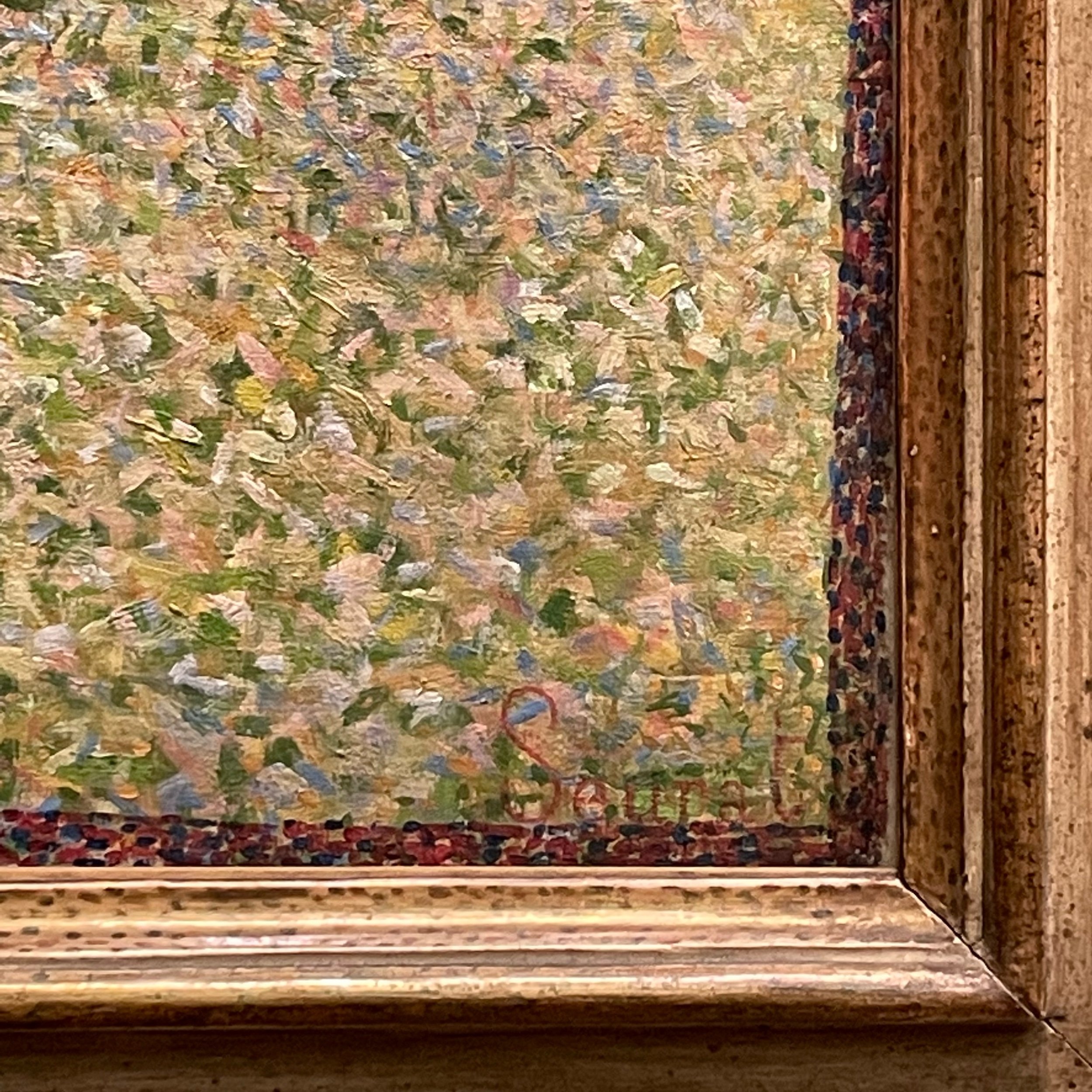

Seurat & Pointillism

Georges Seurat (1859-1891)

Various works

Oil on canvas

National Gallery

Recent news of a Seurat painting going for US$150 MILLION at auction has reminded me that Pointillism was one of the earliest “MIND. BLOWN. 🤯” moments in my art education. I can’t recall when it actually happened — maybe in my high school art class? — but reading about this technique had an incredibly powerful impact, and not just because I was never a fan of the classical arts.

Neoclassicism. Romanticism. Impressionism. Even Art Nouveau. With rare exception, almost everything pre-1900 just made me yawn. (Still does.) But Pointillism was something different. It was a radical re-think of how to use the brush. Nothing like it had ever been seen before. It was so unique that even Matisse and Van Gogh gave it a go.

The originator of the idea was Georges Seurat, basing his technique on scientific principles of how colour is perceived by the eye. He researched and experimented extensively. For the work considered to be his masterpiece, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-86), it is reported that he painted around 60 studies. SIXTY! Honestly, I don’t know how some artists do it.

That’s another thing about Seurat that blew my mind: the meticulousness. For years I’d assumed that his paintings had been created dot by dot by dot. One dot at a time, with no underlying outline or sketch. While that’s theoretically possible, it would take a super human savant to be able to paint any sort of recognisable image that way, even at a small scale. In actuality, Seurat “began work on the canvas… with a layer of small, horizontal brushstrokes in complementary colors. He next added a series of dots that coalesce into solid and luminous forms when seen from a distance.” But knowing how he did the trick doesn’t make the work any less laborious. By some accounts, Sunday Afternoon contains 220,000 individual dots of paint.

Although we now call it Pointillism, Seurat referred to his technique as Divisionism, which was somewhat ironic in that it did just that with other artists, critics and the public when he first debuted the work. Then for a relatively brief moment it inspired his contemporaries to experiment and refine the form. I’d argue that the works by Camille Pissarro and Théo van Rysselberghe in London’s National Gallery are some of the strongest in the genre. Eventually the technique fell out of favour, though it has continued to influence artists throughout the ages.

I still find Seurat’s works to be awe inspiring on a technical level, but the Impressionist styles he depicts is far from my current personal tastes. Not that that’s stopped me from seeking out his or others’ Pointillist works any time I’m in a major museum.

That’s why I like it.

The sum is often greater than the parts.

Additional reading:

A Sunday on La Grande Jatte page at Art Institute Chicago

John Hughes comments on the museum scene in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, which features Seurat’s most famous work: Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (2 min YouTube clip)

Previously, on Why I Like It:

Nov — Lay Down Dream (2007), Jessica Anne Schwartz

Oct — Family of Robot (1986), Nam June Paik

Sep — H2O (2005), Vassilis Karakatsanis

Aug — Composition C (No.III) with Red, Yellow and Blue (1935), Piet Mondrian