Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

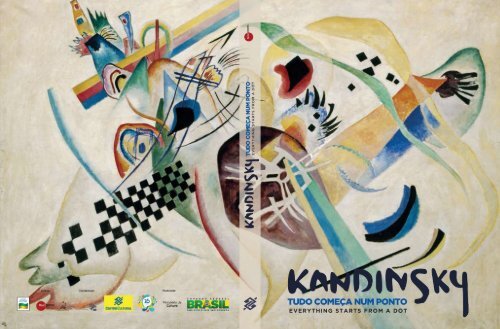

MUSEU ESTATAL RUSSO, SÃO PETERSBURGOCENTRO CULTURAL BANCO DO BRASIL, BRASÍLIA, RIO DE JANEIRO, SÃO PAULO, BELO HORIZONTE//CENTRO CULTURAL BANCO DO BRASIL, BRASÍLIA, RIO DE JANEIRO, SÃO PAULO, BELO HORIZONTESTATE RUSSIAN MUSEUM, ST. PETERSBURGWASSILYTUDO COMEÇA NUM PONTO // EVERYTHING STARTS FROM A DOT<strong>KANDINSKY</strong>

exposição / exhibitionpatrocínio / sponsored byBanco do Brasilrealização /organized byCentro Cultural Banco do Brasilcuradoria / curatorshipEvgenia PetrovaJoseph Kiblitskyprodução / productionArte A Produçõesdireção geral / general directionRodolfo de Athaydecoordenação geral / general coordinationAnia Rodríguezgerenciamento de projeto /project managementJennifer McLaughlindesign gráfico e expográfico /graphic and exhibition designBete Esteves — Complexo DLucas BevilacquaJulia Arbexequipe de produção / productionKaren ItuarteDaniele OliveiraMonique Santosgestão financeira / financeLisiany MayãoAnderson Oliveiraassessoria de imprensa / press relationsTales Rochatransporte internacional /international transportHasenkamp Russian Museumtransporte nacional / national transportMillenium Transportesagente alfandegário / customs agentMacimportcatálogo / cataloguediretor do Museu Russo /director of the Russian MuseumVladimir Guseveditor-chefe / editor-in-chiefEvgenia Petrovaconcepção do catálogo /conception of the catalogueEvgenia PetrovaJoseph Kiblitskyartigos / articlesEvgenia PetrovaSergio PoggianellaChristian MeyerAlexander PavlenkoRodolfo de AthaydeAnia Rodríguezcoordenação de catálogo versão Português /catalogue coordination of Portuguese versionLaura CosendeyMaria Alice Najoumtraduções / translationPeter Bray (Russo–Inglês /Russian–English)Klara Gourianova (Russo–Português /Russian–Portuguese)Fabiana Motroni (Italiano–Português /Italian–Portuguese)Grupo Primacy (Português–Inglês /Portuguese–English)Vanessa Prolow (Russo–Inglês /Russian–English)Fernanda Romero (Alemão–Português /German–Portuguese)versão em português de poemas de Kandinsky /Portuguese version of Kandinsky’s poemsAnabela Mendesrevisão / proofreadingAna Tereza Andrade (Português / Portuguese)Allan Araújo (Português / Portuguese)Galina Maximenko (Inglês / English)Elena Naydenko (Inglês / English)layout do projeto e design /design and computer layoutKirill Shantgaiagradecimentos / acknowledgementsAndrey BudaevCônsul Geral da Rússia no Rio de Janeiro /Russian Consul General in Rio de JaneiroAntonio Alves Jr.Diretor de Relações Internacionaisdo Ministério da Cultura /Director of International Relationsof the Ministry of CultureGilberto RamosAlexei BlinovLuiz Ludwigconteúdo / contentsAPRESENTAÇÃOFOREWORDCentro Cultural Banco do Brasil/6/PONTO DE PARTIDASTARTING POINTAnia Rodríguez, Rodolfo de Athayde/8/<strong>KANDINSKY</strong> NO CONTEXTO DA CULTURA RUSSA DO FIM DO SÉCULO XIX E DO COMEÇO DO SÉCULO XX<strong>KANDINSKY</strong> IN THE CONTEXT OF TURN-OF-THE-20TH-CENTURY RUSSIAN CULTUREEvgenia Petrova/10 /O OBJETO COMO ATO DE LIBERDADE. KANDISNKY E A ARTE XAMÂNICATHE OBJECT AS AN ACT OF FREEDOM. <strong>KANDINSKY</strong> AND SHAMAN ARTSergio Poggianella/28 /INOVAÇÃO E TRANSFIGURAÇÃO DE MÍDIA —SOBRE O COMPOSITOR WASSILY <strong>KANDINSKY</strong> E O PINTOR ARNOLD SCHÖNBERGINNOVATION AND TRANSFIGURATION OF MEDIA —ABOUT THE COMPOSER WASSILY <strong>KANDINSKY</strong> AND THE PAINTER ARNOLD SCHÖNBERGChristian Meyer/40 /A VANGUARDA ANIMADATHE ANIMATED AVANT-GARDEAlexander Pavlenko/50 /<strong>KANDINSKY</strong>E AS RAIZES DE SUA OBRA // AND THE ROOTS OF HIS OEUVREMÜNTER // BEKHTEEV // STELLETSKYROERICH // VASNETSOV/59 /<strong>KANDINSKY</strong>NA ALEMANHA // IN GERMANYMÜNTER // JAWLENSKY // WEREFKIN // SCHÖNBERG/87 /<strong>KANDINSKY</strong>IMPROVISAÇÕES // IMPRESSÕES // ÍCONES // XAMANISMOIMPROVISATIONS // IMPRESSIONS // ICONS // SHAMANISM/109 /fotografia / photographyVladimir DorokhovGrigory KravchenkoMark SkomorokhARTE FOLCLÓRICA // FOLK ART/138/© State Russian Museum© FSP Fondazione Sergio Poggianella© Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna© Private collection, Vienna© Private collection, New Jersey, USA© Vladimir Tsarenkov collection© Stella and Vadim Aminov collection© ADAGP© Boris Kustodiev Picture Gallery, Astrakhan© Irkutsk Museum of Regional Studies© National Museum of Modern Art, Pompidou Centre, Paris© Primorskaya State Gallery, Vladivostok© Mikhail Vrubel Regional Museum of Fine Arts, Omsk© Nizhny Novgorod State Art Museum© Krasnoyarsk Art Museum© State Museum of Fine Arts of theRepublic of Tatarstan, Kazan© Anatoly Lunacharsky Museum of Art, Krasnodar© Regional Museum of Local History, Tyumen© Palace EditionsPrinted in Italydiretor da arte da editora /art director of the publishing houseJoseph Kiblitsky© Kandinsky, Wassily / Licenciado por AUTVIS, Brasil, 2014© Succession Pablo Picasso / Licenciado por AUTVIS, Brasil, 2014© Münter, Gabriele / Licenciado por AUTVIS, Brasil, 2014© Jawlensky, Alexej von / Licenciado por AUTVIS, Brasil, 2014© Schönberg, Arnold / Licenciado por AUTVIS, Brasil, 2014© Baranoff-Rossiné, Vladimir / Licenciado por AUTVIS, Brasil, 2014SIMBOLISMO, PRIMEIRA ABSTRAÇÃO NA RÚSSIASYMBOLISM, EARLY ABSTRACTION IN RUSSIA/146/<strong>KANDINSKY</strong>BREVE BIOGRAFIA // SHORT BIOGRAPHY/172 /BREVE BIOGRAFIA DOS ARTISTASSHORT BIOGRAPHIES OF ARTISTS/178 /

6/Banco do Brasil apresenta “Kandinsky: tudo começa num ponto”, exposiçãodo artista Wassily Kandinsky, um dos mais renomados mestresda pintura moderna, pioneiro e fundador da arte abstrata, que revolucionoutoda a arte do século XX.Ao lado de trabalhos de seus contemporâneos e de artistas que o influenciaram,a exposição apresenta a obra de Kandinsky de forma holística,para entendermos como essas influências ecoam ainda hoje naarte contemporânea. O acervo terá como base a coleção do Museu EstatalRusso de São Petersburgo, além de oito museus do interior da Rússiae coleções particulares.Ao realizar a mostra, o Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil possibilita àsociedade brasileira o contato com obras-primas de grandes nomes dahistória da arte e reafirma seu comprometimento com a formação de públicoe com o acesso à cultura cada vez mais amplo.Banco do Brasil presents Kandinsky: Everything Starts from a Dot, an exhibitionof the artist Wassily Kandinsky, one of the most reputed masters of modernpainting, pioneer and founder of abstract art, who revolutionized20th-century art.Alongside works by his contemporaries and by artists that influencedhim, the exhibition presents Kandinsky’s art holistically in order to understandhow those influences still echo in contemporary art today. The majority ofthe works on display were selected from the collection of the State RussianMuseum in St. Petersburg, but there are also loans from 8 museums in smallerRussian cities as well as from private collections.By presenting this exhibition, the Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil offersthe Brazilian public contact with masterpieces by the great names in arthistory and reaffirms its commitment to education and broadening accessto culture./7/Centro Cultural Banco do BrasilCentro Cultural Banco do Brasil

PONTO DE PARTIDASTARTING POINT/8/Os caminhos iniciados por Kandinsky ecoam na arte até os dias de hoje. Entender esse gênio criativo implica tambémentender a sensibilidade que marca a arte desde o início do século XX. Esta exposição apresenta o prólogo dessahistória enriquecida que é a arte moderna e contemporânea: o modo em que se forjou a passagem para a abstração,os recursos a partir dos quais a figuração deixou de ser a única via possível para representar os estados mais vitais doser humano e, finalmente, o novo caminho desbravado a partir dessa ruptura. Esse salto para o vazio que a abstraçãorepresenta, a abertura de um universo sem fronteiras para a criatividade infinita da arte, pode ser vivenciado na partefinal dessa mostra que, como em suspenso, aponta um novo modo de pensar a arte.E é o próprio artista, prolífico também no campo da escrita, que nos guia por esse caminho através de inúmerostextos teóricos, e acaba por nos acompanhar no percurso, repetindo conosco os passos que ele mesmo trilhou. Convoca-setoda a influência da arte popular e a mítica ancestral dos povos do Norte da Rússia como parte deste despertarpara a expressão de uma sensibilidade íntima e lírica da alma. Ainda juntam-se a nós outros artistas contemporâneosa Kandinsky, com produções e maneiras particulares de refletir essas mesmas questões, artistas com os quais possuíauma relação estreita e nutria esse diálogo transformador acerca das potencialidades reservadas para a arte nos primórdiosdo século XX. Essas conversas são potencializadas pelos artistas que faziam parte do grupo Der Blaue Reiter(“O Cavaleiro Azul”) e na fraterna comunicação com Arnold Schönberg, que personifica o diálogo entre música e pintura,que se torna elemento fundamental na teoria estética de Kandinsky.Para além das imagens tipicamente identificadas com o artista, pinturas que o fazem reconhecido em qualquer partedo mundo, o projeto de curadoria que inspirou essa exposição se compromete a trazer ao público um Kandinsky poucoconhecido, com produções variadas que tecem entre si uma obra maior do artista, experimental, multissensorial, comotoda a essência de sua arte. A poesia que faz parte de seu livro ‘Sonoridades’ — que ainda aguarda ser publicado emportuguês —, reunida aqui em belíssimas e inéditas traduções, parece sussurrar para nós os segredos de sua alma.Essa alma russa, profunda, errante, que se lança em viagens e se enriquece em suas experiências na Alemanha e naFrança, países que o recebem como um dos seus, agora se revela e se descobre no Brasil.A mostra de Kandinsky, razão de ser deste catálogo, é resultado da construção de um relacionamento de confiançae maturidade entre o Museu Estatal Russo de São Petersburgo, o Centro Cultural do Banco do Brasil e a Arte A Produções,relação frutífera que tem seus antecedentes no sucesso de um trabalho anterior, a exposição “Virada Russa”(realizadaem 2009, no circuito do CCBB). Na Virada Russa, tínhamos como motivação confrontar o público brasileiro com umadas matrizes fundamentais da arte moderna, a vanguarda russa, que, com toda a sua multiplicidade e explosão criativa,influenciou profundamente as tendências dominantes das artes no Brasil, a partir dos anos 1950, especialmente o concretismobrasileiro e seus desdobramentos.A riqueza e a importância da obra de Wassily Kandinsky — e o fato de nunca antes ter sido realizada no Brasil umaexposição dedicada a este ícone da arte — foi um fator de peso para mergulharmos na criação deste projeto, mas foia profunda relação de parceria e os valores humanos e artísticos compartilhados com Evgenia Petrova e Joseph Kiblitskyque tornou possível o sonho de um empreendimento dessa magnitude. Evgenia Petrova, diretora científica do MuseuRusso, é uma figura lendária que se apresenta como a “guardiã” dos 400 mil tesouros que sobreviveram a uma revoluçãosocial, duas guerras mundiais e a sanha de uma visão autoritária imposta à cultura nos períodos mais controversosda Ex-União Soviética, e, sob sua custódia e de muitos outros anônimos, foi possível salvar estas obras para opatrimônio cultural da humanidade.Essa exposição sobre Kandinsky é uma mostra única, que não apenas apresenta uma sequência de quadros dopintor, pensador e escritor que foi o artista, mas um mergulho nas profundezas das raízes do seu universo criativo, nasreferências primeiras do artista, colocando lado a lado suas obras com as obras dos seus contemporâneos e outraspeças que são joias da arte popular do norte da Sibéria e dos objetos de rituais xamânicos.Conheceremos um Kandinsky quase oculto na visão ocidental que se tem sobre o artista e encontraremos tambémum Kandinsky poético e lírico, no momento de seu auge criativo, no exato instante das suas descobertas. Este é o grandevalor deste projeto e da curadoria de Petrova e Kiblitsky: uma exposição forte e desafiadora, que teve que ser defendidacom muito tesão e paixão pela arte e pelo conhecimento, fruto de um enorme esforço de todas as partes envolvidas,e é dedicada a um público ávido e cada vez mais exigente, como o brasileiro, e aberta democraticamente a todos.Tudo começa num ponto, a frase antológica de Kandinsky, nos conduz para além das experimentações gráficas doartista e nos transmite a essência poética que aponta a essa complexa trama de referências, vontades e sensações —muito mais que um ponto — onde tudo em Kandinsky começou.The journey started by Kandinsky still echoes in art to the present day. Understanding this creative genius also means understandingthe sensitivity that marks art from the early 20th century. This exhibition presents the prologue of this rich storyof modern and contemporary art: how the passage to abstraction was made, the resources from which recognizablefigures were no longer the only possible way to represent the most vital states of the human being, and, ultimately, thenew path opened from this rupture. This leap into the vacuum that abstraction represents, the opening of a boundless universefor the infinite creativity of art, may be experienced in the final part of this exhibition, which points at a new way ofthinking about art.The artist himself, also prolific in the field of writing, guides us along this path using countless theoretical texts, and heends up following us along this route, repeating the steps he took. All the influences of folk art and mythical ancestry of thepeople of Northern Russian are invoked as a part of this awakening, to express an intimate and lyrical sensitivity of thesoul. Other artists who were contemporaries to Kandinsky also join us, with specific creations and ways of thinking aboutthose same issues, artists with whom he had a close relationship and carried out this transformational dialogue about thepossibilities of art at the beginning of the 20th century. Those conversations are empowered by artists who belonged toThe Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) and in the fraternal communication with Arnold Schönberg, which personifies the dialoguebetween music and painting, an essential element in aesthetic theory of Kandinsky.In addition to the images typically associated to the artist, paintings that gave him worldwide recognition, the curatorialproject that inspired this exhibition aims to show the audience a lesser-known Kandinsky, with varied productions that togetherresult in a larger, experimental, multisensory body of work by the artist, like the entire essence of his art. Poetry fromhis book “Sounds” — still not published in Portuguese — is gathered here in beautiful translations, and the poems seem towhisper to us the secrets of his soul. That deep, wandering Russian soul, ever-travelling and enriched from his experiencesin Germany and France, countries that welcomed him as one of their own, is now revealed and finds itself in Brazil.This Kandinsky exhibition, raison d’être of this catalogue, is the result of a relationship of trust and maturity between theState Russian Museum, in St. Petersburg, Banco do Brasil Cultural Centers, and Arte A Produções, a fruitful relationshipwith a history of success due to the exhibition “Russian Turning”, exhibited in the CCBB circuit in 2009. In “Russian Turning”,our motivation was to show the Brazilian audience one of the essential matrixes of modern art, the Russian Avant-garde,which, with all its plurality and creative explosion, deeply influenced the dominating trends of arts in Brazil from the 1950s,especially Brazilian Concretism and its ramifications.The richness and importance of Wassily Kandinsky’s work, and the fact that Brazil had never had an exhibition dedicatedto this art icon, were important factors in our decision to dive into the creation of this project. But it was our profound partnershipwith Evgenia Petrova and Joseph Kiblitsky, as well as the human and artistic values shared with them, which alloweda dream of such huge undertaking. Evgenia Petrova, Deputy Director of the Russian Museum for Academic Research, is alegendary figure who appears to my eyes as the “guardian” of the 400,000 treasures that survived a social revolution,two World Wars, and the wrath of an authoritarian view imposed on culture during the most controversial periods of theformer Soviet Union. Under her custody, and of many other anonymous people, it was possible to save those works for theworld’s cultural heritage.This exhibition on Kandinsky is unique, showing not only a sequence of works by the painter, thinker and writer theartist was, but also delving deep into the roots of his creative universe, to his primary references, placing his works sideby-sidewith those of his contemporaries, with works which are jewels of folk art from Northern Siberia and with objectsfrom shamanic rituals.We will get to know a Kandinsky which has practically been hidden from the western eye, and we will also find a poeticand lyrical Kandinsky, at his creative peak, at the exact time of his discoveries. This is the great value of this project and ofthe curatorship of Petrova and Kiblitsky: a strong and challenging exhibition, which was defended with a passion for artand knowledge, the result of massive efforts from all those involved. This exhibition is dedicated to the avid, increasinglydemanding Brazilian public, and is democratically open to all.“Everything starts from a dot,” an anthological quote by Kandinsky, leads us beyond the artist’s graphic experimentations,conveying the poetic essence that indicates the complex web of references, desires, and sensations — much morethan a point — where it all started in Kandinsky./9/Ania Rodríguez e Rodolfo de Athayde Ania Rodríguez and Rodolfo de Athayde

<strong>KANDINSKY</strong>NO CONTEXTO DA CULTURA RUSSA DO FIM DO SÉCULO XIX E DO COMEÇO DO SÉCULO XXIN THE CONTEXT OF TURN-OF-THE-20TH-CENTURY RUSSIAN CULTUREEvgenia PetrovaKandinsky em seu apartamento na rua AinmillerMunique, 1911Kandinsky’s Ainmiller Straße flatMunich, 1911A obra de Wassily Kandinsky é bem conhecida há muitotempo. No entanto, não são raros os casos quando “escapam”da atenção do público detalhes interessantes esignificativos que formaram a concepção artística do pintor.A maior parte da exposição, apresentada hoje ao públicobrasileiro, é dedicada justamente a esses pormenoresque explicam e completam o nosso conhecimento sobreKandinsky.Ao selecionarmos obras para essa exposição, seguimosa biografia do artista até sua partida definitiva daRússia, em 1922, e recorremos a suas memórias (“Degraus”),artigos 1 e catálogos das exposições organizadasdurante a vida do pintor, especialmente “O CavaleiroAzul” 2 e o “Salão de Izdebsky”. 3 Como isso nos ajuda aentender Kandinsky? A nosso ver, o contexto em meio aoqual Kandinsky se formava como artista plástico é um fatormuito importante.“Nasci em Moscou em 5 de dezembro de 1886” —escreveu Kandinsky em autobiografia que precede o catálogoda exposição de suas obras entre os anos 1902–1912. “Até meus trinta anos de idade, eu sonhava emme tornar pintor, amava a pintura acima de tudo, masachava que, para um homem russo, a arte era um luxoinadmissível. Por isso, na universidade, escolhi a EconomiaNacional como minha futura profissão…” 4Foi justamente esta especialização que o levou, em1889, à região de Vologda, no Norte da Rússia. Estudoucom muita seriedade a vida, os costumes e a situaçãoeconômica do povo dessa região, em cuja história se misturaramraízes russas e finlandesas. Nesse período, Kandinskyencontrou vários artigos científicos dedicados aopovo Zyriane * . Mas o que ele trouxe de seu contato comos Kómi e com a terra nórdica foi, principalmente, o amorpor essa gente simples e até primitiva, por seu modo devida e a sua arte.Naquela época, fim dos anos 1880, causaram-lheuma grande impressão os rituais e as crenças dos povosnórdicos que conheceu ou soube através de seus amigosetnógrafos. Assim, Nikolai Ivanitsky, que Kandinsky mencionouem “Degraus”, contava ao futuro pintor sobre osKómi idólatras que sacrificavam animais como oferendasa seus deuses. 5 Nikolai Kharuzin, pesquisador das raízesxamanistas dos bruxos contemporâneos do povo Lopari,denominou em seu livro o fetichismo e o xamanismo como“religião da magia”. O cientista encontrou rastros do xamanismona obra épica finlandesa “Kalevala”, onde aLaplândia ** foi descrita como um país povoado por feiticeiros.6 Kandinsky leu “Kalevala” e comentou o livrocom grande entusiasmo. “Li ‘Kalevala’. Admiro” — anotouem seu diário de 1889. 7Sem dúvida, Kandinsky conhecia bem o xamanismo,inclusive pelo livro de Nikolai Kharuzin, para o qual escreveuuma resenha. 8 Além disso, na Rússia do fim do séculoXIX, o interesse pelo Norte e pela Sibéria cresciamuito, assim como pelas antigas raízes que permaneceramna cultura russa depois da conversão ao cristianismo.De certo modo, esse processo fazia paralelo com a paixãopelas antiguidades africanas e orientais que criou oprimitivismo ocidental. E não se pode negar que o interessepela Sibéria e pelo Norte também tinha a ver comobjetivos práticos.*Nome de parte do povo Kómi, para diferenciá-los dos Kómi da provínciade Perm. (N. da T.)**Atualmente Finlândia. (N. da T.)Wassily Kandinsky’s art enjoys a long-established renown.However, as is often the case, certain highly important andinteresting facts about the artist’s life have escaped the public’sattention, facts that played a significant role in forminghis creative world-view. Dedicated in large part to these bio -graphical facts, the exhibition being presented to Brazilianmuseum-goers today should do much to explain and expandon what we already know about Kandinsky.In preparation for the exhibition, we began reviewingKandinsky’s biography up to the moment of his final departurefrom Russia in 1922. Our primary sources were the artist’sreminiscences in Stupeni (Steps), his articles 1 and the cataloguesof his lifetime exhibitions, in particular with Der BlaueReiter 2 and the Izdebsky Salons. 3 What, in our view, do thesematerials add to our understanding of Kandinsky? One veryimportant thing above all, namely the context in which his formationas an artist occurred.“I was born in Moscow on 5 December 1866,” writesKandinsky in the autobiographical introduction to an exhibitionof his works dating from 1902 to 1912. “Until age thirtyI dreamed of becoming a painter, as I loved painting morethan anything else. It was difficult for me to overcome this desire.But art seemed to me an impermissible luxury for a Rus -sian at the time, so I chose to specialize in national economicsat university.” 4It was this specialization that brought Kandinsky in 1889to Vologda Gubernia in the Russian North as part of an expeditionduring which he made a serious and detailed investigationof the life, ways and economic circumstances of theKomi-Zyrian people. Kandinsky went on to write severalscholarly articles about this ethnic group with Russian andFinno-Ugric roots. But the main thing he gained from his contactwith the Zyrian people and the northern region was alove for the culture and lifestyle of these simple, even primitive,folk.The rituals and beliefs of the northern peoples that theartist became acquainted with directly and through his ethnographerfriends produced an enormous impression on himthen, in the late 1880s. Nikolai Ivanitsky, whom Kandinskymentions in Stupeni, enlightened the future artist about Zyrianpaganism and animal sacrifices. 5 Nikolai Kharuzin was a researcherof contemporary Lapp sorcerers and their shamanistictraditions who characterized fetishism and shamanismas “religions of magic” in his writings. Kharuzin investigatedthe shamanistic roots of the Finnish epic Kalevala, in whichLapland is described as a country inhabited by wizards. 6Kandinsky read the epic too and was enthralled: “I’ve readKalevala. I bow down in respect,” he writes in his diary in1889. 7Kandinsky was undoubtedly familiar with shamanism bothfrom Nikolai Kharuzin’s book, for which he wrote a review, 8and other sources. Late-19th century Russia as a whole wasexperiencing a resurgent interest in the North, Siberia and thepre-Christian roots of Russian culture. To a large degree, thisprocess paralleled the interest in African and Oriental antiquitiesthen taking place in the West, which formed the basisof Western Primitivism. In Russia, however, the interest in theNorth and Siberia was in large part connected with practicalconcerns.At that time, as in earlier periods, incidentally, numerousexpeditions were organized to study the rich mineral resourcesof Russia’s far-flung regions. Encountering naturalwonders and native peoples whose existence and waysthey’d formerly known nothing of, the artists traveling with/ 11 /

<strong>KANDINSKY</strong> NO CONTEXTO DA CULTURA RUSSA DO FIM DO SÉCULO XIX E DO COMEÇO DO SÉCULO XX // <strong>KANDINSKY</strong> IN THE CONTEXT OF TURN-OF-THE-20TH-CENTURY RUSSIAN CULTURENaquela época e até antes, as expedições com a finalidadede estudar regiões longínquas, ricas em minérios,eram bastante frequentes. Os pintores participantesdessas expedições, ao se depararem com a natureza, vidae hábitos desconhecidos dos povos Samoiedos 9 , deixaramtestemunhos formidáveis de suas impressões, nãosomente em pinturas e aquarelas, mas em memórias,contos e correspondências. Alexander Borisov, consideradoo descobridor do Ártico, é autor de monumentais elacônicas paisagens em aquarela, nas quais seus personagensprincipais são rochas cobertas de neve e espaçossem limites. Procurando os lugares onde os samoiedosfaziam seus rituais e sacrifícios, Borisov encontrou umagrande quantidade de ídolos. Numa das moradas, achouuma arca com figuras de urso e lobo entalhadas em madeira.“O xamã — escreve Borisov —, depois de ter feitoo exorcismo, colocou-os em sua arca para que eles jamaisaparecessem na tundra”. 10 “As impressões que eutive como artista e como viajante por terras desconhecidas,convivendo com alguns nativos, ficaram no fundode minha alma”. 11Essas palavras de Borisov poderiam ser confirmadaspor muitos artistas que também tiveram contato com elese sabiam sobre o modo de vida, lendas e crenças dessespovos, que eram mal conhecidos mesmo na Rússia. Umdeles era Konstantin Korovin (1861–1939), famoso retratistae paisagista de orientação impressionista. No fimda década de 1890, ele viajou à Sibéria para fazer umasérie de quadros a serem expostos no pavilhão “Os confinsda Rússia”, da exposição mundial em Paris em 1900.O Norte o deixou pasmo. “As rochas pretas acima eramblocos enormes, como que colocados ali por gigantes, assemelhadosa monstros estranhos (…) eram cobertas demusgos de diferentes cores, de relva verde forte e de manchasescarlate…” 12 — escreveu Korovin em suas recordações.O artista compensou a impossibilidade de expressarsuas emoções somente por meio da pintura com peles deanimais e peixes vivos trazidos a Paris para a exposição“Os confins da Rússia”. Aquela teria sido provavelmenteuma das primeiras instalações artísticas, a atmosfera — ocheiro, os objetos e a cor naturais — foi trazida para as salasde exposição diretamente de seu contexto original.A imprensa russa escreveu muito sobre essa exposiçãoe sobre as expedições com participação de Borisov.As obras executadas pelos artistas durante a expediçãoe as impressões que elas produziram eram muito populares.O público as amava, e elas inspiravam muitos pintoresda época que estavam em busca de novos caminhose novas linguagens artísticas.Wassily Kandinsky, cujos antepassados eram da Sibéria,era muito atento a informações sobre as tradiçõese crenças destas regiões, como também sobre o Norte daRússia, onde ele mesmo estivera. A simplicidade da natureza,do modo de vida e dos hábitos que Kandinskyconhecera no Norte, convenceram-no de que esse estilode vida minimalista, próprio de quem mora em regiõeslongínquas do centro da Rússia, não os privava de emoçõese sentimentos, inerentes a todas as pessoas. A diferençaconsistia apenas no fato de que eles se expressavamde outra maneira ou com outras palavras.Kandinsky dava especial importância ao conceito zyrianode ort (espírito, alma — espíritos bons que povoamo espaço aéreo). Segundo a dedução de Kandinsky, todapessoa tem seu próprio ort, que vem com a pessoa quantheseexpeditions left posterity with a remarkable testimonythat included not only paintings and drawings but also memoirs,tales and correspondence. Alexander Borisov, for example,known as the “first painter of the Arctic”, not only createdmonumental and laconic landscapes of snowbound cliffsand endless expanses but also studied the lifestyle of theSamoyed peoples. 9 Borisov searched out the enormousmounds where the Samoyeds performed their sacrifice rituals.In one native dwelling he discovered a chest with woodenfigures of a wolf and bear inside. “These,” wrote Borisov,“were left by a shaman, who placed the wolf and bear thereafter performing magical incantations so they wouldn’t appearin the tundra.” 10 “The impressions I received from mytime spent among the Samoyeds,” continued Borisov, “left adeep imprint on my soul, both as an artist and a wanderer ofunknown lands.” 11Borisov’s words might have been echoed by many of theother Russian artists who in the 1880s and 90s came into directcontact with the ways, legends and beliefs of native peopleslittle known then even in Russia. One of these artists wasKonstantin Korovin (1861–1939), the celebrated portraitand landscape painter of Impressionist orientation, who setoff for Siberia in the late 1890s to make a series of paintingsfor the Far Regions Pavilion of the 1900 Exposition Universellein Paris. The North produced an overwhelming impressionon Korovin. “There are black cliffs on high, enormousblocks, as if set there by giants. Covered with coloredmoss, with bright green and crimson patches, these blocksresemble bizarre monsters,” 12 wrote the artist in his memoirs.Finding the means of painting alone insufficient to expressthe emotions he’d experienced, Korovin compensated bybringing real animal skins and live fish to the Paris exposition.The result, in which the atmosphere, odors, textures and colorsof the real world were introduced into the exhibitionspace, might be considered one of the world’s first art installations.The Russian press wrote extensively about the Paris exposition,as it did about the expeditions in which Borisov tookpart. Artworks created during expeditions or based on impressionsfrom them were extremely popular then, not just amongthe public but also with artists of the day, who were searchingfor fresh themes and ways to renew the language of art.Kandinsky’s forebears were from Siberia, and he was alwaysopen to new knowledge about the traditions and beliefsof that region as well as the Russian North, where he himselftraveled. Experiencing first-hand the austere natural landscape,simple, even primitive, lifestyle and simple customs ofthe inhabitants of Russia’s remote northern regions, Kandinskybecame convinced that, despite the minimalism of their culture,they lacked none of the sensations and emotions that allpeople experience. The only difference lay in the fact that theyexpressed them differently, using different words.Kandinsky attached special significance to the Zyrian conceptof ort (spirit, soul, kind spirits inhabiting the air), concludingthat every person is endowed with his own ort at birth. 13From that time on, the theme of the soul comes up often inKandinsky’s correspondence and published articles. Discussinghis personal experiences in an 1893 letter to his friendNikolai Kharuzin, the artist describes how his relationshipswith people evolved in childhood and youth. Kandinsky relatesthat he was greatly loved at first as a child but that somethinglater “snapped” and everything changed dramatically.“The pain and enmity I experienced in my family,” Kandinskywrites, “didn’t change me outwardly, but it wounded my soulCamponeses. Anos1890. Fotógrafo desconhecidoImpressão de brometo de prata. Ill.: 18,3 x 23,9Museu Estatal RussoPeasants. 1890s. Unknown PhotographerSilver bromide print. Ill.: 18.3 x 23.9State Russian MuseumPovos samoiedos. Arkhangelsk. Anos 1880Fotógrafo Yakov Leitsinger (1855–1914)Carta aberta. Foto tinto. Ill.: 13,8 x 8,7Museu Estatal RussoMezen Samoyeds. Arkhangelsk Gubernia. 1880sPhotographer Yakov Leitsinger (1855–1914)Open letter. Photo tinto. Ill.: 13.8 x 8.7State Russian MuseumSamoiedos em uma tenda de pele de renaDistrito Pechersky, Arkhangelsk. 1904Fotógrafo Dmitry Rudnev (1879–1932)Carta aberta. Foto tinto. Ill.: 8,7 x 13,8Museu Estatal RussoSamoyeds in a Reindeer Skin TentPechersky District, Arkhangelsk Gubernia. 1904Photographer Dmitry Rudnev (1879–1932)Open letter. Photo tinto. Ill.: 8.7 x 13.8State Russian Museum/13/

<strong>KANDINSKY</strong> NO CONTEXTO DA CULTURA RUSSA DO FIM DO SÉCULO XIX E DO COMEÇO DO SÉCULO XX // <strong>KANDINSKY</strong> IN THE CONTEXT OF TURN-OF-THE-20TH-CENTURY RUSSIAN CULTUREIlya VylkoA entrada para o EstreitoMatochkin de Shar. 1909Óleo sobre tela. 27 x 54,7Recebido em 1930 da State HermitageMuseu Estatal RussoEntrance to the Straitof Matochkin Shar. 1909Oil on canvas. 27 x 54.7Received in 1930 from the State HermitageState Russian MuseumPomors vestindo trajes populares. Anos 1880Fotógrafo Yakov Leitsinger (1855–1914)Impressão de brometo de prataIll.: 15,8 x 22,5Museu Estatal RussoPomors Wearing NationalFolk Costumes. 1880sPhotographer Yakov Leitsinger (1855–1914)Silver bromide printIll.: 15.8 x 22.5State Russian MuseumVasily VereshchaginCabeça de um homem Zyrian. Anos 1890Óleo sobre tela. 39,3 x 29,3Recebeu em 1900 do autorMuseu Estatal RussoHead of a Zyrian Man. 1890sOil on canvas. 39.3 x 29.3Received in 1900 from the artistState Russian Museumdo ela nasce. 13 Desde então, o tema “alma” aparece frequentementeem sua correspondência e em seus artigos.Discutindo com o amigo Nikolai Kharuzin seus própriossentimentos em uma carta de 1893, ele conta sobre seurelacionamento com as pessoas na infância e na juventude.Na infância, segundo escreve Kandinsky, ele foimuito amado, de início, mas depois tudo mudou bruscamente,“rompeu-se”. “Em resposta à dor e à maldadeque eu sentia na família, eu não mudei externamente —escreve Kandinsky –, mas minha alma doía muito”. 14 Omesmo sobre os amigos dos tempos da universidade. “Euacreditava neles e os amava” — escreve Kandinsky aomesmo destinatário. — “Mas soube que aqueles que euconsiderava amigos eram inimigos e vice-versa”. “É precisoacrescentar” — resume Kandinsky — “que nunca nenhum(sublinhado por Kandinsky) de meus amigos adentroua vida íntima de minha alma” 15 (grifo nosso — E. P.).A profunda convicção de Kandinsky de que, tanto navida quanto na arte, a alma, o espiritual, devem prevalecersobre o material, formou sua concepção de mundoainda naquela época, no fim dos anos 1880. O tema doconteúdo interior que gera o sentido da obra de arte torna-se,por um longo tempo, a base de suas reflexõesteóricas e da busca prática de uma nova linguagem artística.Essa aspiração de Kandinsky correspondia plenamenteà concepção de mundo dos artistas russos e europeus,dos poetas e músicos da época do simbolismo.O já mencionado Konstantin Korovin, ponderando sobrea paisagem, escreveu em 1892: “A paisagem não temvalor se é apenas bonita. Nela deve haver a história daalma, ela deve emitir um som que responde aos sentimentosdo coração”. 16O afastamento do naturalismo em prol da apresentaçãoemocional do mundo é um sinal característico demuitas obras do fim do século XIX e do começo do séculoXX. Temas ligados ao milagre e à metamorfose detodo tipo ganharam uma grande popularidade entre ospintores russos no limiar dos séculos XIX e XX e foramassociados tanto ao simbolismo quanto às tradições dofolclore nacional.No início de sua atividade artística, rendeu seu tributoa essa tendência com quadros voltados a temasfolclóricos e à história antiga da Rússia, que são menosconhecidos do que os abstratos. 17 E não estava sozinhonessa paixão.Ainda na década de 1880, Wassily Kandinsky estevepela primeira vez no Norte da Rússia. Essas terras estavamsendo estudadas por Nicholas Roerich, Elena Polenovae os irmãos Viktor e Apollinary Vasnetsov. Assimcomo Kandinsky e seus contemporâneos, eles ouviamhistórias populares desde a infância. Em suas casas eprincipalmente nas aldeias, onde muitos deles passavamo verão, havia muitos objetos de arte popular e ícones.Eram tão familiares que, até o fim do século XIX,não eram vistos como obras de arte.Somente a partir do fim do século XIX, os utensílios,contos, lendas e canções populares começaram a ser reunidose estudados. Elena Polenova, contemporânea deKandinsky, contou que, nas aldeias, transcrevia contosde fadas e fazia ilustrações para elas. Assim, ela “usavao material vivo e não livresco, i.e., fazia mulheres, criançasou velhos contá-las…”. 18 Kandinsky tinha a mesmaaspiração de registrar a versão original, autêntica, quandotomava nota das canções nas aldeias. 19deeply.” 14 He writes much the same way about his universityfriends: “I believed in them and loved them,” writes Kandinskyto Kharuzin. But then he discovered that those he consideredhis friends were enemies, and vice versa. “It must be said,”summed up Kandinsky, “that none of my friends ever enteredthe intimate life of my soul” 15 (underlining Kandinsky’s; hereand elsewhere, italics mine — E. P.).It was back then, in the 1880s, that Kandinsky becamedeeply convinced that the soul and the spiritual must takeprecedence over the material, both in life and art. The ideathat inner content was the artwork’s main raison d’être becamethe main theme of his theoretical meditations and the goal ofhis practical quest for a new artistic language. And in thisKandinsky was in full agreement with other artists, poets andmusicians of the Symbolist age, both in Russia and Europe. Theaforementioned Konstantin Korovin, for example, wrote on thesubject of landscape painting in 1892: “A landscape is worthnothing if it’s merely beautiful. It must contain the story of thesoul, it must be a sound echoing the emotions of the heart.” 16A rejection of naturalism in favor of an emotional expressionof the world was typical for much turn-of-the-20th-centuryart. The themes of miracles, visions and all manner oftransformations acquired wide popularity among Russianartists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, drawing themcloser both to European Symbolism and their own nationalfolk traditions. At the beginning of his creative career, Kandinskypaid enthusiastic tribute to this trend in his works on fairytaleand Russian historical subjects, works less familiar to themuseum-going and reading public than his abstract paintings.17 And this enthusiasm was shared by many other artists.By the time of Kandinsky’s first trip to the Russian North inthe late 1880s, the region had already been explored byNicholas Roerich, Elena Polenova and Viktor and ApollinaryVasnetsov. Just like Kandinsky and his contemporaries, theseartists had been raised on Russian folklore and fairy tales,many of them spending their childhood summers in countryhouses surrounded by folk-art objects and icons. All of thiswas so commonplace that until the end of the 19th centuryno one in Russia seriously regarded any of the various formsof folk art as art.Only then did icons, peasant household objects, fairytales, bylina epics and folk songs begin to become objects ofstudy and collection. Kandinsky’s contemporary Elena Polenovadescribed how she went to villages to record fairy talesfor use in her illustrations: “I used live material, not from books;in other words, I made old peasants, women and children tellme [the stories].” 18 The same desire to preserve the memoryof original, authentic peasant culture inspired Kandinsky totravel to villages and record folk songs. 19A large number of artists, including Dmitry Stelletsky, IvanBilibin, Nicholas Roerich, Mikhail Vrubel and Elena Polenova,were inspired by Old Russian traditions and folk art and createdmany remarkable things (a significant number of whichare in the Lenbachhaus Museum collection in Munich) thatare stylistically and thematically akin to Kandinsky’s earlywork. Undeniably, Kandinsky’s enthusiasm for Old Russiawas merely one episode in his creative biography. But it lefta noticeable mark on his artistic legacy, with the artist returningto fairy-tale subjects at various times in his later career.The sense of wonder, fantasy and irreality that comprises theessence of the fairy tales of all peoples helped many artists,including Kandinsky, free themselves from the oppression ofnaturalism. In Stupeni Kandinsky mentions the Russian fairytales that his aunt knew and read to him as among his strongest/15/

<strong>KANDINSKY</strong> NO CONTEXTO DA CULTURA RUSSA DO FIM DO SÉCULO XIX E DO COMEÇO DO SÉCULO XX // <strong>KANDINSKY</strong> IN THE CONTEXT OF TURN-OF-THE-20TH-CENTURY RUSSIAN CULTUREDmitry Stelletsky, Ivan Bilibin, Nicholas Roerich, MikhailVrubel, Elena Polenova e muitos outros pintores russos,amantes da antiguidade russa, dos hábitos e da arte dopovo, criaram muitas obras notáveis que, por seu estilo etemática, aproximam-se das primeiras obras de Kandinsky,das quais uma parte significativa pertence ao MuseuLenbachhaus (Munique). Esse interesse pela velha Rússiafoi, sem dúvida, apenas um episódio na biografia do pintor.Porém, deixou uma marca notável em sua obra, deforma que, posteriormente, de uma maneira ou outra, elevoltaria aos temas de lendas. Os milagres, o fantástico ea irrealidade que determinam a essência dos contos dequalquer povo ajudaram Kandinsky e muitos outros pintoresa se livrar da pressão do naturalismo. O próprioKandinsky recorda em “Degraus” que as impressõesque mais fortemente o influenciaram, além das da música,foram as das histórias populares russas que suatia lhe contava. 20Além das lendas, Kandinsky, como todos os outros,tinha contato com utensílios e brinquedos de madeira,pintados com cores fortes. Mais tarde, viajando pelo Norte,Kandinsky registrou por escrito canções populares eprovérbios, orações e conjuros, desenhou nos álbuns detalhesdecorativos de casas de madeira, utensílios e objetosdomésticos (Lenbachhaus, Munique). Na mesmaépoca, ele começou a colecionar arte popular, inclusiveícones (particularmente, os de São Jorge), brinquedos,rodas de fiar e os lubok (estampas primitivas). Em 1911,já com uma coleção considerável, Kandinsky, como verdadeirocolecionador, pediu a seu amigo Nikolai Kulbinque achasse para ele mais um tema de lubok “…se possível,bem antigo, primitivo (com serpentes, diabos e bisposetc.)”. 21 Não é por acaso que um lubok aparece penduradona parede do apartamento de Kandinsky, emuma foto publicada frequentemente.Para a Rússia do fim do século XIX e do começo do séculoXX, a atração de Kandinsky pela arte popular nãoera incomum. A onda de interesse pela história nacional,a vida e os costumes dos camponeses, a classe mais numerosado país, abarcou diversas camadas da população.Em grande parte, ela correspondia à atenção doseuropeus aos povos africanos, asiáticos, indianos e outros.Nesse mergulho profundo na antiguidade russa enos diversos gêneros do folclore, formaram-se muitos artistasda vanguarda russa na pintura (Natalia Goncharova,Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin e outros) que estavamna primeira etapa do figurativismo. Kandinsky,que sentiu a influência da arte popular, viva e pitoresca,porém privada de continuidade, talvez tenha tomadoemprestado dela sua essência decorativa, lacônica e expressiva,“sem palavras”. “Frequentemente eu desenhavaesses ornamentos que nunca se perdiam em pormenorese foram feitos com tanta força que o próprio objetoperdia-se neles…”. 22 Provavelmente, justo por causadessas impressões, encarnavam-se minhas posterioresintenções e meus objetivos na arte”. 23Durante alguns anos, Kandinsky procurou um meio deintroduzir o espectador no quadro, para que ele girasse,se diluísse na obra e recebesse uma impressão emocionalíntegra do representado. São bem conhecidas e citadasas linhas do verso “Degraus” nas quais Kandinsky descreveuo momento em que entendeu exatamente comodeveria pintar seus quadros. “Lembro-me muito vivamentecomo eu parei diante desse espetáculo inesperado. Mechildhoodimpressions, the ones that most influenced him inlater life, the other being music. 20In addition to fairy tales, Kandinsky and other artists werealso familiar with various folk art objects in their childhoods,from wooden toys to brightly decorated household utensils.Later, during his travels in the North, Kandinsky recorded folksongs, sayings, prayers and incantations and sketchedkitchenware, household objects and decorative details ofwooden houses (Lenbachhaus, Munich). At that time he alsobegan a folk art collection that included icons (among themicons of St. George), toys, distaffs and lubok pictures. By 1911Kandinsky’s collection was already quite passable, and hisrequest that year for his friend Nikolai Kulbin to find him yetanother lubok subject, one that was “old and primitive, if possible(with snakes, devils, archbishops and so forth)”, 21 revealsthe instincts of a true collector. It’s no accident that onefrequently reproduced photograph of Kandinsky shows himsitting in his apartment with a lubok picture hanging on thewall in the background.Kandinsky’s passion for folk art was not unusual for a Rus -sian at the turn of the 20th century. Various strata of society wereexperiencing a resurgent interest in national history and the lifeand ways of the peasantry, which made up the bulk of the populationthen. To a significant degree, this trend corresponded tothe rising interest among Europeans in the traditions of Africa,India, Asia and other lands. Many Russian avant-garde artists,including Natalia Goncharova, Kazimir Malevich and VladimirTatlin, underwent their creative formation during this wave of enthusiasmfor Old Russia and its diverse folk culture, and their artin this early period remained within the bounds of figurativity.Colorful, rich and largely non-narrative, folk art influencedKandinsky perhaps more than anything else through its decorativeessence, its laconic, inward, “non-verbal” expressiveness.“I repeatedly sketched these ornaments, which never drownedin trivial detail and were painted with such force that the objectitself was dissolved by them,” 22 he wrote, concluding that “itwas perhaps such impressions as these that gave shape to mysubsequent desires and goals in art.” 23For several years Kandinsky sought a way to draw theviewer into a painting, for him to enter it and dissolve withinit, receiving an organic emotional impression from the image.In one well-known and frequently cited passage in Stupeni,Kandinsky describes the moment when he understood exactlyhow he was to paint his works: “I remember vividly how Istopped on the threshold before this unexpected sight. Thetable, counters, closets, cupboards and enormous and imposingoven: everything was covered with colorful, sweepingpainted ornamentation. On the walls hung lubok pictures: asymbolically depicted bogatyr warrior, battles and a song expressedin paints. The krasny ugol 24 was completely coveredwith painted and printed icons… In these extraordinary peasanthouses I encountered the miracle that later became one of the keyelements of my work. Here I learned how to not look at a paintingfrom the outside but to move about within it, to live inside it.” 25Thus the artist described in his own words how the idea ofthe abstract image in his work came into being. And hestressed that the artist can “influence the soul” only with “hisnative means: paint (color) and form, that is, the arrangementand interrelations (motions) of planes and lines”. 26Kandinsky argued that a new artistic language was needed,because “every age has its own inner goal” and its ownnotion of outward beauty. “Therefore,” he continued, “weshouldn’t measure the new beauty now coming into beingwith the old measuring stick of the past.” 27Cesta para fusos de fiar. Século XIXNizhny NovgorodMadeira, pintura em fibra29,7 x 17,4 x 15,2Museu Estatal RussoBast Box for Spindles. 19th centuryNizhny Novgorod GuberniaWood, painting on bast29.7 x 17.4 x 15.2State Russian MuseumRoca de fiar. Meados do século XIXKenozyorskyMadeira entalhada, colorida e pintada101 x 24,5 x 65Museu Estatal RussoDistaff. Mid-19th century. KenozeroWood, chip carving, coloring, painting101 x 24.5 x 65State Russian MuseumRoca de fiar. Meados do século XIXVilarejo Podgornaya, Distrito Totem,Vologda (Verkhovazhye)Madeira entalhada, colorida e pintada95 x 30 x 53Museu Estatal RussoDistaff. Mid-19th centuryPodgornaya Village, Totem District,Vologda Gubernia (Verkhovazhye)Wood, chip carving. 93 x 30 x 53State Russian MuseumRoca de fiar. Meados do século XIXAldeia de Piemonte, Distrito Totem,Província de Vologda (Verkhovazhye)Mestre Kulatov I. A .Madeira entalhada, colorida e pintada95 x 30 x 53Museu Estatal RussoDistaff. Mid-19th centuryPodgornaya Village, Totem District,Vologda Gubernia (Verkhovazhye)Master I. A. KulatovWood, chip carving. 95 x 30 x 53State Russian MuseumDmitry StelletskyDonzelas. 1906Guache e têmpera sobre papel. 65,7 x 102,7Recebido em 1984 da coleçãode B. N. Okunev, LeningradoMuseu Estatal RussoMaidens. 1906Gouache and tempera on paper. 65.7 x 102.7Received in 1984 from the Boris Okunevcollection, LeningradState Russian Museum/17/

<strong>KANDINSKY</strong> NO CONTEXTO DA CULTURA RUSSA DO FIM DO SÉCULO XIX E DO COMEÇO DO SÉCULO XX // <strong>KANDINSKY</strong> IN THE CONTEXT OF TURN-OF-THE-20TH-CENTURY RUSSIAN CULTURECesto. 1920–1930Vilarejo Verkhniaya UftiugaRegião ArkhangelskPintura sobre madeiraAltura: 13; diâmetro: 36,7Museu Estatal Russo“Não repreenda-me querida…”Litografia por Wasilyev. 1884Litografia colorida em papelIll.: 22,8 x 34,6; folha: 34,8 x 44,3Museu Estatal Russo“Do Not Scold Me Dear…”Lithograph by Vasilyev. 1884Colored lithograph on paperIll.: 22.8 x 34.6; sheet: 34.8 x 44.3State Russian MuseumIgreja do século XVIIAldeia ChukhchermaDistrito Kholmogorsk,Arkhangelsk. 1911Fotógrafo N. G. NeverovCarta aberta. Foto tintoIll.: 8,8 x 13,8Museu Estatal Russo17th-century church inChukhcherma VillageKholmogorsk District,Arkhangelsk Gubernia. 1911Photographer N. G. NeverovOpen letter. Photo tintoIll.: 8.8 x 13.8State Russian MuseumBasket. 1920s–1930sKrasnoborsk District,Arkhangelsk OblastWood, paintingHeight: 13; diameter: 36.7State Russian Museum“Adeus” (“Não chore, Não chore…”)Artista desconhecido. 1869Litografia colorida em papelIll.: 24 x 36,7; folha: 34,6 x 45,2Museu Estatal RussoFarewell (“Do Not Cry,Do Not Weep…”)Unknown Engraver. 1869Colored lithograph on paperIll.: 24 x 36.7; sheet: 34.6 x 45.2State Russian MuseumWassily KandinskyDestino. Parede vermelha. 1909Óleo sobre tela. 83 x 116Boris Kustodiev Astrakhan Galeria de Imagens *Fate. Red Wall. 1909Oil on canvas. 83 x 116Boris Kustodiev Picture Gallery, Astrakhan ** Estas obras assinadas por Kandinskynão estão incluídas na exposição.* The marked works by Kandinsky arenot included in the exhibition.sa, bancos, um enorme e altivo forno, armários e prateleiras— tudo decorado com ornamentos multicoloridos espaçados.Estampas nas paredes: um Hércules apresentadosimbolicamente, batalhas, uma canção transmitida pelascores. O canto vermelho 24 da casa, cheio de ícones aóleo e em estampas. Pois foi nessas isbás * incomuns que eume encontrei com aquela maravilha, que posteriormente tornou-seum dos elementos de meus trabalhos. Foi aí que euaprendi a não olhar para os quadros de fora, à distância,mas me mover dentro do quadro, viver nele…”. 25Assim o próprio pintor descreve o surgimento da ideiasobre a imagem abstrata em sua obra. E acentua que “oartista pode influenciar a alma somente com seus meiostradicionais: a tinta (cores), a forma (isto é, com a distribuiçãodos planos e das linhas) e a relação entre eles (omovimento)”. 26Kandinsky explicou a necessidade de uma nova linguagemartística com o argumento de que “cada épocatem sua meta interna e sua beleza externa”. Por isso,“não é preciso medir nossa nova beleza que está nascendocom o velho archin ** do passado”. 27Negando a atitude materialista às artes plásticas,Kandinsky buscava um novo conteúdo (o que), transmitidopor uma nova linguagem artística (como). No caminhodessas buscas, ele reconhecia os méritos das obrasdos simbolistas, impressionistas, de Cézanne, Matisse,pintores de ícones, mestres da arte popular. Mas o atraíaa possibilidade de expressar a “necessidade interior” deuma maneira mais aguda, somente com a cor e a forma.Provavelmente, em suas viagens à Alemanha e retornospara a Rússia, ele estava procurando insistentemente porcorreligionários. Em 1909, em Munique, ele cria a “NovaAssociação Artística” (Neue Künstlervereinigung), e publicacomunicações sobre a atividade da associação em váriosartigos nas revistas russas “Mundo da arte” e “Apollon”.28 Passados dois anos, junto com Franz Marc, elecria a associação artística Der Blaue Reiter (“O CavaleiroAzul”), mais radical ainda nas publicações e exposiçõesda qual também tomam parte os pintores russos (NikolaiKulbin, Vasily Denisov, David e Vladimir Burliuk, NataliaGoncharova, Mikhail Larionov e outros).Nas cartas a seu amigo Nikolai Kulbin, Kandinsky ressaltaque todo esse grupo de pintores de Munique “simpatizacom a Rússia e considera a arte russa próxima aeles”. 29 Na associação “O Cavaleiro Azul”, criada naAlemanha, e em várias associações russas do começo doséculo XX (“Valete de Ouros”, “Salão de Izdebsky” e outros),o espírito do internacionalismo era um dos princípiosdos organizadores. Além das obras de arte, os públicosrusso e alemão podiam, pelos catálogos, conheceros conceitos teóricos dos artistas contemporâneos. O artigode Kandinsky “A forma e o conteúdo” foi publicadojustamente no catálogo da associação “Salão de Izdebsky”(mais tarde, esse artigo fez parte de seu tratado “DoEspiritual na Arte”). Numa das exposições do “Salão”,foram mostradas 53 obras de Kandinsky. Ela foi praticamentesua primeira exposição individual. Do “Salão” faziamparte obras de Alexej von Jawlensky, GabrieleMünter e Franz Marc, membros do círculo de Munique.Quase no mesmo tempo, na revista Almanach Der BlaueReiter, foram publicados artigos de David Burliuk (“Os sel-*Casa rústica característica da região da Rússia.**Antiga medida russa equivalente a 0,71 m. (N. da T.)Rejecting the materialistic approach to art, which depictsnature as it appears, Kandinsky sought a new content (“what”)and a new artistic language to express it with (“how”). Herecognized that the Symbolists, the Expressionists, Cézanne,Matisse, folk artists and icon painters had all achieved this intheir own way. But he was attracted by the possibility of aneven more vivid expression of “inner necessity”, through theuse of color and form alone. For this reason, apparently,Kandinsky stubbornly sought others who thought as he did ashe traveled back and forth between Russia and Germany.Gabriele MünterIgreja em vilarejo. Início dos anos 1910. Óleo sobre tela. 45 x 62Coleção privada, AlemanhaVillage Church. Early 1910s. Oil on canvas. 45 x 62Private collection, GermanyGabriele MünterFloresta. Início dos anos 1910. Óleo sobre tela. 30 x 40Coleção privada, AlemanhaForest . Early 1910s. Oil on canvas. 30 x 40Private collection, GermanyIn 1909 he creates the Neue Künstlervereinigung (New Artist’sAssociation) in Munich and writes several articles in the Rus -sian journals World of Art and Apollon describing its activities. 28Two years later he and Franz Marc create an even more radicalalliance, Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), whose publicationsand exhibitions include, among others, works by Rus -sian artists Nikolai Kulbin, Vasily Denisov, David and Vla dimirBurliuk, Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov.Writing to his friend Nikolai Kulbin, Kandinsky emphasizesthat the entire art circle in Munich “is drawn to Russia in generaland considers Russian art kindred in spirit”. 29 One of theprinciples upheld by Der Blaue Reiter’s organizers in Ger-/19/

<strong>KANDINSKY</strong> NO CONTEXTO DA CULTURA RUSSA DO FIM DO SÉCULO XIX E DO COMEÇO DO SÉCULO XX // <strong>KANDINSKY</strong> IN THE CONTEXT OF TURN-OF-THE-20TH-CENTURY RUSSIAN CULTUREvagens da Rússia”), Nikolai Kulbin (“A música livre”),Thomas de Hartmann (“Sobre a anarquia na música”). Daexposição de “O Cavaleiro Azul” participaram os amigosrussos de Kandinsky (David e Vladimir Burliuk, Vasily Denisov,Serafim Sudbinin, Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov,Vladimir Bekhteev, Nikolai Kulbin e outros).Essa atitude internacional resultou na rapidez e na qualidadedo desenvolvimento da vanguarda tanto europeiacomo russa. Os pintores russos convidados a participar de“O Cavaleiro Azul”correspondiam às ideias de Kandinskysobre os estudos artísticos daquela época. Suas obras aindaestavam nos moldes da arte figurativa, mas saíam doslimites das normas acadêmicas do realismo. Frequentemente,em suas telas, o objeto “se diluía” e sua cor e formatornavam-se os protagonistas.O relacionamento entre músicos, escritores e pintoresno início do século XX também teve certa importância nabusca por novas soluções. Na Rússia, esse relacionamentosempre foi bastante estreito e proveitoso. Mas, no iníciodo século XX, a influência da vanguarda musical tornaseespecialmente evidente.A natureza imaterial da música permitiu que compositoresextrapolassem limites e atingissem a chamadaquarta dimensão: o tempo. Permitiu também “quebrar”o espaço do quadro, fragmentar os objetos, dar às cores,formas e desenho um sentido independente — algo característicodos futuristas, cubistas, expressionistas e orfeístas—, e mudou muito o conceito de tempo nas artesplásticas. O ritmo, a velocidade, a dinâmica, a simultaneidade,que correspondem à dissonância e à polifoniana terminologia musical, e que estavam presentes nasobras futuristas, atestavam uma ligação profunda entreas técnicas usadas nas artes plásticas e na música.Wassily Kandinsky, que estava seguindo a experiênciados músicos e dos pintores do começo do séculoXX, foi mais longe aproximando ao máximo as associaçõesfigurativas. O que serviu de impulso para a reviravoltana consciência de Kandinsky foi, entre outrosfatores, a ópera “Lohengrin” de Wagner. Ouvindo aópera, Kandinsky associou a música com os poentesem Moscou, quando as cores se inflamam uma atrás daoutra, antes de transformar a cidade numa mancha vermelhaque soa como o acorde final, um “fortíssimo deuma orquestra enorme”. “Ficou bem claro para mimque (…) a pintura é capaz de revelar as mesmas forçasque a música”. 30Desde então, Kandinsky esteve à procura do “som colorido”,força da ação direta da cor nos sentimentos humanos,a capacidade da pintura de tocar a alma. Fazendoparalelo entre a música e a pintura, Kandinsky escreveno artigo “Do Espiritual na Arte”: “A cor é a tecla. O olhar,o martelo. A alma, o piano com inúmeras cordas”. 31 Nãofoi por acaso que entre os pintores russos com quem Kandinskytrabalhava ou mantinha relacionamento haviamuitos músicos (Nikolai Kulbin, Mikhail Matyushin, VladimirBaranoff-Rossiné, Vasily Denisov e outros).No início do século XX, esse grande interesse pelosefeitos da cor e da música também moviam AlexanderSkriabin e Vladimir Baranoff-Rossiné, que criou um instrumentoespecial * — atualmente, no Centro Pompidou.O pintor e compositor Mikhail Matyushin também dava*O piano optofônico, um instrumento eletrônico ótico que simultaneamente gerasons e projeta luzes coloridas e texturas.many was the international makeup of its participants. This,incidentally, was also true for several early 20th-century Rus -sian alliances, including the Jack of Diamonds and IzdebskySalons. In addition to artworks, these alliances’ exhibition cataloguesprovided Russian and German readers with introductionsto the theoretical views of contemporary artists. For example,Kandinsky’s article “Content and Form” (later includedin his treatise “On the Spiritual in Art”) was first publishedin an Izdebsky Salon catalogue. Altogether, Kandinskyshowed fifty-three of his works at the 2nd Salons, making themin essence his first solo exhibitions. The catalogue’s cover wasdesigned by him as well. The Izdebsky Salons also presentedworks by Munich circle members Alexej von Jawlensky,Gabriele Münter and Franz Marc.Around the same time, the Blaue Reiter almanac published articlesby David Burliuk (“Wild Russians”), Nikolai Kulbin (“FreeMusic”) and Thomas de Hartmann (“On Anarchy in Music”).Among Der Blaue Reiter’s exhibiting participants were many ofKandinsky’s Russian friends, including David and VladimirBurliuk, Vasily Denisov, Serafim Sudbinin, Natalia Goncharova,Mikhail Larionov, Vladimir Bekhteev and Nikolai Kulbin.Such an international approach had an undoubtedly beneficialeffect on the Russian and European avant-garde’s intensityand quality of development. The works of Der BlaueReiter’s Russian participants conformed to Kandinsky’s ideasat the time about contemporary art’s proper line of evolution.While remaining within the bounds of figurativity, theynonetheless violated traditional academic and realist norms.Objects in the works often “melted away”, allowing pure colorand form to come to the fore and express meaning.Relationships among musicians, writers and artists playeda considerable role in furthering the new art’s developmentat the dawn of the 20th century. In Russia, such relationshipshad always been quite close and productive. But in the early20th century, avant-garde music’s influence on the visual artsbecame especially noticeable.Music’s non-material essence freed composers from thelimitations imposed by space, allowing them to master the socalledfourth dimension, time. Futurism, Cubism, Expressionismand Orphism greatly altered accepted notions of time in thevisual arts, fragmenting objects, violating the painting’s unifiedspace and endowing color, form and design with independentmeaning. The musical qualities present in Futuristworks — rhythm, tempo, dynamics, simultaneity, dissonanceand polyphony — revealed a deep connection between musicand the visual arts.Building on the experience of turn-of-the-20th-centuryartists and musicians, Wassily Kandinsky went further, bringingvisual and musical associations into maximally close contact.One of the events that helped spark the revolution inKandinsky’s consciousness was his first hearing of Wagner’sopera Lohengrin in 1898. The music aroused associations inthe artist’s mind with sunsets in Moscow, when colors flare upone after another, turning the city into a giant red spot thatsounds like a final chord, a “fortissimo of an enormous orchestra”,in his words. “It became perfectly clear to me that … artwas capable of manifesting the same forces as music,” theartist concluded. 30From that time onwards, Kandinsky actively seeks to embodyin his painting the quality of “color hearing”, i. e. color’spower to directly influence the emotions, to “touch the soul”.In the treatise “On the Spiritual in Art” he draws an analogybetween music and painting: “Color is the piano key. The eyeis the hammer. The soul is the piano itself with its manyWassily KandinskyXilogravuras. Frontispício.Cópia colorida. 32 x 32Arnold Schönberg Center, VienaXylographies. Title pageColored copy. 32 x 32Arnold Schönberg Center, ViennaCatálogo para exposição do “Salão 2”em Odessa. Livro 4, 1910–1911Com comentários manuscritos de Wassily KandinskyFac-símile. 27,2 x 23,3Arnold Schönberg Center, VienaCatalogue for the 2nd Salons internationalexhibition in Odessa. Book 4, 1910–1911With handwritten comments from Wassily KandinskyFacsimile. 27.2 x 23.3Arnold Schönberg Center, ViennaCatálogo da exposição do grupo“Cavaleiro Azul”. Munique, 1911–191215 x 12Arnold Schönberg Center, VienaCatalogue for Der Blaue Reiterexhibition. Munich, 1911–191215 x 12Arnold Schönberg Center, ViennaWassily KandinskyDo Espiritual na ArteMunique, 1912Com dedicatória de Kandinsky21 x 18,3Arnold Schönberg Center, VienaConcerning the Spiritualin Art. Munich, 1912With an inscriptionby Wassily Kandinsky21 x 18.3Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna/21/

<strong>KANDINSKY</strong> NO CONTEXTO DA CULTURA RUSSA DO FIM DO SÉCULO XIX E DO COMEÇO DO SÉCULO XX // <strong>KANDINSKY</strong> IN THE CONTEXT OF TURN-OF-THE-20TH-CENTURY RUSSIAN CULTUREWassily KandinskySul. 1917Óleo sobre tela. 72 x 101Boris Kustodiev AstrakhanGaleria de Imagens *South. 1917Oil on canvas. 72 x 101Boris Kustodiev PictureGallery, Astrakhan *Wassily KandinskySonoridades. 1913Primeira edição limitada28,6 x 28,6 x 1,5;caixa: 29,5 x 29,5 x 2,5Arnold Schönberg Center, VienaSounds. 1913Limited first edition28.6 x 28.6 x 1.5;box: 29.5 x 29.5 x 2.5Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna© ADAGP, Paris, 2011muita atenção à correlação da cor e do som. Foi em suaópera bufa “Vitória Sobre o Sol” que o Quadrado Negrode Malevich apareceu pela primeira vez.Um dos amigos próximos de Kandinsky era Thomasde Hartmann, irmão de Viktor Hartmann, autor dos desenhosque deixaram Modest Mussorgsky encantado eque serviram de tema para sua obra-prima “Quadros deuma exposição”. É notável que Kandinsky, autor do artigo“Quadros de uma exposição de Modest Mussorgsky”,tenha sido convidado por Thomas de Hartmann para sero cenógrafo do balé homônimo. 32Anteriormente, em 1911, junto com Alexej von Jawlensky,Marianne von Werefkin e Gabriele Münter, Kandinskyesteve em Munique, onde assistiu ao concerto deArnold Schönberg. Foram executados três peças de pianoe dois quartetos de corda. Kandinsky ficou comovido coma ordem musical atonal, alógica, encontrada por Schönberg.O pintor escreveu ao compositor uma carta e a envioujunto com uma pasta de gravuras. Desde então, tornaram-seamigos. 33O caminho da dissonância confirma que as buscas deKandinsky na pintura estavam na direção certa. Kandinskytransformou os sentimentos e as impressões que tevedo concerto de Schönberg no quadro “Impressão III(Concerto)”.Já no começo de 1910, Schönberg, também pintor, comose verificou, torna-se a figura mais importante paraKandinsky — aliás, Kandinsky para Schönberg também.No catálogo da exposição do “Salão de Izdebsky”, poriniciativa de Kandinsky, foi publicado pela primeira vezo artigo “Paralelos nas oitavas e quintas”, de Schönberg.Em dezembro de 1912, Kandinsky convida Schönberg aSão Petersburgo para presenciar a noite de “Concertosde Zilotti”, onde seria tocado o poema sinfônico “Pellease Melizanda”, de Debussy, sob a regência do autor. 34E justamente Kandinsky escreve um artigo especial dedicadoà obra pictórica de Schönberg. 35 Nas telas docompositor, ele destaca a presença do elemento principalpara a arte: “o reflexo das observações e emoções no terrenodos sentimentos”. 36 Confirmando as reclamações decríticos e de espectadores referentes aos quadros incomuns,estranhos para eles, Kandinsky explicou sua preferênciadizendo que, para ele, toda a obra pictórica deSchönberg é uma conversa na língua adequada ao estadointerior do autor. Assim como na música, consideraKandinsky, Schönberg despreza tudo o que é excesso.“Eu preferiria — escreve Kandinsky — chamar a pinturade Schönberg somente de pintura”. 37 E para concluir o artigosobre o compositor, Kandinsky apresenta seu princípioadotado em 1911: “Que o destino nos permita darouvidos ao que diz a alma”. 38O estado da alma, expresso com tintas, acompanhacada obra criada por Kandinsky no século XX. Kandinskyprovou que com a cor e a forma, com a combinação delas,com o ritmo e com a correlação, é possível, de maneiraadequada, transmitir o estado de espírito e as emoçõestanto daquilo que vemos quanto do que está guardadoprofundamente dentro do homem. Já no começodos anos 1910, Kandinsky comprovou suas reflexões teóricascom alguns quadros abstratos. Num deles, São Jorge(1911), atualmente no Museu Russo, está apresentadona tela não como a figura tradicional de cavaleiro matandoo dragão. A energia do movimento do pincel, expressapor manchas de cor e um triângulo comprido e agudo,strings.” 31 It’s no accident that many of the Russian artistswhom Kandinsky knew or productively collaborated withwere also musicians, including Nikolai Kulbin, MikhailMatyushin, Vladimir Baranoff-Rossiné and Vasily Denisov.One early 20th-century figure with a passion for color-musiceffects was the composer Alexander Scriabin. Another wasthe painter Vladimir Baranoff-Rossiné, who created a specialinstrument now housed in the Centre Pompidou collection.Artist and composer Mikhail Matyushin, author of the operaVictory over the Sun (where Kazimir Malevich’s Black Squaremade its debut), also devoted much attention to the relationshipbetween sound and color.Among Kandinsky’s close friends was the composerThomas de Hartmann, nephew of the artist Viktor Hartmannwhose paintings had captured Modest Mussorgsky’s imaginationand inspired the creation of his musical masterpiecePictures at an Exhibition. In a curious twist, Kandinsky, whowrote an article entitled “Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at anExhibition”, was later hired by Thomas de Hartmann as a decoratorfor the ballet by the same name. 32Somewhat earlier, in January 1911, Kandinsky, togetherwith Alexej von Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin andGabriele Münter, attended a concert in Munich at which twostring quartets and three piano pieces by Arnold Schönbergwere performed. Overwhelmed by Schönberg’s atonal, alogicalmusical harmonies, Kandinsky sent the composer a letterand an envelope with etchings. This event marked the beginningof their friendship. 33Schönberg’s orientation towards dissonance in his musicconvinced Kandinsky of the validity of his own explorationsin art, and he embodied the emotions he’d experienced atthe concert in the painting Impression III (Concert).Schönberg, who turned out to be an artist himself, becamea highly important figure for Kandinsky in the 1910s, as didKandinsky for Schönberg. On Kandinsky’s initiative, Schönberg’sarticle “Parallel Octaves and Fifths” was published forthe first time in the exhibition catalogue of Vladimir Izdebsky’s1911 Salon. In December 1912 Kandinsky invited Schönbergto Petersburg to participate in a Siloti Concerts evening,where the composer led a performance of his symphonic poemPelleas und Melisande. 34Finally, Kandinsky devoted an entire article to Schönberg’spaintings, 35 which in his view possessed what he consideredmost important in art: “an emotionally grounded reflectionof observation and experience”. 36 Kandinsky counteredthe objections of critics and viewers regarding Schönberg’sunusual artworks with the explanation that each of them, inhis view, was a dialogue in a language fully adequate to thecreator’s inner state. In Kandinsky’s judgment, Schönbergshunned all excess in his paintings, just as he did in his music.“I’m inclined to call Schönberg’s painting solely painting,” 37he wrote. Kandinsky concluded his article about the composerwith a precept he’d first voiced in 1911: “May ‘fate’ neverallow our inner ear to turn away from the lips of the soul”. 38Kandinsky’s entire 20th-century oeuvre is an expressionof the state of the artist’s soul in paints. Kandinsky proved thatcolor and form alone — their combinations, rhythms and interrelationships— were sufficient to express both moods andexperiences received from the visible world and emotions hiddendeep within the soul. By the early 1910s the artist hadalready confirmed his theoretical ideas with several non-objectivepaintings. One of them, St. George (1911, State RussianMuseum), represents its title subject on canvas, but not as atraditional figurative depiction of a horseman killing a dragon./23/

<strong>KANDINSKY</strong> NO CONTEXTO DA CULTURA RUSSA DO FIM DO SÉCULO XIX E DO COMEÇO DO SÉCULO XX // <strong>KANDINSKY</strong> IN THE CONTEXT OF TURN-OF-THE-20TH-CENTURY RUSSIAN CULTUREque toca num certo ponto na parte inferior da composição— eis a encarnação do famoso tema em ritmo e cor.O ano 1911, quando foi pintado o quadro “São Jorge”,foi o período da formação definitiva do conceito de‘abstração’ nas artes na consciência de Kandinsky. Masa meta principal do artista não era a abstração em si. Emsuas obras chamadas abstratas, aparecem cúpulas deigrejas, animais, árvores, contornos gerais de sua queridaMoscou ou de alguma outra cidade fantástica.As obras de Kandinsky entre 1910–1920 são o resumode impressões de muitos anos, de experiências e reflexões.Indo da Rússia para a Alemanha e viajando poroutros países, Kandinsky afinava seu “ouvido pictórico”.Mas seu principal achado, o que ele descobriu e entendeudefinitivamente, foi que os sentimentos e as emoções, expressaspelas cores, determinam a força e o efeito daobra artística produzidos no espectador. Como muitos artistas,ele tinha o dom do pressentimento e, em muitasobras, expressou o clima no qual viviam ele e a humanidadeinteira daquela época. Em 1911, sentindo a aproximaçãode acontecimentos trágicos, Kandinsky escrevia sobre“o tempo de um terrível vácuo e desolação”. 39 Suasobras abstratas da década de 1910 e do começo da décadade 1920 expressam em cores justamente as emoçõesligadas com os horrores da Primeira Guerra Mundial e desuas consequências, que foram a revolução e a guerra civilna Rússia. “A arte” — escrevia ele — “é o auge exclusivamenteda área dos sentimentos e não do raciocínio” 40 .O espetáculo de cores e de formas nas telas de Kandinsky,no qual prevalece ora o alegre vermelho, ora otranquilo cinza-azulado ou outra gama de cores inscritano ritmo da composição, é sempre emocional.As emoções e os sentimentos nos quais se baseiam osquadros do pintor são “lidos” pelos espectadores. Ampliampara eles o espectro das possibilidades das artesplásticas, que não se limita à representação figurativa domundo. A arte de Kandinsky, que tem suas raízes na culturarussa, é uma das tendências em refletir o mundo pormeios abstratos, página importantíssima na história davanguarda russa, juntamente com as obras de seus contemporâneos— Kazimir Malevich, Olga Rozanova, PávelFilónov, Lyubov Popova, Alexandra Ekster e outros.Instead, the well-known subject is embodied in pure color andrhythm: in the long, sharp triangle with its apex near the bottomof the composition and patches of color infused with theenergy of bold brushstrokes.By 1911, the year of St. George’s creation, Kandinsky’s notionof abstraction in art had completely formed in his creativeconsciousness. But the artist’s main goal was not abstractionper se. In his so-called abstract works we often see elementsof the objective world, be it a church dome, trees, some sortof animal, or the general outline of a fairy-tale city or theartist’s beloved Moscow.Kandinsky’s works from the 1910s and 1920s represent asummation of many years of impressions, experiences and contemplation.While living between Russia and Germany andtraveling in other countries, Kandinsky naturally honed and perfectedhis “painter’s ear”. But most importantly, he’d come tothe firm understanding that an artwork’s force and influence onthe viewer depend on the artist’s ability to express his feelingsand emotions through color. Like many artists, Kandinsky possessedthe gift of premonition, and many of his works from the1910s and early 1920s express the uneasy state of the age inwhich he and the rest of humanity were living. Foreseeing tragicevents on the horizon, Kandinsky wrote as early as 1911 of “atime of fearful emptiness and despair”, 39 and his abstract worksof the 1910s and early 1920s express in paint those very emotions,soon brought on by the horrors of World War I and theensuing revolutionary events in Russia. “Art,” he wrote, “is a livingsummit exclusively in the realm of feeling, not the mind.” 40Every painting by Kandinsky is emotional in its colorful andplastic enchantment. Whether a joyful red predominates in it,or a calmer grayish-blue reigns supreme, or pink or some othercolor of the spectrum waxes triumphant, each color is alwayspainted in its corresponding compositional rhythm. The personalfeelings and moods underlying the artist’s paintings can be“read” by viewers, thus widening their understanding of visualart’s possibilities, which go beyond a mere figurative embodimentof the world. Rooted in Russian culture, Kandinsky’s artrepresents a particular approach to the reflection of realitythrough abstract means. Along with the work of his contemporariesKazimir Malevich, Olga Rozanova, Pavel Filonov, LyubovPopova, Alexandra Ekster and others, it constitutes an importantchapter in the history of Russian avant-garde art.Wassily KandinskyCrista azul. 1917Óleo sobre tela. 133 x 104Embaixo, à esquerda: K 17Recebido em 1920 por intermédiodo Comissariado de Educaçãodo Povo, MoscouMuseu Estatal Russo */25/Blue Crest. 1917Oil on canvas. 133 x 104Bottom left: K 17Received in 1920 viaNarkompros, MoscowState Russian Museum *