The Renaissance 'Prince of Painters' made a big impact in his short life

Peer to Michelangelo and Leonardo, Raphael produced many masterpieces before dying at age 37. His influence has only grown in the 500 years since his untimely death.

Renaissance Italy was a time of ruthlessness in politics and exquisite sensibility in art and culture, two extremes that shaped the life and art of Raffaello Sanzio, better known to the world today as Raphael. Younger than Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, whose influences he absorbed—and then matched—Raphael was a great Renaissance artist of harmony, proportion, and grace.

Although his masterpieces served the naked power politics of the day, and were commissioned by influential churchmen, bankers and a pope, they were also infused with tenderness and subtlety. The 16th-century painter and biographer Giorgio Vasari wrote in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects: “Most artists have hitherto displayed something of folly and savagery . . . In Raphael, on the other hand, the rarest gifts were combined with such grace, diligence, beauty, modesty and good character that they would have sufficed to cover the ugliest vice.”

By 1508 the young artist, already well-known in Florence for the brilliant Madonnas he had painted there, received a fateful summons from Pope Julius II: a commission to paint his Vatican apartments. The series of masterpieces that he created in these four staterooms, including “The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament,” and “The School of Athens,” forged Raphael’s fame as the “prince of painters.” His talent for clear storytelling through complex grouping, gesture, and color celebrated Catholic orthodoxy, pagan mythology, and humanist scholarship, linking all the tensions and glories of his age.

First steps of a master

Raphael was born in Urbino in northeastern Italy in 1483, the only surviving child of Magia di Battista Ciarla and Giovanni Santi, a painter in the court of the Duke of Urbino. Under the duke’s patronage, the city-state was a hub of cultural activity, and the duke could count the brilliant painter and mathematician Piero della Francesca among his courtiers.

Raphael’s parents both passed away when he was a child. His mother died in 1491. Before his father’s death in 1494, his father, whom Vasari described as an undistinguished painter, imparted the rudiments of painting to his son at an early age. The boy’s extraordinary talent was evident.

Raphael was sent to study in the workshop of Perugian artist Pietro Perugino when he was a boy. Perugino was admired for his mastery of perspective, a technique on display in his 1481 painting “Delivery of the Keys.” Perugino’s work depicts the moment Christ hands the keys of the kingdom of heaven to St. Peter. The carefully arranged scene takes place in a large square with the lines of perspective converging in the central doorway in the background.

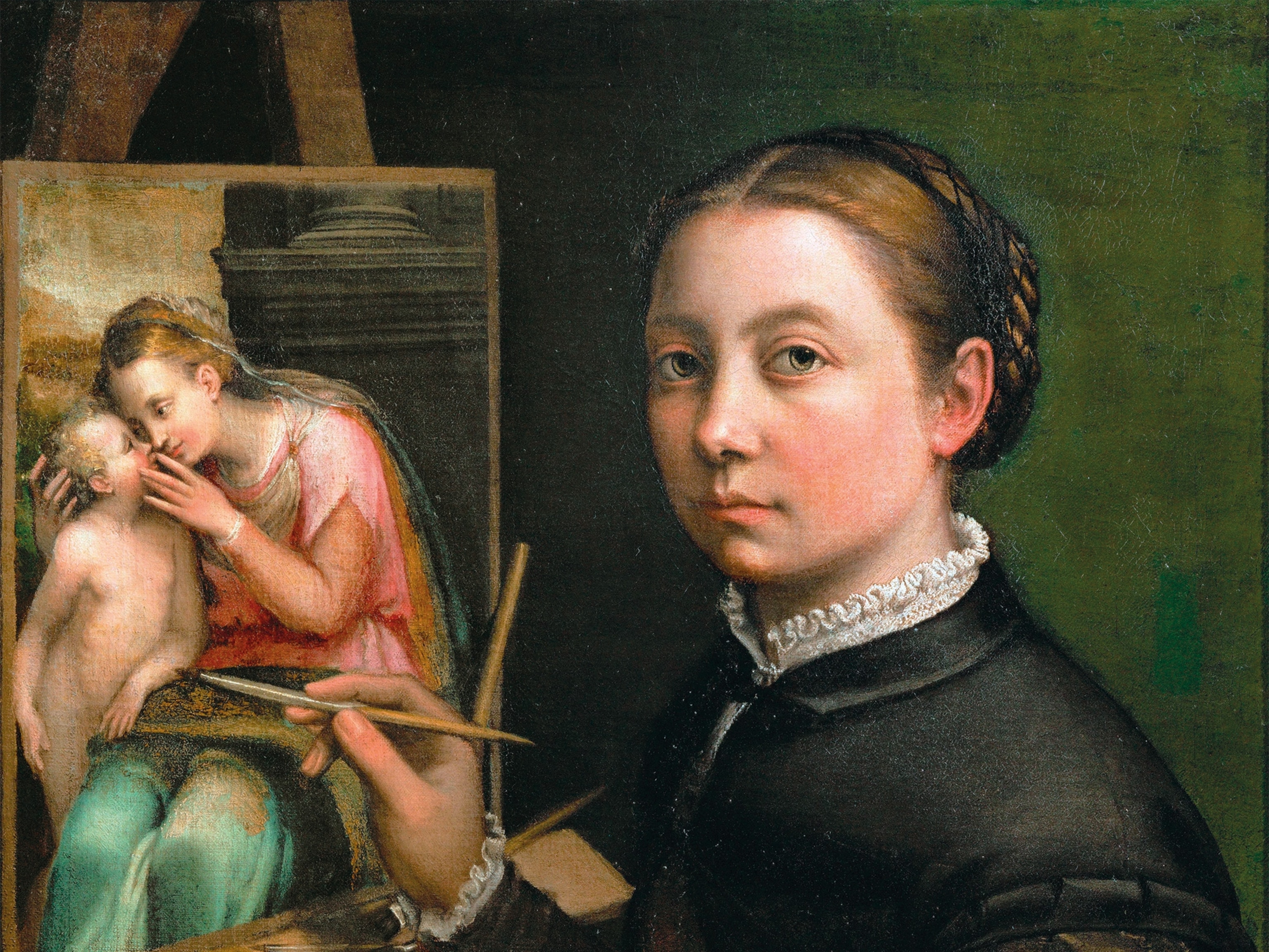

Unsurprisingly, Raphael’s early paintings bear the strong imprint of his teacher. The 1504 painting “The Marriage of the Virgin,” for a chapel of the Albizzini family in the church of San Francesco al Prato, in Città di Castello, shows clear similarities with the earlier painting by Perugino. It too takes place in a Renaissance square. Two groups in the foreground flank the central characters, the Virgin Mary and Joseph, who is placing a ring on her finger. Space and perspective are built up by the figures in the square behind, receding in size, and, as with Perugino’s painting, the lines of perspective converge on the doorway of the church. (This audacious artist shocked 17th-century Italy with her work.)

Behind the groom stand Mary’s other suitors who all carry sticks. Joseph also holds one, but his is blooming. Raphael’s work illustrates a popular legend. According to the story, Mary presented sticks to all her suitors, telling them that she would marry the one whose blossomed, a sign of divine favor.

Raphael was not merely content with perfecting the perspectival relations between the figures; he also used their positioning to create a complex harmony. There is nothing haphazard or accidental about their placement: Beauty, to Raphael, was about calculation and artifice, “making things not as Nature makes them, but as Nature should.”

Florentine flair

The next phase of Raphael’s life would be marked by building on all he had learned in Perugia and blending it with new influences to create his own distinctive visual style. Key to this process would be exposure to the great masters working at the time. Raphael traveled first to Siena and then to Florence, the epicenter of Renaissance painting. Vasari wrote that on arrival in Florence, Raphael “was no less delighted with the city than with the works of art there, which he thought divine, and he determined to live there for some time.”

The two principal talents who shaped Raphael during this crucial phase were Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, who were creating some of their best works in the early 1500s. Both men were older than Raphael (Leonardo by 31 years and Michelangelo only by eight), and Raphael adopted and modified their techniques. From Leonardo, he mimicked both Leonardo’s pyramid-shaped compositions and his use of sfumato, a technique that relies on soft, fine shading rather than harsh lines.

The Madonnas painted by Raphael in his Florentine period were influenced by Leonardo’s 1503 work “The Virgin and St. Anne,” which depicts a lamb held by the Christ Child as his mother Mary embraces him. The Virgin is, in turn, seated on the lap of her mother, St. Anne. The figures form a pyramid, and their complex interactions influenced several of Raphael’s Florentine Madonnas, which feature multiple figures, including “La Belle Jardinière” (“The Beautiful Gardener”). (Why Leonardo da Vinci’s brilliance endures, 500 years after his death.)

With Michelangelo, Raphael not only observed how accurate rendering of human anatomy could reveal the sublime, he also became engaged in one of art history’s greatest rivalries. Michelangelo did not care for Raphael at all; some art historians attribute his ill will stemming from losing a commission to the younger artist in 1508.

Michaelango's influence can be seen in Raphael’s 1507 work, “The Deposition,” which shows the lifeless body of Christ being borne to his tomb. The Virgin Mary, in blue veil, faints from the agony of her loss. The anatomy, weight, and positioning of the figures, especially the kneeling woman before the Virgin, are reminiscent of those in Michelangelo’s works such as the “Doni Tondo” and the unfinished “Battle of Cascina.”

Roman triumph

Raphael beat both Leonardo and Michelangelo to secure a commission from Pope Julius II to create frescoes at the Vatican. The young artist relocated to Rome and began work around 1508.

Michelangelo was working on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel during this time, and art historians believe that the two artists’ competitive relationship drove both their works to greater heights. Completed in 1511, Raphael’s four frescoes on the walls of the Stanza della Segnatura, the papal library, are among his finest works, especially “The School of Athens,” which many regard as his masterpiece. The work contains depictions of 50 philosophers, including Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Ptolemy, Euclid, Averroes, and Hypatia of Alexandria.

Art historians believe that Raphael used his contemporaries as inspiration for his figures. The central figure of Plato, who points to the sky, is modeled after Leonardo da Vinci. A lone, brooding figure sits in the foreground, his head resting on his hand. Many believe this bearded figure is Michelangelo. Raphael also placed himself in the portrait at the far right. He stands next to Zoroaster (who holds a celestial sphere) and Ptolemy who holds a globe. (See where Leonardo da Vinci still walks the streets.)

Renaissance Christians believed that the great humanist ideas of the past were completed and perfected by Christ, and the fresco Raphael painted directly across from “The School of Athens” displays that theme of theology. “The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament” acts as a mirror and counter-weight to philosophy, with similar composition and palette, but different focal points. The upper part of the painting is the kingdom of heaven centered on Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, and St. John the Baptist. Above them in a golden realm sits God the Father and the angels.

Below them on Earth, theologians and popes debate the miraculous properties of the Sacrament contained in the vessel on the altar. Echoing the composition of “The School Of Athens,” the groupings are complex and interrelated, but unlike the great philosophy painting, the theologians are not depicted inside a building, but outside in nature below a bright blue sky. (The painter behind 'Birth of Venus' invented a new kind of art.)

Raphael would continue to work at the Vatican by himself and with apprentices to create frescoes for other papal chambers. He also took on private commissions, including portraits, and architecture. Pope Julius’s banker, Agostino Chigi, commissioned Raphael’s design of his funerary chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo in 1513. After Pope Julius II’s death in 1513, his successor, Leo X, continued working closely with the talented Urbino painter. He appointed Raphael as director of the building works at St. Peter’s when Donato Bramante, the original architect, died in 1514. In 1515 the pope commissioned designs from Raphael for 10 massive tapestries that would hang in the Sistine Chapel. (This Renaissance warrior woman defied powerful popes.)

Love and Beauty

Earthly pleasures

Raphael spent the rest of his life in Rome. He founded his own studio and employed as many as 50 artists and pupils to work with him on his new commissions. He never married nor had children. Vasari wrote that Raphael might have been delaying marriage because he believed a future appointment as cardinal could be coming from the pope.

Despite this reasoning, Raphael did develop a reputation as a ladies’ man. Vasari wrote that “Raffaello was a very amorous person, delighting much in women,” including courtesans. According to tradition, Raphael’s great love was Margherita Luti, a baker’s daughter and almost certainly the model for Raphael’s beautiful portrait “La Fornarina,” painted in 1518-1519. He was also known for his intensely creative friendships, especially with the diplomat and scholar Baldassare Castiglione, the subject of one of Raphael’s most engaging portraits.

In 1517, rich and successful, Raphael bought the Palazzo Caprini in Rome, where he died on Good Friday, 1520. Vasari attributed Raphael’s death to sexual overindulgence, hinting at venereal disease, but the true cause of death is unknown. Raphael was laid to rest in the Pantheon. His epitaph reads: “Here lies Raphael. Living, great Nature feared he might outvie Her works; and, dying, fears herself may die.”

Portraits by Raphael

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

Environment

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- A short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looksA short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looks

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

Travel

- Why this unlikely UK destination should be on your radarWhy this unlikely UK destination should be on your radar

- A slow journey around the islands of southern VietnamA slow journey around the islands of southern Vietnam

- Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?