues, as so many other comic characters did. Ralph Daigh, the editorial director at Fawcett, has said that I had complete license to change and alter scripts to suit myself. I don’t remember his saying this to me back in the days when I was drawing Captain Marvel. Either his memory or mine must be faulty.

Fawcett hired good editors, good writers and good artists and left them alone. Each man did his job and didn’t interfere with the other departments. If a man’s work was good, he stayed on the payroll, and if it wasn’t, he got fired. Otto Binder, Wendell Crowley and I did good work so we stayed on. My theory is that at Fawcett we had professional, experienced editors, writers and illustrators, while at other places they had a bunch of illiterate, untalented klutzes. We all used the principles we had learned in other work when producing the Captain Marvel stories and art, which we regarded as simply another form of popular literature. This attitude was, I believe, what enabled us to surpass the other comic-book workers of the day in the quality of our scripts and illustrations. None of us needed to copy and steal from other comic-book work. After the first few issues of Whiz had appeared, other writers and artists copied and stole our material!

Heintjes: Did you ever find yourself trying to augment the content of a story?

Beck: No. A well-written story actually will not need pictures added to it, as it will be complete by itself, and the Fawcett stories were well-written. A good writer will tell you only certain things and will not tell you others. If an illustrator draws pictures of the things the writer has already described in words, he will be merely duplicating them and will be wasting the reader’s time. If he draws things that the writer has intentionally not mentioned, he will run the risk of spoiling the story, just as he would ruin a magician’s act by drawing attention to things from which the magician has deliberately diverted his audience’s attention.

Heintjes: Would you have liked more feedback from the writers?

Beck: We got some. When the writers saw what we artists did with their stories, they were always pleased. It was, Otto once told me, like seeing your photos after they had come back from the drugstore. You saw where you had gone wrong and vowed not to repeat your mistakes. At the same time you were delighted to see where things had come out better than you had expected them to and were inspired to try new and more difficult approaches in your next stories.

As for us artists, we took each story as a challenge and gave them everything we had, never looking on our work as drudgery but enjoying every minute of it. We artists regarded the writers with respect and a certain amount of envy: it seemed so simple and easy just to sit down and in an hour or two bat out a story that would take us a week or ten days to turn into pictures! I’m sure that the writers envied us, too. To them it must have seemed childishly easy just to sit at a drawing board and draw whatever the scripts called for without thinking! Little did they know how difficult it really was.

Heintjes: Did you ever make suggestions about stories you were given?

Beck: Rarely—I wasn’t an editor. I once suggested that instead of killing Mr. Mind off, we could have him turn into a beautiful butterfly and fly away, but that idea was killed by the editorial department.

Heintjes: I guess justice wouldn’t have been served. But despite the real challenges in illustrating a story, you obviously believe in the primacy of the story.

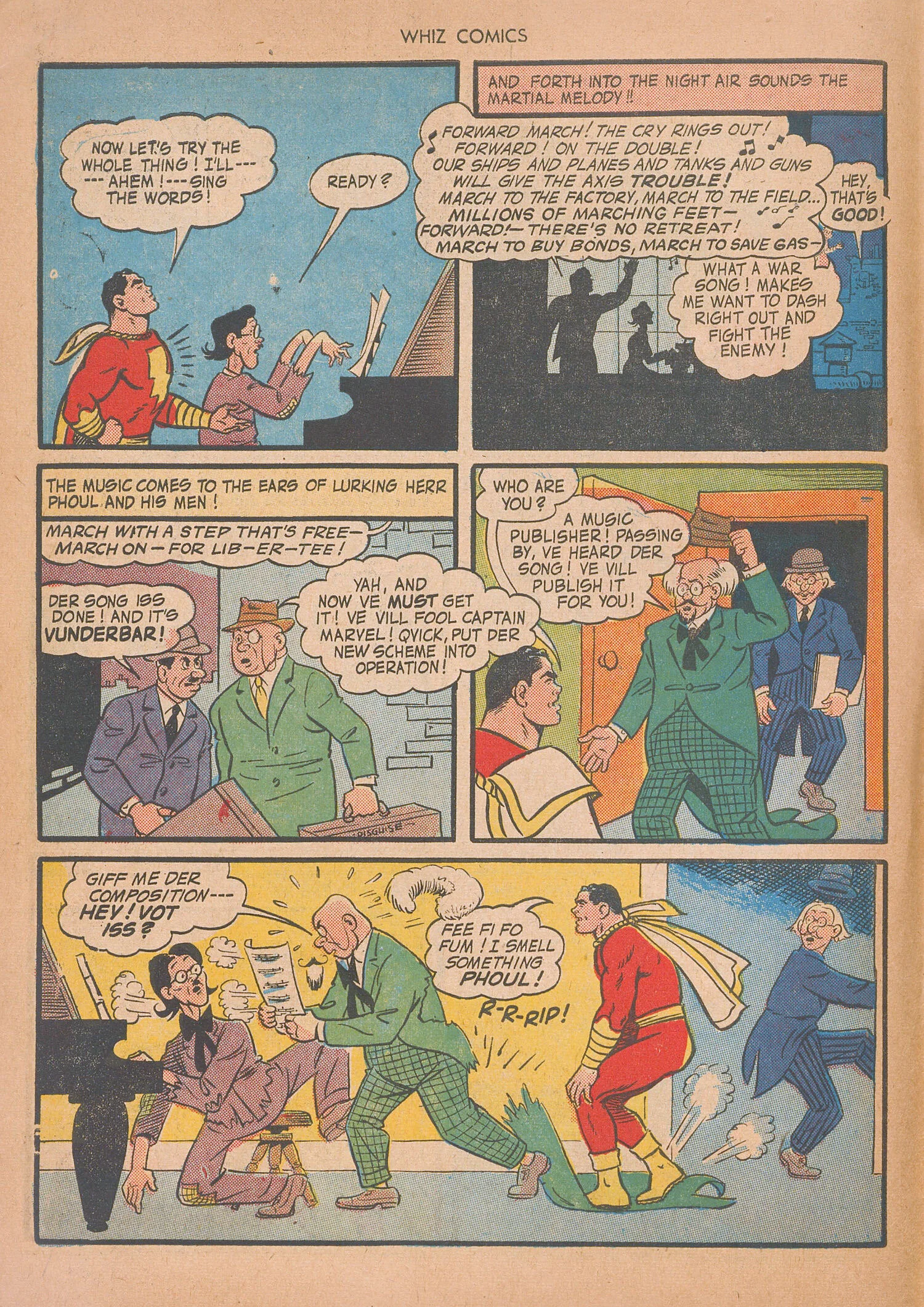

Beck When I was illustrating comic books, I always considered the stories to be what we were selling, not the pictures. I looked on myself as the director/producer of a play. My job was to hire the actors, design and produce the scenery and supply the props and costumes. I didn’t want to draw the reader’s attention to the production itself but to the story that the performers were acting out. I knew that if the story was not good, no amount of lavish overproduction and overacting would make it any better, while if the story was good my work would not make it better, but just clearer and more easy to understand by young people.

To keep readers from having their attention drawn away from the stories, I deliberately used characters, settings and props that would be instantly recognized by everyone everywhere . . . in other words, stereotypes. If the story called for a stuffy corporation head or a conservative banker, I drew a pompous man wearing a high, stiff collar and sporting a small mustache. If he was a crook I gave him a big cigar and a bigger mustache.

Heintjes: Today, it’s popular to discuss storytelling as a discipline. You had a real knack for telling a story, but I somehow doubt you overanalyzed your approach very much.

Beck: No. I knew that readers would merely glance at each of my drawings after reading the last bit of copy in each panel to keep the story moving. If, for example, a character was asleep, I didn’t show the other character shaking him and calling his name—even though the copy said that he was—but I showed the character awake and looking dazed but ready to do whatever the next panel called for. When everyday settings and props were called for, I drew them as simply as possible, then left them out in following panels. I never tipped my panels or used violent perspectives or did anything to draw attention to the drawings themselves, because I wanted readers to be aware that they were looking at drawings and hand-lettered copy and just to hear in their heads the story that was being told to them. When characters, settings and props were out of the ordinary—things that young readers might not be familiar with—I drew them clearly the first time they appeared, then left them out until they were needed again. As often as I could I used off-stage voices, sounds, people looking off-stage, pointing, running toward or away from something not seen. When violence was called for, instead of showing the violence I showed its effect, either on its victim or on its perpetrator when it backfired.

Heintjes: A straightforward approach, and one that I think contributed to the commercial accessibility of the material.

Beck: I treated my comic panels as views of a puppet show where heroes, villains and other characters came into view from the left, spoke their lines and then disappeared, to the left it they were not to be used later, to the right if they were part of an ongoing story. When characters fought, they fought each other; when they talked, they faced each other; when they ran, they ran across the stage, not out of it and into the laps of the audience. This kind of presentation was in such contrast to the superhero comics of the time that it caught on immediately and made Captain Marvel the biggest-selling comics of the Golden Age. He was a comic-strip character, as plain and simple as Harold Teen, Daddy Warbucks or Offissa Pupp. He was not—I repeat, not—a superhero. In fact, he wasn’t even the hero of the stories he appeared in.

I have always maintained—and will to my dying day—that Captain Marvel’s great success was due not to the way he was drawn but to the stories he appeared in. Fawcett employed professional writers who had to submit plots and outlines for editorial approval before the shooting scripts were written. I never knew much about what went on in Fawcett’s editorial offices, as my job was in the art department, where my assistants and I illustrated the stories we were given. We artists wrote a few stories now and then but they had to be submitted to the editors for approval and put into typed form before they were submitted. There was no “making things up as you go” at Fawcett. Comics just can’t be made that way, although many would-be cartoonists and young writers keep trying to show that they can.

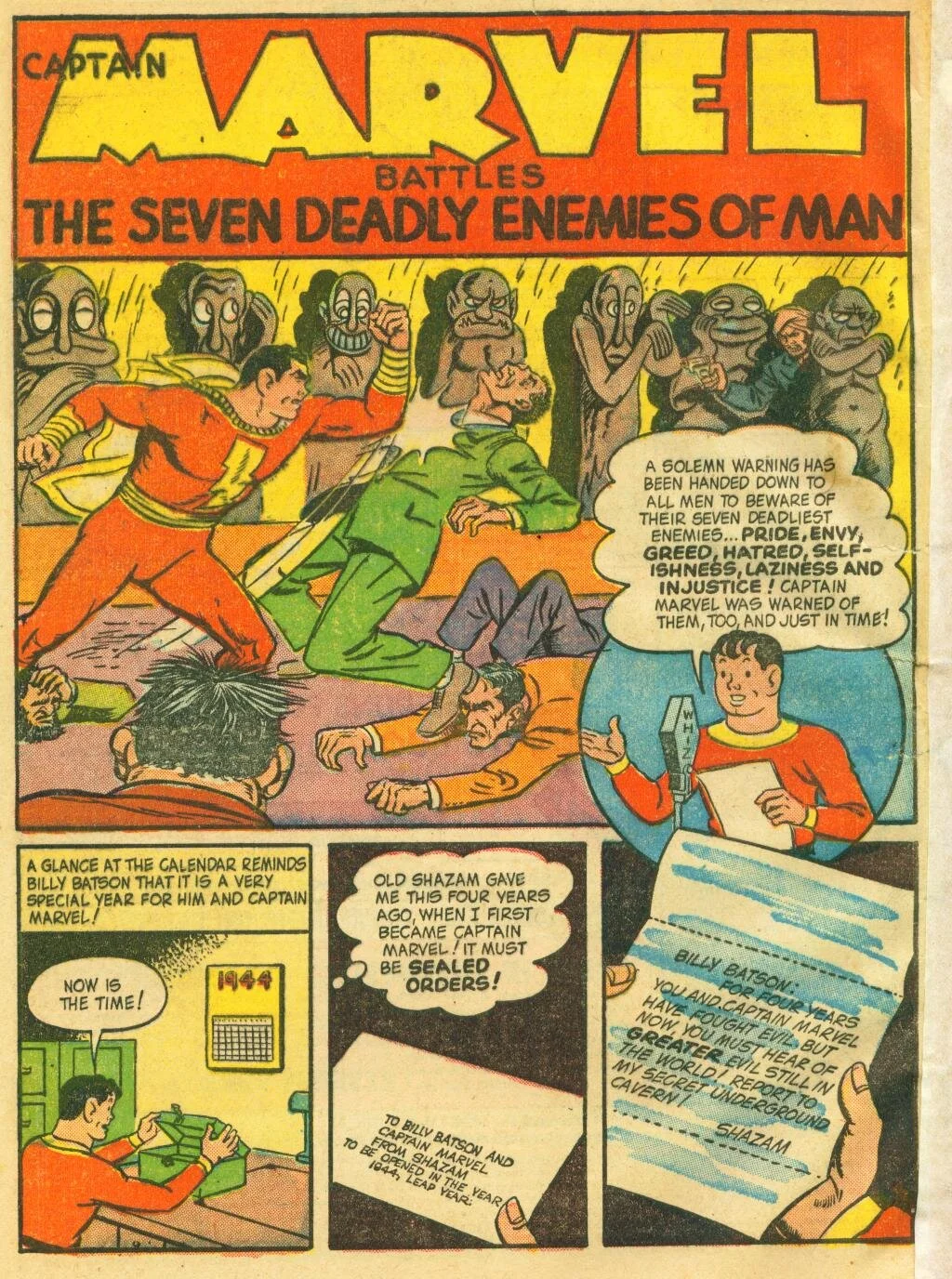

Heintjes: At Fawcett, were the writers and artists free from interference from the publisher?

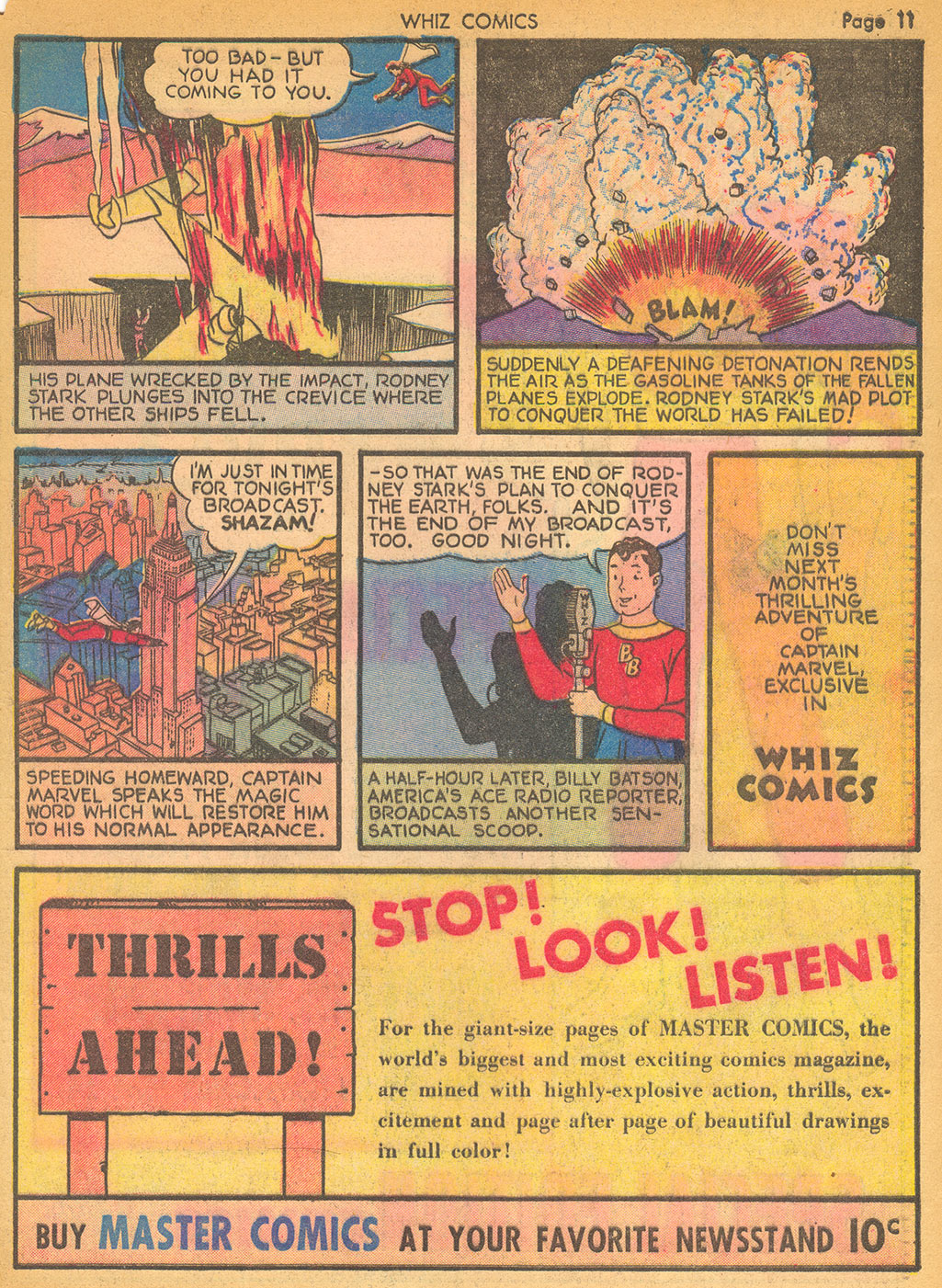

Beck: They occasionally tried to impose rules. The publisher wasn’t aware of it, but Billy Batson was the real hero of all the Captain Marvel stories, from the first issue until the last. At one time, believe it or not, the publisher sent down word to drop Billy from the stories, saying that he was only taking up room that could have been used to show Captain Marvel instead, and that he wasn’t contributing anything to the stories. Fortunately, the editors paid no attention to so ridiculous a memo and Billy Batson continued to appear in every story. Without Bill Batson, Captain Marvel would have been merely another overdrawn, one-dimensional figure in a ridiculous costume, running around beating up crooks and performing meaningless feats of strength like all the other heroic figures of the time who were, with almost no exceptions, cheap imitations of Superman. In fact, I have always felt that flying figures in picture form are silly and unbelievable, and I would much sooner have never drawn them, but the publisher insisted on them. Most of the time Captain Marvel’s ability to fly had little or nothing to do with the plots of the stories in which he appeared.

Billy Batson started every story and ended every story. In between, Captain Marvel appeared when he was needed, disappeared when he was not needed. The stories were about Billy Batson, not about the cavortings of a ridiculous superhero for whom the writers had to concoct new and more impossible demonstrations of his powers for each issue.

At least, that’s the way I saw Billy Batson, and that’s the way the writers and editors saw him. We saw Captain Marvel as a sort of big brother brought in to solve problems that the boy hero, Billy, couldn’t handle. He was bigger and stronger than Billy, but he was not a seven-foot-tall circus strongman or a creature from another world or one created by a mad scientist, as the superhero comics characters were.

The publisher also once wanted to drop Sivana, claiming the old rascal was becoming a more interesting character than Captain Marvel. The editors paid no attention to so silly an order and kept him alive and cackling. Captain Marvel Jr. was created at the publisher’s order, though. He was intended to capture the interest of younger readers and to compete with Batman’s Robin and other junior supercharacters. Personally, I thought Captain Marvel Jr. to be a sickeningly sweet, non-comic and dull character, but some readers loved him. And Mary Marvel was created to attract girl readers. In my opinion, Mary Marvel was a weak, synthetic character also created on the order of the publisher. She never came to life in the way that Billy Batson and Captain Marvel did but always seemed wooden and artificial.

Steamboat was created to capture the affection of negro readers. Unfortunately he offended them instead and was unceremoniously killed off after a delegation of blacks visited the editor’s office protesting because he was a servant, because he had huge lips and kinky hair and because he spoke in a dialect. He was always a cartoon character, not intended to be realistic at all, but he was taken seriously by some, sadly enough.

Heintjes: How much input did the writers give you on the physical appearance of the characters?

Beck: Good writers don’t give detailed accounts of the appearances, heights, weights, ages and physical features of their characters. Bill Parker’s initial script gave no description of the ancient wizard, Shazam. I drew him as a combination Moses-Merlin-good magician figure, sort of a benign semi-Biblical character. After giving his powers to Billy, old Shazam disappeared for good in the original story. Later, Shazam was revived, appeared in spirit form or was seen in flashback scenes. When drawn by other artists, he sometimes appeared evil and threatening, or like a madman. Nobody seemed to realize that I had drawn him as Captain Marvel as an old man. He had the same features, just altered by old age.

Heintjes: I want to go over the names of some of the key players at the Fawcett offices and on the Captain Marvel team. First, Pete Costanza.

Beck’s longtime Fawcett collaborator Pete Costanza

Beck: Pete Costanza was the first artist hired to assist me when Fawcett’s comic department started to expand in the latter part of 1940. We later went into partnership, and Pete was in charge of our studio in Englewood, New Jersey, while I operated out of our New York City office. Pete was an established illustrator at an early age, and I learned as much from him about story illustration as he learned from me about cartooning. When Captain Marvel was discontinued in 1953, Pete went to work for DC Comics, where he illustrated their Jimmy Olsen and other comic books.

Heintjes: In fact, you would occasionally draw Parker look-alikes into stories.

Beck: Yes, and the other characters, Mr. Morris, Sivana, Beautia and so on, were based on real people. Sivana Jr. looked pretty much like Danny Kaye, you’ll notice. Beautia looked like Betty Grable and Sivana himself was based on a druggist I had once known. Also, Tyrone Powers was the basis for Ibis the Invincible, and Errol Flynn was the model for Spy Smasher.

Heintjes: Back to key players—Otto Binder.

Beck: Otto wrote perhaps 90 percent of the Captain Marvel stories. He had been a successful science-fiction writer in the ’30s. When he came to work for Fawcett, he brought his knowledge of science fiction themes along with him, as well as an engaging sense of humor, which he injected into the Captain Marvel scripts.

Heintjes: Wendell Crowley.

Beck: Wendell Crowley was one of Fawcett’s very able editors. He had started working in the Jack Binder studio, then had worked for me. After Fawcett had hired him as editor of the Captain Marvel magazines he became the boss of us all. And a very able boss he was. Although Wendell was 10 years younger than the rest of us, and 20 years younger than Jack Binder, he never bowed to our seniority, but kept us all in our places. He knew his part in the production of comic books and took no backtalk from anyone.

Heintjes: Jack Binder.

Beck: Jack was Otto’s older brother and was an all-around artist and had been a printer, a painter and an illustrator before he got into the comic-book business. At one time he worked for me, then he took over the Mary Marvel story illustration job, which he kept until Fawcett discontinued all its comics in 1953.

Heintjes: Mac Raboy.

Beck: Mac Raboy was a frustrated fine artist forced to make his living in comic books. He had little use for cartoonish tricks and distortions and always drew as realistically as possible, being a great admirer of such artist as Hal Foster and Alex Raymond. Mac was the illustrator of the Captain Marvel Jr. stories for many years, then took over the syndicated Flash Gordon Sunday page.

Heintjes: Ed Robbins.

Beck: He was a great storyteller in the way he laid out the Captain Marvel stories for other artists to complete. He was a good cartoonist, too, and after he had left comic books, he illustrated the Mike Hammer syndicated strip for about a year.

Heintjes: How did the lawsuit affect you?

Beck: Apart from being fired when Fawcett lost, it didn’t. That was the lawyers’ job. I mean, we took it as a compliment. It meant that Captain Marvel was putting Superman out of business. If he hadn’t been any good, National wouldn’t have bothered to sue us. When the end came, they let us go like so many factory workers. I worked as a commercial illustrator again. Except for a few engravers and printers, who liked my work because it was easy to engrave and print, nobody ever paid attention to me, and my name was so unknown that I usually had to spell it out, letter by letter, for the people who made out my checks in payment. Wendell Crowley went into his father’s lumber business. Otto went to work for DC, where he was treated like a dog by Mort Weisinger.

Heintjes: How did you end up working on the character at DC when they revived him?

Beck: I believe it was Carmine Infantino, or maybe Julius Schwartz, who first contacted me. They were both amazed that I was still alive. They were sure that I had starved to death long ago. They talked me into illustrating the first few issues of the revived Captain Marvel comic, but I gave up when I realized that the stories were structureless, meaningless and totally worthless.

Heintjes: Did they indicate to you that you would have even minor input into the stories, considering that you were a force in the original stories’ success?

Beck: No. They regarded me as simply another artist who would do as told and not give them any trouble.

Heintjes: When they reprinted the original stories from the ’40s and ’50s along with the new material, did you get any sort of residuals from DC?

Beck: None. Later they sent me small amounts for some reprints, but this was done only so that I’d have no grounds for a lawsuit.

Heintjes: When you began working on the new material, was it immediately apparent to you that the arrangement was not going to be a successful one?

Beck: I could see from the start that the stories were pretty bad. They got worse and worse, and finally I refused to illustrate them. Only Sol Harrison ever spoke to me after that; the others would have nothing to do with me. I would write them letters, and they wouldn’t even answer them. They pretend I don’t exist.

Heintjes: Do you ever assess your role, historically speaking, as the chief artist behind one of comics’ great success stories?

Beck: I never think of myself as a great artist. I was better than some but worse than others—that’s all.