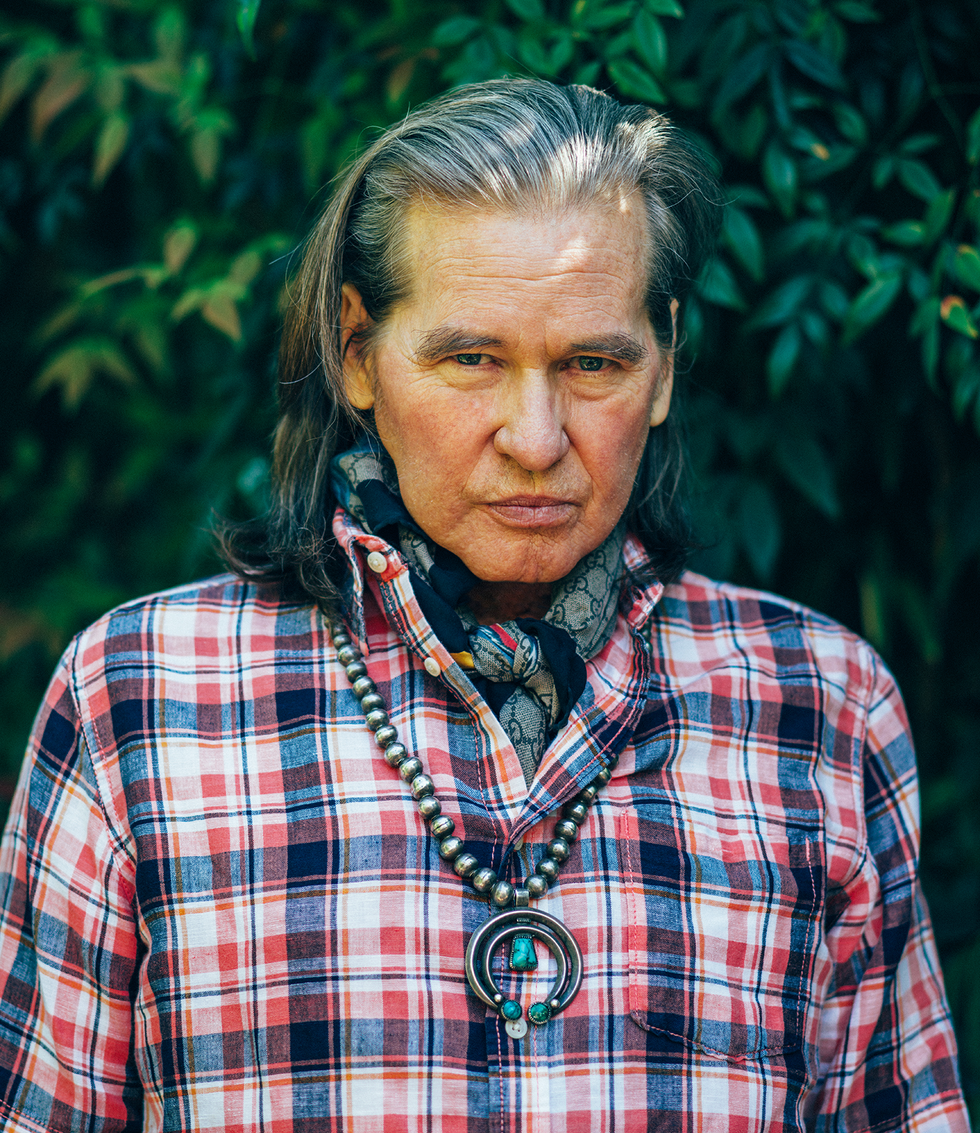

SOME YEARS AGO, Val Kilmer began selling his original artwork on the Internet. Kilmer has been making art for a long time. He takes photographs and creates scrapbook-style media collages with atmospheric abstract paintings resembling blooms of underwater lava. His neon sculpture of a dyspeptic-looking Mahatma Gandhi hung for a while in the restaurant of a fancy hotel in South Beach, and he once cast a tumbleweed in 22-karat gold.

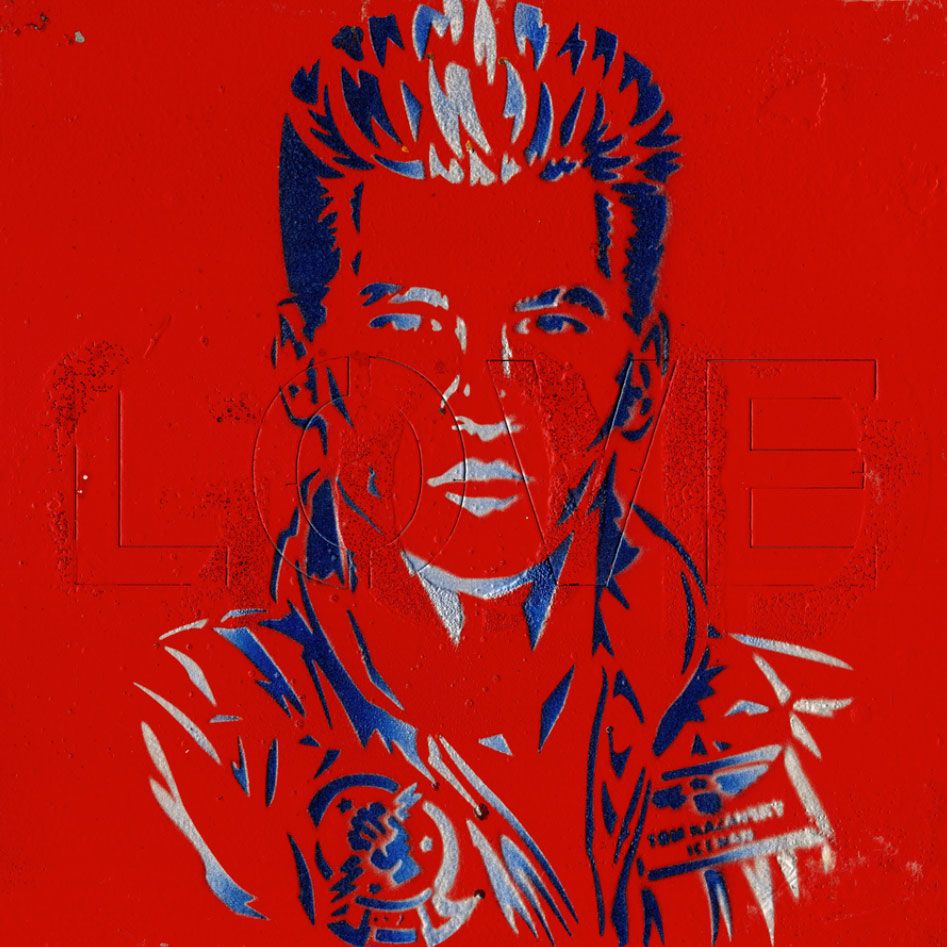

But the project he’s become most famous for is an ongoing series of quasi-self-portraits—Warholian pop-art images of Kilmer in character as Batman or Doc Holliday or Jim Morrison, rendered using stencils and brightly colored enamel paint on 12-inch-by-12-inch squares of reclaimed steel. Sometimes he’ll superimpose a stenciled word like love on the image, or a variation of a quote from one of his movies, such as chicks dig the car. His website didn’t have any Doc Holliday paintings at press time, but for a fan-friendly $150, you could still acquire a portrait of Kilmer as Tom “Iceman” Kazansky—Tom Cruise’s nemesis and beach-volleyball rival in Top Gun—in a range of colors, from neon green to red and blue to eerie red-on-black.

These are not the most technically complex or conceptually weighty paintings. They are not even technically complex or conceptually weighty by the standards of other paintings by Val Kilmer. But there’s an additional layer of meaning to them, because they’re portraits of Val Kilmer by Val Kilmer.

The pictures feel like a sincere effort on his part to use the tools at his disposal

to make sense of his own relationship to a postmodern character called “Val Kilmer,” who is less a person than a collection of symbolic echoes, and who casts a long shadow over the real Val Kilmer’s life despite existing solely in the media landscape and the public’s mind. There is nothing inherently interesting about a piece of steel with a stenciled image of Val Kilmer as Batman on it, but a piece of steel on which Val Kilmer himself has painted a stenciled image of Val Kilmer as Batman as part of a project involving the painting of dozens of Val Kilmer-as-Batman images becomes an act of introspection, a commentary, a reflection on reflections and the indelibility of iconicity.

One afternoon in early March, I discussed all of this with Val Kilmer over the phone. “Yes,” he said. “By repainting the exact same thing using a stencil, it was a way of contemplating the subject while being very strict with what I was inviting myself to do.”

I asked him if the paintings were a way for him to work through the feeling of being known without being known, to help process the weirdness that comes with everyone looking at you and seeing Iceman or the Lizard King. “It’s not so much me thinking about myself,” he said. “It’s more about the icon. The icon of the warrior. Or the gunslinger—that black-and-white justice that’s part of American history. That’s Doc Holliday. And then Jim Morrison is an iconic rock ’n’ roller, a poet.

“I also found there was a surprising number of fans who wanted original paintings,” he continued, as if to puncture the self-importance of talking about this work in this way. “I sold an embarrassing number of them.”

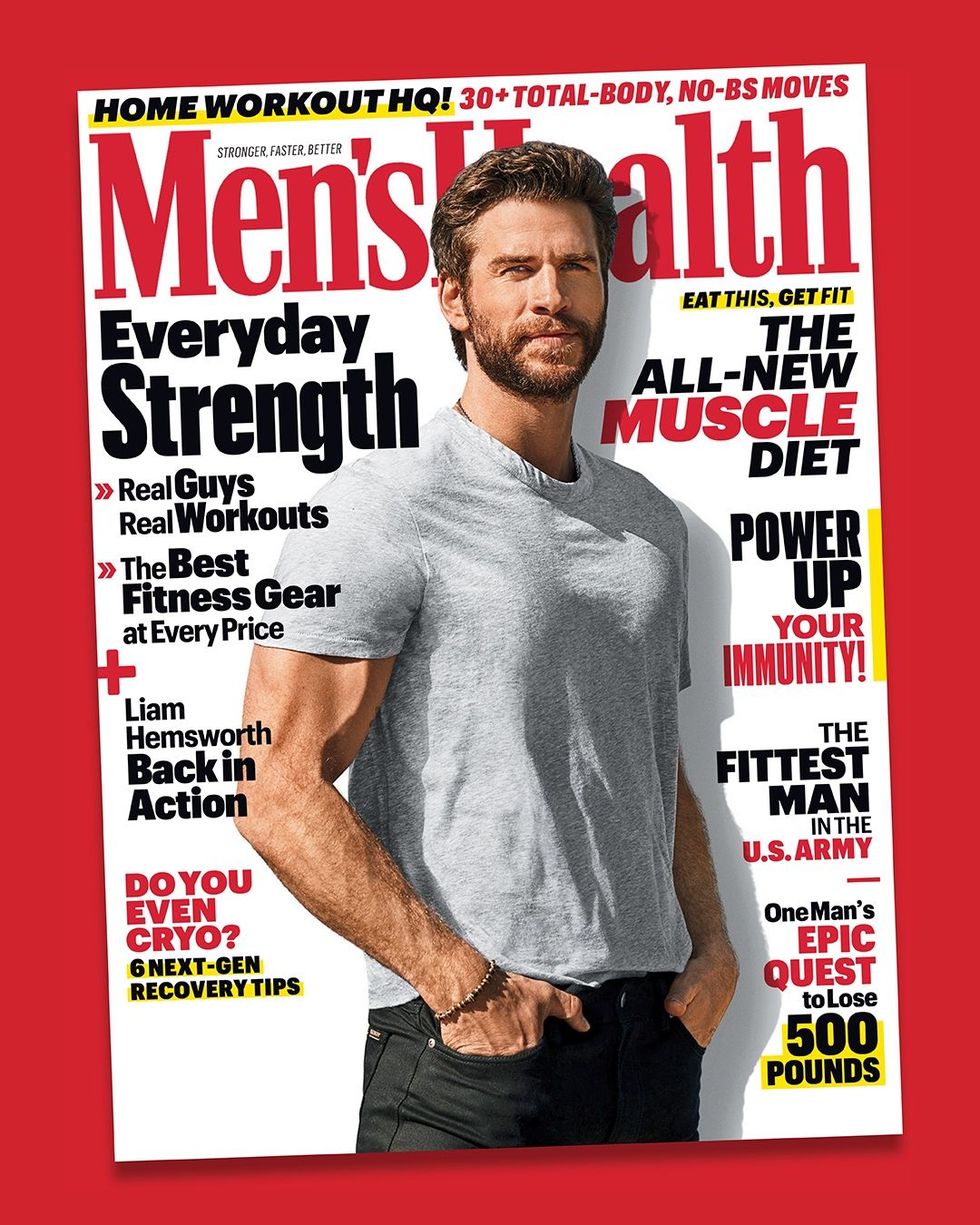

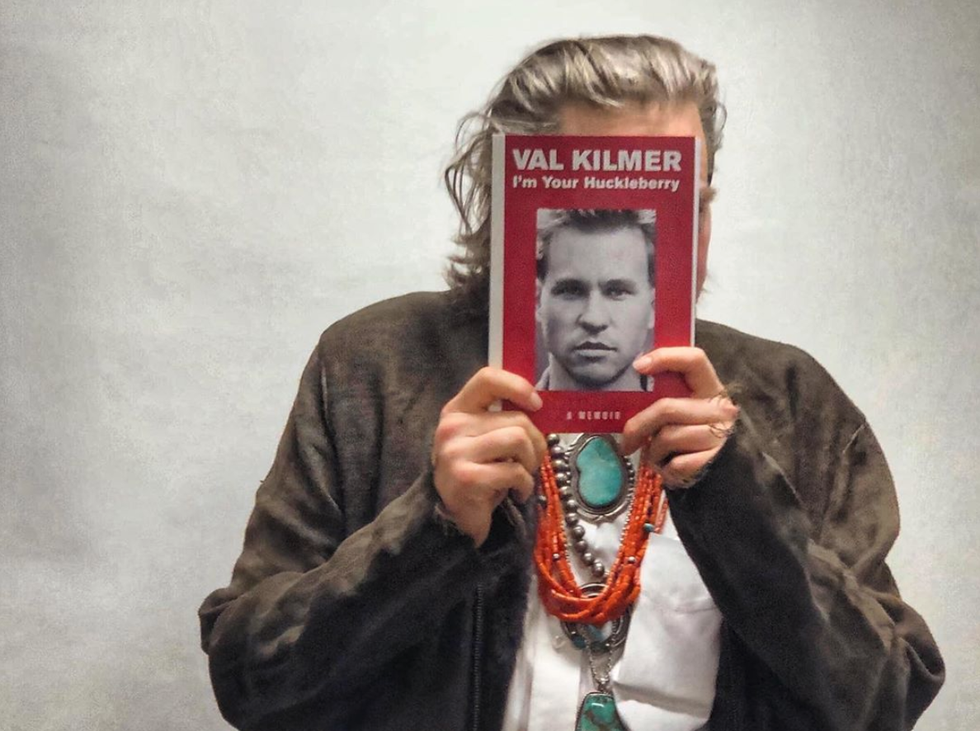

I think he laughed when he said this; I’m not positive. It was a strange conversation, because there was no way for it not to be. Kilmer, now 60, was diagnosed with throat cancer in 2015. In the opening pages of his new memoir, I’m Your Huckleberry, (Simon & Schuster, April 21, 2020) he has lost his New Mexico home as a result of the 2008 financial crisis and finds himself convalescing at an ex-girlfriend’s place. This is a book of absurd juxtapositions; the home happens to be an Italian Renaissance–style palazzo in Malibu overlooking the ocean, because the ex-girlfriend happens to be Cher. He is there when his condition takes a fateful turn.

“Cher dipped out for afternoon errands,” he writes. “Night fell, and I fell asleep. Suddenly I awoke vomiting blood that covered the bed like a scene out of The Godfather. I prayed immediately, then called 911.” Eventually he endures two tracheotomies. “The cancer miraculously healed much faster than any of the doctors predicted,” he writes, but adds, “It has taken time, and taken a toll. . . . Speaking, once my joy and lifeblood, has become an hourly struggle.” He describes his new voice as sounding “like Marlon Brando after a couple of bottles of tequila. It isn’t a frog in my throat. More like a buffalo.”

Kilmer and I both live in Los Angeles. COVID-19 had not yet rendered in-person interactions verboten, so I suggested we could talk in person, but he wanted to speak over the phone, through an interpreter—his high school friend and business partner, Brad Koepenick. I would ask a question, I’d hear some indistinct buffalo growls on the other end of the line, and then Koepenick would repeat Kilmer’s response to me in his own voice. We spoke to each other this way for about an hour.

At first there were a few people speaking in the room, and I asked Koepenick if he could identify himself. “I’m Brad Koepenick,” he said. After that, I heard Kilmer speaking—rarrrggh rarrrggh rarrrggh—and then, speaking for Kilmer, Koepenick said, “I am Spartacus.” For all his responses, for clarity, when Koepenick is speaking Kilmer’s words, I’ve attributed them to Kilmer, and I’ve attributed Koepenick’s occasional comments to Koepenick.

To understand Val Kilmer, in all his incarnations, it’s important to recognize that he has been a Christian Scientist since the age of seven or eight. Founded in 1879 by the author Mary Baker Eddy, Christian Science is a form of metaphysical Christianity whose adherents believe, among other things, that physical illness and infirmity result from mental misconception or “negative thinking.” All of Kilmer’s answers to questions regarding physical matters reflect these beliefs—as he writes in his memoir, his physical difficulties have led him deeper into spiritual practice: “When one sense weakens, another grows strong. I have more time to play in the metaphysical forests.”

It says something important about Val Kilmer’s mind, however, that the only historical figure who seems to loom as large in his personal pantheon as Mary Baker Eddy is Mark Twain. Twain was a contemporary of Eddy’s, and while he spoke approvingly of Christian Science’s core principles on occasion, he saw its founder as a charlatan.

In 2012, Kilmer began portraying Twain—whom he views as “the first media-literacy educator”—in a one-man stage show, Citizen Twain, and has spent years working on the script for a movie depicting a fictional meeting between Twain and Eddy, which he still hopes to direct. “Twain is the antagonist in the story,” Kilmer says. “Mary Baker Eddy is the protagonist. Mark Twain can’t help his pride and ego, his madness.”

I asked if this was what Kilmer related to about Twain as a character.

“His madness?” Kilmer asked, and then Koepenick, the interpreter, laughed.

Sure, I said. His pride, his ego, his madness. “Yeah,” Kilmer said. “We all have pride to work through.”

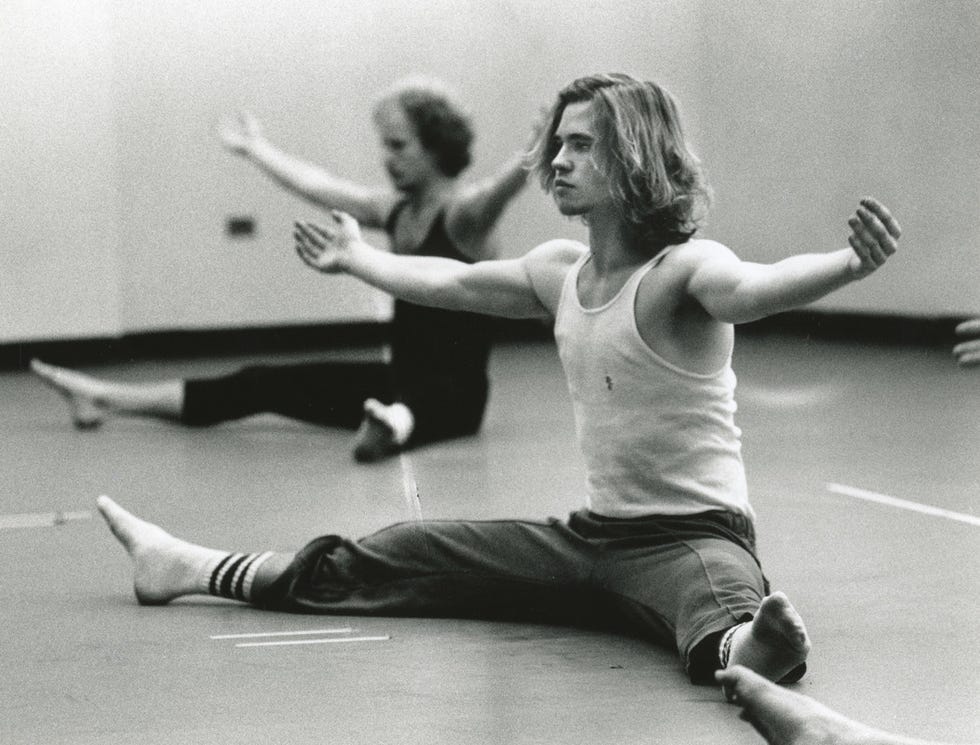

I WANTED TO TALK to Val Kilmer about pride. When he was young, he was beautiful, and moved through the world with the ease of someone beautiful, from school plays to Juilliard to the movies, such as 1984’s Top Secret!, which instantly made him a movie star for playing a rock star. One year later, with Real Genius, he was already a hyper-opinionated pain in the ass on set—he admits as much in his book—and a year after that came Top Gun, and with it great fortune.

Kilmer was a stage-trained actor with grand aspirations—he writes with chagrin about turning down the lead in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet due to the script’s sexual content and cops to badgering Stanley Kubrick for a meeting he never got. But by the mid-’90s, he’d become an A-list leading man who was reportedly receiving $6 million per picture, which was a different kind of grand.

His movie career hit its zenith in the first five years of the ’90s, when he played Jim Morrison in Oliver Stone’s The Doors, Elvis’s ghost in True Romance, the gunfighter Doc Holliday in Tombstone, Robert De Niro’s demolitions-expert partner in Michael Mann’s bank-heist epic Heat, and Batman in Joel Schumacher’s goofy, garish Batman Forever. Those last two came out in 1995, and after that the going got weird. Whether Kilmer walked away or was released from his contractual obligation to play Batman again due to difficult behavior is unclear. His next projects were the film version of the 1960s TV series The Saint—in which he disappears behind a series of increasingly ludicrous wigs and glasses like somebody who really, really wants you to know he went to Juilliard—and a remake of The Island of Dr. Moreau, which became one of the decade’s most infamously cursed productions.

In the pages of Huckleberry, Kilmer is equivocal about his reputation as a temperamental collaborator (“In an unflinching attempt to empower directors, actors, and other collaborators to honor the truth and essence of each project . . . I had been deemed difficult and alienated the head of every major studio”), but he talks straight about much of the work that followed (“I have here described myself as a man with lofty goals, and I have a solid two decades’ worth of work that I’d describe as less than lofty”).

There are true gems in Kilmer’s post-Moreau filmography, like the David Mamet human-trafficking thriller Spartan, Shane Black’s manically inventive Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, and MacGruber, in which Kilmer plays a Bond-style villain named Dieter Von Cunth. His hazy-eyed performance as the doomed ’70s porn star John Holmes in 2003’s Wonderland is a riff on his Morrison but funnier and sadder, the Lizard King as lost soul. But for all intents and purposes, Batman was his farewell to franchise-hero parts. Having grown up watching Kilmer in blockbuster movies and then appreciating his work in smaller films, I never thought of him as a cautionary tale about hubris or ego, but Huckleberry points in that direction. His last thought on turning down Lynch is a poignant plea: “Maybe it’s not too late,” he writes. “Maybe one day we can finally work together. A character who lives up on Mulholland and doesn’t speak much? David, I am so sorry I never explained myself.”

We never got around to talking about Lynch, though, because we started talking about death, which led us to God, which left no time for much else. Shortly after a 17-year-old Kilmer left his home in L. A. for Juilliard, his younger brother, Wesley, suffered an epileptic seizure in the family’s Jacuzzi and died on the way to the hospital. I asked Kilmer about how he managed to avoid letting this loss define him.

“You have to not see it as a loss,” Kilmer told me. He writes in the book that he’s heard Wesley’s voice on occasion, admonishing him from beyond the grave: “No one wants to see or hear a handsome, successful, talented writer-actor-director who gets the most impossible-to-get girls in the world complain about a damn thing.”

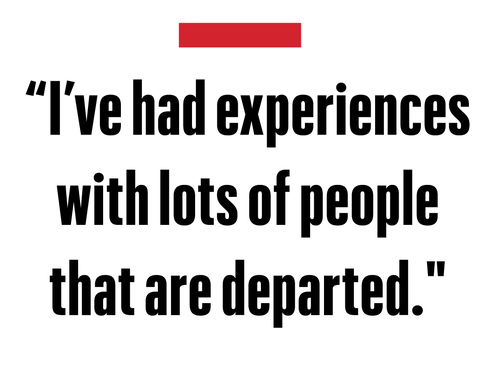

“I’ve had experiences with lots of people that are departed,” Kilmer said on the phone. “For instance, my mother passed on recently, and a few days after, I was aware of her—you could call it her spirit. And she wanted me to be happy, because she was having a reunion with her son Wesley and the love of her life, Bill, her second husband. And they were just all so happy. It was a great release of a burden—because my mom, I felt, wasn’t so happy sometimes, here on earth.”

Kilmer’s access to the unexplained and extrasensory is a major through line in his book. At 24, in New Mexico, he encounters a black-robed figure in a vision, whom he recognizes as the Angel of Death’s opposite, the Angel of Life, who pulls out Kilmer’s heart and gives him a bigger one. At a comic-book convention, across a table where he’s signing Batman stuff for Batman fans, Kilmer meets a Native American fan who asks him, “What is acting?”—a question that unlocks the meaning of a recurring dream Kilmer’s father had about dying in battle with another Native American man on the frontier. On a backpacking trip in Kenya with his then wife, Joanne Whalley, Kilmer steps outside his tent, and there’s a nine-foot-long monitor lizard sitting there.

I asked Kilmer if he’s thought much about why these messengers and symbols appeared to him, if he believes they were put in his path for a reason, and if all of us could interact with the metaphysical world in this way if we paid closer attention to its manifestations.

“Yes,” Kilmer said. “I do think it has to do with paying attention. And also asking for [those signs]. I’ve always had a very strong relationship with wild animals, especially animals like the kudu, which are very hard to spot, or the badger, or the black leopard, or the black panther.”

Kilmer said something else after this, and Koepenick, confused, repeated it back to Kilmer as a question: “Kanye forever?” Kilmer said the words again, clarifying, and Koepenick, to me, said, “Wakanda forever.”

“My translator’s higher than hell,” Kilmer said.

“I’ve got to lay off the ganja, you’re right,” Koepenick said.

Is it possible, I asked, to summon these things into your life? To seek these encounters with animals and other spiritual beings?

“I think so, yeah,” Kilmer said. “I mean, I’ve never been interested in hunting. But at the same time—this is a true story that sounds unreal, but I’ve been back to the same spot in South Africa, a hunters’ spot that you have to rent. It’s very expensive because all the animals there are very mature, so their horns are very big. And I’m not a hunter, but I rent the whole area so I can have as wild an experience as possible with very big game. And the most vindictive animal out there is the Cape buffalo. The Cape buffalo has a phenomenal memory, much better than the famed elephant.

“And I’ve been to the same spot three times. And the second time I went there, [a Cape buffalo] smelled me, even though I was the third in a line of humans, and he trotted over until he was right in front of me. And then he stared at me for half an hour, as if to say, ‘Your move—I’m ready.’ And then the third time I went, he did the exact same thing. Except it was more extreme because the wind was blowing harder. And he was very specifically putting his nose in the air, as if he was displaying—I’m smelling, I’m smelling. But this time it was almost like a playful kind of dance over to me. And I had the same guides [as before], and the guides were freaking out. They were babbling in their native tongue: He knows you, he knows you. He’s coming to say hello. They were freaking. And I was like, ‘I know.’

“But that happens a lot,” Kilmer said. “Like honey badgers, you know? Impossible to see in the daytime. I’ve seen them in both the daytime and the nighttime.”

YOU'VE PLAYED ALL these heroes over the course of your career, I said to Kilmer. There’s a tendency in our culture to frame illness in heroic terms, as a fight for life or an occasion for bravery, particularly when we’re talking about someone we think of as heroic in another context. We make shirts about kicking cancer’s ass and write headlines like "val kilmer battles cancer." For someone who’s been through it, is the idea of a brave battle with cancer the wrong way to think about it?

Kilmer answered without really answering. He talked about mental attitude. “It’s half of the healing—making sure the mind is free, in the morning, of limitations.”

Later, at the end of the call, Kilmer gave me his email address in case I had any follow-up questions. After a week or so, I wrote him an email in which I asked him a few fact-checking questions about the timing of his diagnosis and his recovery, and whether it was difficult to balance his Christian Scientist beliefs with traditional medicine. He didn’t answer, though this might be because I also asked him, very gently, if he had any regrets about being a jerk on movie sets.

That day on the phone, I let the conversation go where it wanted to, reluctant to steer it back to Moreau’s island. I asked Kilmer if it was hard to get to that place of being free and clear, if it was something he had to cultivate. Kilmer said no, that his spiritual practice had been part of his life since childhood. Then he asked, “Alex, do you believe in God?”

I stammered something about being a skeptic, because suddenly I felt guilty telling Christian Science Batman that God does not play a role in my life.

“The infinite,” Kilmer said. “Have you had a sense of the infinite?”

I confirmed to Val Kilmer that I have had a sense of the infinite and stammered again about psychedelics and the notion that something must exist outside the boundaries of our consciousness.

“And I think the physical science is catching up with that,” he said. I asked Kilmer if having cancer tested his faith, if there were moments when he wanted to give up hope. He quoted what turned out to be a line from the Gospel According to Mark, about faith in the face of doubt, about doubt as a specific crucible for faith: “Lord, I believe. Help thou mine unbelief.”

What you can tell about Kilmer even throughout an odd and stilted back-and-forth is that he’s been through something and emerged from it that much more certain of the one thing he believes most strongly, which is that mental attitude can have transformative effects. As an inveterate doubter, I wanted Kilmer to express doubt or regret or otherwise admit to a sense of powerlessness, which I suppose is contraindicated in a worldview based on the all-importance of mental attitude. It was the paintings conversation all over again—I wanted him to talk about the gulf between our heroic notion of the movie star and the actual flawed human behind it, but he couldn’t, or wouldn’t, see it in those terms.

So I asked him what the most surprising thing was about his illness. He paused for a minute and then said, “Well, something that was reaffirmed to me—on such a level, it was almost shocking—was a sense of universal love, a kind of power and a different sense of love. It was coming into my consciousness and my body while I was at the hospital.”

At one point, Kilmer said, one of his doctors saw him and became animated, even overjoyed. This specific doctor, he said, turned out to have been present during a moment when Kilmer almost slipped away. “He lost me for a while, and he was just so happy I was back. He wanted me to be happier. I was grateful, but I was not surprised.”

Why not?

“Because I don’t believe in death,” Kilmer said.

I asked him how he managed to shake a belief that defines life itself in a fundamental way for so many people on this planet. He spoke again about his little brother’s death, how even though he’d spent years by that point reading and thinking and praying on the Christian Scientist concept of death as an illusion, “having to live it out becomes quite a different proposition.”

Christian Scientists believe any malady can be overcome through mental effort, death included. “And this is what Mrs. Eddy meant when she talked about reinstating primitive Christianity. That’s how she thought Jesus was teaching—teaching others to heal themselves. And that’s what made him a dangerous man. Because he taught people how to be independent, and that’s always a very, very radical thing to do in society.”

I don’t know enough about science, much less about faith, to argue with Kilmer. And yet, sitting there on the phone, I realized I envied his ability to believe, his confidence in the face of cosmic uncertainty. I envied the security he derives from what he thinks he knows.

It’s extremely human, when faced with adversity, to fall into wallowing and selfishness and sadness and not wanting to go on, I said to Kilmer. How do you avoid surrendering to those feelings?

“Sometimes you have to be aggressive about finding a way to be courageous,” he said, “and not believing what your physical picture may be demanding you accept as real. Like if someone came into the room, and they were sleepwalking, and they were screaming that their feathers were on fire, what would you do?”

Well, you’re not supposed to wake a sleepwalker, I started to say, and then Kilmer interjected.

“You have to find a way to wake them up,” he said, “because they don’t have feathers, and so they’re not on fire.”