For the Vitra Design Museum’s 2014 exhibition of Alvar Aalto’s work, curator Jochen Eisenbrand selected the title "Second Nature" to investigate the architect’s influences more carefully. “So much has been said about the connection Aalto’s work has to the natural world that any reference to it is virtually a cliché,” he wrote in the exhibition catalog. “Precisely for this reason, however, it is worth taking a second look at the influences that shaped Aalto’s work, the networks he moved in and his legacy to the next generations of architects.”

"Second Nature" questioned traditional conceptions of Aalto’s role as a critical regionalist who derived new architectural strategies from provincial landscapes. Rather, the exhibition sought to demonstrate that he was equally influenced by his international connections and studies abroad. “As tempting as it is to see the organic forms in Aalto’s architecture, furniture, and glass objects as a direct reflection of the Finnish landscape [such as] its forests and lakes,” Eisenbrand wrote, “the references to nature in Aalto’s oeuvre are far more nuanced, complex, and considered than they may seem to be on the surface.”

This year, the Ateneum Art Museum in Helsinki is hosting a new Aalto retrospective on view through September 24 that further expands our understanding of the architect’s many muses. Entitled "Alvar Aalto: Art and the Modern Form," the exhibition includes significant works by artists that Aalto considered close colleagues and friends, and whose visual interpretations of the changing world shaped his own approaches to architecture and design. Notably, the comprehensive review of Aalto’s work—also curated by Eisenbrand—is part of a multifaceted program celebrating the centenary of Finland’s independence in 1917. The event also honors the semicentennial of Aalto’s first exhibition in the Anteneum, a one-month show held there in 1967. (For that event, Aalto wrote that paintings and sculpture were like “branches of one and the same tree, the trunk of which is architecture.”) By connecting these momentous occasions with the present, "Art and the Modern Form" not only enriches our appreciation of Finland’s most famous architect but also reminds us of important sources of inspiration for today’s architecture.

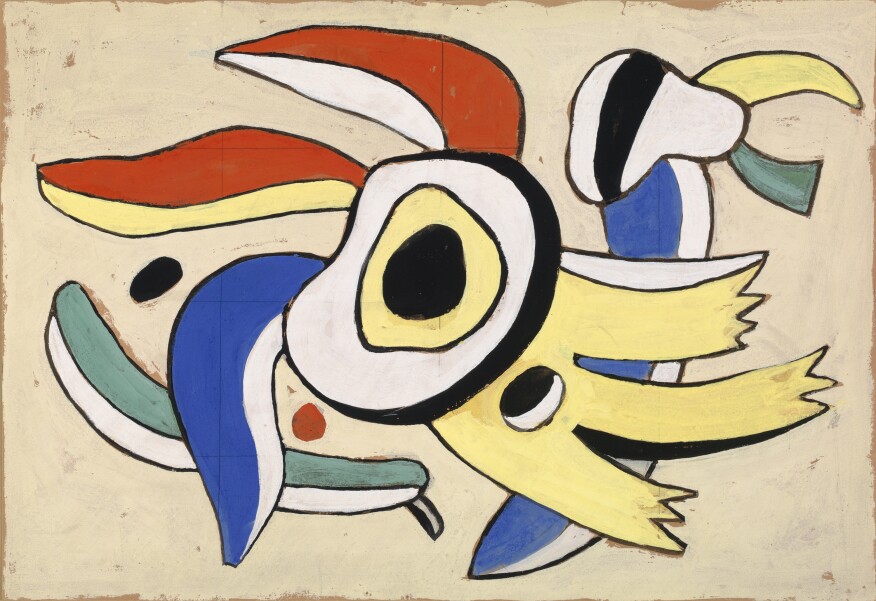

In current dialogues, Aalto’s individual stature is so significant that it is easy to forget how deeply others influenced his work. The Ateneum show reinforces the value of one’s collaborators and networks for developing an enlightened design trajectory. For example, Aalto was closely associated with the artists Hans (Jean) Arp, Alexander Calder, Fernand Léger, and László Moholy-Nagy, whose works are on display in "Art and the Modern Form." These and other colleagues played an important role as both professional collaborators and friends. Not only did they support one another’s career development, but they also regularly traveled and dined together, formulating shared philosophies concerning art and design. Seen in juxtaposition, these artists’ visual languages are readily apparent in Aalto’s own approaches.

Aalto’s most important—and underappreciated—colleague was Aino Marsio-Aalto, his wife and professional partner. Alvar and Aino were such close collaborators that it is impossible to determine each individual’s specific contributions to the work. The couple married and began their career partnership in 1924, and together oversaw the completion of significant projects like the Paimio Sanatorium and co-founded the furniture company Artek, which still sells their internationally acclaimed furniture. Were it not for Aino’s untimely death from cancer in 1949, we would now likely privilege the couple over the individual and consider the Aaltos the Charles and Ray Eames of their day.

"Art and the Modern Form" also reinforces the role of experimentation in architecture. The Aaltos not only investigated new materials and manufacturing techniques as a regular practice but also frequently worked outside the bounds of the architectural discipline. Many of the glass vessels, lighting fixtures, and furniture they designed in the 1930s and beyond have become some of the most recognizable objects of modern design, and are still in mass production today. Notable examples include Alvar Aalto’s sculptural Savoy Vase of 1936 and Aino Marsio-Aalto’s Bölgeblick series of pressed glass objects. The exhibition also includes a video documentary of Alvar Aalto’s famous Stool 60, whose L-shaped legs required the development of new wood-bending techniques in 1933.

In addition to the design of furnishings, the Aaltos also experimented in other non-architectural disciplines. Aino was skilled at interior design and photography; Alvar explored painting and sculpture. His experimental wood reliefs reside somewhere between sculpture and material research, art and science. These works’ eye-catching, sinuous forms and refined craftsmanship suggest that they are finished sculptural objects—yet they are equally as important as indicators of a process, as Alvar used them as tools to explore material behaviors for future designs. In today’s practice, it is highly unusual for architects to operate similarly to the Aaltos, crossing disciplinary boundaries as boldly as they did; yet their formidable design legacy reinforces the significant benefits such an approach.

Most profoundly, the Ateneum exhibition reminds us of the Aaltos’ elevated sense of purpose. With the Russian Revolution of 1917, Finland won its independence after centuries of occupation by Russia and Sweden. At the same time, rapid urbanization and industrialization brought swift changes—and significant social challenges—to the country, which became mired in a civil war in 1918. With the beginning of their partnership in 1924, Alvar and Aino Aalto envisioned contributing to the establishment of a new design identity for Finland. Their architecture practice comprised only one part of their many activities, which included curating exhibitions of Finnish as well as international art via their Artek gallery. Their own widely published home, which they designed and furnished, also symbolized a new modern approach to domesticity. “At the time, the key concern for the Aaltos was to develop a new, modern form of habitation,” describes art historian Renja Suominen-Kokkonen. “This was not limited to architecture; the idea was to invent an entirely new way of living.”

By comparison, today’s architects are largely unconcerned with design’s role in the context of a newly formed nation or a rapidly changing society. But have we lost the sense of purpose that comes with these kinds of higher calling? Obviously, we face many of our own challenges today, and contemporary problems like global warming and social inequity necessitate a passionate pursuit of solutions. Yet these stark, overwhelming realities have cast long shadows over the creative disciplines. "Alvar Aalto: Art and the Modern Form" provides much-needed inspiration, reminding us of the positive outlook and creative capacities of the Aaltos, who never ceased to be collaborative, curious, and visionary within their own tumultuous time.