On August 2, 1939, just a month before the outbreak of World War II, Dr. Einstein wrote a letter which made history. The letter was addressed to President Roosevelt, and it starts with the sentence: “Some recent work by E. Fermi and L. Szilard, which has been communicated to me in manuscript, leads me to expect that the element uranium may be turned into a new and important source of energy in the immediate future.” Dr. Einstein went on: “This new phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, . . . extremely powerful bombs. A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port, together with some of the surrounding territory.”

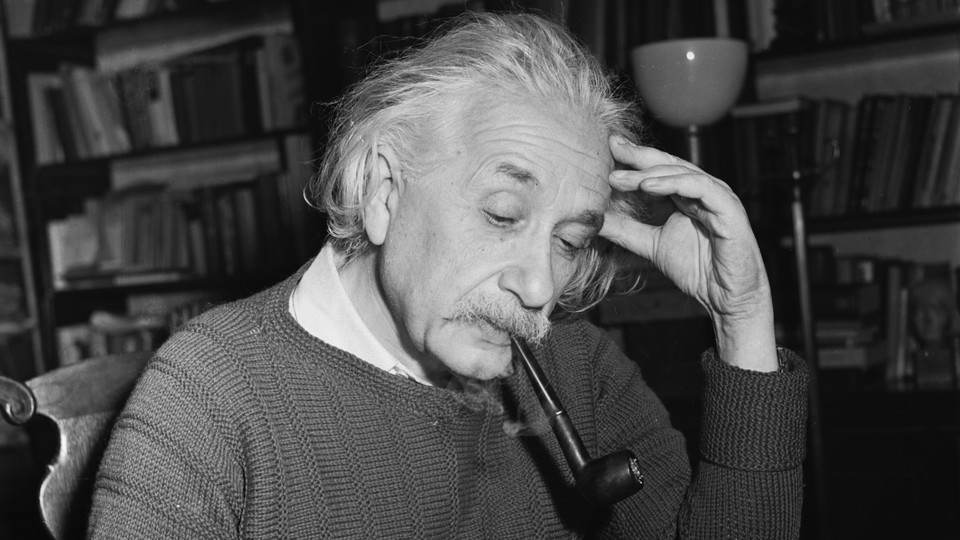

It was Einstein’s daring formula, E equals mc², which led to the concept that atomic energy would some day be unlocked. Here, in these words recorded by Raymond Swing, he explains how mankind must control atomic power.

THE release of atomic energy has not created a new problem. It has merely made more urgent the necessity of solving an existing one. One could say that it has affected us quantitatively, not qualitatively. As long as there are sovereign nations possessing great power, war is inevitable. That statement is not an attempt to say when war will come, but only that it is sure to come. That fact was true before the atomic bomb was made. What has been changed is the destructiveness of war.

I do not believe that civilization will be wiped out in a war fought with the atomic bomb. Perhaps two thirds of the people of the earth might be killed, but enough men capable of thinking, and enough books, would be left to start again, and civilization could be restored.

I do not believe that the secret of the bomb should be given to the United Nations organization. I do not believe that it should be given to the Soviet Union. Either course would be like the action of a man with capital, who, wishing another man to work with him on some enterprise, should start out by simply giving his prospective partner half of his money. The second man might choose to start a rival enterprise, when what was wanted was his coöperation.

The secret of the bomb should be committed to a World Government, and the United States should immediately announce its readiness to give it to a World Government. This government should be founded by the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain —the only three powers with great military strength. All three of them should commit to this World Government all of their military strength. The fact that there are only three nations with great military power should make it easier rather than harder to establish such a government.

Since the United States and Great Britain have the secret of the atomic bomb and the Soviet Union does not, they should invite the Soviet Union to prepare and present the first draft of a Constitution for the proposed World Government. That action should help to dispel the distrust which the Russians already feel because the bomb is being kept a secret, chiefly to prevent their having it. Obviously the first draft would not be the final one, but the Russians should be made to feel that the World Government would assure them their security.

It would be wise if this Constitution were to be negotiated by a single American, a single Britisher, and a single Russian. They would have to have advisers, but these advisers should only advise when asked. I believe three men can succeed in writing a workable Constitution acceptable to all three nations. Six or seven men, or more, probably would fail.

After the three great powers have drafted a Constitution and adopted it, the smaller nations should be invited to join the World Government. They should be free to stay out; and though they would be perfectly secure in staying out, I am sure they would wish to join. Naturally they should be entitled to propose changes in the Constitution as drafted by the Big Three. But the Big Three should go ahead and organize the World Government whether the smaller nations join or not.

The World Government would have power over all military matters and need have only one further power: the power to intervene in countries where a minority is oppressing a majority and creating the kind of instability that leads to war. Conditions such as exist in Argentina and Spain should be dealt with. There must be an end to the concept of non-intervention, for to end it is part of keeping the peace.

The establishment of the World Government must not have to wait until the same conditions of freedom are to be found in all three of the great powers. While it is true that in the Soviet Union the minority rules, I do not consider that internal conditions there are of themselves a threat to world peace. One must bear in mind that the people in Russia did not have a long political education, and changes to improve Russian conditions had to be carried through by a minority for the reason that there was no majority capable of doing it. If I had been born a Russian, I believe I could have adjusted myself to this condition.

It is not necessary, in establishing a world organization with a monopoly of military authority, to change the structure of the three great powers. It would be for the three individuals who draft the Constitution to devise ways for the different structures to be fitted together for collaboration.

2

Do I fear the tyranny of a World Government? Of course I do. But I fear still more the coming of another war or wars. Any government is certain to be evil to some extent. But a World Government is preferable to the far greater evil of wars, particularly with their intensified destructiveness. If a World Government is not established by agreement, I believe it will come in another way and in a much more dangerous form. For war or wars will end in one power’s being supreme and dominating the rest of the world by its overwhelming military strength.

Now that we have the atomic secret, we must not lose it, and that is what we should risk doing if we should give it to the United Nations organization or to the Soviet Union. But we must make it clear, as quickly as possible, that we are not keeping the bomb a secret for the sake of our power, but in the hope of establishing peace in a World Government, and that we will do our utmost to bring this World Government into being.

I appreciate that there are persons who favor a gradual approach to World Government even though they approve of it as the ultimate objective. The trouble about taking little steps, one at a time, in the hope of reaching that ultimate goal is that while they are being taken, we continue to keep the bomb secret without making our reason convincing to those who do not have the secret. That of itself creates fear and suspicion, with the consequence that the relations of rival sovereignties deteriorate dangerously. So, while persons who take only a step at a time may think they are approaching world peace, they actually are contributing, by their slow pace, to the coming of war. We have no time to spend in this way. If war is to be averted, it must be done quickly.

We shall not have the secret very long, I know it is argued that no other country has money enough to spend on the development of the atomic bomb, and this fact assures us the secret for a long time. It is a mistake often made in this country to measure things by the amount of money they cost. But other countries which have the materials and the men can apply them to the work of developing atomic power if they care to do so. For men and materials and the decision to use them, and not money, are all that is needed.

I do not consider myself the father of the release of atomic energy. My part in it was quite indirect. I did not, in fact, foresee that it would be released in my time. I believed only that release was theoretically possible. It became practical through the accidental discovery of chain reactions, and this was not something I could have predicted. It was discovered by Hahn in Berlin, and he himself misinterpreted what he discovered. It was Lise Meitner who provided the correct interpretation and escaped from Germany to place the information in the hands of Niels Bohr.

I do not believe that a great era of atomic science is to be assured by organizing sciences in the way large corporations are organized. One can organize to apply a discovery already made, but not to make one. Only a free individual can make a discovery. There can be a kind of organizing by which scientists are assured their freedom and proper conditions of work. Professors of science in American universities, for instance, should be relieved of some of their teaching so as to have time for more research. Can you imagine an organization of scientists making the discoveries of Charles Darwin?

Nor do I believe that the vast private corporations of the United States are suitable to the needs of these times. If a visitor should come to this country from another planet, would he not find it strange that in this country so much power is given to private corporations without their having commensurate responsibility? I say this to stress that the American government must keep the control of atomic energy, not because socialism is necessarily desirable, but because atomic energy was developed by the government and it would be unthinkable to turn over this property of the people to any individual or group of individuals. As to socialism, unless it is international to the extent of producing a World Government which controls all military power, it might more easily lead to wars than does capitalism, because it represents a still greater concentration of power.

To give any estimate of when atomic energy can be applied to constructive purposes is impossible. What now is known is only how to use a fairly large quantity of uranium. The use of quantities sufficiently small to operate, say, a car or an airplane is as yet impossible. No doubt it will be achieved, but nobody can say when.

Nor can one predict when materials more common than uranium can be used to supply atomic energy. Presumably all materials used for this purpose will be among the heavier elements of high atomic weight. Those elements are relatively scarce, because of their lesser stability. Most of these materials may already have disappeared by radioactive disintegration. So, though the release of atomic energy can be, and no doubt will be, a great boon to mankind, that may not be for some time.

I myself do not have the gift of explanation by which to persuade large numbers of people of the urgencies of the problems the human race now faces. Hence I should like to commend someone who has this gift of explanation — Emery Reves, whose book, The Anatomy of Peace, is intelligent, brief, clear, and, if I may use the abused term, dynamic on the topic of war and the need for World Government.

Since I do not foresee that atomic energy is to be a great boon for a long time, I have to say that for the present it is a menace. Perhaps it is well that it should be. It may intimidate the human race into bringing order into its international affairs, which, without the pressure of fear, it would not do.