Why the 1876 election was the most divisive in U.S. history

Allegations of voter fraud and intimidation. A back-room deal. The Hayes-Tilden election was so controversial it spawned today’s vote counting process.

In 1876, the nation was still scarred and divided by the Civil War, which had ended a decade earlier. During the war’s aftermath, approximately four million enslaved people were freed, and a Republican-controlled Congress moved swiftly to protect their rights and restore the Confederacy to the Union. Southern states, meanwhile, chafed at their loss of political and social power.

Then came a presidential election that changed everything. Deemed the nation’s most divisive ever—until 2020, that is—the election of 1876 ended with an unusual compromise. And its weighty consequences still resound today. Here’s what you need to know.

A nation united, but still divided

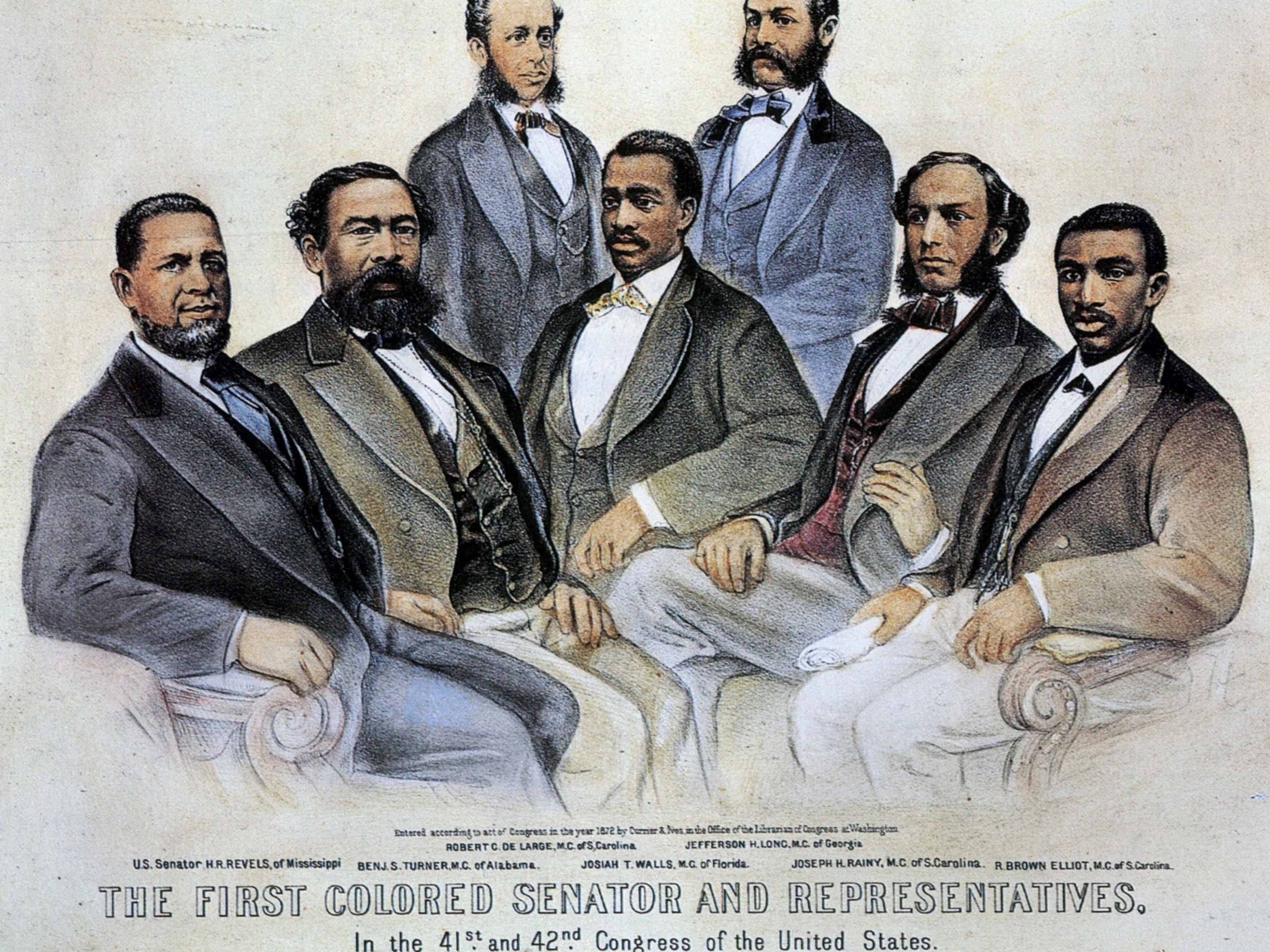

In the post-Civil War era known as Reconstruction, newly enfranchised Black voters overwhelmingly supported the Republican Party, whose members embraced President Abraham Lincoln and celebrated the Union’s Civil War victory. They registered to vote in large numbers and ran for and were elected to public office for the first time in American history. (Learn more about Reconstruction and the turbulent post-Civil War era.)

But white Southerners, who largely supported the Democratic Party, resented the federal government’s post-war policies. In an attempt to wrest back their power, they used intimidation and violence to disenfranchise Black voters.

Then, in the early 1870s, the Republican Party’s popularity took a hit due to an economic depression and political scandals. Between the Republicans’ tarnished reputation and white Southerners’ use of intimidation to suppress Republican votes, Democrats finally saw a path to electoral victory.

A bitter election

Although the stage was set for a dirty election, both 1876 candidates were seemingly above reproach. The Republican candidate, war hero and Ohio governor Rutherford B. Hayes, ran on a reform platform, promising to clean up the civil service and serve for only one term. His opponent, Democrat and New York governor Samuel J. Tilden, was known for challenging political corruption.

Their party operatives, however, staged a cutthroat campaign. Tilden’s opponents painted him as a diseased drunkard who planned to pay off the former Confederacy’s debts; Hayes’s enemies claimed he had stolen money from his brothers in arms during the war.

Election Day was even worse: Both parties participated in rampant fraud. Republican operatives stuffed ballot boxes, allowed repeat votes, and threw out Democratic ballots; Democrats physically intimidated Black voters in an attempt to keep them from the polls. (Voter fraud used to be rampant. Now it’s an anomaly.)

When the votes were counted, it appeared that Tilden had garnered 200,000 more votes than Hayes. But results were unclear in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, where both parties claimed victory—and alleged tampering. The states convened dueling electoral slates and sent conflicting returns to Congress.

Meanwhile, in Oregon, where Hayes had won the popular vote, the Democratic governor claimed one of the state’s three Republican electors was ineligible. As a result, the state also submitted competing certificates of the final electoral vote tally.

A total of 20 Electoral College votes—four from Florida, eight from Louisiana, seven from South Carolina, and one from Oregon—were contested. It would be up to Congress to sort out the mess.

Electoral mayhem

Democrats were furious about what they saw as the Republicans’ theft of their rightful victory in Southern states. Henry Watterson, a journalist and Democratic member of the Kentucky House of Representatives, used his platform to call for a “peaceful army of 100,000 men” to march on Washington unless Tilden was declared the winner.

Faced with fears of violence and a deadlock between the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives and the Republican-controlled Senate, Congress struggled to find a solution. The Constitution offered no clear guidance about how to deal with a contested electoral vote, and members suggested and bitterly rejected a variety of proposals.

Time was ticking. The presidential inauguration was scheduled for March 5, 1877, and legislators didn’t hit on a solution until late January. Finally, they decided to create a one-time commission consisting of an equal number of House and Senate lawmakers and five Supreme Court justices. Although multiple Republicans objected to the measure, it passed and outgoing President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Electoral Commission Act on January 29.

The Compromise of 1877

The electoral commission conducted a tribunal in the Supreme Court chamber in February 1877. Though the Democrats objected to the vote counts, they were outnumbered by their Republican colleagues by one and were consistently overruled. Each contested state was decided in favor of Hayes. Refusing to accept the results, the Democrats then filibustered in the House of Representatives.

It would take a backroom deal—and a momentous political compromise—to settle the election. During a series of secretive meetings, Southern Democratic lawmakers promised to call off the filibuster and concede the election in exchange for an end to Reconstruction.

Though the terms of the informal agreement remain unknown, it is thought to have included the withdrawal of all federal forces from the former Confederacy, increased federal funds for Southern states, the construction of a transcontinental railroad through the South, and the appointment of a Southern Democrat to Hayes’s cabinet.

In the wee hours of March 2, 1877, a mere three days before the scheduled inauguration, Congress completed the electoral vote count. Hayes won by a single electoral vote. Amid fear of assassination, he was sworn in during a secret ceremony the next day.

The controversial Compromise of 1877 was lauded by many at the time as a move that preserved the fragile Union and allowed the country to move forward as one. But it had disastrous consequences for Black Southerners. Without federal oversight, states created harsh “Jim Crow” laws that reestablished a brutal racial hierarchy in the South and effectively disenfranchised Black citizens. (Voter suppression has haunted America since it was founded.)

The Electoral Count Act

A decade after the Hayes-Tilden election was decided, Congress passed the Electoral Count Act of 1887 in an attempt to avoid further electoral chaos by providing a consistent system for the delivery of electoral votes.

The law, which still stands today, provides a mechanism by which Congress can determine whether electoral votes are legal: During the joint session of Congress held each election year on January 6, members can object to the votes of individual electors or states’ overall returns.

For an objection to be formally considered and voted upon, the law holds that it must be lodged by both a member of the House and the Senate. That has only happened three times in history—most recently in January 2021—and all objections failed.

The election’s legacy

The legacy of the turbulent 1876 election continues to roil American politics. During the 2020 presidential election, the Electoral Count Act received renewed scrutiny in light of Republican claims of voter fraud. On January 6, 2021, Congressional Republicans contested the results of Joe Biden’s win at the behest of incumbent Donald Trump—whose supporters later launched an armed assault on the U.S. Capitol Building.

Trump also claimed at the time that his Vice President Mike Pence, who presided over the count as president of the Senate, had the power to reject “fraudulently chosen” electors. But experts say the vice president in fact lacks that power—and a new bill before Congress seeks to reaffirm the vice president’s ceremonial role.

In September, the House passed the Presidential Election Reform Act, which would further raise the threshold for objections, but the Senate has yet to vote on it. Until then, it remains to be seen whether the election of 1876 will continue to haunt American politics.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

Environment

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

Travel

- Why this unlikely UK destination should be on your radarWhy this unlikely UK destination should be on your radar

- A slow journey around the islands of southern VietnamA slow journey around the islands of southern Vietnam

- Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?

- 5 of Uganda’s most magnificent national parks

- Paid Content

5 of Uganda’s most magnificent national parks