‘You Must Love What We Do.’ Malangatana: Mozambique Modern

An upcoming exhibition will shine a light on the development of the Mozambican painter, poet, and revered national hero, who worked to break down Western stereotypes of the African population

Richard Gray / MutualArt

May 08, 2020

An upcoming exhibition will shine a light on the development of the Mozambican painter, poet, and revered national hero, who worked to break down Western stereotypes of the African population.

Malangatana, Esperando da Paz, 1995. Sold at Sotheby's London for 16,250 GBP, April 02, 2019. Courtesy Sotheby's

“Malangatana: Mozambique Modern” is poised to open this summer at the Art Institute of Chicago. The exhibition, hosted in association with the Foundation Malangatana Valente Ngwenya (FMVN) and Momo Gallery, will be worth a visit because it is the first opportunity since Malangatana’s death in 2011 to see a substantial collection of his work outside his birthplace, Mozambique. Remarkably, it will also be the first solo exhibition at the Institute by a “modern” artist born in Africa. The curators deserve credit for tackling this situation.

Malangatana Valente Ngwenya (1936-2011) chose to be known by his first name. The Chicago exhibition will present him as he wished to position himself, as a Mozambican/southern African artist with “things to say in the world”. Unlike artists who resist attempts to pin them down, Malangatana took pride in his roots. Born at the height of Portuguese colonialism, his early years were marked by the growth of the national liberation struggle and the coming of independence in 1975. This required a ten-year guerrilla war waged by Frelimo, the movement which became (and remains) Mozambique’s ruling party. Malangatana supported it by participating in clandestine political activity, for which he was imprisoned by the PIDE (secret police). After gaining independence, he and the Mozambican people were subjected to sixteen years of further conflict between Frelimo and Renamo, which opposed Frelimo’s attempts to establish socialism. Peace, formalised by UN-brokered elections in 1994, finally brought a multi-party democracy, structural adjustment by Western financial institutions and an ongoing process of recovery, if not reconciliation.

Malangatana, 1989, portrait by Andrea Moore

Malangatana’s art is inseparable from these events. It draws on his personal experiences as they happened: his childhood in rural Matalana, where he learned about the longstanding cultural practices of the Ronga community; his youth as a migrant to cosmopolitan Maputo (Mozambique’s capital, then called Lourenço Marques), where after starting as a childminder, he was a ball-boy, barista and eventually the head-waiter in an élite club; and his adulthood as an individual dedicated to overcoming what he called the “cultural depersonalisation” of colonialism, both pre- and post-independence. To this he added a commitment to peace in the devastated territory of his birth. Beginning around 1980, he was becoming a roving cultural ambassador for Mozambique, ready to be an African voice, when called upon in global forums. His public persona had led him to be conceptualised in a number of ways, from an autodidactic genius with a direct line to the collective subconscious of humanity, to a militant artist of the people, to International Artist of Peace, a title awarded him by UNESCO in 2007.

Malangatana’s experiences gave him the credibility to challenge Eurocentric discourse in the art world. He believed in the “viability of dialogue between European and African plastic arts.” Today, his works offer insights into the continuing process of decolonization. The upcoming exhibition concentrates on his oeuvre from 1959 to 1975, which, as the FMVN/Momo press-release says, was “a period in which he embarked on daring formal experiments and painted the rapidly-changing world around him, inviting us to consider his artistic development as part of the rise of modern African art”. There is room here to examine three of the show’s forty works. They reflect significant aspects of his practice.

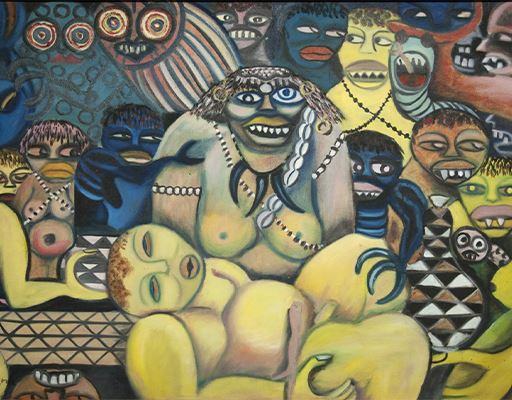

The Witch Doctor {sic}, or The Purification of the Child, 1962, oil on board, dimensions unstated, Oberlin College Libraries, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Lloyd H Ellis Jr

The Witch Doctor {sic}, or The Purification of the Child, 1962 demonstrates how Malangatana drew on specific, localized experiences from his rural childhood. A more appropriate term for the central figure is the Ronga “nyanga”. She is a healer, diviner and spirit medium, using her powers to cure the child in her arms, who has been bitten by the snake, visible on the top right. The other beaded figures are her assistants. The pot on the left holds a restorative medicament and the gourd on the right a vaccine against the snake’s poison. The blue figures are xipokho (maleficent spirit-monsters), visible only to the nyanga. They were probably sent by someone wishing the child ill, so she is fighting them off. The human figures behind are members of the child’s family and the local community. The owls have landed where there is rainwater, used by tinyanga (plural of nyanga) in remedies. According to Malangatana’s niece, Maria Alda Ngwenya, who is a qualified nyanga, the painting shows the importance of tinyanga to those without recourse to conventional Western medicine. The young Malangatana had first-hand experience of their capacities, because one of these “local Freuds”, as he called them, cured his mother of mental illness between 1947 and 1951.

Adam and Eve in front of the Cathedral at Lourenço Marques, 1960, oil on board, 121x121cm, FMVN

Adam and Eve in front of the Cathedral at Lourenço Marques, 1960 portrays the power of Roman Catholicism, which Malangatana encountered at mission school. Black Adam has been made to feel so guilty for desiring white Eve that he has cut off his leg. The alliance between the Catholic church and the Portuguese state helped enforce the colonial system, which insisted that the only way for Africans to become civilized was by assimilação, assimilation, i.e. abandoning their culture and heritage. In a newspaper interview about his debut solo exhibition from 1961, which included this painting, Malangatana said that “we can be civilized without giving up our own things.”

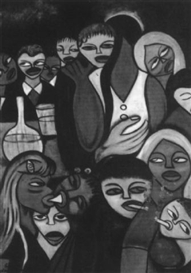

PIDE’s Punishment Room, 1965, black ink on paper, dimensions unstated, FMVN

PIDE’s Punishment Room, 1965, shows the consequences of his effrontery. The drawing is a self-portrait executed during the artist’s eighteen-month imprisonment from 1965 to 1966. He smuggled a series of related works out of gaol in a thermos flask brought by his wife, Gelita.

Malangatana would have been delighted by the Chicago show. As he said in an interview with me for the BBC film “Homelands:Malangatana” (1990, available on YouTube), “When I go to the West, I don’t say, ‘Look down, see how we’re suffering in Mozambique. Give us help, etcetera.’ I take something with me. I make my contribution. I’m a painter. For me, it’s sad when people in England, in America, say, ‘What kind of help do you need?’ What we need, really, is for people to understand that we are doing something, not only for Mozambique or southern Africa, but for the world. I want to say to people in the West that we want to share what we have with you. We love your culture – your art, your music – so you must love what we do. It’s part of your development”.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page