Intelligence

The Illusory Theory of Multiple Intelligences

Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences has never been validated.

Posted November 23, 2013 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Many people find the idea that there are many different types of intelligence very appealing. Howard Gardner disparages IQ tests as having limited relevance to real life and argued that there may be as many as eight different kinds of intelligence that apply in diverse areas of human functioning.[1] Gardner’s claims are very similar to those made about “emotional intelligence” being a special kind of intelligence distinct from IQ that may even be more important for success in life than traditional “academic” intelligence. Although Gardner’s claims have become popular with educators, very little research has been done to establish the validity of his theory. The few studies that have been done do not actually support the idea that there are many different kinds of “intelligence” operating separately from each other. Although there certainly are important abilities outside of what IQ tests measure, referring to each one as a special kind of “intelligence” has little scientific support and doing so may only create needless confusion.

A very attractive theory, but does it have any substance?

General intelligence versus multiple intelligences

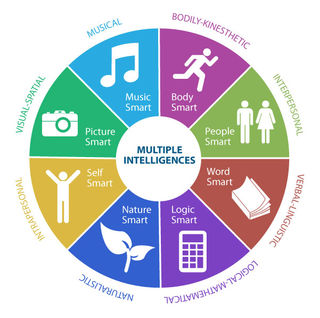

According to mainstream intelligence research, there exists a broad form of mental ability known as “general” intelligence that underlies a wide range of narrower, more specific abilities. IQ tests are intended to provide a measure of this broad general ability, as well as some of the specific ones. Howard Gardner objected to the idea of general intelligence, arguing instead that IQ tests actually measure distinctly narrow academic skills and denied that there is a single general ability that cuts across many different domains. Instead, he argued that there are separate domains of ability that deserve to be called “intelligences” in their own right, and that ability in one domain is unrelated to ability in other domains. Specifically, he argued that IQ tests measure linguistic/verbal and logical/mathematical intelligences, which happen to be valued in schools. The other domains of intelligence he claimed were musical, bodily-kinesthetic (skill in using the body to solve problems), spatial, interpersonal (understanding other people), intrapersonal (ability to understand oneself and regulate one’s life effectively), and naturalistic (recognising different kinds of plants and animals in one’s environment). He also considered, but finally rejected the existence of two further kinds of intelligence: spiritual (understanding the sacred) and existential (understanding one’s place in the universe). These latter two did not meet his rather liberal criteria for an “intelligence”, “biological potential to process information that can be activated in a cultural setting to solve problems or create products that are of value in a culture” (Furnham, 2009).

Sounds nice, but just how much support does the theory have?

The idea that there are multiple independent kinds of intelligence appeals to egalitarian sentiments because it implies that anyone can be “intelligent” in some way or another, even if they are not lucky enough to possess a high IQ (Visser, Ashton, & Vernon, 2006a). This egalitarian view was expressed in an article by Dr Bernard Luskin. He suggested that the theory is accepted by the self-esteem movement, because according to this view no-one is actually "smarter" than anyone else, just different. This all sounds warm and fuzzy, but making people feel good is not an index of scientific validity. Dr. Luskin correctly states that IQ tests are reasonably accurate at predicting how well a person will do at certain school subjects, but they do not gauge a person’s “artistic, environmental and emotional abilities.” Since they were not designed to measure these latter things, this is not controversial. However, there is considerable evidence that IQ tests predict more than just school performance (Visser, Ashton, & Vernon, 2006b) but I will let that pass. What I take issue with here is his incredible assertion that “Today, the concept of multiple intelligences is widely acknowledged.” He makes additional statements about “wide agreement” about Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences, and that it is “widely accepted.” Just who exactly acknowledges, agrees with and accepts the theory is not made clear though. In fact, it is fair to say that among academic scholars who study intelligence there is very little acceptance of Gardner’s theory due to a lack of empirical evidence for it. A critical review of the topic by Lynn Waterhouse in 2006 found no published studies at all that supported the validity of the theory. Even though Gardner first made his theory public in 1983, the first empirical study to test the theory was not published until 23 years later (Visser, et al., 2006a) and the results were not supportive. Multiple intelligences theory can hardly be described as scientifically generative.

Can multiple intelligences be tested?

Dr. Luskin notes that the different types of “intelligence” proposed by Gardner are hard to measure and difficult to assess. Some of the proposed intelligences, such as interpersonal and intrapersonal, are difficult to even define clearly. Gardner himself has declined to specify what he thinks the components of the various intelligences might be or how these might be measured and has only provided nebulous descriptions of them (Waterhouse, 2006a, 2006b). If no-one is really sure what these supposed “intelligences” really are or how to assess them, then generating scientific support for them would appear to be quite difficult. This might go some way to explain the dearth of empirical research on this topic. However, I am aware of at least two studies (Furnham, 2009; Visser, et al., 2006a) that made preliminary attempts at creating operational definitions of these intelligences and developing tests to assess them. As I will show, neither one provided much support for Gardner’s theory.

Trait vs. ability approaches

Since Gardner has not exactly been forthcoming with guidelines on how to assess his proposed intelligences, researchers have had to improvise. As noted earlier, proponents of “emotional intelligence” have claimed that it is something distinct from existing concepts of general intelligence and have actually attempted to develop ways of assessing a person’s “EQ” as opposed to IQ. These methods have taken either a “trait” or an “ability” approach, and the two studies on multiple intelligences that I will look at have adopted each of these approaches respectively. The trait approach is based on asking people to self-estimate their own skill in a given area. This is based on the theory that people mostly have a fairly good idea of how skilled they really are in many areas of life. Even though this might sound a bit naïve, it turns out for example, that when people are asked to self-estimate their general intelligence, they usually give reasonably accurate answers (Furnham, 2009). The ability approach, on the other hand, gives people tests with right or wrong answers and scores them on the accuracy of their results. Traditional IQ tests use this latter approach. Developing an “objective” measure of emotional intelligence poses special challenges, and I have highlighted some of these in a previous post. Similarly, developing tests for some of the ill-defined abilities that Gardner refers to has its own problems. However, if the attempt is not made, the theory cannot be validated.

A pattern that seems to emerge from research on emotional intelligence is that “trait” measures of it tend to be highly correlated with existing measures of personality traits, such as the Big Five, while ability measures tend to be correlated with measures of general intelligence. The latter finding undermines the claim that EQ is distinct from IQ. If “emotional intelligence” can be understood largely in terms of existing concepts of personality and general intelligence, then it is doubtful that the concept adds anything new to our understanding (Schulte, Ree, & Carretta, 2004). A similar pattern of results emerges from the two studies on multiple intelligence that I will review next.

Intelligent personalities?

Furnham (2009) examined a self-report measure of multiple intelligences[2] and its pattern of correlations with a measure of the Big Five personality traits. One striking result was that the eight “intelligences” were highly intercorrelated with each other, contrary to the theory that they are all supposed to represent separate and unrelated domains. In fact, each one was positively correlated with at least four others, and naturalistic intelligence was positively correlated with all seven others. This would suggest that people who scored themselves highly in one domain also tended to score themselves highly in several others. Furthermore, there were many correlations between the eight intelligences and the Big Five traits: all eight intelligences were correlated with at least one of the Big Five, and each of the Big Five was correlated with two or more of the intelligence scores. Openness to experience and extraversion, in particular, were each correlated with five different intelligence scores respectively (but not all the same ones).

Of course, self-report measures have their limitations, especially for measuring skills. For example, the positive correlation between extraversion and five of the “intelligences” might be due to the fact that extraverted people tend to have a highly positive view of themselves and therefore might think they are naturally good at lots of different things. (Although it is possible they really are as good as they say they are, but this is hard to tell without independent measures.) On the other hand, openness to experience is positively correlated with objective measures of general intelligence and of knowledge, so the positive correlations between openness to experience and five of the “intelligences” in Furnham’s study make sense.

Separate abilities from general intelligence or not?

Gardner’s various intelligences are supposed to reflect specific abilities, so Visser et al. (2006) developed a set of ability tests, two for each of the proposed eight intelligences. The authors attempted to assess whether these ability measures were independent of a measure of general intelligence and of each other. Gardner has argued that apparent positive correlations between tests of diverse mental abilities occur because most of these tests are language-based, so they all involve a common core of linguistic intelligence to complete them.[3] To overcome this objection, the authors used non-verbal measures of the non- linguistic intelligences. If Gardner’s theory that the eight types of intelligence are largely independent of each other were true, then the results for each domain should not be highly correlated with each other. However, this did not turn out to be the case. Many of the tests, particularly those measuring some form of cognitive ability, were highly positively correlated with each other. Additionally, most of the ability tests had positive correlations with general intelligence. The exceptions were the tests of musical and bodily-kinesthetic intelligence, which are non-cognitive abilities, and one of the tests of intrapersonal intelligence. The authors concluded that the reason that the tests involving cognitive ability were positively correlated with general intelligence is because they share a common core of reasoning ability. Hence there seems to be a general form of reasoning ability that is applicable across a wide range of ability domains, including linguistic, spatial, logical/mathematical, naturalistic, and to a lesser extent interpersonal abilities. This contradicts Gardner’s assertion that ability in each of these domains is largely separate from ability in the other domains. However, it is consistent with the idea that a broad form of mental ability underlies more specific abilities to a greater or lesser extent.

The authors concluded that Multiple Intelligences theory does not seem to provide any new information beyond that provided by more traditional measures of mental ability. Hence, trying to incorporate Gardner’s theory into educational contexts seems unjustified. Waterhouse (2006b) also expressed scepticism about the value of applying a theory that has not been validated in education, particularly when one of the aims of education is supposed to be to impart up-to-date and accurate knowledge.

Intelligences or skills?

These two research studies do not support the specifics of Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences. Of course, this does not mean that non-cognitive abilities apart from general intelligence are unimportant. There is abundant evidence that personal qualities, such as motivation and social skills, matter a great deal to one’s success in life, and I don't think anyone is really saying otherwise. What is questionable though is describing any talent or ability that happens to be regarded as important as a distinct “intelligence”. We already use the word “skill” to describe how well a person is able to apply their abilities and knowledge in a given area of life. Most people are capable of developing a variety of different skills, but this does not necessarily mean they require a different kind of “intelligence” for each one, so using the term this way is simply arbitrary and confusing (Locke, 2005). Similarly, most people would acknowledge that people can be “smart” in the sense of exercising good judgment and decision making even if they do not have a particularly high IQ. Vice versa, high IQ people can easily make poor decisions, e.g. when emotions or self-interest cloud their reasoning. Again we already have a word for this capacity for good judgment: wisdom. However, I don't think many people would agree that everyone is equally wise. Perhaps there are special abilities that deserve to be called “intelligences” in their own right that have not yet been identified. However, there is no scientific justification for simply inventing special kinds of “intelligence” without evidence just so people can feel good about themselves.

In conclusion, Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences looks to be a confused and nebulous set of claims that have not been empirically validated. Many of Gardner’s proposed “intelligences” appear to be explainable in terms of existing concepts of personality and general intelligence, so the theory does not really offer anything new. Additionally, some of the proposed “intelligences” are poorly defined (particularly intrapersonal) and others (e.g. musical) may be more usefully thought of as skills or talents. The popularity of Gardner’s theories in educational contexts may reflect its sentimental and intuitive appeal but is not founded on any scientific evidence for the validity of the concept.

Other posts discussing intelligence-related topics:

References

[1] Gardner has changed his mind a number of times about the exact number of intelligences over the years, but for convenience, I will consider eight in this article as these are the ones that have been researched.

[2] This measure was originally published in a book written for a lay audience called What’s Your IQ? by Nathan Haselbrauer, published by Barnes and Noble Books.

[3] Gardner is not correct. IQ tests have incorporated non-verbal subtests since the 1930s.

Furnham, A. (2009). The Validity of a New, Self-report Measure of Multiple Intelligence. Current Psychology, 28(4), 225-239. doi: 10.1007/s12144-009-9064-z

Locke, E. A. (2005). Why emotional intelligence is an invalid concept. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 425-431. doi: 10.1002/job.318

Schulte, M. J., Ree, M. J., & Carretta, T. R. (2004). Emotional intelligence: not much more than g and personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(5), 1059-1068. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2003.11.014

Visser, B. A., Ashton, M. C., & Vernon, P. A. (2006a). Beyond g: Putting multiple intelligences theory to the test. Intelligence, 34(5), 487-502. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2006.02.004

Visser, B. A., Ashton, M. C., & Vernon, P. A. (2006b). g and the measurement of Multiple Intelligences: A response to Gardner. Intelligence, 34(5), 507-510. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2006.04.006

Waterhouse, L. (2006a). Inadequate Evidence for Multiple Intelligences, Mozart Effect, and Emotional Intelligence Theories. Educational Psychologist, 41(4), 247-255. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep4104_5

Waterhouse, L. (2006b). Multiple Intelligences, the Mozart Effect, and Emotional Intelligence: A Critical Review. Educational Psychologist, 41(4), 207-225. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep4104_1