Earth's Closest Cousin Discovered Among New Pile of Planets

Called Kepler 452b, the world is a bit bigger than Earth and could have a surface suitable for water and life.

In the twinkling of a distant star’s light, NASA’s ace planet-finders have spotted the signature of another Earth. Or rather, it’s the planet most like Earth that the Kepler mission has spied so far.

“It is the closest thing we have to another place that somebody else might call home,” Jon Jenkins of NASA’s Ames Research Center said Thursday at a press conference announcing the planet and a trove of 500 additional potential planets.

Called Kepler 452b, the planet orbits a six-billion-year-old sunlike star about 1,400 light-years away. Kepler 452b is about 60 percent larger than Earth, and perhaps five times as massive. With a year lasting 385 days, it sits in the region around its star where temperatures are just right for maintaining liquid water on a world’s surface.

It is the closest thing we have to another place that somebody else might call home.Jon Jenkins, Scientist

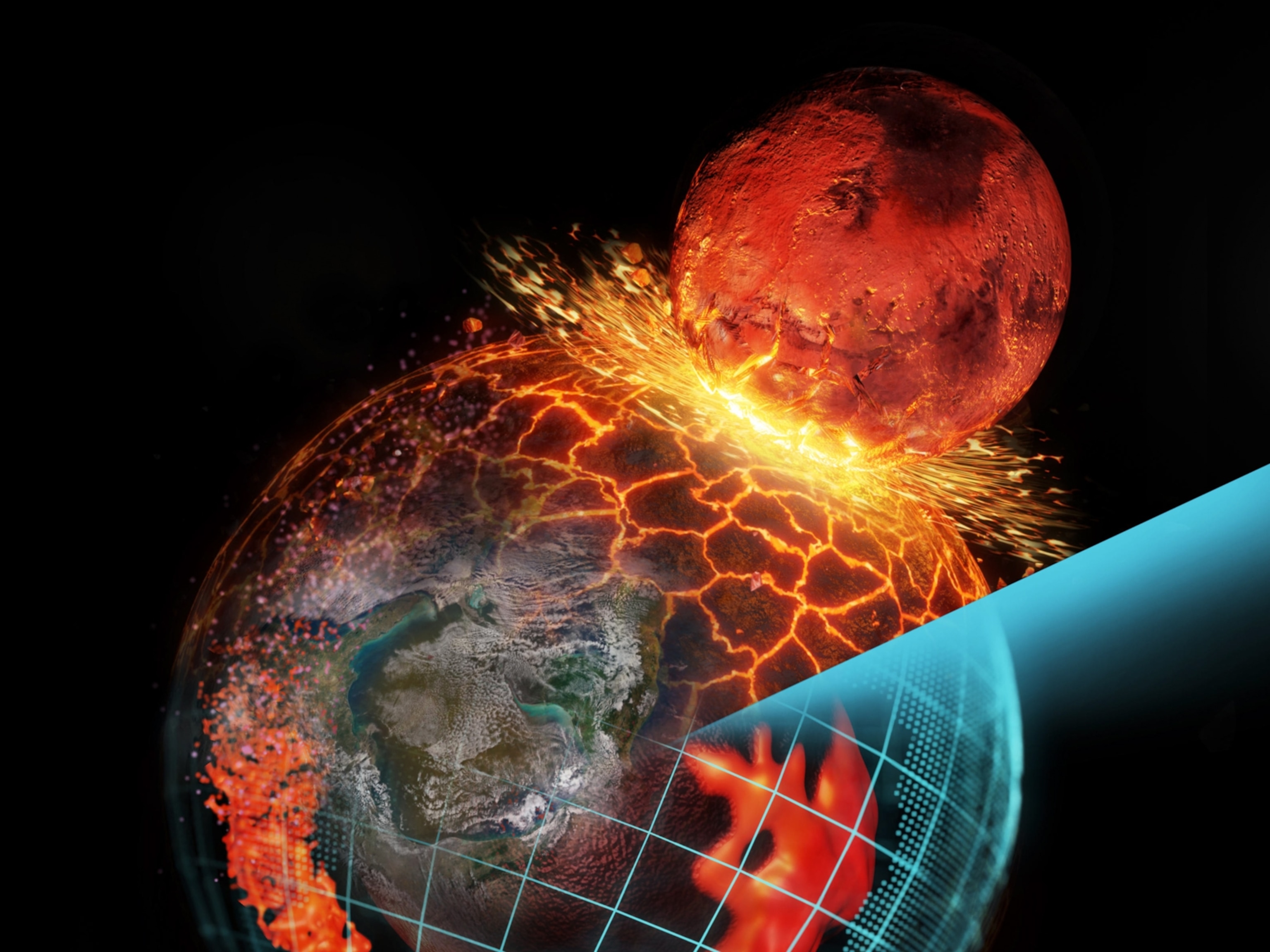

It’s not clear yet exactly what Kepler 452b is made of, but scientists think there’s at least a 50 percent chance it's rocky. If so, “we’d also expect the atmosphere to be thicker and have more cloud cover, and this planet would likely still have very active volcanoes,” Jenkins says.

A Sky Full of Planets

Launched in 2009, Kepler’s goal is to determine the prevalence of Earthlike planets in the Milky Way galaxy. For four years, Kepler stared at a patch of star-studded sky just above the galactic plane, watching 150,000 stars for the telltale twinkles produced when a distant planet briefly darkens its star’s face. (Read more about the new era in searching for life.)

A new haul of 500 planet candidates announced Thursday brings Kepler’s total catalog of possible planets to 4,696. Twelve of those are smaller than two Earth-widths, and nine orbit stars that are similar in size and temperature to the sun. More than 1,000 Kepler planets have been confirmed—and that’s just in one tiny piece of sky.

“When I was growing up, looking up at the stars, the question was, are there planets around those stars?” says NASA’s associate administrator John Grunsfeld. “We have a definitive answer. Most of the stars you see in the night sky have solar systems around them.”

But hints of the true Earth analogs—rocky planets orbiting sunlike stars at distances ripe for life—didn’t start emerging from those twinkles until last year. Now, we have more than a hint.

“I think 452b is really continuing in the process of zeroing in on the true Earth-sun analog,” says Natalie Batalha of NASA’s Ames Research Center. “Kepler 452b is the one that’s closest to the crosshairs.”

In Search of Earths

The team’s mission all along has been to figure out how common Earthlike worlds are. It’s a question with enormous implications for understanding whether life as we know it might be common in the universe. But answering that question proved difficult: The stars in Kepler’s field flickered more than expected, making it tricky to pull planet signatures from their twinkles. And in 2013, the Kepler spacecraft suffered an equipment malfunction and couldn’t continue its staring contest with the stars.

Now the potential Earths are finally emerging. And as each one is confirmed, scientists can refine their estimate for how common Earths are—a number that is crucial for designing future missions that will search for biosignatures around these worlds.

So far, Batalha says, it looks as though between 15 and 25 percent of stars might host an Earthlike world. “But we don’t know how common life is going to be,” she says. “It’s one thing to know how common planets are in the habitable zone. It’s a completely different thing to know how many of them are living worlds.”

And, as Kepler scientists continue combing through their catalog, other important planets will continue to emerge.

“There’s a lot more to come,” says Jeffrey Coughlin of the SETI Institute. “I really expect the discoveries will be coming from Kepler for the next several decades.”

Follow Nadia Drake on Twitter and on her blog at National Geographic's Phenomena.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- We finally know how cockroaches conquered the worldWe finally know how cockroaches conquered the world

- Move over, honeybees—America's 4,000 native bees need a day in the sunMove over, honeybees—America's 4,000 native bees need a day in the sun

- Surveillance Safari: Crowdsourcing an anti-poaching movement in South Africa

- Paid Content

Surveillance Safari: Crowdsourcing an anti-poaching movement in South Africa - Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- These are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and colorThese are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and color

- Why young scientists want you to care about 'scary' speciesWhy young scientists want you to care about 'scary' species

Environment

- Wildlife wonders: connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species

- Paid Content

Wildlife wonders: connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species - These images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new wayThese images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new way

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

History & Culture

- Should couples normalize sleeping in separate beds?Should couples normalize sleeping in separate beds?

- They were rock stars of paleontology—and their feud was legendaryThey were rock stars of paleontology—and their feud was legendary

- Scientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramidsScientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramids

Science

- Can a spoonful of honey keep seasonal allergies at bay?Can a spoonful of honey keep seasonal allergies at bay?

- Scientists just dug up a new dinosaur—with tinier arms than a T.RexScientists just dug up a new dinosaur—with tinier arms than a T.Rex

- Why pickleball is so good for your body and your mindWhy pickleball is so good for your body and your mind

- Extreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at riskExtreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at risk

- Why dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a rewardWhy dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a reward

Travel

- For an unexpected wellness break, head to the Dolomites' Alpe di SiusiFor an unexpected wellness break, head to the Dolomites' Alpe di Siusi

- The ‘Yosemite of South America’ is an adventure playgroundThe ‘Yosemite of South America’ is an adventure playground

- These farmers make it possible for hikers to access Alpine trailsThese farmers make it possible for hikers to access Alpine trails

- A guide to Philadelphia, the US city stepping out of NYC's shadowA guide to Philadelphia, the US city stepping out of NYC's shadow