Modigliani on the Move

Girl in a Green Blouse, 1917, oil on canvas, 32 x 18 1/2 in. (81.3 x 46 cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Chester Dale Collection (1963.10.45) [1]

January 24, 2023

An Analysis of Modigliani’s Interwar Market

David M. Challis

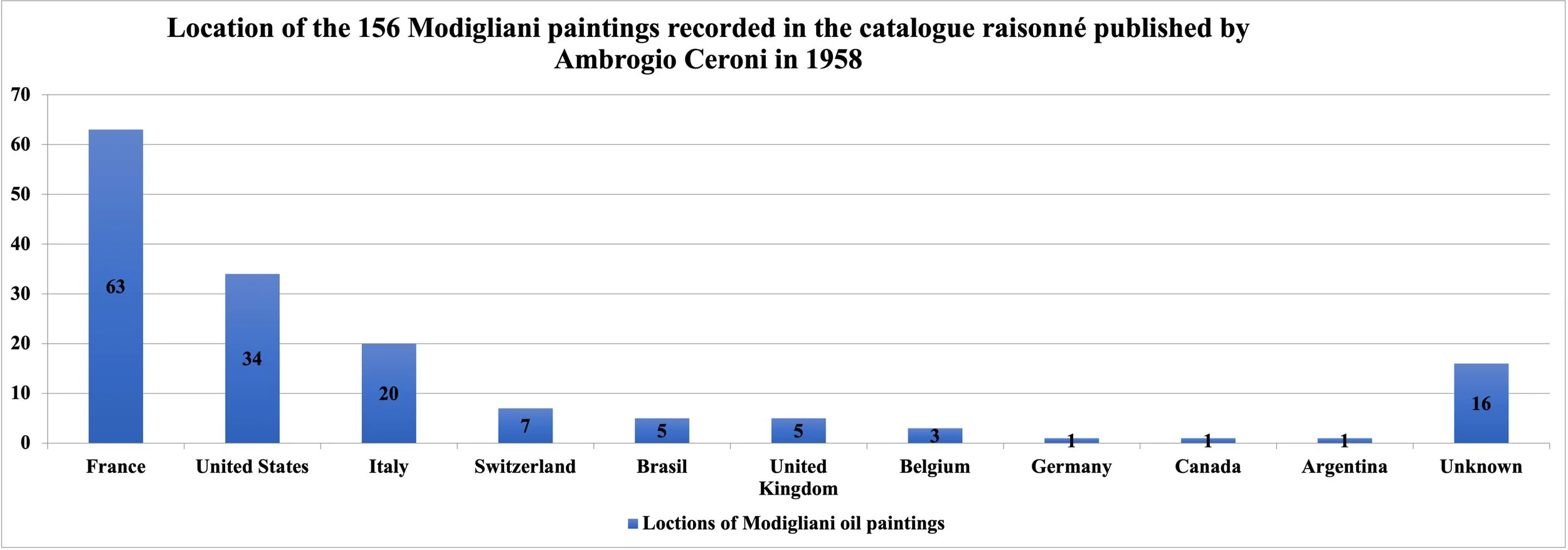

Analysing the geographical location of the 156 oil paintings recorded by Ambrogio Ceroni in his 1958 catalogue raisonné gives unexpected insights into the movement and increasingly favourable reception of Modigliani’s oeuvre in the first half of the twentieth century. While Ceroni’s work has been critiqued for its inaccuracies and omissions, the paintings recorded in the catalogue provide a solid case study for understanding where the vast majority of Modigliani’s work was located in 1958. The catalogue shows that in the thirty-eight-year period since the artist’s death in 1920, more than half of his recorded oil paintings had departed from their point of origin in France. These paintings were now located in art collections across a remarkably diverse range of countries, including the United States of America, Italy, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Germany, Canada, Brazil, and Argentina. (Figure 1)

(Figure 1) Location of the 156 paintings recorded in the catalogue raisonné published by Ambrogio Ceroni in 1958. Source: Author.

This simple analysis provides additional evidence of the growing international interest in the cohort of artists working in and around Paris in the early twentieth century. Paintings and sculptures by Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Pablo Picasso and Chaim Soutine, among many others, experienced a similar pattern of international dispersion. [2]

To the extent that the causes of this large-scale translocation of modern artworks have been examined to date, they have typically been positioned within the context of an increasingly favourable critical and commercial reception of the modernist artistic style. The momentum for this growing popularity was predominantly fuelled by a small group of entrepreneurial Paris-based art dealers. They promoted their respective artists through ground-breaking exhibitions in Paris, across Europe and abroad, with several taking the opportunity to expand their operations internationally. At the same time, the favourable taxation treatment in France and in the importing countries provided significant financial incentive for art dealers and collectors to favour contemporary art in preference to older artworks. The large-scale human migration of artists, art critics, and collectors away from Europe that occurred in the first half of the twentieth century has also been cited as an important modality for the translocation of modern art. But broader political and economic themes were also in play.

For one thing, the supply of modern art that became available on the international market was heavily influenced by a series of economic crises experienced in France and across Europe in the aftermath of the First World War. Rapidly escalating inflation and the concurrent devaluation of the French franc resulted in devastating economic consequences and an extensive flight of private capital away from France during the 1920s. This was followed by the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression in the early 1930s which led to a further dramatic fall in French private wealth. These circumstances resulted in a widespread liquidation of private assets. The transportable, liquid, and increasingly valuable nature of modern artworks meant that they became highly desirable hedges against inflation, currency devaluation, and wealth destruction. Of course, to extract their stored value, French collectors were eventually required to monetise their collections by selling the works in the international art market.

The dramatic collapse in the value of the franc during the 1920s also had significant consequences for art collectors located outside Europe. In essence, the increased purchasing power of currencies that had maintained their value against gold, and therefore against the franc, immunised international collectors against the worst of the price inflation in France. As shown in Figure 2 (below), the United States dollar, British pound, Australian pound, Japanese yen, and Argentinian peso, all increased in value by a multiple of seven against the franc in the mid 1920s before stabilising at a multiple of four for most of the interwar period. This gave international art collectors a substantial comparative advantage against French collectors, and it was during this period of elevated purchasing power that many of the international collections of modern art were assembled.

(Figure 2) Appreciation of the United States dollar, British pound, Australian pound, Japanese yen, and Argentinian peso against the French franc 1916 – 1940. Source: Author using Author using data from: FRASER®, Federal Reserve Archives, Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis. (Accessed 15 September 2018).

Understanding the causes of this international translocation of modern art is important because it had the effect of elevating the artists working in and around Paris in the early twentieth century into a pre-eminent position in what became the dominant EuroAmerican account of the evolution of modern art. For many influential critics and writers located outside Europe, their first opportunity to scrutinise modern artworks first-hand occurred when they visited newly acquired paintings and sculptures in private collections or at local art museums. This resulted in a wave of exhibition catalogues and other scholarly literature that significantly elevated the critical status of modern art across the globe. For Modigliani, this commenced with Roger Fry’s journal article “Line as a Means of Expression in Modern Art” in The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs in February 1919. [3] A more formal analysis was given to Modigliani’s oeuvre by the prominent Philadelphia-based art collector Albert C. Barnes in his 1925 book The Art in Painting. Like Fry, Barnes believed it was Modigliani’s use of line that differentiated his style:

“A basic feature of Modigliani’s form is a very graceful, clean-cut, and marvellously effective line, which not only clearly defines contours, but is the major factor in imparting an adequate solidity to the volume enclosed between the contours.” [4]

By 1925 Barnes had become convinced that Modigliani’s elongated, oval faces and long slender necks were influenced by African figurative sculptures, positioning him in direct lineage with other important modern artists, such as Picasso. He expressed this view in room 22 of the Barnes Foundation gallery in Merion, Pennsylvania, by positioning two of his Modigliani portraits: Madame Hanka Zborowska and Jeanne Hebuterne, laterally outside two portraits by Picasso that were in turn positioned outside a cabinet of African sculptural objects. (Figure 3)

(Figure 3) Room 22, South wall, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

Perhaps of greater importance, in terms of contributing to the critical reception of the Paris-based modern artists, such as Modigliani, was that many of the substantial international collections assembled in the first half of the twentieth century were either gifted or bequeathed to major public museums within a generation. Examples of this occurring are plentiful, including: the gift of twenty-two modern paintings from Samuel Courtauld to the Tate Gallery in London in 1924; the Lillie P. Bliss bequest of one hundred and fifty modern paintings to the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1931; and Assis Chateaubriand’s patronage of the modern art collection at the Museum of Art São Paulo in the late 1940s and 1950s. For many museum patrons, viewing these artworks represented their formative experience of modern art.

Endnotes

A note from the Modigliani Initiative database: This painting belonged to Dr. Marcel Norero of Paris who sold it, along with 100 works from his collection (including one other Modigliani), at a Drouot auction in February 1927 for 28,000 francs [the equivalent of US$1,098]. The buyer was the art dealer Etienne Bignou of Paris who was bidding on behalf of the U.S. collector Chester Dale. Dale went on to own a record sixteen paintings by the artist, most of which are now at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Analogous to this case study is the archival inventory kept at the foundry owned by Adrien Hébrard, who was given the initial contract to posthumously cast Edgar Degas’ sculptures. This inventory provides a similar example of the global nature of the movement of Modernist artworks produced by Paris-based artists in the early twentieth century. The Hébrard inventory recorded each of the original buyers and their locations for the 566 sculptures cast by the foundry between 1918 and 1936. Of the 566 sculptures, only 145 (25%), were sold to French buyers. For the remaining sculptures, 120 (21%) were sold to continental European collectors and 301 (54%), were sold to collectors in America, Britain, and Japan. However, this somewhat under-represents the movement of sculptures out of France because many of the French buyers of Degas’ sculptures were commercial art dealers, such as Berthe Weill, Hermann d’Oelsnitz and the Bernheim-Jeune family. Given the growing international market for French art, it is reasonable to assume that many of these sculptures were subsequently sold to international collectors. Joseph S. Czestochowski and Anne Pingeot, Degas Sculptures: Catalogue Raisonné of the Bronzes (New York and Memphis International Arts: Torch Press, 2002), 271–72.

Roger Fry, ‘Line as a Means of Expression in Modern Art’, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 34, 191 (1919): 62–9.

Albert Barnes, The Art in Painting (Merion Station: The Barnes Foundation Press, 1925), 376.

References

Ambrogio Ceroni, Amedeo Modigliani peintre (Milan: Milione, 1958).

David M. Challis, Foreign Currency Volatility and the Market for French Modernist Art (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2021),

David Challis, Archival Currency Converter 1916–1940,

About the author

Dr. David Challis is a postdoctoral researcher in the Art History program at the University of Melbourne. His ongoing research interests include exploring the historical underpinnings, structure, operation, and future developments of the international art market. His first monograph, titled Foreign Currency Volatility and the Market for French Modernist Art was published by Brill in 2021 and recently reviewed in the Journal for Cultural Economics in December 2022. His research distinctions include the 2020 Paul Mellon Centre Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. David returned to full-time study at the University of Melbourne in 2013 after a successful twenty-five-year career in the Financial Markets Industry based in Australia and London.

The Modigliani Initiative