Wonky lumps of misshapen, scorched bricks burst from a block of student flats in Cambridge, Massachusetts, giving a warty look to the long wall that winds its way along the Charles River. “The lousiest bricks in the world,” is how Finnish architect Alvar Aalto described the local New England materials he used for his Baker House dorms at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1947. It was meant as a compliment – he loved their twisted, blackened, brutish texture, which gave the walls the look of coarse tweed.

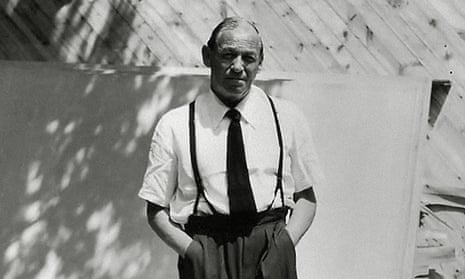

The pockmarked wall is one of many such strange and beautiful things covered in a new feature-length documentary film about Aalto, Finland’s most famous designer export and one of the most celebrated architects of the 20th century, who built a career on his obsessive attention to material details. Always thinking about the human experience of moving through a building, he considered everything from the feel of a leather-wrapped door handle to the pleasure of a misshapen brick.

The film follows in the footsteps of a number of other movies about modern masters, such as the tell-all quest to find the real Louis Kahn , made by his son, or the sycophantic biopic of Lord Norman Foster, which had the gloss of a promotional video. This falls somewhere between the two, full of admiration for the work of the charismatic Finn, featuring home cine films spliced with dreamy drone footage of his buildings, but not without revealing his less sympathetic sides.

Made by female director Virpi Suutari, the film does a good job of emphasising the vital contribution of Aalto’s wives – first Aino, and later Elissa – whose work has often been played down in the familiar narrative of the solo male genius. Described by one of the film’s many narrators as the “necessary balancing element” in Aalto’s otherwise “bohemian and erratic” life, it later becomes clear that Aino was, in fact, a crucial part of the Aalto atelier. And bohemian is a diplomatic way of putting it.

As well as being a qualified architect, Aino Aalto was a trained carpenter, which Alvar was not. She designed many of the buildings’ interiors, and was involved in creating the pioneering bentwood furniture that made Aalto a famous name internationally. She was also the chief designer and managing director of Artek, the company they founded in 1935 to manufacture their homewares, producing hundreds of textiles, lamps and glassware designs – many still on sale, and copied by countless other companies since.

That ribbed Ikea tumbler in your kitchen cupboard? It’s an Aino Aalto knockoff. Her input evidently extended deep into the architecture, too. “Regardless of how the drawings are signed, they clearly worked as a team,” says one narrator. “We’ll never know where the division is between the two.”

It was Aino who went out to work every day, we are told, while Alvar stayed in his studio at home. “I remember that he had an endless amount of time,” says his daughter, over photographs of her father lounging on a daybed and sunbathing on the beach. “He had occasional coffee breaks, he hummed, then he went into his office to draw a line or two, and then he came back again.” Aino, meanwhile, is constantly shown juggling work and children. As one voice puts it bluntly: “Alvar thought Aino’s job was to take care of him first, and then came the children, and then her work.”

We hear emotional letters the couple wrote to each other while they each travelled abroad for work, which hint at Aalto’s philandering. “You need to commit a whole lot of sin before we’re even,” he writes. “I have sometimes picked people up on the streets.” He finishes another letter: “Then to bed. (No girls.)” As for his drinking, Aino pleads for “not so many cocktails as last time”. Another narrator recalls the architect’s “erotic approach to life and work”, over footage of topless dancers in some kind of burlesque cabaret show. We’re left to fill in the blanks.

Perhaps he learned such behaviour from Frank Lloyd Wright. We are told that Aalto “changed completely as a person” after meeting him. Gone was the casual Finnish country attire, replaced instead with double-breasted suits. We hear of the Finn’s charming, gregarious nature and skill in networking, storytelling and acting, which earned him a reputation as a sought-after speaker. His friendship with Laurance Rockefeller led to an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1938, which catapulted the Aalto brand into the limelight. Their Finnish pavilion at the New York World’s Fair the following year was a sensation, leading Aalto furniture designs to become the single most popular brand of modern furniture in the US until the end of the 1940s.

Following Aino’s death from cancer in 1949, we see how Aalto devotes himself completely to work and launches into an energetic spree of building. He wins major competitions for the Helsinki University of Technology, the National Pensions Institute and Säynätsalo Town Hall – the last an enchanting civic complex nestled in a forest, like a sylvan parliament for Ewoks. “Humans belong to nature as much as pines and birches do,” Aalto said. “That’s where the scale comes from. I cannot ignore it. I cannot turn humans into giants or dwarves. I have to conform to the current human dimensions.”

In the 1950s, he dabbled in standardised housing in Germany, bringing a sense of human-centred flexibility to the plans, allowing the system to be modified according to the specifics of its location. He abhorred what he called the “vulgar functionalism” of so much prefabricated housing of the period, preferring to introduce curves and irregular angles wherever possible. When someone asked him what module he used, referring to which standardised construction system, he answered: “One millimetre.” Visiting his buildings today, that meticulous devotion to minutiae, and the craftsmanship of natural materials, is even more of a tonic, compared with how blunt and systematised so much contemporary construction has become.

His second wife, Elissa, gets less of a look-in, but we hear how the domineering architect tried to mould her into the image of Aino, even changing her hairstyle and insisting that she wore only black and white clothes. It seems she was just as crucial to the office as Aino had been, taking on the artistic responsibility of the atelier for the last 10 years of Aalto’s life.

Towards the end, he became increasingly introverted, bitter at what he saw as a lack of appreciation at home, despite his international fame. As commissions dried up, he turned to alcohol more and more, and withdrew into the cocoon of his office. He drew up a grand plan for central Helsinki, but only one part of it, Finlandia Hall, was ever built, completed in 1971, five years before his death. To younger generations, the experimental, radical Aalto of the 1930s had transformed into a conservative dinosaur by the late 60s, an overbearing presence to be rebelled against. To leftwing critics, he was the capitalist designer of banks, factories and head offices.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion