In the film Legend, which opens this fall, Tom Hardy plays the infamous English gangster Reggie Kray as well as his English-gangster brother, Ronnie. One day during filming, Hardy received a visit from Freddie Foreman, who is himself acquainted with criminal infamy. Foreman, now 83, was an alleged hit man for the real-life Krays (nickname: “Brown Bread Fred”). And Foreman had met Hardy back in 2008 when the actor was preparing for a different film, Bronson. As it happened, on the day Foreman visited the Legend set, the scene they were shooting — one in which members of a rival gang visit the Krays at a pub — re-created an event at which Foreman had been present in real life.

After chatting for a bit, Hardy excused himself — he had to get into his Ronnie Kray makeup. Though Reggie and Ronnie were identical twins, there were several physical differences between them, which Hardy was meticulous about imitating. Ronnie had a widow’s peak hairline. He wore glasses and favored double-breasted suits. He was heavier than Reggie, an effect that Hardy conjured through a simple realignment of his posture. Ronnie also had a broken nose, which Hardy mimicked by having a rubber baby-bottle nipple shoved up one nostril before Ronnie’s scenes.

When Hardy reappeared as Ronnie, Foreman was still talking with the crew. “So I just stood there. As Ronnie,” Hardy tells me. In Hardy’s recounting, Foreman turned to him, went quiet, staggered backward slightly, dumbstruck, then pointed a finger toward Hardy and said simply, “Fuckin’ ’ell.”

You might say that if Tom Hardy, who’s 38, isn’t the best film actor of his generation, he’s certainly in the conversation — except for the fact that Hardy keeps changing the conversation. Here is why Hardy is more impressive than your current favorite actor: Did your favorite actor once bring a notorious historical character to life? When Hardy played the charismatic, possibly psychotic prison boxing champion Charles Bronson in Bronson, he was so convincing he reportedly terrified members of the film’s crew. Did your favorite actor skillfully evoke a person hampered by physical limitations? Hardy once did an entire movie, Locke, in which he was driving a car, alone, having a series of conversations on speakerphone. Did your favorite actor reinvigorate a beloved action franchise? Earlier this summer, in Mad Max: Fury Road, Hardy not only reinvented an iconic character that had been in mothballs for 30 years (his formula: Double down on the “Mad” part, then double down again), he also gamely deconstructed the role of the action hero itself, in part by handing the rifle to his kick-ass female co-star Charlize Theron and letting her take the killing shot.

Every account of Tom Hardy’s career — he’s a much bigger star in the U.K. than he is, so far, in North America — will point to a “breakout” role, but there’s little agreement on exactly which role constitutes the breakout. For some, it was Bronson; for others, it was Bane in The Dark Knight Rises, if only because that film was such a big deal. (Hardy, who was impressive, was also largely obscured by a rubber-plunger cup of a mask.) Or perhaps the breakout came in an earlier Christopher Nolan film, Inception, in which Hardy played a debonair accomplice named Eames. His scenes were short and few but memorable enough that, when you walked out of the theater, he was the one who left you thinking: Wait a second — who was that? This is the recurring theme of Hardy’s Stateside film career: He is rarely the person who draws you to the movie, but he is reliably the person you remember best when it’s over.

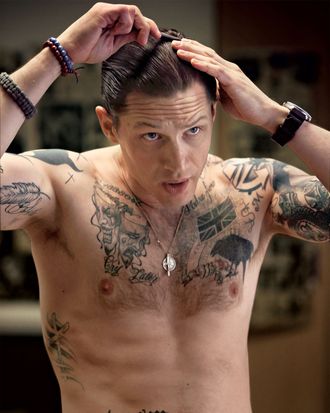

Hardy is also extremely good-looking — this isn’t my opinion, this is the internet talking — and by that simple calculus (very good actor, very good-looking), it seems strange he isn’t already a huge star. Yet at one point while I was talking about Hardy to my wife, she stopped me and said, “I have no idea who he is.” I struggled to think of a representative role, then realized there isn’t one. Instead, you have roles like the one Hardy played in the 2011 movie Warrior, in which he was cast as an MMA fighter opposite the Australian Joel Edgerton, who played his brother. Both characters are Irish-American, and together the actors provide dueling performances that recall Russell Crowe and Guy Pearce in L.A. Confidential — i.e., a reminder that, as with so many things that America used to lead the world in, we’ve pretty much forgotten how to make male movie stars. Which wouldn’t be a problem if an import like Hardy were interested in being a leading man. Instead, he’s more interested in tearing through challenging roles until he finds the one insurmountable acting challenge that will stump, defeat, or kill him. “Eventually, something will kill me. Of course it will,” he tells me. “Eventually, I’ll be rubbish. But if I don’t take on something that I feel will eat me alive, I don’t think I’d have the compulsion to work my ass off.”

If you ever have a chance to Skype with Tom Hardy, I’d highly recommend it. In fact, Skyping With Tom Hardy would make an excellent reality show. I’m in New York and he’s in London, where he’s just hosted the U.K. premiere of Legend, accompanied by the film’s writer and director, Brian Helgeland, and Hardy’s dog, Woody. I ask Hardy if he stayed to watch the film — many actors at such events slip away once the lights dim, either because they’ve seen the movie or they can’t stand to watch themselves onscreen. Hardy says he watched the film and he also watched the audience. “It’s good to keep an eye on something you’ve put into the world.” When I mention that not every actor would do that, he says, “Well, either they’re in a shit film or they’re not as involved in the process as much as they ought to be and could be. I feel like I’m duty bound to stand by it. And I care about it.”

To give you a flavor of what it’s like to Skype with him, imagine that Hardy is gesticulating so enthusiastically that it challenges the rendering capabilities of the screens’ pixels to keep up. He’s also vaping extravagantly. (I haven’t seen anyone attack a hookahlike smoking implement with such relish since the caterpillar in the cartoon version of Alice in Wonderland.) He’s sporting a shaved head and a scraggly, aggressively anti-glamorous beard. Hardy is not what you’d call polished, onscreen or off, but he’s outlandishly unpolished in a way that is, onscreen and off, very refreshing — and which is essential, no doubt, to his being as good as he is at what he does. He is, for example, the creator of one of the most legendary MySpace profiles of all time, which has been dissected and endlessly admired by websites like BuzzFeed. It contained photos of a nearly naked Hardy preening so unabashedly that you first assumed they had to be fakes. Then there’s the “About Me” bio, which was very long, in which he described himself like this: “I’m Grateful, arrogant self centred, tenacious, versatile, honest, honourable, loyal, loving, gentle, consistent, reliable, focussed, prideful, passionate and nuts,” and nothing about the rest of the bio will convince you any of those descriptions are untrue.

The MySpace page is no longer online, but Hardy shows little desire to rein himself in, even as his public profile grows; he recently said he’s “not remotely ashamed” of the photos. And, in conversation, once you get him going, he’ll unburden himself to you in a way that will make you believe he’s saying exactly what he’d say to a best mate. Or a therapist.

For example: the subject of directors. Hardy is on record as not being the biggest fan of directors, or at least not the ones in whom he loses faith. Hardy is enthusiastically, even obsessively, collaborative; this, to him, is where the joy in acting lies. He’ll watch playback of each take if the director lets him. Not every director likes to do this. “Sometimes a filmmaker might not want to tell you what he’s doing,” Hardy says. “He might not want to let you watch his dailies. And you go, ‘Oh, fuck it.’ Because then you have to do what they call ‘trust.’ Now why the fuck would I do that?” Hardy’s reportedly had his share of friction with directors (Nicolas Winding Refn, for one). Not Chris Nolan, though — he loves Nolan. He loves George Miller, who directed Mad Max. He loved working onstage under the direction of Philip Seymour Hoffman in the play The Long Red Road. And writers — he loves writers. He’s just not a big fan of so-called auteurs — you know, those fancy types who view actors as little more than chess pieces. “A writer comes with nothing and he writes something down and there’s a story,” says Hardy. “Then a bunch of actors come along, and people can watch that. Then a third person comes along and says, ‘I really love what you guys are doing. And if you’d just do it the way I see it, we’d really be onto something.’ And there’s part of me that goes: ‘Why are you here?’ A director who hasn’t written something, and they say, ‘Trust me.’ And I’m like, ‘With what, mate?’ ”

Hardy knows he has a reputation among some people for being difficult. “Knowing what the best idea is, having an open mind, and having the conviction that something’s going the wrong way — you fucking speak up, no matter how bad the reaction is from people who don’t want to hear it,” he says. “And you say, ‘This has to change, and I’m really sorry it’s going to fuck you all off, but we haven’t nailed it.’ They don’t like to hear that. So you’re difficult.” But the way he sees it, Hardy isn’t as hard on anyone else as he is on himself. “Everyone wants to be excellent. And if you’re striving for that excellence, and it’s expected from me, then I expect that from you.”

Hardy, who completed a grueling six-month shoot in 2012 in Namibia for Mad Max, followed it with an even more grueling, eight-month shoot in Alberta and Argentina for Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Western thriller The Revenant, set for release on Christmas, which co-stars Leonardo DiCaprio as a vengeful fur trapper. When I mention the movie, Hardy jokingly calls it Forever and Evenant. “Yeah, I was never not going to make it out of that movie alive, mate,” he says. “But it was fucking epic. Alejandro picked up from Birdman and decided to take everything he did in that and make it work in the great outdoors, in natural light, in minus-20 degrees Celsius.” The shoot was overbudget and overschedule, and many crew members quit. But you get the sense this is exactly the kind of recklessly insane undertaking Hardy loves to sign up for. “It was fucking hard,” he says. “I think [Alejandro] bit down hard on something that bit him back. And he bit back as well. And it continued to be a beast that was biting him, and he was biting it, and we all bit down.” The result, he promises, will be “fucking awesome.”

In the meantime, you can enjoy two great Hardy performances, conveniently contained in one new movie. When Helgeland set out to cast the twin brothers, he wasn’t sure if he wanted one actor or two. “Two actors is limiting, because they have to look alike,” he says. “I could never have, say, Benedict Cumberbatch play Ron, because you’d never believe he and Tom are brothers. But the reverse is, with one actor, if it’s a gimmick and people can’t get past it, then the movie is doomed from before you even start shooting.” He liked Hardy for the lead role of the more glamorous Reggie; Hardy, naturally, was more drawn to Ron. “If you’re Tom, that’s obviously the part that’s more appealing,” says Helgeland. “His desire is to be a character actor because the parts are more interesting, so he tries to hide his leading-man abilities.” They met for dinner, and at the end of the meal, Hardy made him a proposition. “He said, ‘You give me Ron, and I’ll give you Reggie,’ ” says Helgeland. “And that decision that was either going to make or break us was made.”

Hardy is often compared to Marlon Brando, but he is not a practitioner, nor a fan, of Method acting. “I respect it, it has a place, but it was more of a Zeitgeist thing, from Strasberg and Stella Adler and that kind of stuff, Meisner and God knows what, Stanislavski,” he says. He’s classically trained in the standard way of a London actor; he also has had essentially two acting careers. He appeared, in his early 20s, in roles such as a soldier in Black Hawk Down and a clone of Captain Picard in Star Trek: Nemesis. Then he ran into addiction issues, most dramatically with crack. In his telling, he almost died. Then he kicked his addictions. Then he resumed acting, with a renewed, exuberant, ex-addict’s energy. Rather than engage in what he terms “gritty realism,” he likes to create characters that border on caricature. “It’s what I like to call Disney World meets Taxi Driver,” he says. “You’re laughing along with all the fun, and it’s all good, and you’re immersed in a colorful, cartoonlike world. Then you ground it with something really honest — where you change the tone completely. It’s like putting a hypodermic needle into a candy floss and giving it to a child. It’s wrong,” he says. “It’s fucking wrong.”

The next challenge for Hardy will be to figure out what happens when Disney World meets Taxi Driver meets Hollywood leading man. Interestingly, even as you’re marveling at the technical virtuosity of his twinned performances in Legend, the film’s Swinging London setting, sharkskin suits, and casino backdrops all reinforce the notion that Hardy would make an excellent James Bond. “He obviously does a great job as Ron, but I’m excited that, for the first time in his career, as Reggie, he struts the movie-star stuff,” says Helgeland. “He’s handsome and well groomed, he looks sharp, he plays strong and silent — all the things he’s tried to avoid in his career. And because he had Ron at the end of the day, he was happy to do Reg. But it’s the Reggie no one’s seen Tom play before, not Ron.” The transition to traditional leading-man roles might seem like a natural progression, but it would also be an unfortunate diversion. As a Hardy fan, I was relieved that Mad Max: Fury Road wasn’t a typical star turn, if only because it meant that the day when his name will loom over movie posters — when no one anywhere will be able to say, “I have no idea who he is” — has been postponed, if just for a little while longer.

*This article appears in the September 21, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.